Forward in Flight - Spring 2017

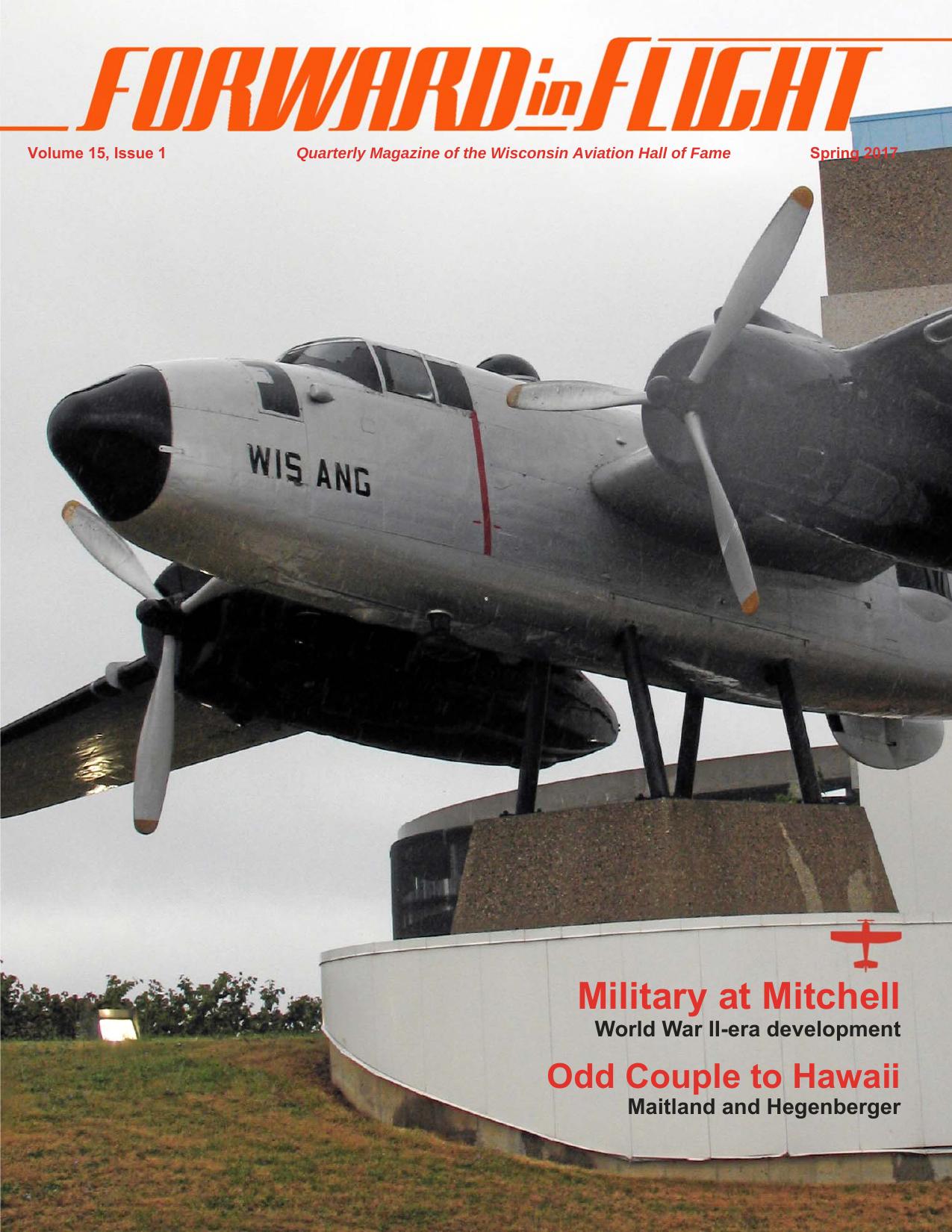

Volume 15, Issue 1 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Spring 2017 Military at Mitchell World War II-era development Odd Couple to Hawaii Maitland and Hegenberger

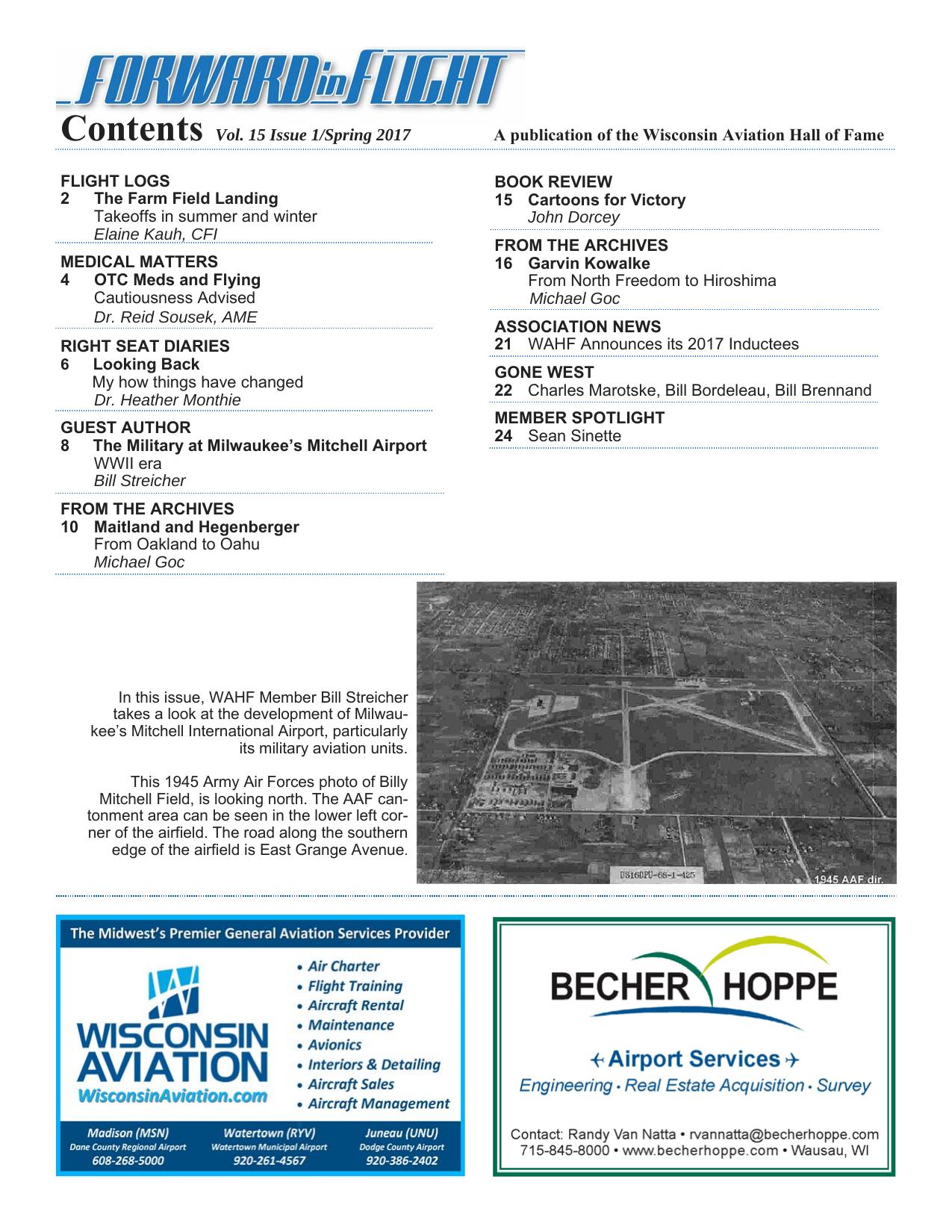

Contents Vol. 15 Issue 1/Spring 2017 A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame FLIGHT LOGS 2 The Farm Field Landing Takeoffs in summer and winter Elaine Kauh, CFI BOOK REVIEW 15 Cartoons for Victory John Dorcey MEDICAL MATTERS 4 OTC Meds and Flying Cautiousness Advised Dr. Reid Sousek, AME RIGHT SEAT DIARIES 6 Looking Back My how things have changed Dr. Heather Monthie GUEST AUTHOR 8 The Military at Milwaukee’s Mitchell Airport WWII era Bill Streicher FROM THE ARCHIVES 10 Maitland and Hegenberger From Oakland to Oahu Michael Goc In this issue, WAHF Member Bill Streicher takes a look at the development of Milwaukee’s Mitchell International Airport, particularly its military aviation units. This 1945 Army Air Forces photo of Billy Mitchell Field, is looking north. The AAF cantonment area can be seen in the lower left corner of the airfield. The road along the southern edge of the airfield is East Grange Avenue. FROM THE ARCHIVES 16 Garvin Kowalke From North Freedom to Hiroshima Michael Goc ASSOCIATION NEWS 21 WAHF Announces its 2017 Inductees GONE WEST 22 Charles Marotske, Bill Bordeleau, Bill Brennand MEMBER SPOTLIGHT 24 Sean Sinette

