2008 marks the 50th anniversary of the formation of the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD). On 12 May 1958, Canada and the United States signed a pact to jointly defend the skies of North America against Soviet bombers. While it’s difficult to believe now, during the darkest days of the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, as part of those NORAD defenses, many communities in the United States had their own neighborhood missile batteries, where nuclear-tipped missiles sat at constant alert, ready to shoot down waves of Soviet bombers. Few people now can remember the almost visceral fear Americans had of Soviet bombers coming over the North Pole with no notice to drop atomic bombs on our cities, turning them into radioactive rubble.

One of those neighborhood fire control sites and the magazine for its missiles is still visible on the east side of Waukesha, Wisconsin. The fire control (FC) site at the city’s Hillcrest Park is one of the best preserved in the United States, with original buildings and the pedestals for the radars still standing.

The first line—an “area defense”

In the Upper Midwest, NORAD operated two lines of defense to protect the heavy industrial cities in the heartland such as Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, and the Gary, Indiana, and Cleveland, Ohio, steel mills. The first line of defense was an “area defense” of long-range radars to detect the bombers and guide jet fighters to shoot them down well to the north. Remnants of that area defense remain at Volk Field Air National Guard Base (ANGB) in Camp Douglas, Wisconsin; Dane County Regional Airport—Truax Field at Madison, and Duluth International Airport in Duluth, Minnesota. At all three bases, jet fighter interceptors sat alert ready to scramble into the air with as little as five minutes notice.

To detect, control, and guide those jet fighters to its targets, the Air Force operated radar stations at Osceola, Antigo, and Williams Bay that fed data to the NORAD defenses, and into the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) system at Madison’s Truax Field. The Truax SAGE was the command post for NORAD’s Chicago Air Defense Sector and integrated all remote radar data and set priorities for intercepts. Those who lived in or visited Madison in the 1960s may remember the huge windowless square white building on the east side of the runway at what was then called Truax Air Force Base.

The second line—a “point” defense

The second line of defense was a “point defense” offering a last chance to shoot down bombers that might have slipped past the jet fighters. In 1955, the Air Force began planning for an interceptor base in Kenosha County. The base was to be named for Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame inductee Richard I. Bong and was intended to be home to a wing of 72 jet interceptors to defend Milwaukee and Chicago. Construction of Bong AFB began in 1958. Then in 1959, only days before crews were to start pouring the concrete for the 13,000-foot runway, the Secretary of the Air Force stopped construction and ordered the base abandoned. The primary reason construction stopped was that the Army’s Nike missile system proved it could provide the point defense against Soviet bombers that might leak through the interceptor screen, and those missiles were then being deployed around major industrial cities and defense installations nationwide.

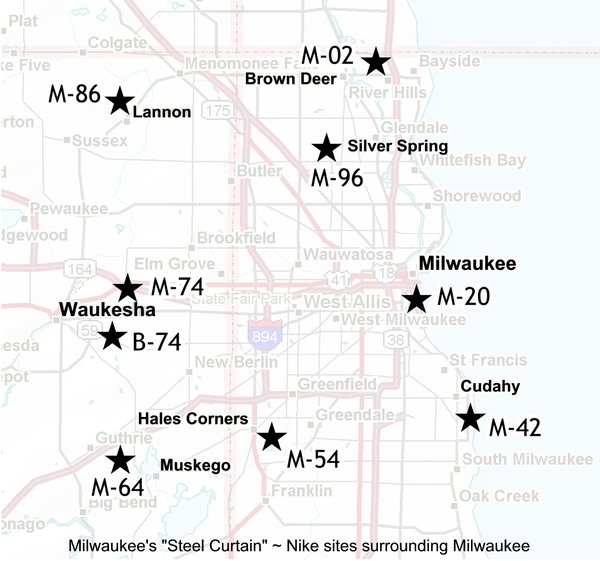

In Wisconsin, Milwaukee received a ring of eight Nike launch sites to protect the city; all controlled from the fire control site at Waukesha. The missile magazines and launch sites were at Brown Deer, on the lakeshore at what is now Summerfest Park in Milwaukee; Silver Spring, Cudahy, Hales Corners, Muskego, Lannon, and Waukesha. The Army designated the site at Waukesha as M-74, where high-power acquisition radar (HIPAR), missile tracking radar (MTR), and a remote radar integration system (RRIS) were based. The pedestals that held the HIPAR and MTR still stand at Waukesha’s Hillcrest Park, as well as the Integrated Fire Control (IFC) building.

