Forward in Flight - Fall 2021

Volume 19, Issue 3 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Fall 2021 Photos from 2021 EAA’s Oshkosh AirVenture

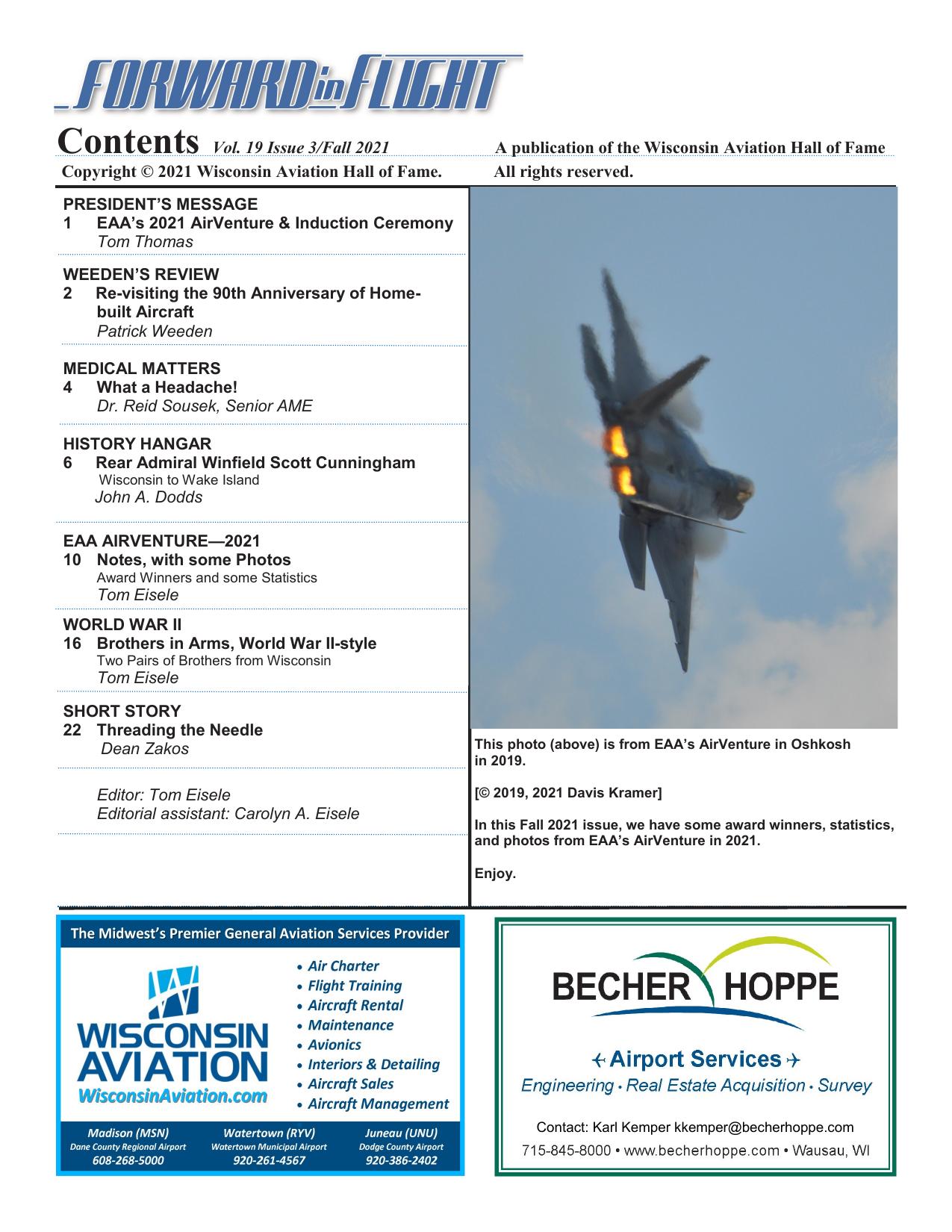

Contents Vol. 19 Issue 3/Fall 2021 Copyright © 2021 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All rights reserved. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 1 EAA’s 2021 AirVenture & Induction Ceremony Tom Thomas WEEDEN’S REVIEW 2 Re-visiting the 90th Anniversary of Homebuilt Aircraft Patrick Weeden MEDICAL MATTERS 4 What a Headache! Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME HISTORY HANGAR 6 Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Cunningham Wisconsin to Wake Island John A. Dodds EAA AIRVENTURE—2021 10 Notes, with some Photos Award Winners and some Statistics Tom Eisele WORLD WAR II 16 Brothers in Arms, World War II-style Two Pairs of Brothers from Wisconsin Tom Eisele SHORT STORY 22 Threading the Needle Dean Zakos Editor: Tom Eisele Editorial assistant: Carolyn A. Eisele This photo (above) is from EAA’s AirVenture in Oshkosh in 2019. [© 2019, 2021 Davis Kramer] In this Fall 2021 issue, we have some award winners, statistics, and photos from EAA’s AirVenture in 2021. Enjoy. Contact: Karl Kemper kkemper@becherhoppe.com

President’s Message By Tom Thomas This summer we were lucky to once again have EAA AirVenture. During AirVenture, I worked as a volunteer “Government Host.” This job included both giving tours of the grounds and staffing a booth. For AirVenture, EAA took several proactive COVID measures. For example, when I was staffing the booth (which normally took two hours), we primarily found ourselves answering questions on MOSAIC (Modernization of Special Airworthiness Certification). Then, too, we dealt with other topics across the board. Interestingly, cleaning staff came by our table and wiped it (and pens and markers) with cleaning fluid every hour. Since the EAA AirVenture of 2019, some recently purchased land south of the Wittman runways has been developed for aircraft parking. Now, with the expanded parking, the AirVenture of 2021 was the first year in which Oshkosh Tower never had to divert aircraft to surrounding airports due to a lack of aircraft parking spaces. AirVenture 2021 was a good year and was the third time that event attendance exceeded 600,000 visitors. Highlights this year included U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command, and an impressive Salute to Humanitarian Aviation, as the ORBIS flying eye hospital and the Samaritan’s Purse DC-8 were on hand. It is truly amazing how aircraft can “take the hospital to the patients” basically anywhere in the world – wherever they are needed. Overall, 2021 was another outstanding AirVenture! * * * * Your WAHF Board is working on this year’s Induction ceremony scheduled for October 23rd at the EAA Museum in Oshkosh. The Induction invitations have been drafted and will be mailed soon. In discussions with EAA staff, we have requested moving the start time one hour earlier to 4:00 pm. However, the EAA museum is open to the public until 5:00 pm and they cannot change the closing time. Our normal time allotment for four Inductees is from 5:00 pm to 9:00 pm. With our expanded number of Inductees (combining the classes of 2020 and 2021), and with those Inductees attending now at six, EAA has granted us an additional hour, with a 10:00 pm closing time. Forward in Flight the only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s aviation events. Tom Eisele, editor W8863 U.S. Highway 12 Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-9762 513-484-0394 t.d.eisele@att.net A young boy dreams about his future in the sky at EAA’s 2021 AirVenture [© 2021 Tom Thomas] We’ll still aim to conclude our ceremony at 9:00 pm, but we now have an extra hour’s flexibility, if it is needed. Also, we are working on improving the ceremony process this year, using new techniques and technology. These innovations will help us to maximize our time. In other WAHF news, 2018 Inductee, Don Winkler, has just been presented with the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) 50 Year Service Award. I first met Don while I was actively working with the CAP Cadet Squadron at the Madison Airport in the mid-70s. Don’s son was a CAP Cadet. Don’s award reads: “Presented to Lt Col Donald P. Winkler, In Recognition of 50 Years of Outstanding Service to the Civil Air Patrol.” Congratulations, Don, on this well-deserved award! Lastly, we aren’t totally out of the woods with a new COVID variant “on the table.” We’ll be watching the progress on fighting the virus, while we continue with our plans for the Induction ceremony in October. In last year’s planning, and our subsequent discussions with EAA, there would have been a limit on the number of people allowed to attend. If that limitation on attendance were to come to pass, we’ll make adjustments for what is best for WAHF members. On the cover: B-24J of the 93rd Bomb Group, called “Full House,” flying out to sea from Sweden, marking the funeral service for Lt. John Harrington, mortally wounded on 8th AAF Mission 798 in January, 1945. The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit Story begins on page 16. membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those Photo digitally enhanced who made that history, inform others of it, and promote and courtesy of Ted and aviation education for future generations. Shelley Eisele.

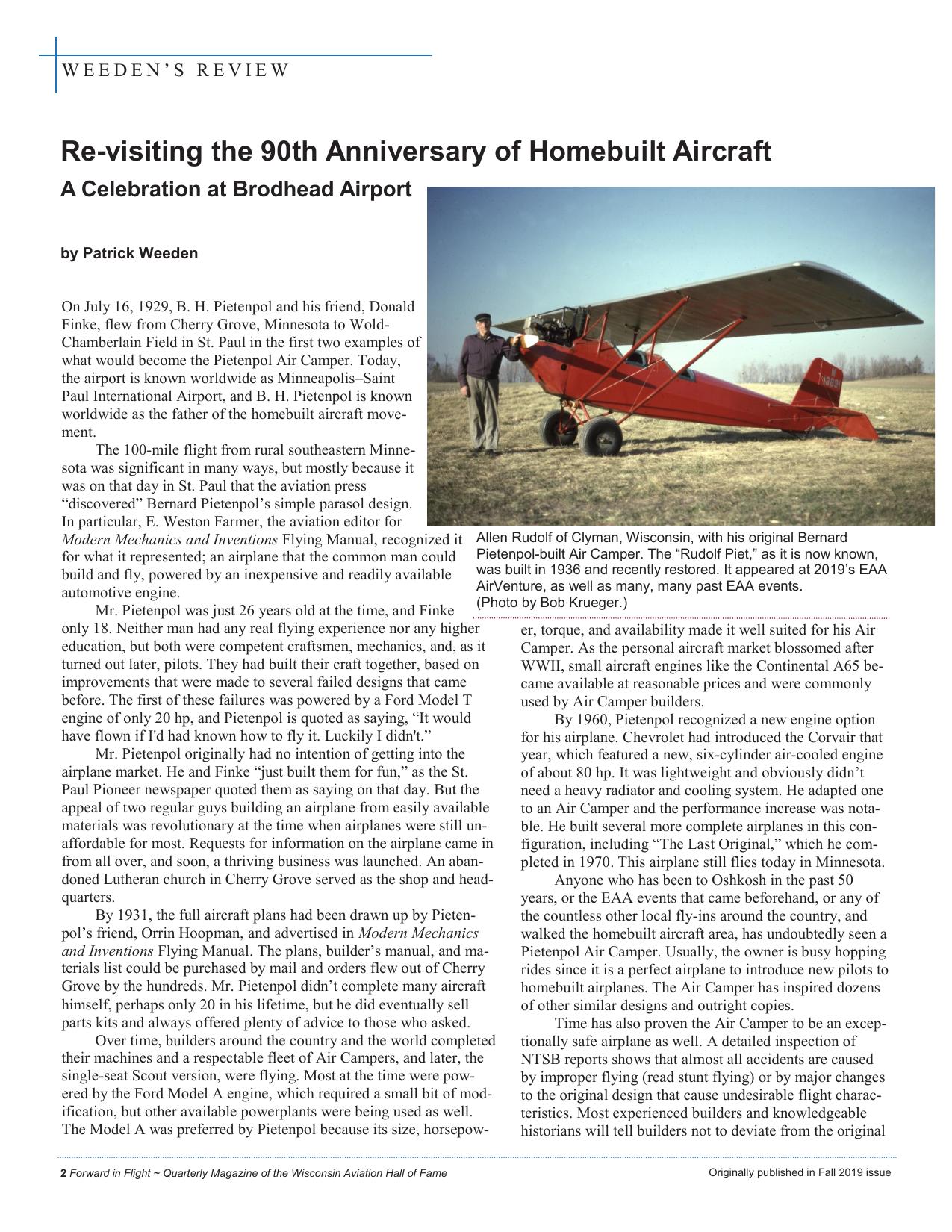

WEEDEN’S REVIEW Re-visiting the 90th Anniversary of Homebuilt Aircraft A Celebration at Brodhead Airport by Patrick Weeden On July 16, 1929, B. H. Pietenpol and his friend, Donald Finke, flew from Cherry Grove, Minnesota to WoldChamberlain Field in St. Paul in the first two examples of what would become the Pietenpol Air Camper. Today, the airport is known worldwide as Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport, and B. H. Pietenpol is known worldwide as the father of the homebuilt aircraft movement. The 100-mile flight from rural southeastern Minnesota was significant in many ways, but mostly because it was on that day in St. Paul that the aviation press “discovered” Bernard Pietenpol’s simple parasol design. In particular, E. Weston Farmer, the aviation editor for Modern Mechanics and Inventions Flying Manual, recognized it Allen Rudolf of Clyman, Wisconsin, with his original Bernard for what it represented; an airplane that the common man could Pietenpol-built Air Camper. The “Rudolf Piet,” as it is now known, was built in 1936 and recently restored. It appeared at 2019’s EAA build and fly, powered by an inexpensive and readily available AirVenture, as well as many, many past EAA events. automotive engine. (Photo by Bob Krueger.) Mr. Pietenpol was just 26 years old at the time, and Finke only 18. Neither man had any real flying experience nor any higher er, torque, and availability made it well suited for his Air education, but both were competent craftsmen, mechanics, and, as it Camper. As the personal aircraft market blossomed after turned out later, pilots. They had built their craft together, based on WWII, small aircraft engines like the Continental A65 beimprovements that were made to several failed designs that came came available at reasonable prices and were commonly before. The first of these failures was powered by a Ford Model T used by Air Camper builders. engine of only 20 hp, and Pietenpol is quoted as saying, “It would By 1960, Pietenpol recognized a new engine option have flown if I'd had known how to fly it. Luckily I didn't.” for his airplane. Chevrolet had introduced the Corvair that Mr. Pietenpol originally had no intention of getting into the year, which featured a new, six-cylinder air-cooled engine airplane market. He and Finke “just built them for fun,” as the St. of about 80 hp. It was lightweight and obviously didn’t Paul Pioneer newspaper quoted them as saying on that day. But the need a heavy radiator and cooling system. He adapted one appeal of two regular guys building an airplane from easily available to an Air Camper and the performance increase was notamaterials was revolutionary at the time when airplanes were still unble. He built several more complete airplanes in this conaffordable for most. Requests for information on the airplane came in figuration, including “The Last Original,” which he comfrom all over, and soon, a thriving business was launched. An abanpleted in 1970. This airplane still flies today in Minnesota. doned Lutheran church in Cherry Grove served as the shop and headAnyone who has been to Oshkosh in the past 50 quarters. years, or the EAA events that came beforehand, or any of By 1931, the full aircraft plans had been drawn up by Pietenthe countless other local fly-ins around the country, and pol’s friend, Orrin Hoopman, and advertised in Modern Mechanics walked the homebuilt aircraft area, has undoubtedly seen a and Inventions Flying Manual. The plans, builder’s manual, and maPietenpol Air Camper. Usually, the owner is busy hopping terials list could be purchased by mail and orders flew out of Cherry rides since it is a perfect airplane to introduce new pilots to Grove by the hundreds. Mr. Pietenpol didn’t complete many aircraft homebuilt airplanes. The Air Camper has inspired dozens himself, perhaps only 20 in his lifetime, but he did eventually sell of other similar designs and outright copies. parts kits and always offered plenty of advice to those who asked. Time has also proven the Air Camper to be an excepOver time, builders around the country and the world completed tionally safe airplane as well. A detailed inspection of their machines and a respectable fleet of Air Campers, and later, the NTSB reports shows that almost all accidents are caused single-seat Scout version, were flying. Most at the time were powby improper flying (read stunt flying) or by major changes ered by the Ford Model A engine, which required a small bit of modto the original design that cause undesirable flight characification, but other available powerplants were being used as well. teristics. Most experienced builders and knowledgeable The Model A was preferred by Pietenpol because its size, horsepowhistorians will tell builders not to deviate from the original 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Originally published in Fall 2019 issue