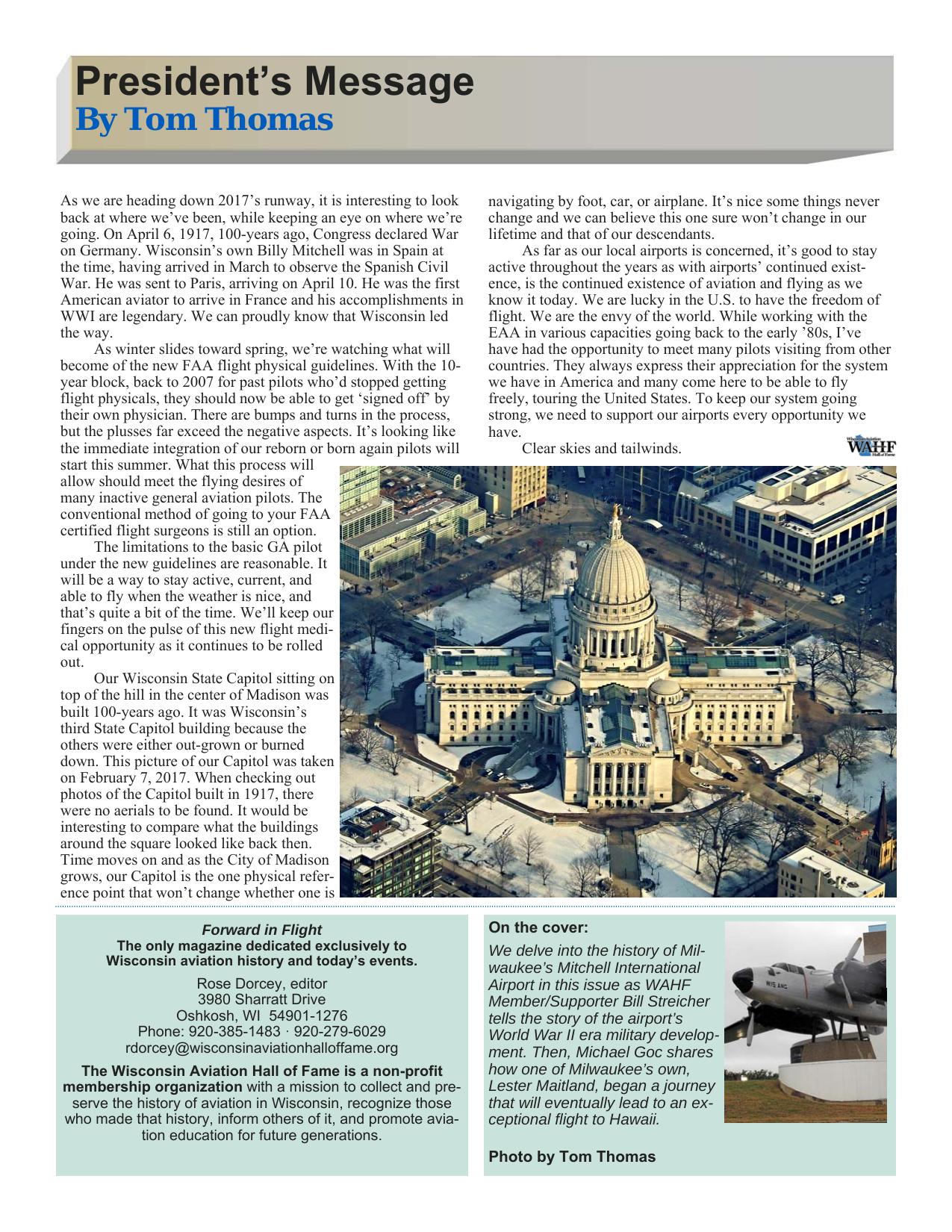

President’s Message By Tom Thomas As we are heading down 2017’s runway, it is interesting to look back at where we’ve been, while keeping an eye on where we’re going. On April 6, 1917, 100-years ago, Congress declared War on Germany. Wisconsin’s own Billy Mitchell was in Spain at the time, having arrived in March to observe the Spanish Civil War. He was sent to Paris, arriving on April 10. He was the first American aviator to arrive in France and his accomplishments in WWI are legendary. We can proudly know that Wisconsin led the way. As winter slides toward spring, we’re watching what will become of the new FAA flight physical guidelines. With the 10year block, back to 2007 for past pilots who’d stopped getting flight physicals, they should now be able to get ‘signed off’ by their own physician. There are bumps and turns in the process, but the plusses far exceed the negative aspects. It’s looking like the immediate integration of our reborn or born again pilots will start this summer. What this process will allow should meet the flying desires of many inactive general aviation pilots. The conventional method of going to your FAA certified flight surgeons is still an option. The limitations to the basic GA pilot under the new guidelines are reasonable. It will be a way to stay active, current, and able to fly when the weather is nice, and that’s quite a bit of the time. We’ll keep our fingers on the pulse of this new flight medical opportunity as it continues to be rolled out. Our Wisconsin State Capitol sitting on top of the hill in the center of Madison was built 100-years ago. It was Wisconsin’s third State Capitol building because the others were either out-grown or burned down. This picture of our Capitol was taken on February 7, 2017. When checking out photos of the Capitol built in 1917, there were no aerials to be found. It would be interesting to compare what the buildings around the square looked like back then. Time moves on and as the City of Madison grows, our Capitol is the one physical reference point that won’t change whether one is Forward in Flight The only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s events. Rose Dorcey, editor 3980 Sharratt Drive Oshkosh, WI 54901-1276 Phone: 920-385-1483 · 920-279-6029 rdorcey@wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. navigating by foot, car, or airplane. It’s nice some things never change and we can believe this one sure won’t change in our lifetime and that of our descendants. As far as our local airports is concerned, it’s good to stay active throughout the years as with airports’ continued existence, is the continued existence of aviation and flying as we know it today. We are lucky in the U.S. to have the freedom of flight. We are the envy of the world. While working with the EAA in various capacities going back to the early ’80s, I’ve have had the opportunity to meet many pilots visiting from other countries. They always express their appreciation for the system we have in America and many come here to be able to fly freely, touring the United States. To keep our system going strong, we need to support our airports every opportunity we have. Clear skies and tailwinds. On the cover: We delve into the history of Milwaukee’s Mitchell International Airport in this issue as WAHF Member/Supporter Bill Streicher tells the story of the airport’s World War II era military development. Then, Michael Goc shares how one of Milwaukee’s own, Lester Maitland, began a journey that will eventually lead to an exceptional flight to Hawaii. Photo by Tom Thomas

FLIGHT LOGS The Farm Field Landing Why it’s fun to practice—just in case By Elaine Kauh It might sound strange to hear a pilot say, “It’s fun to practice for emergency landings!” Dealing with a real engine failure in flight is not fun. But it can be enjoyable to help prepare pilots safely manage such scenarios—just in case. This training combines the fundamentals of flying with a twist. You’re in a glide, maneuvering toward the ground without power. I recently enjoyed watching an experienced pilot maneuver our Cessna 172 toward a large field as he demonstrated how he would handle an engine failure. I began this simulated emergency about 2,000 feet above the ground and helped watch for traffic and obstacles as the pilot pointed out his landing site just ahead. He then flew sturns with gentle banks to dissipate altitude, saving enough until he knew he’d clear the road and make it to the field with room to spare. Then he deployed flaps and put the plane into a slip to steepen his descent towards the field. With a few hundred feet to go, we ended the “emergency” and climbed back up to 1,000 feet to fly home. One of the topics I love talking about with pilots who learned to fly some decades ago is how they routinely practiced forced landings all the way down to the hayfield or pasture they chose. Today, it’s rare to touch down off-airport and take off again. Still, the educational value of practicing flight with little or no power can’t be overestimated. Pilots learn not only what to do in case of emergency, they’re gaining experience in controlling an airplane without engine thrust while judging winds, time, and distance along the ground as well as expanding their abilities to set up for landing in varying situations. And so, we rehearse periodically to keep those skills fresh--just in case. The forced landing and its related skills have been part of flying since its inception. But the real difference between offfield landing practice then and now lies in that last 500 feet above the fields. Decades ago, pilots-in-training could practice landing off-airport and depart again without worrying too much about causing a ruckus on the ground, in part because non -pilots were more accustomed to seeing small planes do it. The “precautionary landing” on a farmer’s field was also routinely accepted. What if your engine was still running, but it was getting weak and rough? What if the oil temperature was rising to the top limit, or the oil pressure was dropping? You’d simply find a suitable spot and land. Then you’d see if you could figure out the problem, and maybe fix it or at least make it safe enough to get home. If not, you’d come back later in the farmer’s truck with what you needed to make repairs. The precautionary landing also was a great tool for waiting out bad weather, rather than pressing on trying to get to the home airport (something that occurs far too often today). I’ve known pilots who have enjoyed landing on farm fields just to “drop in” on neighbors and say hello. But things change over time, and today a few factors keep us from continuing that last few hundred feet to land on open fields (or least those we haven’t been to before or haven’t received permission to land on.) We stick to the “500foot” regulation for rural areas, which state that aircraft must be flown at least 500 feet from people, buildings, vehicles, and such. In a large field with no one around and the nearest farm building a half-mile away, landing would be perfectly legal. But doing so would bring lots of attention to that pilot because everyone would assume it was an actual emergency, and many would not appreciate finding out that he was “just practicing.” And regardless of that pilot’s skill and good intentions, there is always a chance of damage or injury; thus, it’s not worth the risk. And so, to practice real landings during simulated emergencies, we use actual runways, whether they’re paved or turf. For everything up to that point, there is still great value during practice in surprising a pilot with a sudden pull of the throttle to create a simulated engine failure, then watching to see how well she carries out the proper procedures. About 500 feet from the field, we’ll execute a go-around and climb 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame (another valuable maneuver to practice). The most common memory list for power failures is simply A-B-C: Airspeed, Best Place to Land, Cross-Check. Fly the airplane and obtain best glide speed to help you stay aloft as long as possible. The “best place to land” can be a runway, taxiway, grassy field, or whatever is safest and most accessible, and into the wind as much as possible. Crosschecks have you quickly running through whatever you have time to do – checking fuel switches, the carburetor, and anything else you can troubleshoot while you circle ‘round your selected landing spot. And when you’re low enough (but not too low), you’ll set up for as normal a landing as possible. The only difference is you don’t have the opportunity to go around and try again, which is why it’s important to stay proficient at it. The B in A-B-C often sparks the most debate. If the engine fails and you’re forced to land on whatever happens to be nearby, how do you really know the best place? While there are some general guidelines to use, in the end it’s all up to the pilot’s judgment. Most training books urge pilots to find the most open, empty field possible, avoiding populated areas or areas with power lines to clear. Because they’re just about everywhere, farm fields are surely the best bet. But wait! What about in the fall, when tall, ripe, tough cornstalks, closely packed together, cover most of those fields? I’ve asked dozens of pilots of varying experience whether they’d be comfortable with a forced landing into a cornfield, and found that there isn’t much agreement. Some fear the corn would catch the wheels and flip the airplane over, while others say landing into the corn as slowly and normally as possible, treating the crops like trees, would be feasible in an emergency. I’ve heard the same reservations about soybean fields. Sure, those plants seem benign and close to the ground, but they’re also tough and can tangle up in the wheels, easily flipping you over just before touchdown. The books discuss landing on plowed fields, but this also