The Nike antiaircraft missile

The U.S. Army operated two types of Nike missiles in Wisconsin. The first was the short-range (30 miles) Nike-Ajax armed with a conventional high-explosive warhead. The second was the longer range (70 miles) Nike-Hercules that could carry either a conventional or a nuclear warhead. When loaded with the nuclear warhead, the Hercules would have exploded in the middle of a bomber formation, knocking many aircraft out of the sky at once.

The W-31 nuclear warhead on the Hercules had two possible yields: 2 kilotons (Kt) or 40 Kt. It could well be that during the Cold War, no one much considered the collateral damage the nuclear warhead of the Hercules would have caused if it had been used. A Nike-Hercules launched from Milwaukee towards the west would have been just about over Madison at its max range of 70 miles. A 40 Kt nuclear warhead (more than twice the yield of the Hiroshima bomb) exploding over Madison at 30,000 to 40,000 feet would have caused as much damage as the Soviet bombers the warhead was meant to destroy.

Air defense units in Wisconsin never fired any missiles from the neighborhood sites around Milwaukee, but the Army randomly selected launch crews and sent them to White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico for live firings to evaluate their readiness and the performance of the missiles. Those were called SNAP launches—short notice annual practice.

If You Go: The Waukesha Nike Sites

The M-74 fire control site is located at what is now Hillcrest Park on Waukesha’s east side. Hillcrest Park is just off Davidson Road, open to the public, and easy to find—it’s on the highest hill in the area. The Army placed Site M-74 on the hill because it offered an excellent view of the horizon and the sky to the north and west. If you visit the site, the pedestals that held the HIPAR and MTR antennas will be immediately obvious. They are in good shape, although why they are there and the purpose must surely be a mystery to the uninformed. You can also see two intact buildings still standing. The building closest to the radar pedestals is windowless; it housed the IFC. The building near the parking lot was an administrative/storage building. Both are standard 1950s-era military concrete block construction with flat roofs.

The most obvious feature at Hillcrest Park is a municipal water tank that looks as though it might have been part of Nike site. Actually, the water tank is unrelated to M-74. The tank is a large circular concrete reservoir much like a swimming pool, but with a concrete cap to keep out people and contaminants. The concrete water storage tank shows up very well in aerial photos of the site, or if you fly over it.

At Hillcrest Park, you can also see the plaque that veterans who served at M-74 placed there in 1988 during a reunion. In 2005, the sons of U-2 spy plane pilot Francis Gary Powers and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev made a joint visit to Hillcrest Park to declare the Cold War as officially over. Since Site M-72 [sic] is one the best preserved Nike sites in the United States, there has been talk of turning the site into a Cold War museum, although that idea has gained little momentum.

The Waukesha missile magazine and launch site is about one mile south of M-74 off West Cleveland Avenue. There is little left to see at this site, which the Army called Battery 74. A crumbling asphalt road leads up the hill to where the Nike-Ajax and Nike-Hercules missiles were kept in underground magazines, and a locked gate next to a well-weathered plywood guardhouse blocks vehicle access. All evidence of the missile magazines is gone, although there is still a broad expanse of broken and eroded concrete where missile unloading and loading took place.

The status of the site—now called Missile Park—remains in question. The National Park Service controls the site and would like to give it to the City of Waukesha at no cost, but the site remains contaminated. There are questions of who will pay for the cleanup, and who will be responsible for future problems that might surface. If there is an agreement on site clean up and liability, the 24-acre Missile Park will be a fine addition to Waukesha’s park system. The site is covered by thick vegetation and would like be ideal for hiking and biking trails and picnic areas.

Probably few people today realize that during the Cold War, NORAD actually based nuclear-tipped missiles in Wisconsin neighborhoods. It’s probably also ironic that an equally small number of people at the time even realized those nuclear missiles were there, constantly ready to be launched so they could explode high in the sky above Wisconsin.