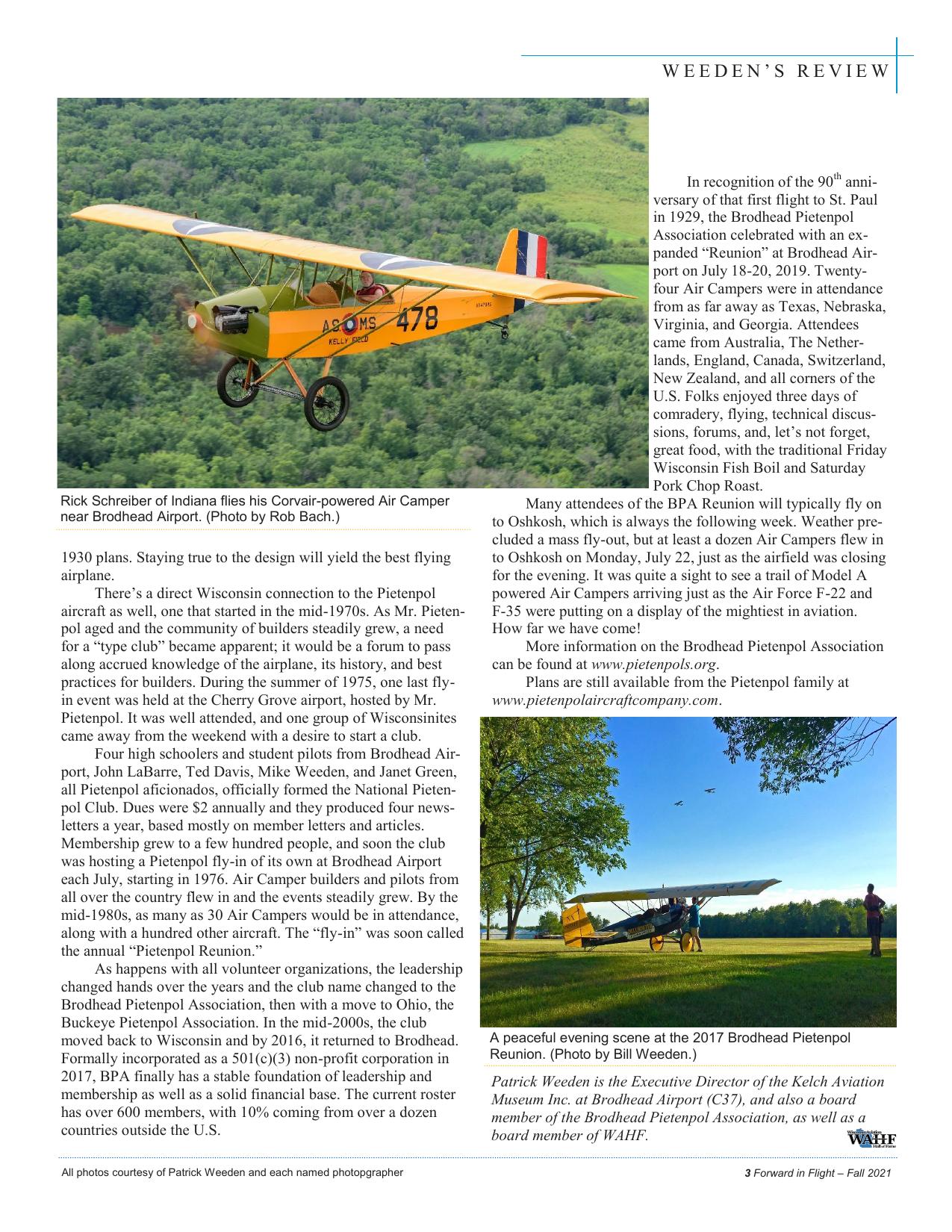

WEEDEN’S REVIEW Rick Schreiber of Indiana flies his Corvair-powered Air Camper near Brodhead Airport. (Photo by Rob Bach.) 1930 plans. Staying true to the design will yield the best flying airplane. There’s a direct Wisconsin connection to the Pietenpol aircraft as well, one that started in the mid-1970s. As Mr. Pietenpol aged and the community of builders steadily grew, a need for a “type club” became apparent; it would be a forum to pass along accrued knowledge of the airplane, its history, and best practices for builders. During the summer of 1975, one last flyin event was held at the Cherry Grove airport, hosted by Mr. Pietenpol. It was well attended, and one group of Wisconsinites came away from the weekend with a desire to start a club. Four high schoolers and student pilots from Brodhead Airport, John LaBarre, Ted Davis, Mike Weeden, and Janet Green, all Pietenpol aficionados, officially formed the National Pietenpol Club. Dues were $2 annually and they produced four newsletters a year, based mostly on member letters and articles. Membership grew to a few hundred people, and soon the club was hosting a Pietenpol fly-in of its own at Brodhead Airport each July, starting in 1976. Air Camper builders and pilots from all over the country flew in and the events steadily grew. By the mid-1980s, as many as 30 Air Campers would be in attendance, along with a hundred other aircraft. The “fly-in” was soon called the annual “Pietenpol Reunion.” As happens with all volunteer organizations, the leadership changed hands over the years and the club name changed to the Brodhead Pietenpol Association, then with a move to Ohio, the Buckeye Pietenpol Association. In the mid-2000s, the club moved back to Wisconsin and by 2016, it returned to Brodhead. Formally incorporated as a 501(c)(3) non-profit corporation in 2017, BPA finally has a stable foundation of leadership and membership as well as a solid financial base. The current roster has over 600 members, with 10% coming from over a dozen countries outside the U.S. All photos courtesy of Patrick Weeden and each named photopgrapher In recognition of the 90th anniversary of that first flight to St. Paul in 1929, the Brodhead Pietenpol Association celebrated with an expanded “Reunion” at Brodhead Airport on July 18-20, 2019. Twentyfour Air Campers were in attendance from as far away as Texas, Nebraska, Virginia, and Georgia. Attendees came from Australia, The Netherlands, England, Canada, Switzerland, New Zealand, and all corners of the U.S. Folks enjoyed three days of comradery, flying, technical discussions, forums, and, let’s not forget, great food, with the traditional Friday Wisconsin Fish Boil and Saturday Pork Chop Roast. Many attendees of the BPA Reunion will typically fly on to Oshkosh, which is always the following week. Weather precluded a mass fly-out, but at least a dozen Air Campers flew in to Oshkosh on Monday, July 22, just as the airfield was closing for the evening. It was quite a sight to see a trail of Model A powered Air Campers arriving just as the Air Force F-22 and F-35 were putting on a display of the mightiest in aviation. How far we have come! More information on the Brodhead Pietenpol Association can be found at www.pietenpols.org. Plans are still available from the Pietenpol family at www.pietenpolaircraftcompany.com. A peaceful evening scene at the 2017 Brodhead Pietenpol Reunion. (Photo by Bill Weeden.) Patrick Weeden is the Executive Director of the Kelch Aviation Museum Inc. at Brodhead Airport (C37), and also a board member of the Brodhead Pietenpol Association, as well as a board member of WAHF. 3 Forward in Flight – Fall 2021

MEDICAL MATTERS What a Headache! By Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME With my last two articles discussing the FAA 8500-8 form and medical application process, some may think this title is about another bureaucratic topic. Instead, we will get back to an actual medical topic, headaches. Headaches might seem ordinary, but, they may actually represent a symptom of another condition or diagnosis. In my role as an Urgent Care Physician, a headache is a very common chief complaint. Based on CDC data from a recent National Health Interview Survey, roughly 10% of men 18 or older, and 20% of women 18 or over, have reported a “severe headache” or “migraine” in the past 3 months. Another survey (National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 1992-2001) found that headaches accounted for 2.1 million Emergency Department (ED) visits per year, nearly 2.2% of such visits. As a point of reference, other common complaints (such as abdominal pain or chest pain) each account for 4-5% of all ED visits per year. Not all headaches are created equally. 90% of headaches fall into one of three groups: migraine, tension-type, and cluster headaches. The most common of these would be the tension headache. The most acutely disabling type is likely cluster headache, although many migraine sufferers would likely argue otherwise. Migraine headaches Individuals with migraine headaches generally experience recurrent attacks. These headaches develop over a time frame of hours or days. Many migraines proceed through 4 phases: prodrome, aura, headache, postdrome. The prodrome occurs 24-48 hours prior to the onset of the headache and may occur in over 75% of migraine sufferers (Cephalalgia. 2016 Sep;36(10):951-9). A broad spectrum of symptoms may be experienced in this phase, including, but not limited to, appetite changes, concentration difficulties, cold extremities, diarrhea, irritability, weakness, yawning, and stretching. Then, 25% of sufferers will experience a migraine aura. This may occur with or without symptoms of the headache itself. These develop over the course of an hour. Visual symptoms (such as bright lines or shapes) are commonly reported. Other symptoms including auditory symptoms (such as tinnitus or noises) may also be reported. Some may experience burning/tingling sensations, or even motor symptoms, such as jerking or repetitive jerking movements. While the previous all represent “positive” symptoms, it is possible to have “negative” symptoms such as loss of vision, hearing, or motor/sensory loss to certain parts of the body. The migraine headache itself often affects only one side of the head. Many experience a pulsing or throbbing pain that increases over a few hours and might last days, with many people experienc4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ing light or sound sensitivity. Sleep may improve symptoms. Unfortunately, patients often experience nausea and vomiting. The postdrome follows the throbbing headache. Patients often feel exhausted; however, some may feel excited or euphoric. A study of 1200+ patients (Cephalalgia. 2007;27 (5):394) found that three-quarters of migraine sufferers reported triggers for their migraines. 80% of sufferers attributed development of a migraine to stress. 65% of women found menstrual cycle/hormones to blame. Other common causes included skipping meals, poor sleep, strong odors/perfumes, neck pain, and alcohol. Treatment for migraines can consist of abortive therapy (once headache has already started) or preventive or prophylactic therapy. Common abortive treatments for migraines include NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen or naproxen), Tylenol (acetaminophen), or triptans (such as sumatriptan or Imitrex). Many patients experience significant nausea with migraines, so use of anti-nausea meds is common. Even with anti-nausea medications, however, some patients cannot tolerate abortive therapy in oral form. Therefore, the above classes of medication are often also available with other delivery mechanisms. For example, an intramuscular (injection) form of an NSAID is ketorolac or Toradol. Similarly, there are injectable forms of triptan medications and even nasal spray triptan formulations. The diagnostic criteria for a migraine are outlined in the ICHD-3 (International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition). In my experience in the Urgent Care setting, some patients present with a chief complaint of a “migraine,” yet they do not have a true migraine. Many patients will use the word “migraine” interchangeably with “headache.” These “migraines” that are not true migraines often represent tension-type headaches. Tension-type headaches Tension-type headaches are the most common type of headache and nearly 80% of individuals will experience one in any given year. Tension-type headaches are often reported as a “tight cap” or “band-like” and are bilateral and throbbing. Many patients report discomfort to the neck muscles. For most, treatment with an over the counter medication such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen is adequate. Those who do not respond to the over the counter options are often prescribed medications to prevent headaches.

MEDICAL MATTERS A long list of different classes of medications have been tried. However, a common theme in medicine is that, when multiple, different therapeutic classes are available, usually none stands out as a clear leader. Modest improvement (or even no improvement above placebo) is reported in some of these research studies. It often turns out to be a trial and error approach to find what works for the individual. My practice style is to treat the patient in front of me and not the research study. So, I use what works in the individual, even if a study claims no benefit--as long as there is not a risk or harm to the patient. Some patients are treated with non-medication approaches, such as biofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, or physical therapy. Again, though, there is no clear modality that stands out above the others; what works for you may not work for me. Cluster headaches The third major headache type is cluster headaches. Cluster headaches are often severe orbital or temporal pain affecting one side of the head. These are often short duration and can occur multiple times per day. They may be associated with actual physical findings, such as eye redness or tearing, nasal congestion or runny nose, sweating, pupil constriction or dilation. These physical symptoms occur on the same side as the headache. As with the other headache types, treatment is divided into abortive therapy and prophylactic therapy. The initial abortive therapy is oxygen. Some studies have shown that up to 80% of patients respond to oxygen therapy. For those that do not respond, a triptan medication is often tried. Preventive therapy mainly consists of a calcium channel blocker such as verapamil or steroids. Aeromedical implications Question 18a on the form 8500-8 asks the applicant about a medical history of Frequent or Severe Headaches. Similarly, item 46 requires the AME to consider any neurologic condition, including headaches. The FAA’s concern would be whether the headache would be incapacitating, along with whether the treatment would impact the pilot’s ability to function. As discussed above, there are numerous medications tried for prevention of headaches. One common side effect of many of these is sedation and altered alertness. Clearly certification is not allowed with a medication that would affect a pilot’s alertness. However, there are pilots who are able to be certified with headaches. While the published data that I was able to find are a few years old, in 2006, there were about 900 firstclass airmen, 1,000 second-class airmen, and 2,700 thirdclass airmen on Special Issuance for Migraines. Medical Certification - Special Issuance When seeking a Special Issuance, the applicant must provide medical records. In most cases, an evaluation from a Neurologist or the treating physician is required. This report should include the characteristic symptoms, frequency, severity, and treatment plan. The treatment plan should document if any medications are used and if there are any side effects. This documentation should also clearly state the presence (or absence) of any neurologic symptoms. If this information is favorably reviewed, the FAA may then grant a Special Issuance (SI) or AME Assisted Special Issuance (AASI). The SI or AASI specification letter will state what records need to be submitted at future examinations to continue certification. Medical Certification - CACI In 2015, the FAA released the headache CACI worksheet. CACI stands for “Conditions AMEs Can Issue.” This protocol sits between regular issuance and special issuance, as it does require all the documentation or further evaluation of the SI/AASI, yet the AME makes the determination for issuance if all criteria are met. The first CACI criterion to be met is that the treating physician finds the airman’s condition to be stable. The next criterion is the type of headache. Common migraines, tension headaches, and cluster headaches are acceptable, while Ocular Migraines and complicated migraines are not acceptable. The frequency of headaches must be less than one per month to meet CACI criteria. There must have been no episodes requiring hospitalization and no more than 2 outpatient treatments for exacerbations. Above, we discussed the preventive treatment options and their associated side effects. There are two options that are certifiable in the CACI program, calcium channel blockers or beta blockers. Over the counter medications (such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen) are acceptable; but a combo OTC medication may contain sedating ingredients, so it is important to read labels. Certain prescription abortive therapies (such as a triptan or nausea medication) may be used. However, a no-fly wait time may apply. For triptan medications, it is generally 24 hours no-fly. For promethazine (antinausea medication), this no-fly time is 96 hours. As we have discussed in other articles, most medical conditions can be certified, as long as they are stable and not likely to cause incapacitation, either sudden or subtle. In the case of headaches, there is a huge variation in symptomatology. For some, the headache may be more of a nuisance and not impact one’s ability to safely operate an airplane. For others, a headache may have neurologic symptoms that mimic a stroke and may cause significant disability. It is not possible to make a blanket statement on the medical certification of headaches. Each case is different. First, get your condition controlled and stable. Then, discuss your situation with your AME. If needed, your AME will help you to obtain the proper records to submit to the FAA and, ultimately, to obtain medical certification. [Dr. Reid Sousek is an FAA-designated Senior Aviation Medical Examiner, with offices near Oshkosh and Menasha.] 5 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