FLIGHT LOGS Forced landings often require pilots to find a suitable off-airport site. Fields are usually the first choice, but quickly choosing the best one takes practice. seems to be problematic. Even if you can land along the furrows and into the wind as recommended, those piles of soil lined up along dug-up trenches are far deeper and rougher than you’d think, and a hard landing or turnover seem just as likely. Wisconsin pilots know that in the remote woods in the northern half of the state, you’re likely to glide down into a forest canopy because there aren’t other options. But with some forethought and good skill in emergency approaches, it can be done. We must remember that wherever you need to land, people come first and the airplane comes last. Landing under control and at the minimum safe airspeed is the best way to protect the occupants, even if the aircraft is destroyed as it takes the brunt of a landing in an undesirable spot, such as trees or corn. Using roads for emergency landings, compared to trees or terrain, also makes for lively discussions. As with the cornfield debate, it’s divided between those who go by the standard training that recommends avoiding roads, and Photo by Elaine Kauh those who say they’d never hesitate going for a road if that was the “best place to land.” The books usually point out the dangers of going for a road – poles with invisible wires, vehicles and pedestrians in the way, and obstacles on both sides. Look down from 1,000 feet at the twolane county highways that crisscross Wisconsin. While they’re mostly running straight for at least a couple of miles, leaving more than enough room to glide in, they’re narrow – leaving little margin for error to land on the centerline, often with wingtips reaching past either side. Then again, there are times when roads will be considered by some who don’t want to take their chances in tall corn, woods, rough fields, or along steep hillsides. Wider, open country roads – and many are devoid of traffic for miles – can usually be inspected for obstacles, and do provide smooth surfaces for landing. Meanwhile, you’d be about as close to help as you can be compared to going for a remote field. If you’re flying over mountainous terrain, roads might be the only choices for forced landings. Forced landings often require pilots to find a suitable off-airport site. Fields are usually the first choice, but quickly choosing the best one takes practice. In the end, it’s still a judgment call. It’s well within a pilot’s authority to do what’s necessary to safely manage any emergency, whether it’s landing on a field or road. Every flight is different, which makes each one a lesson in itself. Therefore, I like to collect the opinions and experiences from as many pilots as I can and share their ideas. Some of the simplest differences, like 500 feet worth of air, might not have changed how we learn to fly, but it does change the flight experience. Fewer and fewer of us can say we had fun gliding down to the neighbor’s hayfield just to say hello. Elaine Kauh is a flight instructor and aviation writer who enjoys around Wisconsin and elsewhere. Email Elaine at: ekauh@wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org 3 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017

MEDICAL MATTERS OTC Meds and Flying Cautiousness advised Dr. Reid Sousek, AME We live in a world full of acronyms. On social media, we have LOL, SMH, IDK, and the crude but common, WTF. In aviation, we have acronyms such as VOR, SIGMET, AME, GUMP, and even WTF applied here as well. In the medical world, we are full of even more acronyms. GERD, HA, CP, SOB, DOE, CHF, LH, FOS (Gastroesophageal reflux disease, headache, chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, congestive heart failure, lightheaded, and the occasional: full-of-s%&t). This article will focus on a common medical acronym OTC (over-the-counter). These are not necessarily harmless or dangerous. They are real medications. We mustn’t take the approach that if you can get it without a prescription it is safe and without side-effects. Particularly in the flying world, we need to be cautious not only with the side effects of medications but also the longer-term complications of a medication and interactions with other medications. Additionally, should you really be flying if a new condition is severe enough to require meds? New prescription medications, even ones with well understood pharmacology (a blood pressure medication for example) require a minimum seven days to watch for stability. The same level of precaution should be considered with a new over-thecounter medication. Although most of these would not be over-the-counter if they were truly dangerous; in the aviation setting, we must be even more vigilant when considering potential side effects and medication interactions. Let’s start up top. What about headache meds? There are numerous options out there ranging from Aspirin to Naproxen to Ibuprofen to Tylenol to Excedrin. Aspirin is a common medication, often used more for its preventive purposes than other benefits. Most preventive recommendations are for a low dose such as 81mg or 325 mg. We treat pain with aspirin at doses 650- to 1000-mg four times a day. In that setting of preventive daily use, I would expect the patient is tolerating the medication well and aware of their typical adverse reaction profile, if any. These chronic conditions are going to be thoroughly evaluated prior to medical certification and will be known to be stable. The more concerning would be a pilot developing a significant headache requiring treatment. Would flying be recommended? In this case, the concern is not the medication side effects, but rather the condition itself. Ibuprofen and Naproxen are two common OTC NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) often used for multiple different conditions (pain, fever, inflammation). Ibuprofen may carry a brand name such as Advil or Motrin or may be labeled as a store brand. Naproxen may go by trade names such as Aleve or Anaprox. These medications are like Aspirin in that they themselves are not an issue (unless you have an allergy to one), but other ingredients in the pill might be. Is it a combination “cold and flu” medicine? Tylenol, or acetaminophen (paracetamol for our European friends), is another pain and fever medication. In general, Tylenol is well tolerated; however, you must be careful to monitor the dosing. It is generally recommended to stay below 4 grams (4000mg) per 24 hours. Excedrin is an example of a headache medication with multiple active ingredients: Excedrin contains three active ingredients acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine. A component of Excedrin that many are familiar with is caffeine. Caffeine is an active medication that we obviously find in many places beyond headache meds. We often fail to think of caffeine as a medication or drug. Extra strength Excedrin has 65mg of caffeine per tablet. So, with a typical 2-tab dose you are getting 130mg. Four-hundred milligrams is generally offered as a loose upper limit for daily caffeine consumption. Going above 400mg may lead to agitation and irritability (in severe cases irregular heart rhythm or seizures), especially if not accustomed to larger doses. When using OTC meds, it’s sometimes best to stay grounded rather than risk the side effects while in the air. 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame