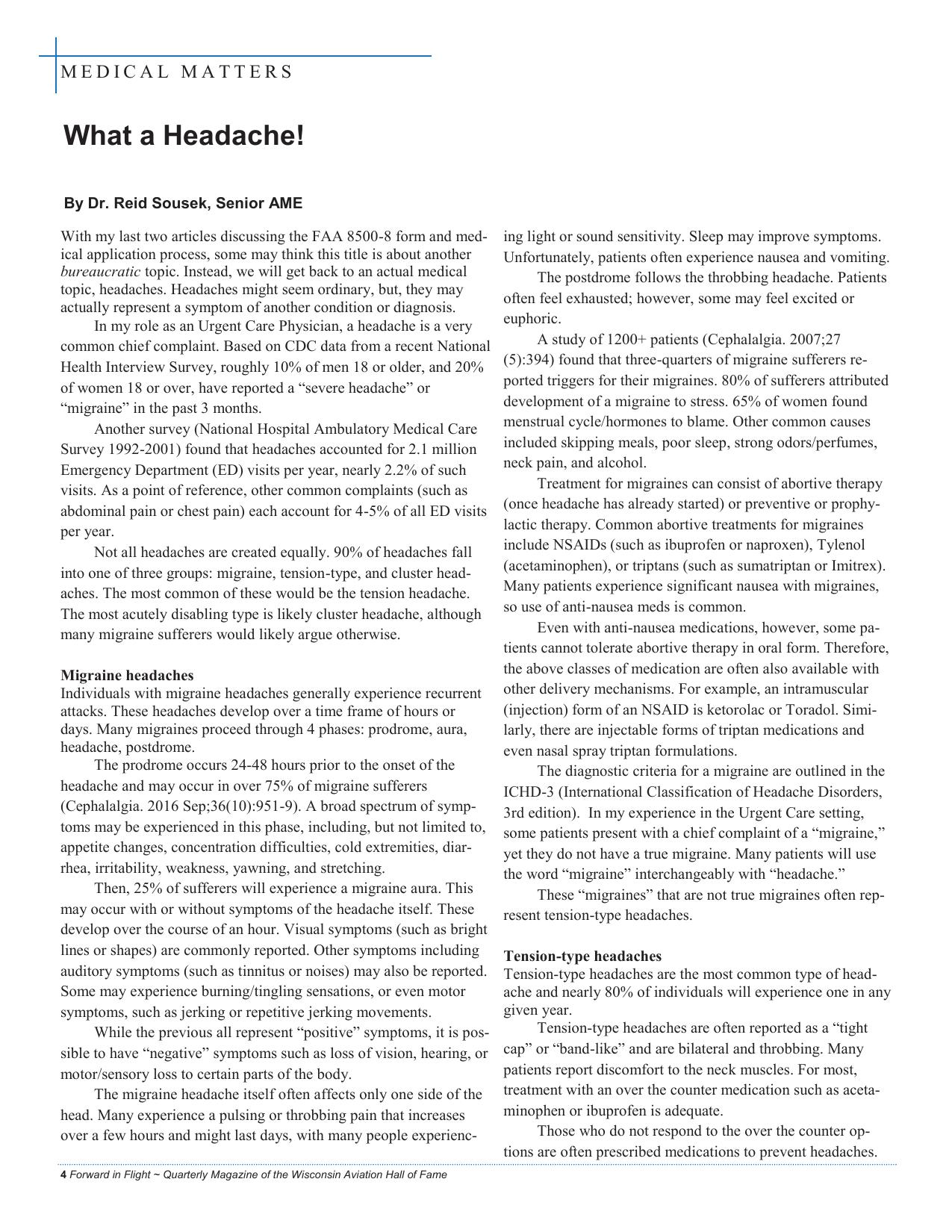

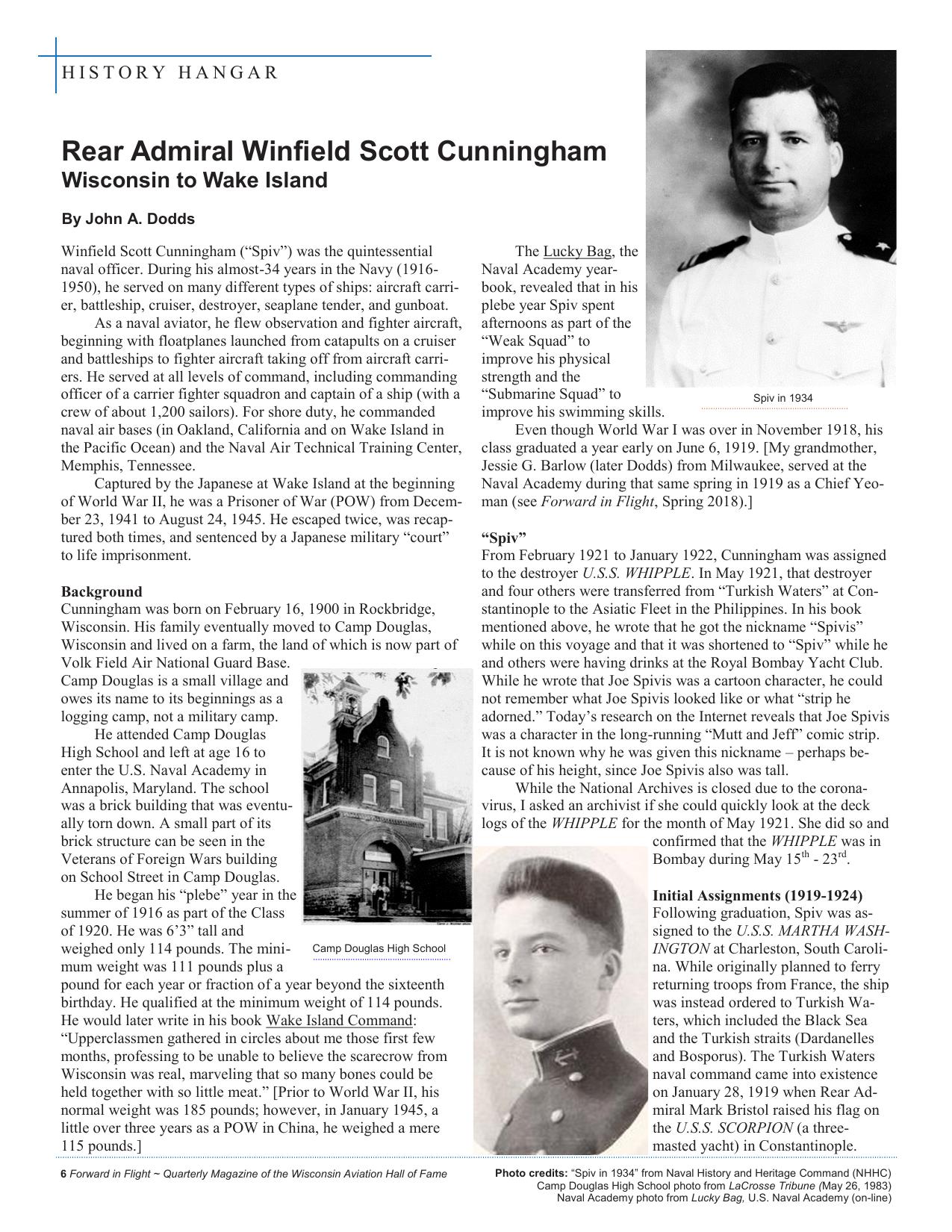

HISTORY HANGAR Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Cunningham Wisconsin to Wake Island By John A. Dodds Winfield Scott Cunningham (“Spiv”) was the quintessential naval officer. During his almost-34 years in the Navy (19161950), he served on many different types of ships: aircraft carrier, battleship, cruiser, destroyer, seaplane tender, and gunboat. As a naval aviator, he flew observation and fighter aircraft, beginning with floatplanes launched from catapults on a cruiser and battleships to fighter aircraft taking off from aircraft carriers. He served at all levels of command, including commanding officer of a carrier fighter squadron and captain of a ship (with a crew of about 1,200 sailors). For shore duty, he commanded naval air bases (in Oakland, California and on Wake Island in the Pacific Ocean) and the Naval Air Technical Training Center, Memphis, Tennessee. Captured by the Japanese at Wake Island at the beginning of World War II, he was a Prisoner of War (POW) from December 23, 1941 to August 24, 1945. He escaped twice, was recaptured both times, and sentenced by a Japanese military “court” to life imprisonment. Background Cunningham was born on February 16, 1900 in Rockbridge, Wisconsin. His family eventually moved to Camp Douglas, Wisconsin and lived on a farm, the land of which is now part of Volk Field Air National Guard Base. Camp Douglas is a small village and owes its name to its beginnings as a logging camp, not a military camp. He attended Camp Douglas High School and left at age 16 to enter the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The school was a brick building that was eventually torn down. A small part of its brick structure can be seen in the Veterans of Foreign Wars building on School Street in Camp Douglas. He began his “plebe” year in the summer of 1916 as part of the Class of 1920. He was 6’3” tall and weighed only 114 pounds. The mini- Camp Douglas High School mum weight was 111 pounds plus a pound for each year or fraction of a year beyond the sixteenth birthday. He qualified at the minimum weight of 114 pounds. He would later write in his book Wake Island Command: “Upperclassmen gathered in circles about me those first few months, professing to be unable to believe the scarecrow from Wisconsin was real, marveling that so many bones could be held together with so little meat.” [Prior to World War II, his normal weight was 185 pounds; however, in January 1945, a little over three years as a POW in China, he weighed a mere 115 pounds.] 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame The Lucky Bag, the Naval Academy yearbook, revealed that in his plebe year Spiv spent afternoons as part of the “Weak Squad” to improve his physical strength and the “Submarine Squad” to Spiv in 1934 improve his swimming skills. Even though World War I was over in November 1918, his class graduated a year early on June 6, 1919. [My grandmother, Jessie G. Barlow (later Dodds) from Milwaukee, served at the Naval Academy during that same spring in 1919 as a Chief Yeoman (see Forward in Flight, Spring 2018).] “Spiv” From February 1921 to January 1922, Cunningham was assigned to the destroyer U.S.S. WHIPPLE. In May 1921, that destroyer and four others were transferred from “Turkish Waters” at Constantinople to the Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines. In his book mentioned above, he wrote that he got the nickname “Spivis” while on this voyage and that it was shortened to “Spiv” while he and others were having drinks at the Royal Bombay Yacht Club. While he wrote that Joe Spivis was a cartoon character, he could not remember what Joe Spivis looked like or what “strip he adorned.” Today’s research on the Internet reveals that Joe Spivis was a character in the long-running “Mutt and Jeff” comic strip. It is not known why he was given this nickname – perhaps because of his height, since Joe Spivis also was tall. While the National Archives is closed due to the coronavirus, I asked an archivist if she could quickly look at the deck logs of the WHIPPLE for the month of May 1921. She did so and confirmed that the WHIPPLE was in Bombay during May 15th - 23rd. Initial Assignments (1919-1924) Following graduation, Spiv was assigned to the U.S.S. MARTHA WASHINGTON at Charleston, South Carolina. While originally planned to ferry returning troops from France, the ship was instead ordered to Turkish Waters, which included the Black Sea and the Turkish straits (Dardanelles and Bosporus). The Turkish Waters naval command came into existence on January 28, 1919 when Rear Admiral Mark Bristol raised his flag on the U.S.S. SCORPION (a threemasted yacht) in Constantinople. Photo credits: “Spiv in 1934” from Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) Camp Douglas High School photo from LaCrosse Tribune (May 26, 1983) Naval Academy photo from Lucky Bag, U.S. Naval Academy (on-line)

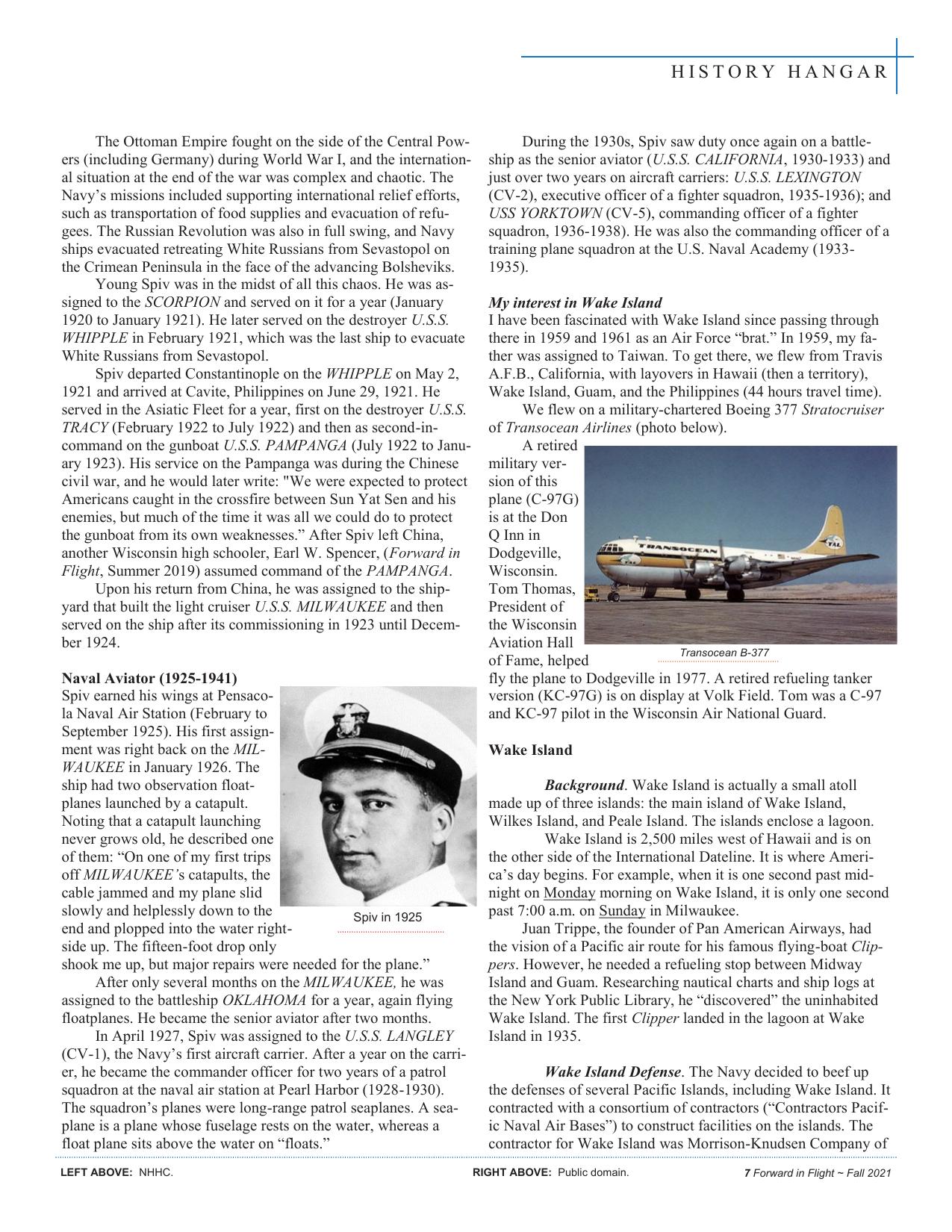

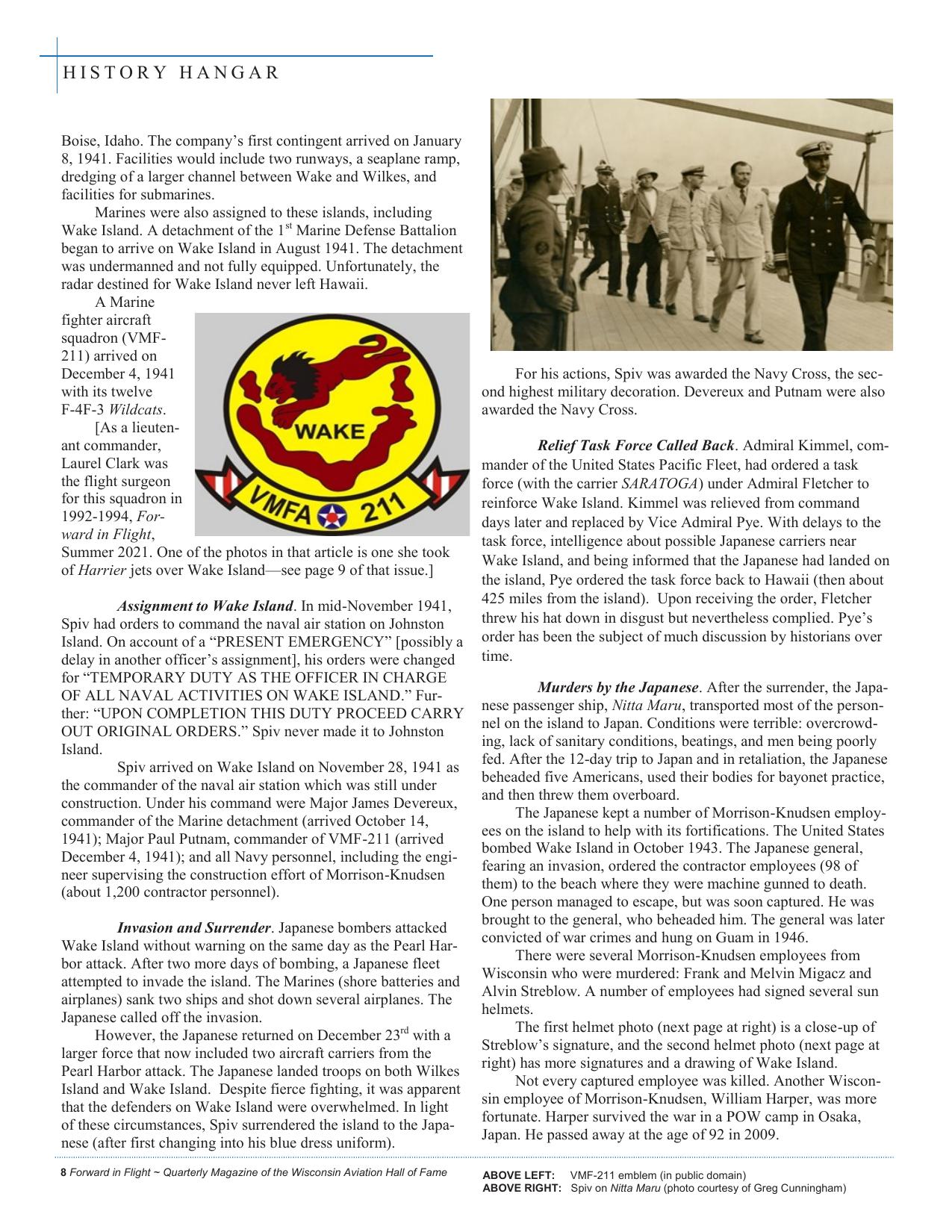

HISTORY HANGAR The Ottoman Empire fought on the side of the Central Powers (including Germany) during World War I, and the international situation at the end of the war was complex and chaotic. The Navy’s missions included supporting international relief efforts, such as transportation of food supplies and evacuation of refugees. The Russian Revolution was also in full swing, and Navy ships evacuated retreating White Russians from Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula in the face of the advancing Bolsheviks. Young Spiv was in the midst of all this chaos. He was assigned to the SCORPION and served on it for a year (January 1920 to January 1921). He later served on the destroyer U.S.S. WHIPPLE in February 1921, which was the last ship to evacuate White Russians from Sevastopol. Spiv departed Constantinople on the WHIPPLE on May 2, 1921 and arrived at Cavite, Philippines on June 29, 1921. He served in the Asiatic Fleet for a year, first on the destroyer U.S.S. TRACY (February 1922 to July 1922) and then as second-incommand on the gunboat U.S.S. PAMPANGA (July 1922 to January 1923). His service on the Pampanga was during the Chinese civil war, and he would later write: "We were expected to protect Americans caught in the crossfire between Sun Yat Sen and his enemies, but much of the time it was all we could do to protect the gunboat from its own weaknesses.” After Spiv left China, another Wisconsin high schooler, Earl W. Spencer, (Forward in Flight, Summer 2019) assumed command of the PAMPANGA. Upon his return from China, he was assigned to the shipyard that built the light cruiser U.S.S. MILWAUKEE and then served on the ship after its commissioning in 1923 until December 1924. Naval Aviator (1925-1941) Spiv earned his wings at Pensacola Naval Air Station (February to September 1925). His first assignment was right back on the MILWAUKEE in January 1926. The ship had two observation floatplanes launched by a catapult. Noting that a catapult launching never grows old, he described one of them: “On one of my first trips off MILWAUKEE’s catapults, the cable jammed and my plane slid slowly and helplessly down to the Spiv in 1925 end and plopped into the water rightside up. The fifteen-foot drop only shook me up, but major repairs were needed for the plane.” After only several months on the MILWAUKEE, he was assigned to the battleship OKLAHOMA for a year, again flying floatplanes. He became the senior aviator after two months. In April 1927, Spiv was assigned to the U.S.S. LANGLEY (CV-1), the Navy’s first aircraft carrier. After a year on the carrier, he became the commander officer for two years of a patrol squadron at the naval air station at Pearl Harbor (1928-1930). The squadron’s planes were long-range patrol seaplanes. A seaplane is a plane whose fuselage rests on the water, whereas a float plane sits above the water on “floats.” LEFT ABOVE: NHHC. During the 1930s, Spiv saw duty once again on a battleship as the senior aviator (U.S.S. CALIFORNIA, 1930-1933) and just over two years on aircraft carriers: U.S.S. LEXINGTON (CV-2), executive officer of a fighter squadron, 1935-1936); and USS YORKTOWN (CV-5), commanding officer of a fighter squadron, 1936-1938). He was also the commanding officer of a training plane squadron at the U.S. Naval Academy (19331935). My interest in Wake Island I have been fascinated with Wake Island since passing through there in 1959 and 1961 as an Air Force “brat.” In 1959, my father was assigned to Taiwan. To get there, we flew from Travis A.F.B., California, with layovers in Hawaii (then a territory), Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines (44 hours travel time). We flew on a military-chartered Boeing 377 Stratocruiser of Transocean Airlines (photo below). A retired military version of this plane (C-97G) is at the Don Q Inn in Dodgeville, Wisconsin. Tom Thomas, President of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall Transocean B-377 of Fame, helped fly the plane to Dodgeville in 1977. A retired refueling tanker version (KC-97G) is on display at Volk Field. Tom was a C-97 and KC-97 pilot in the Wisconsin Air National Guard. Wake Island Background. Wake Island is actually a small atoll made up of three islands: the main island of Wake Island, Wilkes Island, and Peale Island. The islands enclose a lagoon. Wake Island is 2,500 miles west of Hawaii and is on the other side of the International Dateline. It is where America’s day begins. For example, when it is one second past midnight on Monday morning on Wake Island, it is only one second past 7:00 a.m. on Sunday in Milwaukee. Juan Trippe, the founder of Pan American Airways, had the vision of a Pacific air route for his famous flying-boat Clippers. However, he needed a refueling stop between Midway Island and Guam. Researching nautical charts and ship logs at the New York Public Library, he “discovered” the uninhabited Wake Island. The first Clipper landed in the lagoon at Wake Island in 1935. Wake Island Defense. The Navy decided to beef up the defenses of several Pacific Islands, including Wake Island. It contracted with a consortium of contractors (“Contractors Pacific Naval Air Bases”) to construct facilities on the islands. The contractor for Wake Island was Morrison-Knudsen Company of RIGHT ABOVE: Public domain. 7 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

HISTORY HANGAR Boise, Idaho. The company’s first contingent arrived on January 8, 1941. Facilities would include two runways, a seaplane ramp, dredging of a larger channel between Wake and Wilkes, and facilities for submarines. Marines were also assigned to these islands, including Wake Island. A detachment of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion began to arrive on Wake Island in August 1941. The detachment was undermanned and not fully equipped. Unfortunately, the radar destined for Wake Island never left Hawaii. A Marine fighter aircraft squadron (VMF211) arrived on December 4, 1941 with its twelve F-4F-3 Wildcats. [As a lieutenant commander, Laurel Clark was the flight surgeon for this squadron in 1992-1994, Forward in Flight, Summer 2021. One of the photos in that article is one she took of Harrier jets over Wake Island—see page 9 of that issue.] Assignment to Wake Island. In mid-November 1941, Spiv had orders to command the naval air station on Johnston Island. On account of a “PRESENT EMERGENCY” [possibly a delay in another officer’s assignment], his orders were changed for “TEMPORARY DUTY AS THE OFFICER IN CHARGE OF ALL NAVAL ACTIVITIES ON WAKE ISLAND.” Further: “UPON COMPLETION THIS DUTY PROCEED CARRY OUT ORIGINAL ORDERS.” Spiv never made it to Johnston Island. Spiv arrived on Wake Island on November 28, 1941 as the commander of the naval air station which was still under construction. Under his command were Major James Devereux, commander of the Marine detachment (arrived October 14, 1941); Major Paul Putnam, commander of VMF-211 (arrived December 4, 1941); and all Navy personnel, including the engineer supervising the construction effort of Morrison-Knudsen (about 1,200 contractor personnel). Invasion and Surrender. Japanese bombers attacked Wake Island without warning on the same day as the Pearl Harbor attack. After two more days of bombing, a Japanese fleet attempted to invade the island. The Marines (shore batteries and airplanes) sank two ships and shot down several airplanes. The Japanese called off the invasion. However, the Japanese returned on December 23rd with a larger force that now included two aircraft carriers from the Pearl Harbor attack. The Japanese landed troops on both Wilkes Island and Wake Island. Despite fierce fighting, it was apparent that the defenders on Wake Island were overwhelmed. In light of these circumstances, Spiv surrendered the island to the Japanese (after first changing into his blue dress uniform). 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame For his actions, Spiv was awarded the Navy Cross, the second highest military decoration. Devereux and Putnam were also awarded the Navy Cross. Relief Task Force Called Back. Admiral Kimmel, commander of the United States Pacific Fleet, had ordered a task force (with the carrier SARATOGA) under Admiral Fletcher to reinforce Wake Island. Kimmel was relieved from command days later and replaced by Vice Admiral Pye. With delays to the task force, intelligence about possible Japanese carriers near Wake Island, and being informed that the Japanese had landed on the island, Pye ordered the task force back to Hawaii (then about 425 miles from the island). Upon receiving the order, Fletcher threw his hat down in disgust but nevertheless complied. Pye’s order has been the subject of much discussion by historians over time. Murders by the Japanese. After the surrender, the Japanese passenger ship, Nitta Maru, transported most of the personnel on the island to Japan. Conditions were terrible: overcrowding, lack of sanitary conditions, beatings, and men being poorly fed. After the 12-day trip to Japan and in retaliation, the Japanese beheaded five Americans, used their bodies for bayonet practice, and then threw them overboard. The Japanese kept a number of Morrison-Knudsen employees on the island to help with its fortifications. The United States bombed Wake Island in October 1943. The Japanese general, fearing an invasion, ordered the contractor employees (98 of them) to the beach where they were machine gunned to death. One person managed to escape, but was soon captured. He was brought to the general, who beheaded him. The general was later convicted of war crimes and hung on Guam in 1946. There were several Morrison-Knudsen employees from Wisconsin who were murdered: Frank and Melvin Migacz and Alvin Streblow. A number of employees had signed several sun helmets. The first helmet photo (next page at right) is a close-up of Streblow’s signature, and the second helmet photo (next page at right) has more signatures and a drawing of Wake Island. Not every captured employee was killed. Another Wisconsin employee of Morrison-Knudsen, William Harper, was more fortunate. Harper survived the war in a POW camp in Osaka, Japan. He passed away at the age of 92 in 2009. ABOVE LEFT: VMF-211 emblem (in public domain) ABOVE RIGHT: Spiv on Nitta Maru (photo courtesy of Greg Cunningham)