MEDICAL MATTERS The amount of caffeine in coffee varies depending on brewing technique, but the general range is 100mg to 200mg. A cola may have 25-50mg of caffeine, while energy drinks may have 200mg or more. This is not to throw Coke and Pepsi under the bus; but, rather to show we must be aware of everything we consume when we fly. If you have your normal two cups of coffee and then add in a Red Bull or Excedrin, you may be well above the 400mg recommendation and experience adverse symptoms. Keeping track of doses of the components of combination medications is important. If you take two Excedrin tabs, 250mg each, and take two extra strength Tylenol (500mg each) you will have 1500mg of APAP (acetaminophen) on board. It would be easy to go over the 4000mg max if repeatedly dosing at this level AhChoo Allergies are another common affliction among both pilots and the general population. The common OTC medications that may be used for allergies include Benadryl (diphenhydramine), Allegra (fexofenadine), Claritin/Alavert (loratadine), and Chlortan (chlorpheniramine). Even though these all end in “-ine” there are drastic differences in side effect profiles. The main difference is whether they cross the blood-brain barrier. Fexofenadine and Loratadine do not cause sedation as they do not cross the blood-brain barrier. These would be the preferred choice in a pilot. Again, however, you don’t want to take a Claritin and find out on descent from the Flight Levels that you can’t clear your ears. Other options for treatment of nasal symptoms include nasal sprays. Over the past few years’ nasal steroids such as Flonase and Nasonex have become available without a prescription. These will not provide immediate relief of symptoms. Instead, these two work preventively and must be used regularly for close to a week before symptom improvement is noted. In general, nasal steroids are relatively safe with nose bleeds, headaches, and cough as main side effects. As with any medication, there are other random and rarer side effects, so testing your reaction to a new medication for a few weeks is good practice. There is quite a bit of overlap with the cold/cough/flu remedies and allergy treatments. Many cold and flu remedies will have an anti-histamine component, thus potentially sedating effects. Decongestants and mucolytics make up the other common ingredients of cold and flu meds. (With NyQuil type medications you may see up to 10% Ethanol, a no-no for a pilot.) Components of these combination cold and flu remedies may include dextromethorphan, guaifenesin, phenylephrine, or pseudoephedrine. Dextromethorphan is a frequent ingredient added to suppress a cough. Dextromethorphan is a common culprit causing agitation, irritability, and nervousness. The down side is the potential to interact with other medications. It may cause serotonin syndrome if taken with other medications that affect serotonin. Serotonin syndrome is a condition that can result in hallucinations, racing heart, muscle twitching/cramping, confusion, and other scary side effects. Another concerning feature of dextromethorphan is the high variability in metabolism. Genetic factors can play a role, in some individuals the half-life is 2-3 hours, in others it is 24 hours. Phenylephrine and pseudoephedrine are alpha-adrenergic Photo courtesy of Rose Dorcey and alpha-/beta- adrenergic agonists, respectively. They are commonly added to cold and flu medications to help with nasal congestion. The potential adverse reaction list reads like a career criminal’s rap sheet. Seizure, confusion, hallucination, ringing ears, double vision, dizziness, heart arrhythmia, urinary retention, and weakness are a few of the glaring potential reactions. Do these happen frequently? Not necessarily, but again you don’t want to discover any of these reactions during a flight. Additionally, adding a few cups of coffee or other caffeine sources may aggravate these reactions even further. Guaifenesin is a common component of cough/cold/flu medications to help thin the mucus/phlegm. Here again, dizziness and drowsiness are potential issues. Sleep Aids It is obvious that taking a sleep aid immediately prior to flight is a huge no-no for a pilot-in-command. But, what about the situation where you are struggling to fall asleep around midnight and pop a few Unisom to catch some sleep before a 6 a.m. wakeup call? Unisom, SleepTabs, Simply Sleep are a few common products seen in any pharmacy aisle. These use diphenhydramine or doxylamine as the active ingredient (many common sleep aides use anti-histamines as the active agents). As we discussed previously, some anti-histamines cross the blood-brain barrier…those that do will cause sedation. The Histamine H1 receptor promotes wakefulness…therefore an anti-histamine that blocks the effects of histamine will cause “anti-wakefulness.” Blocking the H1 receptors in the skin will help with itching or allergic responses. In the brain, it is time for the pillow. This may be beneficial as you lay in bed looking at the red numbers of the alarm clock… but not as you are trying to copy your clearance or are in cruise on autopilot. Diphenhydramine’s half-life ranges from 7 to 12 hours in adults and may be up to 9 to 18 hours in the elderly. The FAA’s general rule is waiting 4-5 half-lives for a medication. The maximum half-life is used in this calculation, so the FAA recommends 60 hours. A 2011 FAA report (Drug and Alcohol in Civil Aviation Accident Pilot Fatalities from 2004-2008) shows that diphenhydramine is the most common drug found in pilots who have died in aviation accidents. Another study I came across while looking for data for this article tested driving performance after taking fexofenadine (non -sedating antihistamine), diphenhydramine (sedating antihistamine), and Alcohol compared to placebo (Ann Intern Med. 2000 Mar 7;132(5):354-63). In a driving simulator, they scored ability to match speed of another vehicle, lane keeping, and ability to react to suddenly blocked lanes in 40 individuals after taking each of the above. Fexofenadine did not affect driving tasks any more than placebo. Diphenhydramine, however, resulted in worse driving performance than 0.1% BAC (blood alcohol content). Interestingly the decreased performance did not correlate to perceived drowsiness. Therefore, just because you don’t feel tired doesn’t mean you are not affected. This article alone may have been all you need to fall asleep. With this discussion of OTC meds, you may think, “WTF, is anything safe?” Yes, these meds are generally safe so long as you watch interactions with other medications you take and keep in mind potential side effects. Or, maybe an underlying illness means you just shouldn’t fly today. TTYL (talk to you later). 5 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES Looking Back My how things have changed By Dr. Heather Monthie This summer will be 20 years since I first started flying. It was 1997 and I was a 19-year-old girl who had dreamed of learning to fly ever since I took a field trip to the airport when I was in kindergarten. I turned 20 years old right after I took my first few lessons, so I soloed shortly after my 20th birthday. I guess I can officially say that I have been a pilot for 20 years, but I have been involved in aviation for closer to 30. I am a general aviation pilot, not a professional charter or airline pilot. There have been so many changes in general aviation in the past 20 years, it’s natural for me to reflect on some of them. Recreational Pilot vs Sport Pilot The sport pilot certificate didn’t exist 20 years ago. The only option for someone not really needing a private certificate was the recreational pilot certificate. Many of us thought that if a student were to complete the requirements to become a recreational pilot, we might as well go ahead and just complete the requirements to become a private pilot. The recreational pilot certificate requires fewer hours for completion, but has it limitations. A recreational pilot can only fly within 50 nautical miles of the airport, can only fly during the day, and only fly in airspace where two-way communications aren’t necessary. The private pilot certificate requires just a few hours more for completion, so the recreational certificate was not as popular. In 2004, the sport pilot certificate was introduced, which created a whole new industry within aviation. We saw companies created around the concept of the new light-sport aircraft (LSA). Existing aviation companies had to figure out how to break into this new market. The sport pilot certificate and lightsport aircraft helped lower the barrier to entry for many aviators and has been a significant change to aviation in the last 13 years. Airport Security is Stronger Shortly after I earned my private pilot certificate, I got a job working line service at the local fixed-based operator (FBO). I remember being able to walk in the front door, walk past the front desk, and right out the door leading to the ramp or the hangars. No questions asked. Even if you didn’t work at the airport, if you walked in looking like you knew where you were going, you had free reign of where you went. Aircraft renters and owners would just open the ramp gates on their own, drive their car out onto the ramp, and do what they needed to do. As long as you didn’t drive your car on a con6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame trolled surface such as a taxiway or runway, you were fine. One night, I was working a quiet, overnight shift. A woman jumped the fence at the airport “just to see what would happen.” I saw her do it and she started walking toward the ramp where all of the regional airlines kept their aircraft overnight. I ran up to her and asked her what she was doing and that was the response I received. Airport authorities were notified and the woman was given a warning. As you can imagine, if something like this happened now the consequences would be quite different. Long gone are the days where we have open access to the airport! Technology The first airplane I flew had a VOR/DME, an ILS, NDB, and a Mode-C transponder all used for navigation. Very few had a hand-held GPS that could be used as a supplement in the airplane since these weren’t certified yet. I learned how to navigate by using checkpoints, and using an E6B as my flight “computer”. So, I guess you could say that I am one of the old-school pilots who don’t need all this fancy technology to fly—which is ironic because technology is my day job! Technology also has allowed us to move from printed Airport Facility Directories to electronic chart supplements. So much of the information we need to fly is electronic now. The days of 50-pound flight bags are pretty much gone for most of us! Aviation apps on our phones are a great way to keep up to date on all sorts of things. Twenty years ago, a 19- or 20-year-old having a car phone was probably a little ridiculous. If anything, we had pagers! Now, it seems kids are getting younger and younger when they get their first cell phone. I use my cell phone to check weather the most. Twenty years ago, I had to call the airport ATIS line to hear the automated recording. There are so many aviation apps available for your cell phone now. It’s easy to see nowadays how quickly technology is changing and how much more affordable it has become. Information is always in your hands. Our data is better protected now too. My first private pilot certificate proudly displayed my social security number and there was no way around it. Things finally got to the point where you could opt out and request a new pilot certificate number but it took some time. I remember working at a grocery store as a cashier in the mid-90s and some people still had their SSN printed on their checks. I remember thinking that was un-