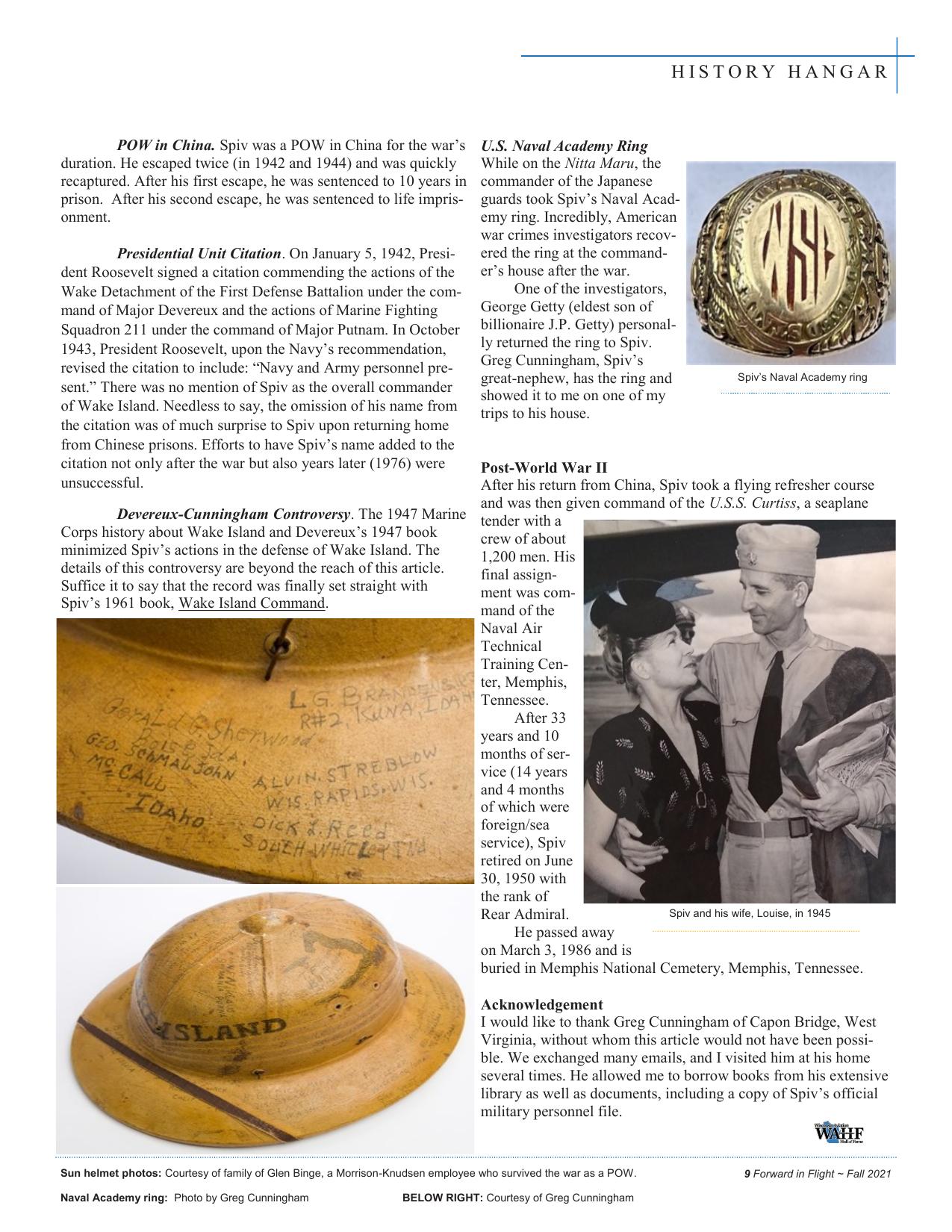

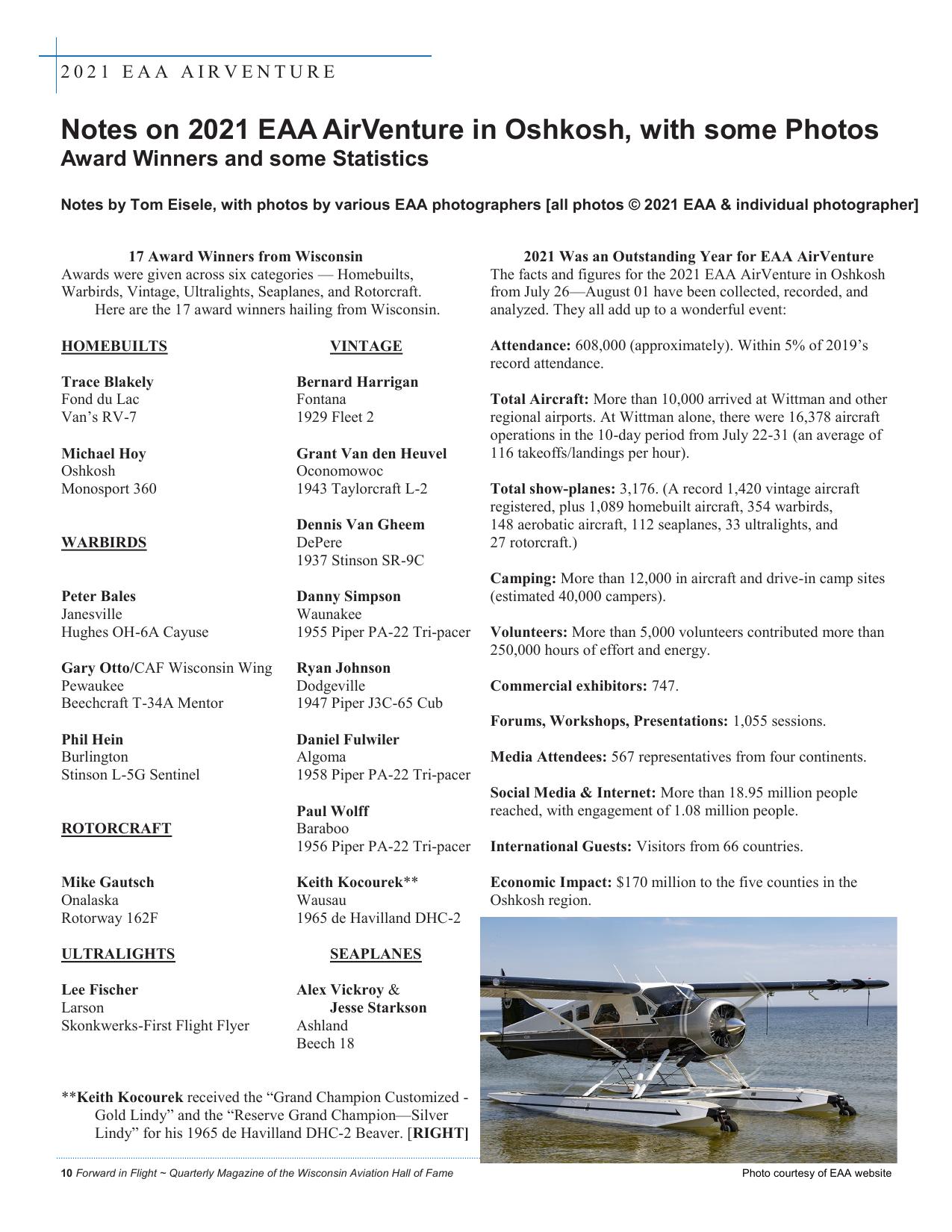

HISTORY HANGAR POW in China. Spiv was a POW in China for the war’s duration. He escaped twice (in 1942 and 1944) and was quickly recaptured. After his first escape, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. After his second escape, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. Presidential Unit Citation. On January 5, 1942, President Roosevelt signed a citation commending the actions of the Wake Detachment of the First Defense Battalion under the command of Major Devereux and the actions of Marine Fighting Squadron 211 under the command of Major Putnam. In October 1943, President Roosevelt, upon the Navy’s recommendation, revised the citation to include: “Navy and Army personnel present.” There was no mention of Spiv as the overall commander of Wake Island. Needless to say, the omission of his name from the citation was of much surprise to Spiv upon returning home from Chinese prisons. Efforts to have Spiv’s name added to the citation not only after the war but also years later (1976) were unsuccessful. U.S. Naval Academy Ring While on the Nitta Maru, the commander of the Japanese guards took Spiv’s Naval Academy ring. Incredibly, American war crimes investigators recovered the ring at the commander’s house after the war. One of the investigators, George Getty (eldest son of billionaire J.P. Getty) personally returned the ring to Spiv. Greg Cunningham, Spiv’s great-nephew, has the ring and showed it to me on one of my trips to his house. Spiv’s Naval Academy ring Post-World War II After his return from China, Spiv took a flying refresher course and was then given command of the U.S.S. Curtiss, a seaplane Devereux-Cunningham Controversy. The 1947 Marine tender with a Corps history about Wake Island and Devereux’s 1947 book crew of about minimized Spiv’s actions in the defense of Wake Island. The 1,200 men. His details of this controversy are beyond the reach of this article. final assignSuffice it to say that the record was finally set straight with ment was comSpiv’s 1961 book, Wake Island Command. mand of the Naval Air Technical Training Center, Memphis, Tennessee. After 33 years and 10 months of service (14 years and 4 months of which were foreign/sea service), Spiv retired on June 30, 1950 with the rank of Spiv and his wife, Louise, in 1945 Rear Admiral. He passed away on March 3, 1986 and is buried in Memphis National Cemetery, Memphis, Tennessee. Acknowledgement I would like to thank Greg Cunningham of Capon Bridge, West Virginia, without whom this article would not have been possible. We exchanged many emails, and I visited him at his home several times. He allowed me to borrow books from his extensive library as well as documents, including a copy of Spiv’s official military personnel file. Sun helmet photos: Courtesy of family of Glen Binge, a Morrison-Knudsen employee who survived the war as a POW. Naval Academy ring: Photo by Greg Cunningham BELOW RIGHT: Courtesy of Greg Cunningham 9 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

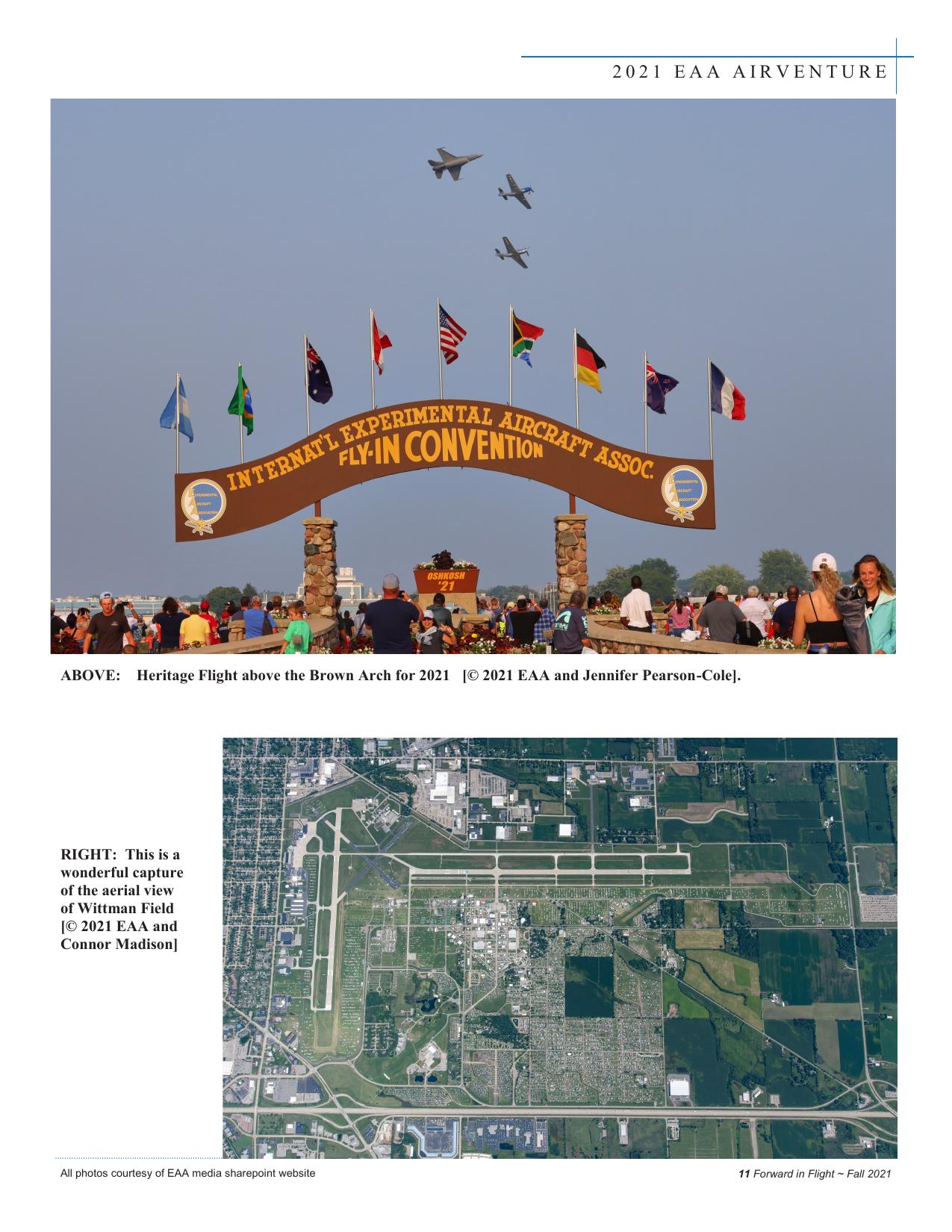

2021 EAA AIRVENTURE Notes on 2021 EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh, with some Photos Award Winners and some Statistics Notes by Tom Eisele, with photos by various EAA photographers [all photos © 2021 EAA & individual photographer] 17 Award Winners from Wisconsin Awards were given across six categories — Homebuilts, Warbirds, Vintage, Ultralights, Seaplanes, and Rotorcraft. Here are the 17 award winners hailing from Wisconsin. 2021 Was an Outstanding Year for EAA AirVenture The facts and figures for the 2021 EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh from July 26—August 01 have been collected, recorded, and analyzed. They all add up to a wonderful event: HOMEBUILTS VINTAGE Attendance: 608,000 (approximately). Within 5% of 2019’s record attendance. Trace Blakely Fond du Lac Van’s RV-7 Bernard Harrigan Fontana 1929 Fleet 2 Michael Hoy Oshkosh Monosport 360 Grant Van den Heuvel Oconomowoc 1943 Taylorcraft L-2 WARBIRDS Dennis Van Gheem DePere 1937 Stinson SR-9C Peter Bales Janesville Hughes OH-6A Cayuse Danny Simpson Waunakee 1955 Piper PA-22 Tri-pacer Gary Otto/CAF Wisconsin Wing Pewaukee Beechcraft T-34A Mentor Ryan Johnson Dodgeville 1947 Piper J3C-65 Cub Phil Hein Burlington Stinson L-5G Sentinel Daniel Fulwiler Algoma 1958 Piper PA-22 Tri-pacer ROTORCRAFT Paul Wolff Baraboo 1956 Piper PA-22 Tri-pacer Total Aircraft: More than 10,000 arrived at Wittman and other regional airports. At Wittman alone, there were 16,378 aircraft operations in the 10-day period from July 22-31 (an average of 116 takeoffs/landings per hour). Total show-planes: 3,176. (A record 1,420 vintage aircraft registered, plus 1,089 homebuilt aircraft, 354 warbirds, 148 aerobatic aircraft, 112 seaplanes, 33 ultralights, and 27 rotorcraft.) Camping: More than 12,000 in aircraft and drive-in camp sites (estimated 40,000 campers). Volunteers: More than 5,000 volunteers contributed more than 250,000 hours of effort and energy. Commercial exhibitors: 747. Forums, Workshops, Presentations: 1,055 sessions. Mike Gautsch Onalaska Rotorway 162F Keith Kocourek** Wausau 1965 de Havilland DHC-2 ULTRALIGHTS SEAPLANES Lee Fischer Larson Skonkwerks-First Flight Flyer Media Attendees: 567 representatives from four continents. Social Media & Internet: More than 18.95 million people reached, with engagement of 1.08 million people. International Guests: Visitors from 66 countries. Economic Impact: $170 million to the five counties in the Oshkosh region. Alex Vickroy & Jesse Starkson Ashland Beech 18 **Keith Kocourek received the “Grand Champion Customized Gold Lindy” and the “Reserve Grand Champion—Silver Lindy” for his 1965 de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver. [RIGHT] 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Photo courtesy of EAA website

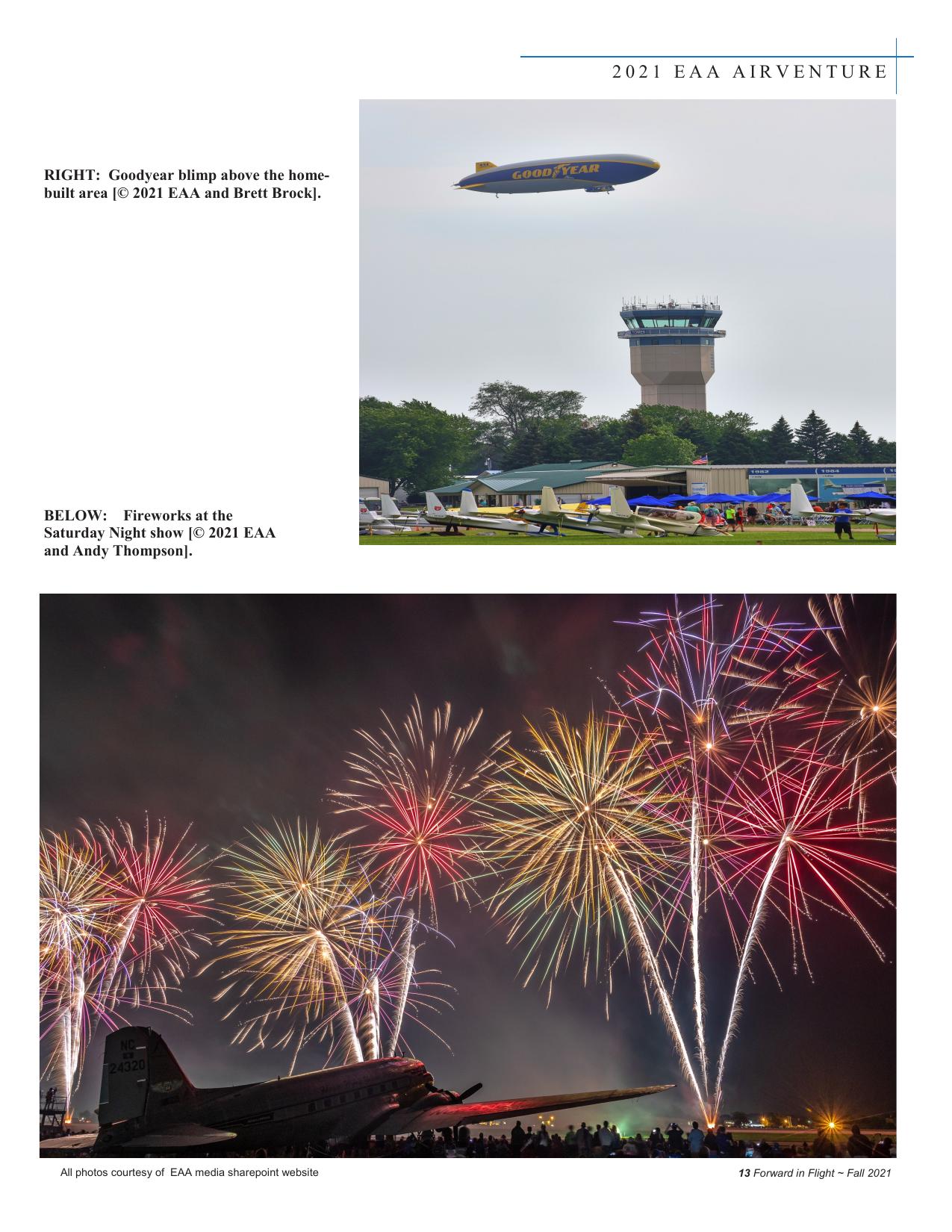

2021 EAA AIRVENTURE ABOVE: Heritage Flight above the Brown Arch for 2021 [© 2021 EAA and Jennifer Pearson-Cole]. RIGHT: This is a wonderful capture of the aerial view of Wittman Field [© 2021 EAA and Connor Madison] All photos courtesy of EAA media sharepoint website 11 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

2021 EAA AIRVENTURE ABOVE: A tight formation of the AeroShell Team at night in North American T-6’s [© 2021 EAA and Camden Thrasher]. LEFT: Tuskegee Airman Charles McGee at the commemorative event to mark the end of World War II [© 2021 EAA and Emil Vagjrt]. RIGHT: P-51 “Crazy Horse” [© 2021 EAA and Emil Vagjrt]. 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All photos courtesy of EAA media sharepoint website

2021 EAA AIRVENTURE RIGHT: Goodyear blimp above the homebuilt area [© 2021 EAA and Brett Brock]. BELOW: Fireworks at the Saturday Night show [© 2021 EAA and Andy Thompson]. All photos courtesy of EAA media sharepoint website 13 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

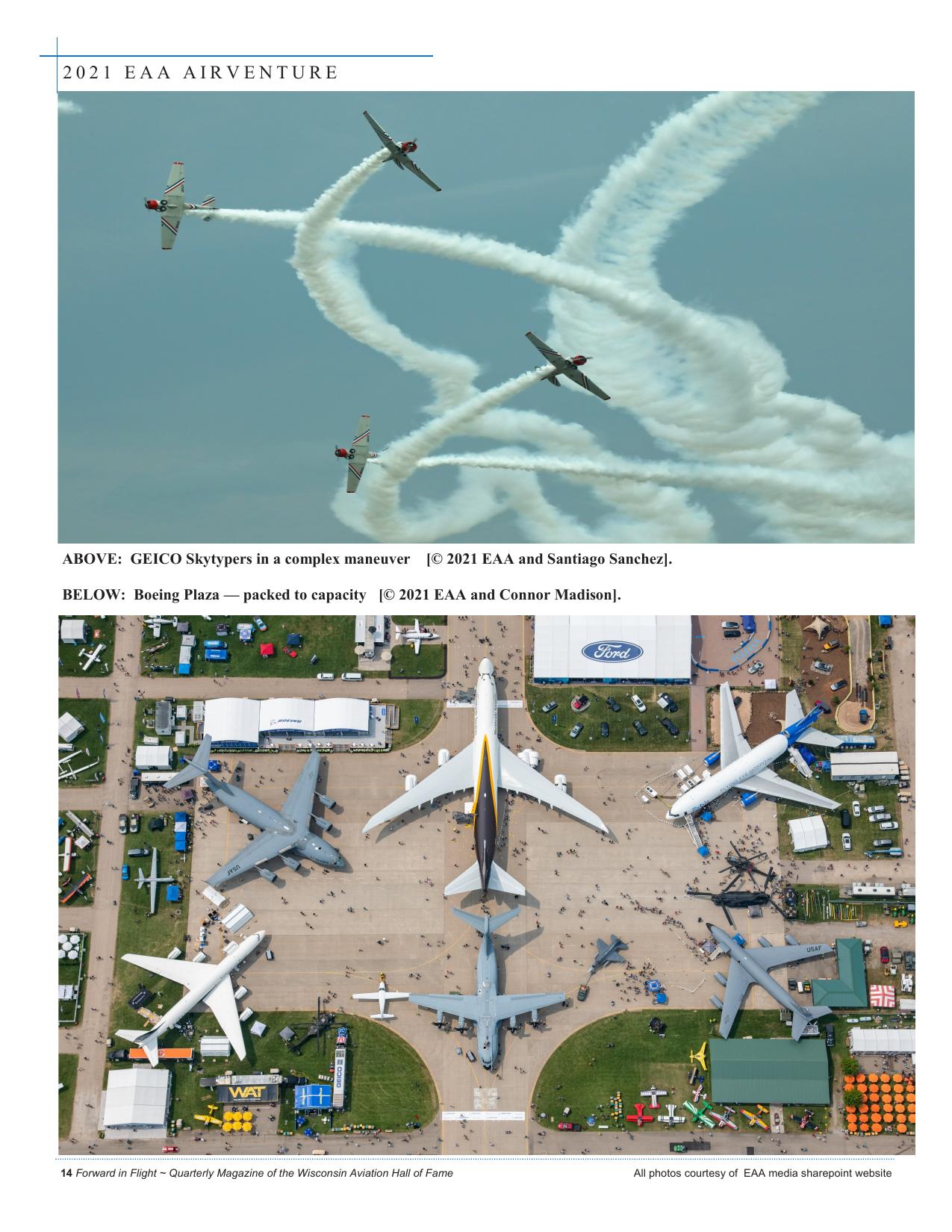

2021 EAA AIRVENTURE ABOVE: GEICO Skytypers in a complex maneuver [© 2021 EAA and Santiago Sanchez]. BELOW: Boeing Plaza — packed to capacity [© 2021 EAA and Connor Madison]. 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All photos courtesy of EAA media sharepoint website