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES necessary, then I received my pilot certificate with it on there! I was very thankful once I could request a new certificate number! The airmen database is a little better now at securing our information. It’s not 100% yet but much better than it was twenty years ago. I remember being able to look up anyone I wanted and finding out exactly where someone lived. Now you can at least opt out and not have your address information shared. Six Per Cent When I first started considering what it was going to take for me to get my pilot certificate, I kept seeing a statistic that female pilots are roughly 6% of the overall pilot population. This statistic has been going around since I first heard it in the early 1990s. Here we are in the later part of the 2010s and this statistic is still widely used in discussion. According to Women of Aviation Worldwide, we really have not made any progress in this area since about 1980. There was a spike of women getting interested in aviation and starting to pursue flying lessons around 1980. That number has dipped slightly, then leveled-off since then. We really haven’t made any progress in this area in the last 20 years. I am glad to see there hasn’t been a huge decline but it is disheartening to see that there hasn’t been more growth. Women of Aviation Worldwide wrote a great article you can find at: https://www.womenofaviationweek.org/five-decades-of-women -pilots-in-the-united-states-how-did-we-do/ One thing we have seen more of are organizations that are dedicated to promoting and celebrating women in aviation, and not just pilots. These organizations are supporting women air traffic controllers, mechanics, avionics technicians, and more. Social media has also helped to create a stronger community for women in aviation. When I started flying in 1997, I knew one other female pilot. Now, you can get on any of the major social media platforms and find a group of supportive women who love aviation. Many more retailers are creating nice merchandise to cater to female aviators. The choices of women’s clothing, gifts, jewelry, and other products is gradually increasing. One thing I love about social media is connecting with other women who love aviation and are creating businesses geared toward women who love aviation. The past 20 years has seen some major changes in the aviation world, and others haven’t changed so much. These are just a few of the changes that have happened in the last 20 years. Some of you may have just found the aviation world and not realize how much has changed. Others have been around for a while and have seen way more changes than I have! I am curious to know some of the other changes that have affected you in your general aviation flying. Find me on Facebook at FB.com/AdventurousAviatrix or on Twitter @DrMonthie. 7 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017

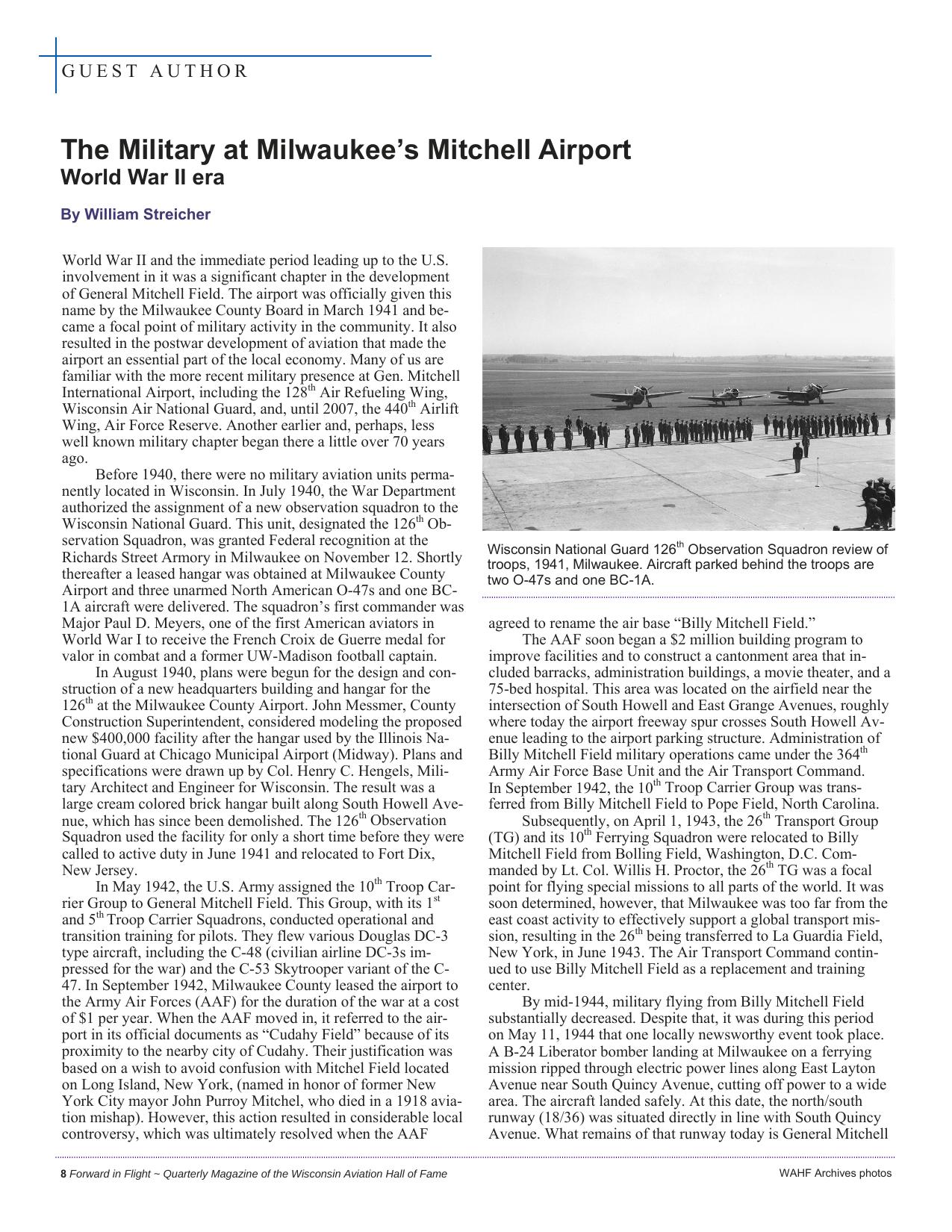

GUEST AUTHOR The Military at Milwaukee’s Mitchell Airport World War II era By William Streicher World War II and the immediate period leading up to the U.S. involvement in it was a significant chapter in the development of General Mitchell Field. The airport was officially given this name by the Milwaukee County Board in March 1941 and became a focal point of military activity in the community. It also resulted in the postwar development of aviation that made the airport an essential part of the local economy. Many of us are familiar with the more recent military presence at Gen. Mitchell International Airport, including the 128th Air Refueling Wing, Wisconsin Air National Guard, and, until 2007, the 440th Airlift Wing, Air Force Reserve. Another earlier and, perhaps, less well known military chapter began there a little over 70 years ago. Before 1940, there were no military aviation units permanently located in Wisconsin. In July 1940, the War Department authorized the assignment of a new observation squadron to the Wisconsin National Guard. This unit, designated the 126th Observation Squadron, was granted Federal recognition at the Richards Street Armory in Milwaukee on November 12. Shortly thereafter a leased hangar was obtained at Milwaukee County Airport and three unarmed North American O-47s and one BC1A aircraft were delivered. The squadron’s first commander was Major Paul D. Meyers, one of the first American aviators in World War I to receive the French Croix de Guerre medal for valor in combat and a former UW-Madison football captain. In August 1940, plans were begun for the design and construction of a new headquarters building and hangar for the 126th at the Milwaukee County Airport. John Messmer, County Construction Superintendent, considered modeling the proposed new $400,000 facility after the hangar used by the Illinois National Guard at Chicago Municipal Airport (Midway). Plans and specifications were drawn up by Col. Henry C. Hengels, Military Architect and Engineer for Wisconsin. The result was a large cream colored brick hangar built along South Howell Avenue, which has since been demolished. The 126th Observation Squadron used the facility for only a short time before they were called to active duty in June 1941 and relocated to Fort Dix, New Jersey. In May 1942, the U.S. Army assigned the 10th Troop Carrier Group to General Mitchell Field. This Group, with its 1st and 5th Troop Carrier Squadrons, conducted operational and transition training for pilots. They flew various Douglas DC-3 type aircraft, including the C-48 (civilian airline DC-3s impressed for the war) and the C-53 Skytrooper variant of the C47. In September 1942, Milwaukee County leased the airport to the Army Air Forces (AAF) for the duration of the war at a cost of $1 per year. When the AAF moved in, it referred to the airport in its official documents as “Cudahy Field” because of its proximity to the nearby city of Cudahy. Their justification was based on a wish to avoid confusion with Mitchel Field located on Long Island, New York, (named in honor of former New York City mayor John Purroy Mitchel, who died in a 1918 aviation mishap). However, this action resulted in considerable local controversy, which was ultimately resolved when the AAF 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Wisconsin National Guard 126th Observation Squadron review of troops, 1941, Milwaukee. Aircraft parked behind the troops are two O-47s and one BC-1A. agreed to rename the air base “Billy Mitchell Field.” The AAF soon began a $2 million building program to improve facilities and to construct a cantonment area that included barracks, administration buildings, a movie theater, and a 75-bed hospital. This area was located on the airfield near the intersection of South Howell and East Grange Avenues, roughly where today the airport freeway spur crosses South Howell Avenue leading to the airport parking structure. Administration of Billy Mitchell Field military operations came under the 364th Army Air Force Base Unit and the Air Transport Command. In September 1942, the 10th Troop Carrier Group was transferred from Billy Mitchell Field to Pope Field, North Carolina. Subsequently, on April 1, 1943, the 26th Transport Group (TG) and its 10th Ferrying Squadron were relocated to Billy Mitchell Field from Bolling Field, Washington, D.C. Commanded by Lt. Col. Willis H. Proctor, the 26th TG was a focal point for flying special missions to all parts of the world. It was soon determined, however, that Milwaukee was too far from the east coast activity to effectively support a global transport mission, resulting in the 26th being transferred to La Guardia Field, New York, in June 1943. The Air Transport Command continued to use Billy Mitchell Field as a replacement and training center. By mid-1944, military flying from Billy Mitchell Field substantially decreased. Despite that, it was during this period on May 11, 1944 that one locally newsworthy event took place. A B-24 Liberator bomber landing at Milwaukee on a ferrying mission ripped through electric power lines along East Layton Avenue near South Quincy Avenue, cutting off power to a wide area. The aircraft landed safely. At this date, the north/south runway (18/36) was situated directly in line with South Quincy Avenue. What remains of that runway today is General Mitchell WAHF Archives photos