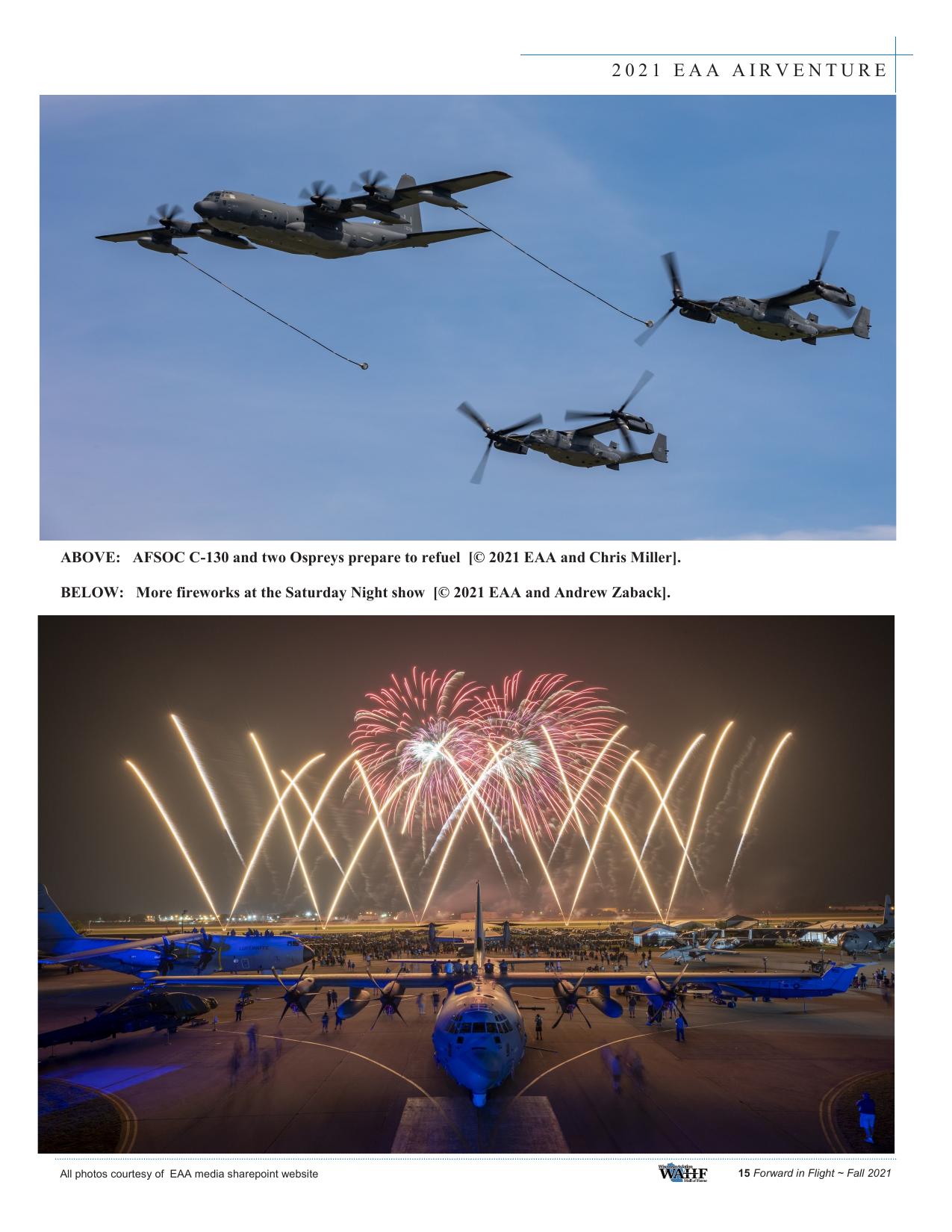

2021 EAA AIRVENTURE ABOVE: AFSOC C-130 and two Ospreys prepare to refuel [© 2021 EAA and Chris Miller]. BELOW: More fireworks at the Saturday Night show [© 2021 EAA and Andrew Zaback]. All photos courtesy of EAA media sharepoint website 15 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

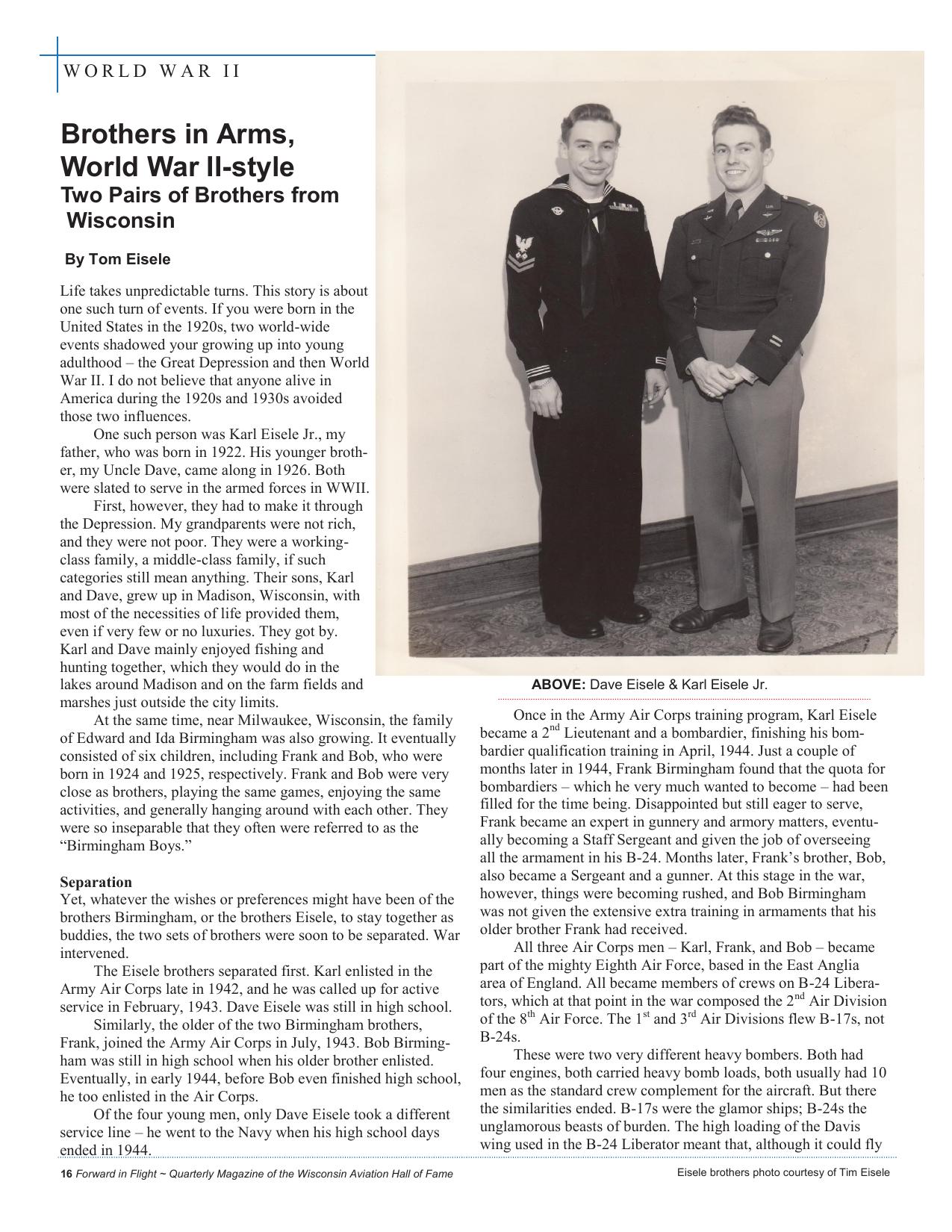

WORLD WAR II Brothers in Arms, World War II-style Two Pairs of Brothers from Wisconsin By Tom Eisele Life takes unpredictable turns. This story is about one such turn of events. If you were born in the United States in the 1920s, two world-wide events shadowed your growing up into young adulthood – the Great Depression and then World War II. I do not believe that anyone alive in America during the 1920s and 1930s avoided those two influences. One such person was Karl Eisele Jr., my father, who was born in 1922. His younger brother, my Uncle Dave, came along in 1926. Both were slated to serve in the armed forces in WWII. First, however, they had to make it through the Depression. My grandparents were not rich, and they were not poor. They were a workingclass family, a middle-class family, if such categories still mean anything. Their sons, Karl and Dave, grew up in Madison, Wisconsin, with most of the necessities of life provided them, even if very few or no luxuries. They got by. Karl and Dave mainly enjoyed fishing and hunting together, which they would do in the lakes around Madison and on the farm fields and marshes just outside the city limits. At the same time, near Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the family of Edward and Ida Birmingham was also growing. It eventually consisted of six children, including Frank and Bob, who were born in 1924 and 1925, respectively. Frank and Bob were very close as brothers, playing the same games, enjoying the same activities, and generally hanging around with each other. They were so inseparable that they often were referred to as the “Birmingham Boys.” Separation Yet, whatever the wishes or preferences might have been of the brothers Birmingham, or the brothers Eisele, to stay together as buddies, the two sets of brothers were soon to be separated. War intervened. The Eisele brothers separated first. Karl enlisted in the Army Air Corps late in 1942, and he was called up for active service in February, 1943. Dave Eisele was still in high school. Similarly, the older of the two Birmingham brothers, Frank, joined the Army Air Corps in July, 1943. Bob Birmingham was still in high school when his older brother enlisted. Eventually, in early 1944, before Bob even finished high school, he too enlisted in the Air Corps. Of the four young men, only Dave Eisele took a different service line – he went to the Navy when his high school days ended in 1944. 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ABOVE: Dave Eisele & Karl Eisele Jr. Once in the Army Air Corps training program, Karl Eisele became a 2nd Lieutenant and a bombardier, finishing his bombardier qualification training in April, 1944. Just a couple of months later in 1944, Frank Birmingham found that the quota for bombardiers – which he very much wanted to become – had been filled for the time being. Disappointed but still eager to serve, Frank became an expert in gunnery and armory matters, eventually becoming a Staff Sergeant and given the job of overseeing all the armament in his B-24. Months later, Frank’s brother, Bob, also became a Sergeant and a gunner. At this stage in the war, however, things were becoming rushed, and Bob Birmingham was not given the extensive extra training in armaments that his older brother Frank had received. All three Air Corps men – Karl, Frank, and Bob – became part of the mighty Eighth Air Force, based in the East Anglia area of England. All became members of crews on B-24 Liberators, which at that point in the war composed the 2 nd Air Division of the 8th Air Force. The 1st and 3rd Air Divisions flew B-17s, not B-24s. These were two very different heavy bombers. Both had four engines, both carried heavy bomb loads, both usually had 10 men as the standard crew complement for the aircraft. But there the similarities ended. B-17s were the glamor ships; B-24s the unglamorous beasts of burden. The high loading of the Davis wing used in the B-24 Liberator meant that, although it could fly Eisele brothers photo courtesy of Tim Eisele