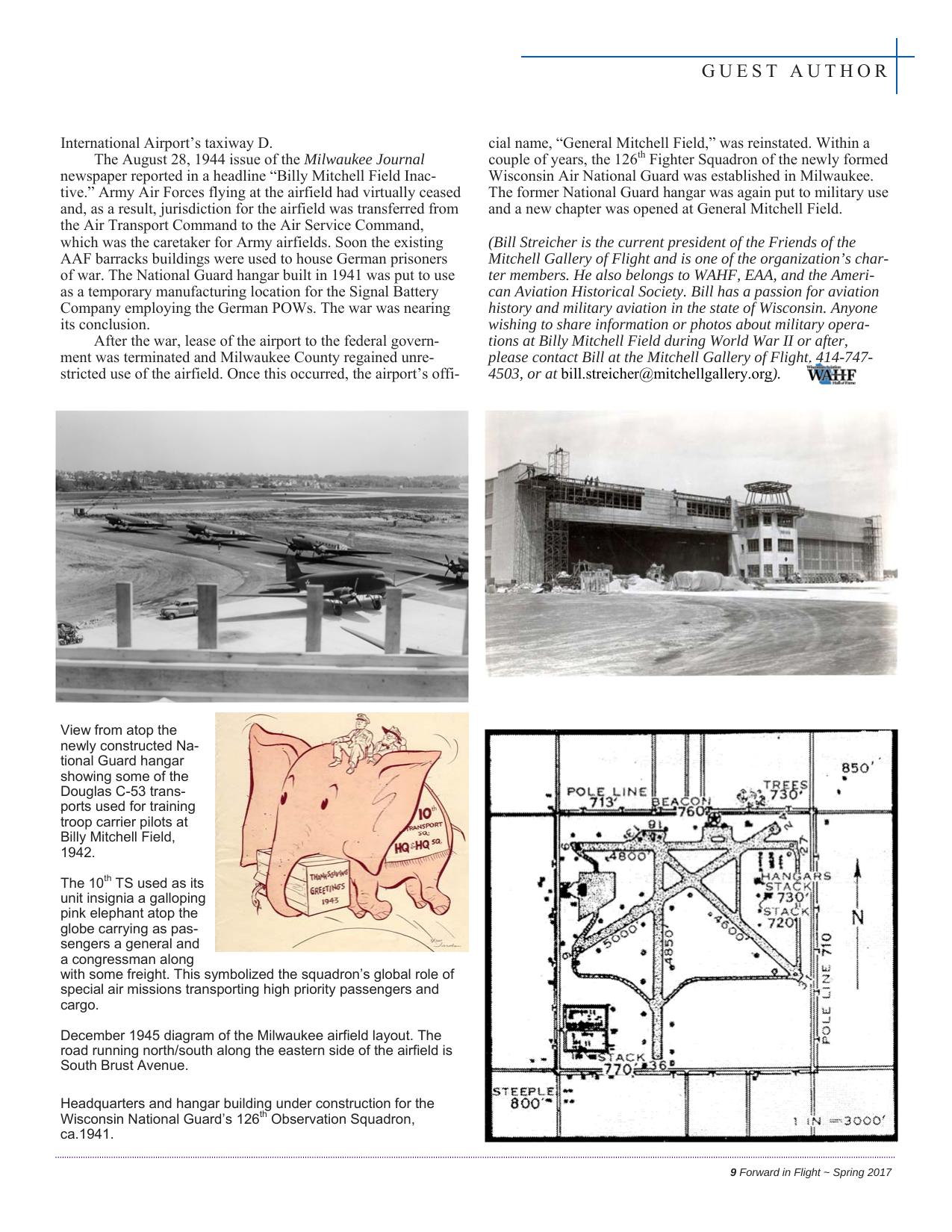

GUEST AUTHOR International Airport’s taxiway D. The August 28, 1944 issue of the Milwaukee Journal newspaper reported in a headline “Billy Mitchell Field Inactive.” Army Air Forces flying at the airfield had virtually ceased and, as a result, jurisdiction for the airfield was transferred from the Air Transport Command to the Air Service Command, which was the caretaker for Army airfields. Soon the existing AAF barracks buildings were used to house German prisoners of war. The National Guard hangar built in 1941 was put to use as a temporary manufacturing location for the Signal Battery Company employing the German POWs. The war was nearing its conclusion. After the war, lease of the airport to the federal government was terminated and Milwaukee County regained unrestricted use of the airfield. Once this occurred, the airport’s offi- cial name, “General Mitchell Field,” was reinstated. Within a couple of years, the 126th Fighter Squadron of the newly formed Wisconsin Air National Guard was established in Milwaukee. The former National Guard hangar was again put to military use and a new chapter was opened at General Mitchell Field. (Bill Streicher is the current president of the Friends of the Mitchell Gallery of Flight and is one of the organization’s charter members. He also belongs to WAHF, EAA, and the American Aviation Historical Society. Bill has a passion for aviation history and military aviation in the state of Wisconsin. Anyone wishing to share information or photos about military operations at Billy Mitchell Field during World War II or after, please contact Bill at the Mitchell Gallery of Flight, 414-7474503, or at bill.streicher@mitchellgallery.org). View from atop the newly constructed National Guard hangar showing some of the Douglas C-53 transports used for training troop carrier pilots at Billy Mitchell Field, 1942. The 10th TS used as its unit insignia a galloping pink elephant atop the globe carrying as passengers a general and a congressman along with some freight. This symbolized the squadron’s global role of special air missions transporting high priority passengers and cargo. December 1945 diagram of the Milwaukee airfield layout. The road running north/south along the eastern side of the airfield is South Brust Avenue. Headquarters and hangar building under construction for the Wisconsin National Guard’s 126th Observation Squadron, ca.1941. 9 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017

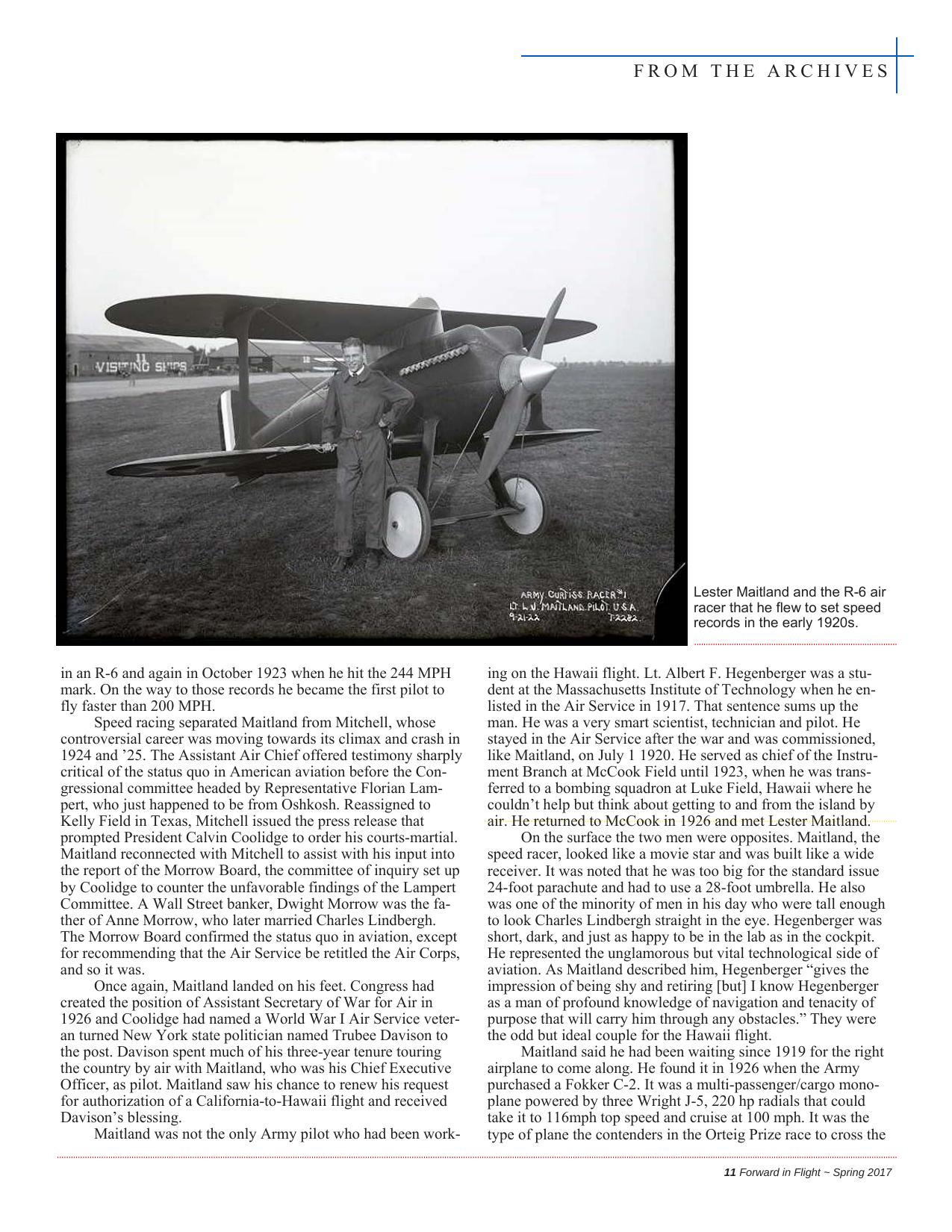

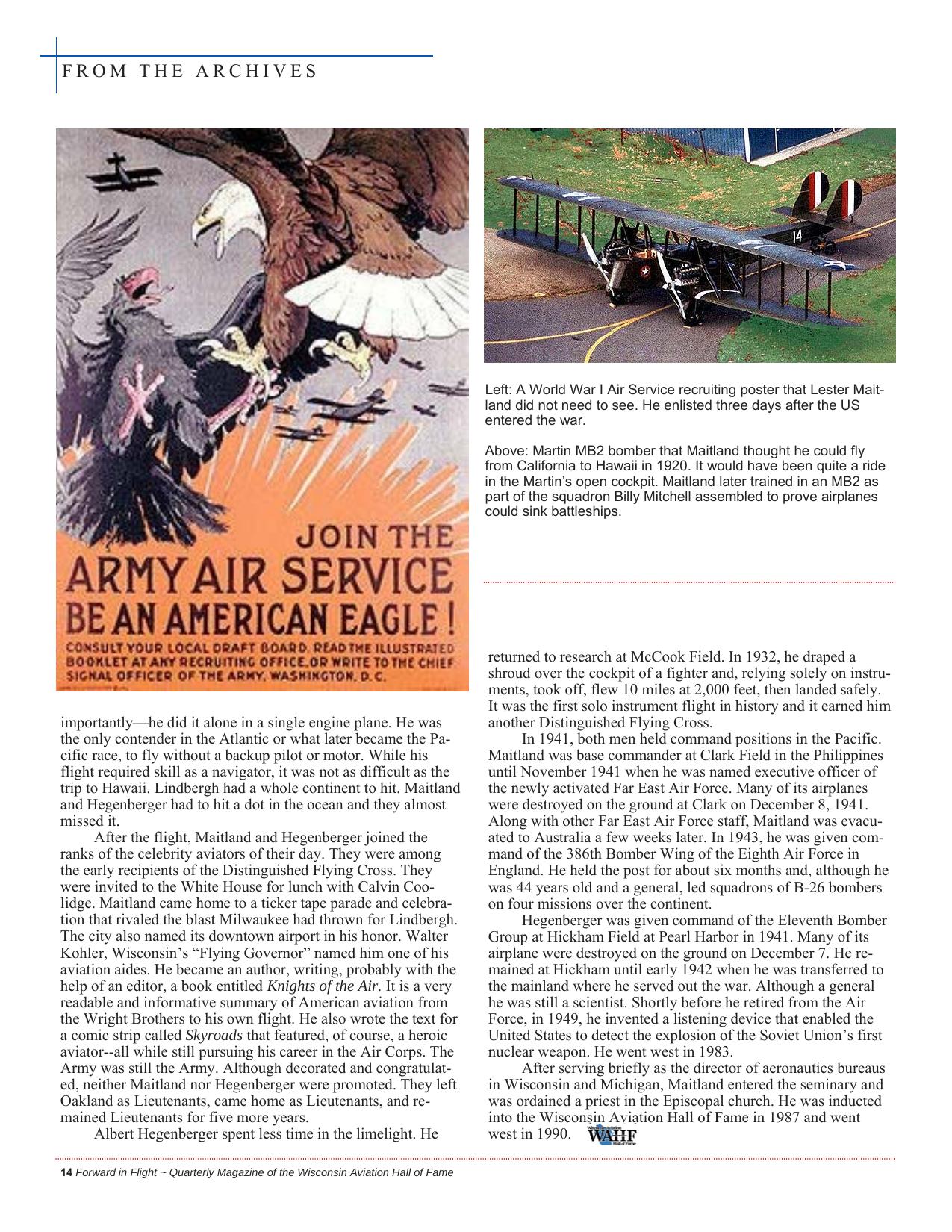

FROM THE ARCHIVES Maitland and Hegenberger From Oakland to Oahu By Michael Goc Recently I read a news article reporting that the United States Navy was training sailors to use the sextant. The centuries-old instrument that determines latitude might save the ship if all the modern, electronic navigational devices fell prey to an enemy attack, a hack, or a simple glitch. The news also made me wonder if the Navy was stowing unhackable mechanical clocks onboard since keeping accurate time is necessary to determine longitude. Maybe. I also thought of Lester Maitland. His Fokker C-2 airplane was loaded with up-to-date navigational equipment when he and co-pilot/navigator Albert F. Hegenberger made their pioneering flight across the Pacific from Oakland to Hawaii in 1927. All the new gear failed, including the whiz-bang radio direction finder, and Hegenberger had to rely on a combination of deadreckoning, observations of drift on the ocean’s surface made with a compass and, of course, a sextant, to guide the plane to its destination. Lester Maitland began the journey that would eventually take him to Hawaii on the north side of Milwaukee in 1899. A big guy with strong, handsome features, he was two months past his eighteenth birthday, when the United States entered World War I. He enlisted in the Army and qualified for flight training, even though he was not a college graduate. He completed training and was commissioned as a Reserve officer in May 1918. After a stint as a flight instructor and gunnery school trainee he was ready to go overseas but the war ended in November ’18. Nonetheless, the Army Air Service saw something in him and he saw something in the Air Service because they both decided to stick with each other. Maitland was first assigned to McCook Field in Ohio to train as a test pilot but was soon transferred to the 6th Aero Squadron in Hawaii. The World War had prompted the United States to pay more attention to aerial defense in the Pacific. The 6th had recently moved to the newly established Luke Field on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor and was equipped with war surplus DH-4s and JN-6s. Maitland was in Hawaii when Congress officially recognized the United States Air Service and his commission as a regular officer in the Army and the Air Service share the date of July 1, 1920. Not one to hide his light under a bushel, the 20-year-old Lieutenant Maitland had barely arrived in Luke Field when he submitted a proposal to his superiors to fly an airplane back to California. He thought a Martin MB2 bomber could be modified to carry the fuel for the 2,400-mile hop. At the time, no had made a comparable flight except the British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown who flew 1,900 miles from Newfoundland to Ireland in 1919. Young Maitland’s proposal didn’t get far up the Army chain, but it might have made an impression on the Assistant Chief of the Air Service, General “Billy” Mitchell. He was assembling the 1st Provisional Air Brigade, consisting of 1,000 men and 125 aircraft assigned to demonstrate the capability of aircraft in combat with naval vessels. Mitchell brought bombing squadrons flying Handley-Page, Caproni, Martin NBS, and MB2 bombers to Langley Field in Virginia, 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Left: An undated photo of the Green Bay airport, and above, a recent one, looking northeast. The odd couple, Hegenberger and Maitland, in front of the Bird of Paradise on their way to San Francisco. along with units equipped with SE-5 pursuit and DH-4 observation aircraft. All of them were stationed in the continental states, but somehow young Lt. Maitland was included and ordered back from Hawaii. The most experienced bomber pilots in the Air Service were present but none of them had ever tried to sink a naval vessel. They all had to train and practice, including Maitland, who likely logged his first hours at the control of a bomber at Langley. He was not one of the pilots whose bombs demonstrated the future of air power by sinking the naval vessels in Mitchell’s controversial demonstration but he was part of Mitchell’s Brigade and that fact opened the door to a promising future. He did not return to Hawaii. He did become part of the aerial show team that Mitchell commissioned to exhibit the potential of aviation to Americans. Endurance tests, speed races, coast-to-coast flights, and the first round-the-world flight were part of the program. Maitland became a speed racer, piloting the hot buggy of his day, the Curtiss R-6. Several pilots set speed records in the R-6, including Mitchell. Maitland became “the world’s fastest man” in March 1923 when he clocked 236 MPH Photos Courtesy National Air and Space Museum