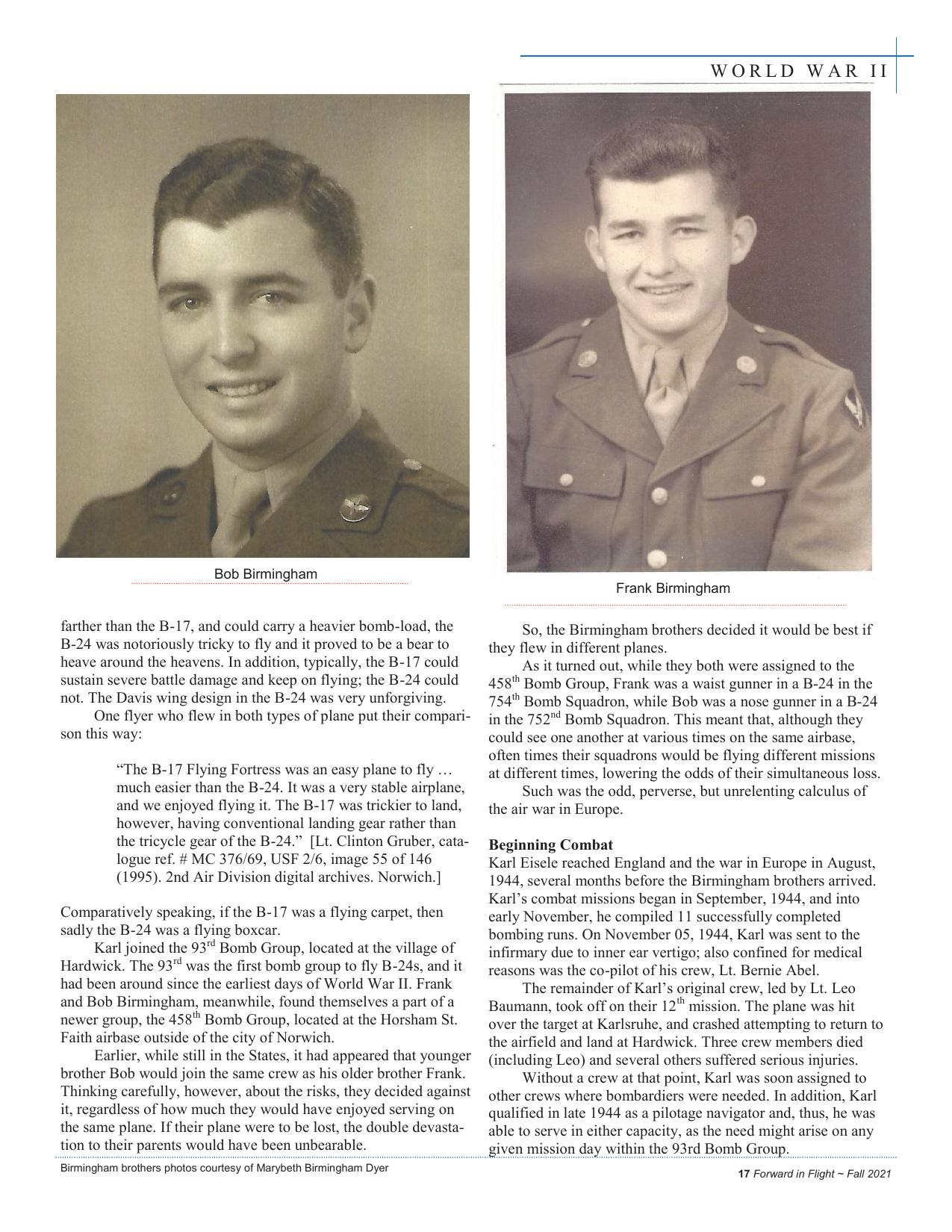

WORLD WAR II Bob Birmingham farther than the B-17, and could carry a heavier bomb-load, the B-24 was notoriously tricky to fly and it proved to be a bear to heave around the heavens. In addition, typically, the B-17 could sustain severe battle damage and keep on flying; the B-24 could not. The Davis wing design in the B-24 was very unforgiving. One flyer who flew in both types of plane put their comparison this way: “The B-17 Flying Fortress was an easy plane to fly … much easier than the B-24. It was a very stable airplane, and we enjoyed flying it. The B-17 was trickier to land, however, having conventional landing gear rather than the tricycle gear of the B-24.” [Lt. Clinton Gruber, catalogue ref. # MC 376/69, USF 2/6, image 55 of 146 (1995). 2nd Air Division digital archives. Norwich.] Comparatively speaking, if the B-17 was a flying carpet, then sadly the B-24 was a flying boxcar. Karl joined the 93rd Bomb Group, located at the village of Hardwick. The 93rd was the first bomb group to fly B-24s, and it had been around since the earliest days of World War II. Frank and Bob Birmingham, meanwhile, found themselves a part of a newer group, the 458th Bomb Group, located at the Horsham St. Faith airbase outside of the city of Norwich. Earlier, while still in the States, it had appeared that younger brother Bob would join the same crew as his older brother Frank. Thinking carefully, however, about the risks, they decided against it, regardless of how much they would have enjoyed serving on the same plane. If their plane were to be lost, the double devastation to their parents would have been unbearable. Birmingham brothers photos courtesy of Marybeth Birmingham Dyer Frank Birmingham So, the Birmingham brothers decided it would be best if they flew in different planes. As it turned out, while they both were assigned to the 458th Bomb Group, Frank was a waist gunner in a B-24 in the 754th Bomb Squadron, while Bob was a nose gunner in a B-24 in the 752nd Bomb Squadron. This meant that, although they could see one another at various times on the same airbase, often times their squadrons would be flying different missions at different times, lowering the odds of their simultaneous loss. Such was the odd, perverse, but unrelenting calculus of the air war in Europe. Beginning Combat Karl Eisele reached England and the war in Europe in August, 1944, several months before the Birmingham brothers arrived. Karl’s combat missions began in September, 1944, and into early November, he compiled 11 successfully completed bombing runs. On November 05, 1944, Karl was sent to the infirmary due to inner ear vertigo; also confined for medical reasons was the co-pilot of his crew, Lt. Bernie Abel. The remainder of Karl’s original crew, led by Lt. Leo Baumann, took off on their 12th mission. The plane was hit over the target at Karlsruhe, and crashed attempting to return to the airfield and land at Hardwick. Three crew members died (including Leo) and several others suffered serious injuries. Without a crew at that point, Karl was soon assigned to other crews where bombardiers were needed. In addition, Karl qualified in late 1944 as a pilotage navigator and, thus, he was able to serve in either capacity, as the need might arise on any given mission day within the 93rd Bomb Group. 17 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

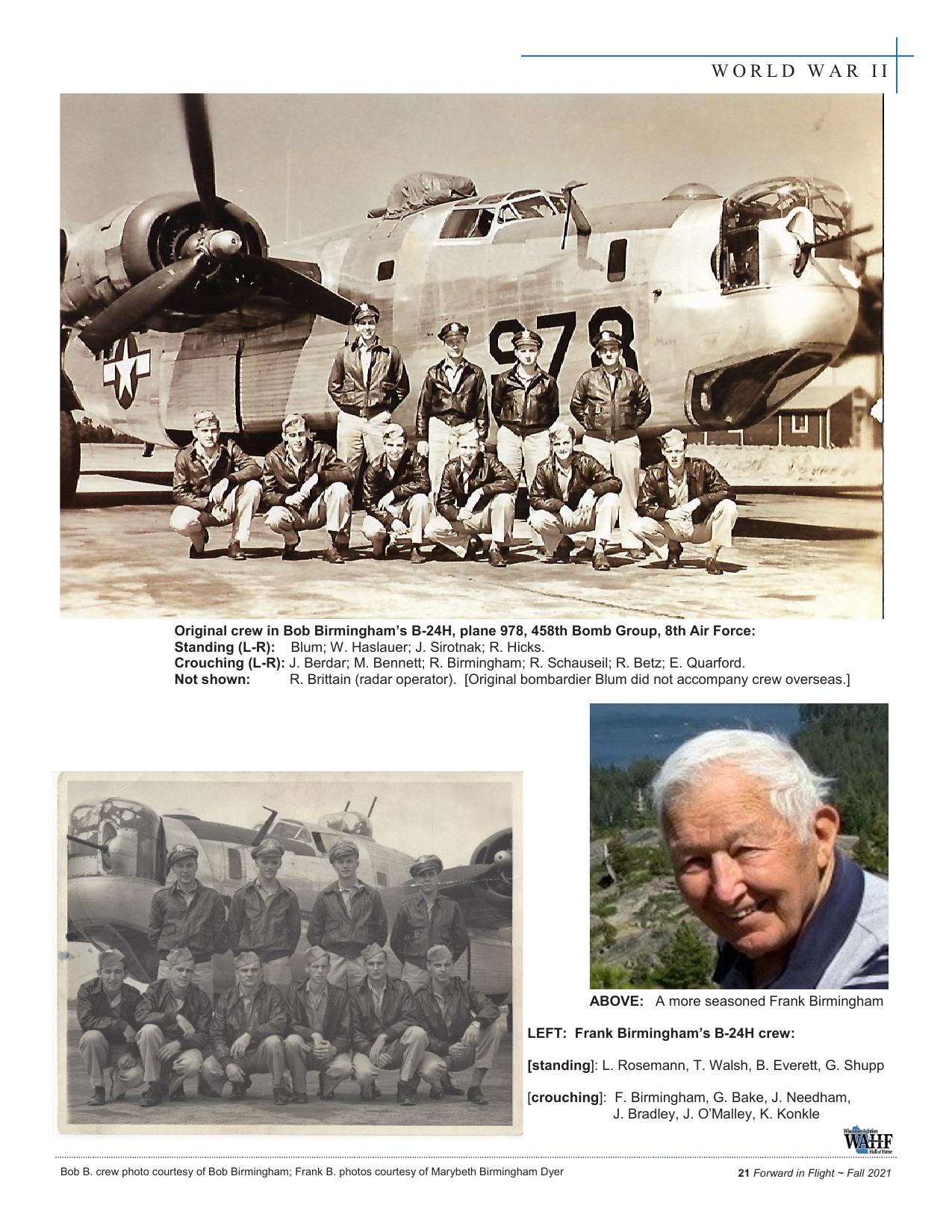

WORLD WAR II Meanwhile, the Birmingham brothers had arrived in England in late 1944. After much practice and training, they flew their first actual combat missions in December of that year. By mid-January, 1945, Frank Birmingham had 7 missions under his belt, Bob had 4 missions to his credit, and Karl Eisele had flown 19 missions. They all had become experienced veterans of the air war. Mission 798 January 17, 1945 saw the 798th mission to be flown by the 8th Air Force. It was a dual effort, with 450 heavy bombers TOP: H. Gruener, R. White, T. Steph, C. Cline, K. Eisele, J. Floore heading to southern Germany and 225 heavy bombers heading BOTTOM: W. Tipton, P. Golden, A. Chipman, H. Busse, C. Trone to northern Germany. Frank Birmingham didn’t fly that mission, since he had just bomb drop could be reached, “Full House” was hit with a close flak burst near the right wing. The shrapnel from the blast puncflown the day before, on January 16th. But Karl Eisele flew on tured the right-side of the pilot’s cabin and struck co-pilot HarMission 798, as did Bob Birmingham. Both of them were flying rington in the head, fatally wounding him. The plane’s “Mickey” in the northern stream of bombers, heading toward oil refineries operator, Lt. Charles Kline, was also injured, albeit less seriousand U-Boat pens in the vicinity of Hamburg. No experienced flyer in the 8th Air Force wanted to face the ly. The flak burst also totally disabled engine #4 and partially disabled engine #3, leaving the B-24J hobbled. guns around Hamburg. It was a pit – second only, perhaps, to The ship slowly slid out of formation. Berlin – a veritable cauldron of anti-aircraft fire. At this stage in The “Full House” was too badly damaged to face the return the war, there were more than 440 anti-aircraft guns in installahead winds coming from England. Yet the plane was not totally tions surrounding Hamburg. Why so many guns? Because of incapacitated. It could coast on two engines, while it gradually what they protected. The German war machine ran on oil, and a suburb of Ham- lost power and lost altitude. Major Floore and Capt. Gruener decided it would be best, all things considered, to try to reach the burg (called Harburg) was still operating important oil refineries neutral country of Sweden, across the Baltic Sea. This required at the time. As well, German U-boats still were a threat to shipdodging German flak, and possibly German fighters, as the crew ping in the North Atlantic, and this meant that the submarine and their plane slowly made their way north toward Denmark, pens around Hamburg needed to be destroyed, or at least supand then northeast toward Sweden. The two navigators – Capt. pressed. White and Lt. Eisele – gave the pilots the course. Despite the need, however, no Allied flyer wanted to run Happily, they made it. The “Full House” was seen leaving that anti-aircraft gauntlet. Consider, for example, what another the formation on its bomb run over Hamburg at 12:09 pm. Later, flyer on this same Mission 798 said about his feelings of appreat 1:45 pm, the injured B-24J safely set down near Malmo, hension: Sweden, escorted in to the Swedish airfield by Swedish fighters. Along their route, they had jettisoned much heavy equipment, “The next mission came on Jan 17. The briefing officer rolled up the screen, the red line went to HAMBURG! I dodged flak, and even took evasive action to avoid fire from a nearly fell through my seat, we were going straight over German ship on the Baltic. Still, they made it to Sweden. Sadly, although Lt. Harrington was rushed to a hospital, he the city, apparently because there was a wind blowing died from his wounds days later. Lt. Kline recovered fully from and that was the fastest way through the flak area. I sweated all the way to the target. Our group was quite a his wounds, however, and the crew – eleven men in all – served ways back in the bomber stream so I saw the first group out the remainder of the European war interned in Sweden. disappear behind the flak cloud.” [Lt. Walter F. Hughes, Bob’s story catalogue reference # MC 371/112, USF 2/6, image 61 of 115 (1990). 2ndAD digital archives. Norwich (UK).] What of Bob Birmingham, who also flew on this Mission 798? Bob’s B-24H in the 458th Bomb Group was farther back in the bomber stream stretching between England and Germany. PiKarl’s story loted by Lt. Roger Hicks and co-pilot J. M. Sirotnak, they steadiOn January 17th, for Mission 798, Karl Eisele was the pilotage navigator in the B-24J (called “Full House”), which was the dep- ly made their way toward the target, and their ship, unlike the “Full House,” made it to the “bombs away” point. But no farther. uty lead plane for the 93rd Bomb Group. Capt. Harry H. Gruener Immediately after Bob Birmingham toggled his bomb was the pilot at the controls and Lt. John Harrington was the copilot. As deputy lead for the group, their plane carried the deputy switch (as nose gunner, he was bombing on cue from the lead plane, watching when the lead bombardier dropped his bombs), command pilot, Major John W. Floore. their plane took a series of flak hits – in rapid succession, there At some point near Hamburg, the lead plane for the 93rd were explosions in the bomb bay area, at the waist, and in the BG had to abort (cause unknown). As deputy, Capt. Gruener tail. The flak shrapnel severed some of their gas lines and hyeased “Full House” into the lead, and at the Initial Point he took draulic lines. Almost immediately thereafter, Lt. Hicks had to the group into the bomb run. Suddenly, however, before the 18 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame “Full House” crew photo in 1945 from the collection of Karl Eisele Jr.

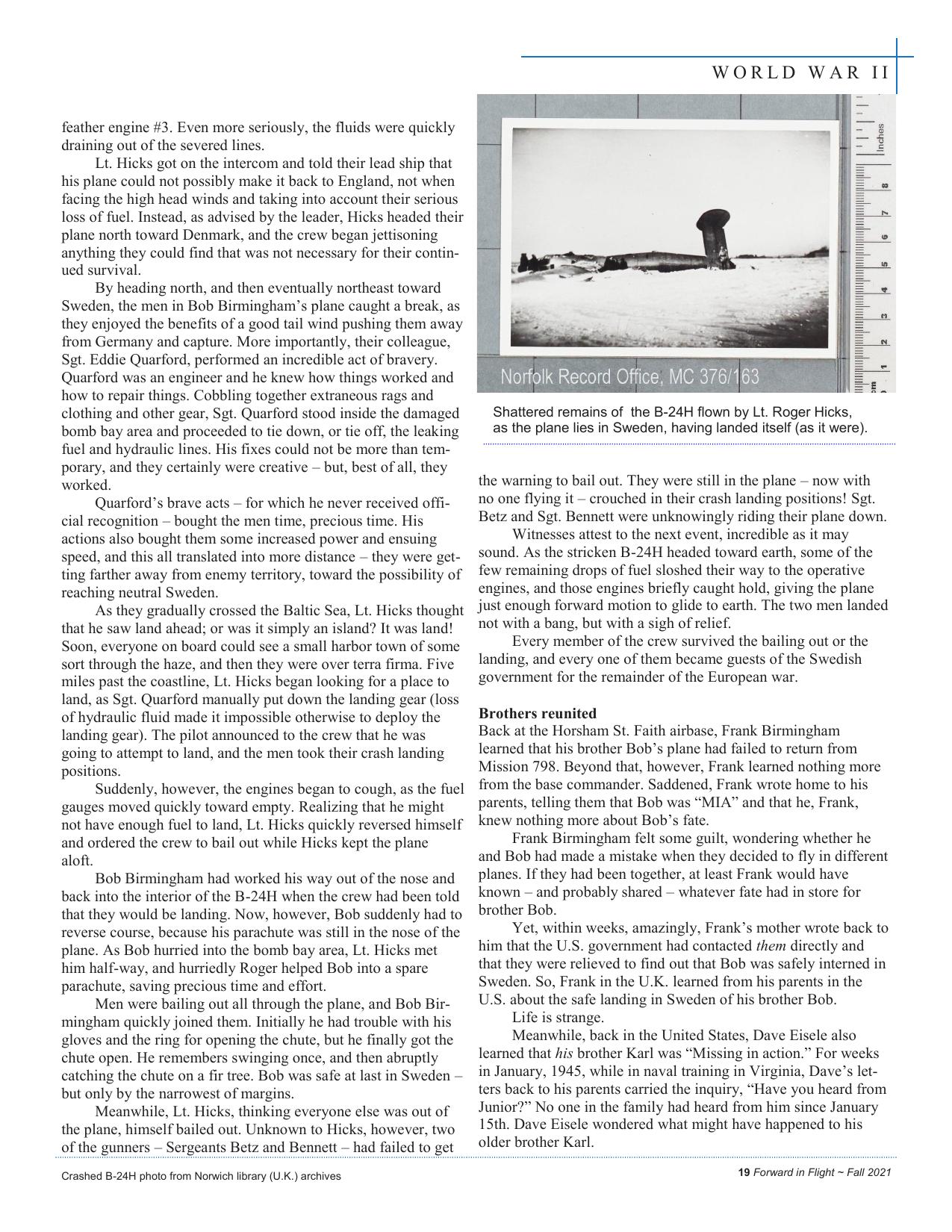

WORLD WAR II feather engine #3. Even more seriously, the fluids were quickly draining out of the severed lines. Lt. Hicks got on the intercom and told their lead ship that his plane could not possibly make it back to England, not when facing the high head winds and taking into account their serious loss of fuel. Instead, as advised by the leader, Hicks headed their plane north toward Denmark, and the crew began jettisoning anything they could find that was not necessary for their continued survival. By heading north, and then eventually northeast toward Sweden, the men in Bob Birmingham’s plane caught a break, as they enjoyed the benefits of a good tail wind pushing them away from Germany and capture. More importantly, their colleague, Sgt. Eddie Quarford, performed an incredible act of bravery. Quarford was an engineer and he knew how things worked and how to repair things. Cobbling together extraneous rags and clothing and other gear, Sgt. Quarford stood inside the damaged bomb bay area and proceeded to tie down, or tie off, the leaking fuel and hydraulic lines. His fixes could not be more than temporary, and they certainly were creative – but, best of all, they worked. Quarford’s brave acts – for which he never received official recognition – bought the men time, precious time. His actions also bought them some increased power and ensuing speed, and this all translated into more distance – they were getting farther away from enemy territory, toward the possibility of reaching neutral Sweden. As they gradually crossed the Baltic Sea, Lt. Hicks thought that he saw land ahead; or was it simply an island? It was land! Soon, everyone on board could see a small harbor town of some sort through the haze, and then they were over terra firma. Five miles past the coastline, Lt. Hicks began looking for a place to land, as Sgt. Quarford manually put down the landing gear (loss of hydraulic fluid made it impossible otherwise to deploy the landing gear). The pilot announced to the crew that he was going to attempt to land, and the men took their crash landing positions. Suddenly, however, the engines began to cough, as the fuel gauges moved quickly toward empty. Realizing that he might not have enough fuel to land, Lt. Hicks quickly reversed himself and ordered the crew to bail out while Hicks kept the plane aloft. Bob Birmingham had worked his way out of the nose and back into the interior of the B-24H when the crew had been told that they would be landing. Now, however, Bob suddenly had to reverse course, because his parachute was still in the nose of the plane. As Bob hurried into the bomb bay area, Lt. Hicks met him half-way, and hurriedly Roger helped Bob into a spare parachute, saving precious time and effort. Men were bailing out all through the plane, and Bob Birmingham quickly joined them. Initially he had trouble with his gloves and the ring for opening the chute, but he finally got the chute open. He remembers swinging once, and then abruptly catching the chute on a fir tree. Bob was safe at last in Sweden – but only by the narrowest of margins. Meanwhile, Lt. Hicks, thinking everyone else was out of the plane, himself bailed out. Unknown to Hicks, however, two of the gunners – Sergeants Betz and Bennett – had failed to get Crashed B-24H photo from Norwich library (U.K.) archives Shattered remains of the B-24H flown by Lt. Roger Hicks, as the plane lies in Sweden, having landed itself (as it were). the warning to bail out. They were still in the plane – now with no one flying it – crouched in their crash landing positions! Sgt. Betz and Sgt. Bennett were unknowingly riding their plane down. Witnesses attest to the next event, incredible as it may sound. As the stricken B-24H headed toward earth, some of the few remaining drops of fuel sloshed their way to the operative engines, and those engines briefly caught hold, giving the plane just enough forward motion to glide to earth. The two men landed not with a bang, but with a sigh of relief. Every member of the crew survived the bailing out or the landing, and every one of them became guests of the Swedish government for the remainder of the European war. Brothers reunited Back at the Horsham St. Faith airbase, Frank Birmingham learned that his brother Bob’s plane had failed to return from Mission 798. Beyond that, however, Frank learned nothing more from the base commander. Saddened, Frank wrote home to his parents, telling them that Bob was “MIA” and that he, Frank, knew nothing more about Bob’s fate. Frank Birmingham felt some guilt, wondering whether he and Bob had made a mistake when they decided to fly in different planes. If they had been together, at least Frank would have known – and probably shared – whatever fate had in store for brother Bob. Yet, within weeks, amazingly, Frank’s mother wrote back to him that the U.S. government had contacted them directly and that they were relieved to find out that Bob was safely interned in Sweden. So, Frank in the U.K. learned from his parents in the U.S. about the safe landing in Sweden of his brother Bob. Life is strange. Meanwhile, back in the United States, Dave Eisele also learned that his brother Karl was “Missing in action.” For weeks in January, 1945, while in naval training in Virginia, Dave’s letters back to his parents carried the inquiry, “Have you heard from Junior?” No one in the family had heard from him since January 15th. Dave Eisele wondered what might have happened to his older brother Karl. 19 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

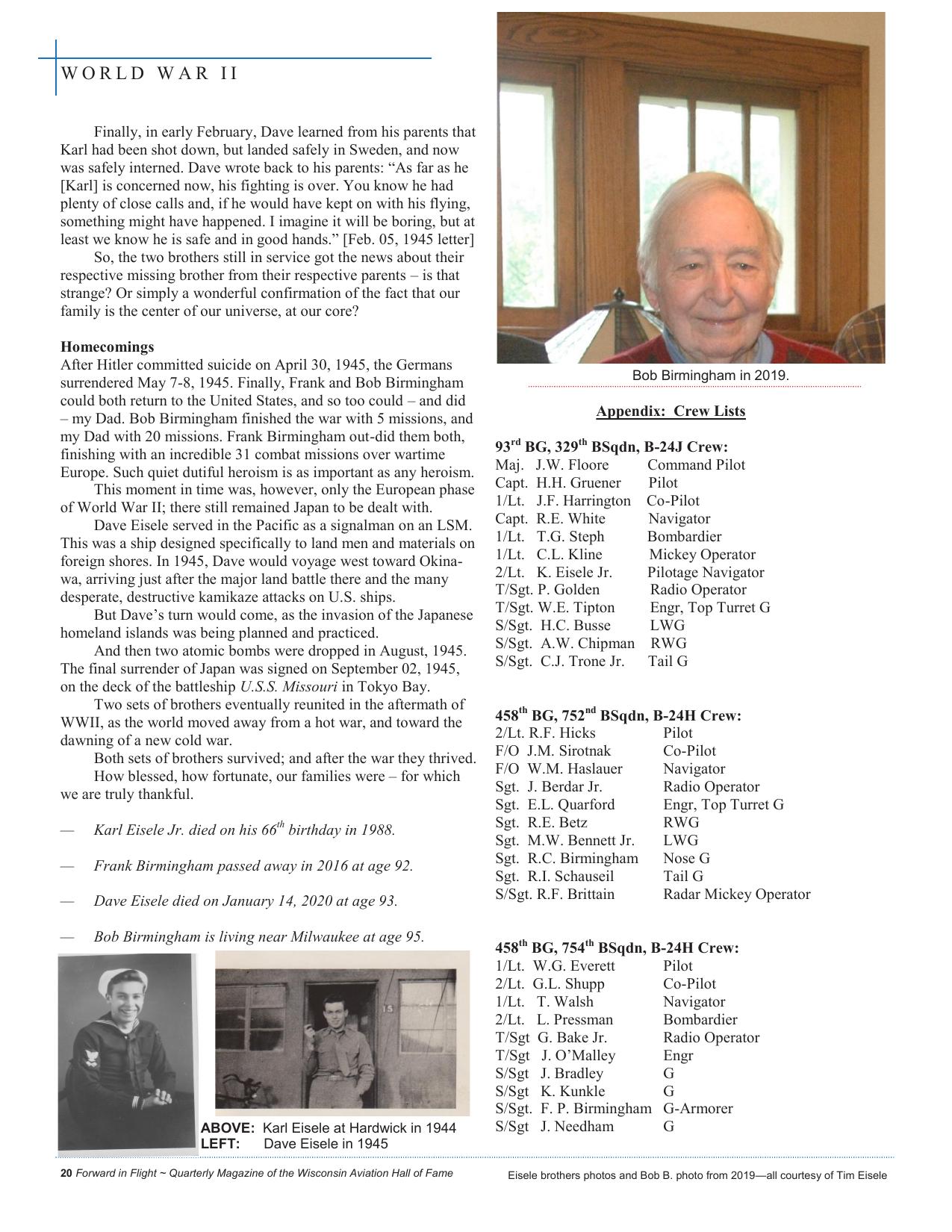

WORLD WAR II Finally, in early February, Dave learned from his parents that Karl had been shot down, but landed safely in Sweden, and now was safely interned. Dave wrote back to his parents: “As far as he [Karl] is concerned now, his fighting is over. You know he had plenty of close calls and, if he would have kept on with his flying, something might have happened. I imagine it will be boring, but at least we know he is safe and in good hands.” [Feb. 05, 1945 letter] So, the two brothers still in service got the news about their respective missing brother from their respective parents – is that strange? Or simply a wonderful confirmation of the fact that our family is the center of our universe, at our core? Homecomings After Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945, the Germans surrendered May 7-8, 1945. Finally, Frank and Bob Birmingham could both return to the United States, and so too could – and did – my Dad. Bob Birmingham finished the war with 5 missions, and my Dad with 20 missions. Frank Birmingham out-did them both, finishing with an incredible 31 combat missions over wartime Europe. Such quiet dutiful heroism is as important as any heroism. This moment in time was, however, only the European phase of World War II; there still remained Japan to be dealt with. Dave Eisele served in the Pacific as a signalman on an LSM. This was a ship designed specifically to land men and materials on foreign shores. In 1945, Dave would voyage west toward Okinawa, arriving just after the major land battle there and the many desperate, destructive kamikaze attacks on U.S. ships. But Dave’s turn would come, as the invasion of the Japanese homeland islands was being planned and practiced. And then two atomic bombs were dropped in August, 1945. The final surrender of Japan was signed on September 02, 1945, on the deck of the battleship U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Two sets of brothers eventually reunited in the aftermath of WWII, as the world moved away from a hot war, and toward the dawning of a new cold war. Both sets of brothers survived; and after the war they thrived. How blessed, how fortunate, our families were – for which we are truly thankful. — Karl Eisele Jr. died on his 66th birthday in 1988. — Frank Birmingham passed away in 2016 at age 92. — Dave Eisele died on January 14, 2020 at age 93. — Bob Birmingham is living near Milwaukee at age 95. ABOVE: Karl Eisele at Hardwick in 1944 LEFT: Dave Eisele in 1945 20 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Bob Birmingham in 2019. Appendix: Crew Lists 93rd BG, 329th BSqdn, B-24J Crew: Maj. J.W. Floore Command Pilot Capt. H.H. Gruener Pilot 1/Lt. J.F. Harrington Co-Pilot Capt. R.E. White Navigator 1/Lt. T.G. Steph Bombardier 1/Lt. C.L. Kline Mickey Operator 2/Lt. K. Eisele Jr. Pilotage Navigator T/Sgt. P. Golden Radio Operator T/Sgt. W.E. Tipton Engr, Top Turret G S/Sgt. H.C. Busse LWG S/Sgt. A.W. Chipman RWG S/Sgt. C.J. Trone Jr. Tail G 458th BG, 752nd BSqdn, B-24H Crew: 2/Lt. R.F. Hicks Pilot F/O J.M. Sirotnak Co-Pilot F/O W.M. Haslauer Navigator Sgt. J. Berdar Jr. Radio Operator Sgt. E.L. Quarford Engr, Top Turret G Sgt. R.E. Betz RWG Sgt. M.W. Bennett Jr. LWG Sgt. R.C. Birmingham Nose G Sgt. R.I. Schauseil Tail G S/Sgt. R.F. Brittain Radar Mickey Operator 458th BG, 754th BSqdn, B-24H Crew: 1/Lt. W.G. Everett Pilot 2/Lt. G.L. Shupp Co-Pilot 1/Lt. T. Walsh Navigator 2/Lt. L. Pressman Bombardier T/Sgt G. Bake Jr. Radio Operator T/Sgt J. O’Malley Engr S/Sgt J. Bradley G S/Sgt K. Kunkle G S/Sgt. F. P. Birmingham G-Armorer S/Sgt J. Needham G Eisele brothers photos and Bob B. photo from 2019—all courtesy of Tim Eisele

WORLD WAR II Original crew in Bob Birmingham’s B-24H, plane 978, 458th Bomb Group, 8th Air Force: Standing (L-R): Blum; W. Haslauer; J. Sirotnak; R. Hicks. Crouching (L-R): J. Berdar; M. Bennett; R. Birmingham; R. Schauseil; R. Betz; E. Quarford. Not shown: R. Brittain (radar operator). [Original bombardier Blum did not accompany crew overseas.] ABOVE: A more seasoned Frank Birmingham LEFT: Frank Birmingham’s B-24H crew: [standing]: L. Rosemann, T. Walsh, B. Everett, G. Shupp [crouching]: F. Birmingham, G. Bake, J. Needham, J. Bradley, J. O’Malley, K. Konkle Bob B. crew photo courtesy of Bob Birmingham; Frank B. photos courtesy of Marybeth Birmingham Dyer 21 Forward in Flight ~ Fall 2021

SHORT STORY Threading the Needle For Steve, who loves to fly By Dean Zakos I loved being in the air. I was 26 years old, tall and gangly, in 1972. I was the newbie First Officer sitting in the right seat of a Grumman Gulfstream G159. The aircraft was owned by a large consumer products company. Our day started early at our home base, Milwaukee’s Mitchell Field. Nine of our fourteen seats were filled on this flight. Businessmen using the corporate airplane. We climbed out at about 1,900 feet per minute into scattered fair weather cumulus and took in the expanse of a blue-green Lake Michigan as we turned on course to the south. The destination was Jackson, Mississippi (KJAN), where we would overnight. Then, on to El Paso, Texas (KELP). At the end of day two, back to Jackson, overnighting again. Returning to KMKE the following morning. It was summertime. The 24 and 36 hour prog charts showed a low pressure system developing in the southwestern United States. The leg from El Paso back to Jackson looked like it may be a challenge, with several lines of showers and thunderstorms, some severe, forecast to move across west, central, and east Texas along our line of flight. I wanted to look sharp for the captain on this trip. I had flown with him a few times before. Occasionally, as the First Officer; more frequently, as the “relief” pilot to spell the captain or the FO on longer trip segments. On flights when I flew as the relief pilot, the captain would often refer to me as “ballast.” I had about 30 hours in the G159. I had a lot to learn. I knew it – and the captain knew it. The captain’s name was O’Brien. Everyone called him “Obie.” He was a hard drinking, hard talking Irishman, with a penchant for fifths of Jameson, foul-smelling cigars, and randy limericks, of which he seemed to have a never-ending supply. “There once was a man from Boston, Mass, whose balls were made of brass. In stormy weather, when they clicked together, lightning would shoot out of his a--.” You get the idea. Regardless of his taste in jokes, I held him in high regard. Obie soloed in civilian life in the late 1930s and was well positioned for a flying slot in the Army Air Corps at the start of World War II. He flew B-25 Mitchells for the Fifth Air Force in the Southwest Pacific. I am told he became adept at low level strafing of Japanese shipping and dropping parafrag bombs on jungle airfields. He earned a DFC and several Air Medals. If asked, he would say he was only doing his job – the same as everyone else. I was not so sure. Was just any pilot capable of leading and flying missions, often in rotten weather, and at mast height or treetop level, all while getting shot at? Obie stayed with the flying game after the war, trying the airlines both in the United States and in South America. A few brief stints in Africa and the Middle East. He seemed to like to move around. His only constant companion was his old, wornleather liquor case, which he made sure was carried on and off each flight. That was one of my primary responsibilities as FO. 22 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Obie had seen a great deal of the world out of a cockpit window, and all the weather the world could throw at him. My logbook and career were a little thin at this point. I had some interest in airplanes growing up, but no passion. I did well in my high school classes; played some sports; chased some girls. In college, I studied electrical engineering, but excelled mostly at shooting pool, drinking beer, and staying out late. My grades suffered. I questioned my commitment. I heard about a ground school being offered for thirty dollars. Curious, I signed up, attended the classes, and passed the written test. There was a small airport close by – one paved runway and one turf runway. I soloed at age 20 in a Piper J3 Cub in 1966 on Mother’s Day. Five dollars (wet) per hour for the airplane rental and five dollars per hour for the instructor. From the moment of that solo, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. I next travelled to California to attend a flying school to pick up my commercial and instrument ratings. With 250 – 300 hours, the small commuter airlines would start to look at me. The flying business then is like now - there is an ebb and flow to it, and timing is everything. My timing was lousy, and I missed out on the airline jobs out there. Instead, I found a job instructing in the Chicago area. While building time, I picked up my multi-engine rating in a Piper Apache. I remember clearly how little airspace there was to worry about at the time. No Chicago Class Bravo. No TFRs. The airspace restrictions we see today sort of creeped up on us over time. I am not complaining about the present system, but looking back, there was a freedom to take off and go that simply does not exist today. In late 1968, I thought I was on the way to my airline career. I had an interview scheduled with Air Wisconsin in Appleton. Unfortunately, Uncle Sam had other plans for me. I enjoyed a deferment from the draft until my classification was changed to 1A that November. A letter inviting me to join the US Army (well, actually, insisting) quickly followed. I trained as a mechanic on AH-1G Cobra attack helicopters. I received orders in August 1969 to report to the Bien Hoa airbase in South Vietnam, with refueling stops in Alaska and Japan on the way over. I had a window seat on the arriving flight, and I still remember my disbelief, while looking down as we crossed the Vietnamese coastline, how a country with such beautiful blue ocean water, white sand beaches, and lush tropical greenery, could be in the midst of a real shooting war. The other first impression in-country was sticking my head out of the transport on landing and feeling like I was stepping into an oven. The heat was oppressive. I got used to it. The guys that had been there awhile could always tell who was new. The experienced hands recognized which shells whistling constantly overhead were incoming or outgoing; I