FROM THE ARCHIVES Lester Maitland and the R-6 air racer that he flew to set speed records in the early 1920s. in an R-6 and again in October 1923 when he hit the 244 MPH mark. On the way to those records he became the first pilot to fly faster than 200 MPH. Speed racing separated Maitland from Mitchell, whose controversial career was moving towards its climax and crash in 1924 and ’25. The Assistant Air Chief offered testimony sharply critical of the status quo in American aviation before the Congressional committee headed by Representative Florian Lampert, who just happened to be from Oshkosh. Reassigned to Kelly Field in Texas, Mitchell issued the press release that prompted President Calvin Coolidge to order his courts-martial. Maitland reconnected with Mitchell to assist with his input into the report of the Morrow Board, the committee of inquiry set up by Coolidge to counter the unfavorable findings of the Lampert Committee. A Wall Street banker, Dwight Morrow was the father of Anne Morrow, who later married Charles Lindbergh. The Morrow Board confirmed the status quo in aviation, except for recommending that the Air Service be retitled the Air Corps, and so it was. Once again, Maitland landed on his feet. Congress had created the position of Assistant Secretary of War for Air in 1926 and Coolidge had named a World War I Air Service veteran turned New York state politician named Trubee Davison to the post. Davison spent much of his three-year tenure touring the country by air with Maitland, who was his Chief Executive Officer, as pilot. Maitland saw his chance to renew his request for authorization of a California-to-Hawaii flight and received Davison’s blessing. Maitland was not the only Army pilot who had been work- ing on the Hawaii flight. Lt. Albert F. Hegenberger was a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology when he enlisted in the Air Service in 1917. That sentence sums up the man. He was a very smart scientist, technician and pilot. He stayed in the Air Service after the war and was commissioned, like Maitland, on July 1 1920. He served as chief of the Instrument Branch at McCook Field until 1923, when he was transferred to a bombing squadron at Luke Field, Hawaii where he couldn’t help but think about getting to and from the island by air. He returned to McCook in 1926 and met Lester Maitland. On the surface the two men were opposites. Maitland, the speed racer, looked like a movie star and was built like a wide receiver. It was noted that he was too big for the standard issue 24-foot parachute and had to use a 28-foot umbrella. He also was one of the minority of men in his day who were tall enough to look Charles Lindbergh straight in the eye. Hegenberger was short, dark, and just as happy to be in the lab as in the cockpit. He represented the unglamorous but vital technological side of aviation. As Maitland described him, Hegenberger “gives the impression of being shy and retiring [but] I know Hegenberger as a man of profound knowledge of navigation and tenacity of purpose that will carry him through any obstacles.” They were the odd but ideal couple for the Hawaii flight. Maitland said he had been waiting since 1919 for the right airplane to come along. He found it in 1926 when the Army purchased a Fokker C-2. It was a multi-passenger/cargo monoplane powered by three Wright J-5, 220 hp radials that could take it to 116mph top speed and cruise at 100 mph. It was the type of plane the contenders in the Orteig Prize race to cross the 11 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017

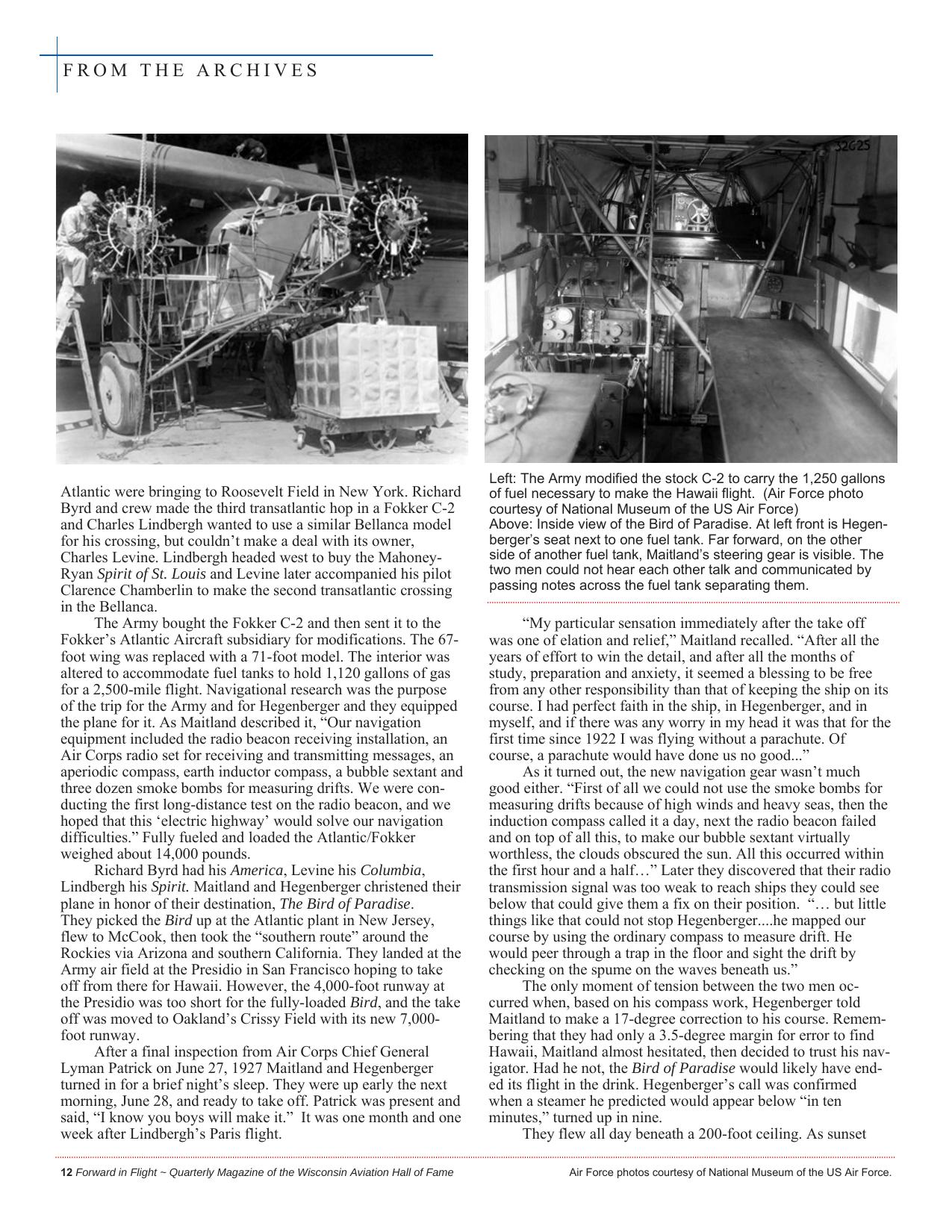

FROM THE ARCHIVES Atlantic were bringing to Roosevelt Field in New York. Richard Byrd and crew made the third transatlantic hop in a Fokker C-2 and Charles Lindbergh wanted to use a similar Bellanca model for his crossing, but couldn’t make a deal with its owner, Charles Levine. Lindbergh headed west to buy the MahoneyRyan Spirit of St. Louis and Levine later accompanied his pilot Clarence Chamberlin to make the second transatlantic crossing in the Bellanca. The Army bought the Fokker C-2 and then sent it to the Fokker’s Atlantic Aircraft subsidiary for modifications. The 67foot wing was replaced with a 71-foot model. The interior was altered to accommodate fuel tanks to hold 1,120 gallons of gas for a 2,500-mile flight. Navigational research was the purpose of the trip for the Army and for Hegenberger and they equipped the plane for it. As Maitland described it, “Our navigation equipment included the radio beacon receiving installation, an Air Corps radio set for receiving and transmitting messages, an aperiodic compass, earth inductor compass, a bubble sextant and three dozen smoke bombs for measuring drifts. We were conducting the first long-distance test on the radio beacon, and we hoped that this ‘electric highway’ would solve our navigation difficulties.” Fully fueled and loaded the Atlantic/Fokker weighed about 14,000 pounds. Richard Byrd had his America, Levine his Columbia, Lindbergh his Spirit. Maitland and Hegenberger christened their plane in honor of their destination, The Bird of Paradise. They picked the Bird up at the Atlantic plant in New Jersey, flew to McCook, then took the “southern route” around the Rockies via Arizona and southern California. They landed at the Army air field at the Presidio in San Francisco hoping to take off from there for Hawaii. However, the 4,000-foot runway at the Presidio was too short for the fully-loaded Bird, and the take off was moved to Oakland’s Crissy Field with its new 7,000foot runway. After a final inspection from Air Corps Chief General Lyman Patrick on June 27, 1927 Maitland and Hegenberger turned in for a brief night’s sleep. They were up early the next morning, June 28, and ready to take off. Patrick was present and said, “I know you boys will make it.” It was one month and one week after Lindbergh’s Paris flight. 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Left: The Army modified the stock C-2 to carry the 1,250 gallons of fuel necessary to make the Hawaii flight. (Air Force photo courtesy of National Museum of the US Air Force) Above: Inside view of the Bird of Paradise. At left front is Hegenberger’s seat next to one fuel tank. Far forward, on the other side of another fuel tank, Maitland’s steering gear is visible. The two men could not hear each other talk and communicated by passing notes across the fuel tank separating them. “My particular sensation immediately after the take off was one of elation and relief,” Maitland recalled. “After all the years of effort to win the detail, and after all the months of study, preparation and anxiety, it seemed a blessing to be free from any other responsibility than that of keeping the ship on its course. I had perfect faith in the ship, in Hegenberger, and in myself, and if there was any worry in my head it was that for the first time since 1922 I was flying without a parachute. Of course, a parachute would have done us no good...” As it turned out, the new navigation gear wasn’t much good either. “First of all we could not use the smoke bombs for measuring drifts because of high winds and heavy seas, then the induction compass called it a day, next the radio beacon failed and on top of all this, to make our bubble sextant virtually worthless, the clouds obscured the sun. All this occurred within the first hour and a half…” Later they discovered that their radio transmission signal was too weak to reach ships they could see below that could give them a fix on their position. “… but little things like that could not stop Hegenberger....he mapped our course by using the ordinary compass to measure drift. He would peer through a trap in the floor and sight the drift by checking on the spume on the waves beneath us.” The only moment of tension between the two men occurred when, based on his compass work, Hegenberger told Maitland to make a 17-degree correction to his course. Remembering that they had only a 3.5-degree margin for error to find Hawaii, Maitland almost hesitated, then decided to trust his navigator. Had he not, the Bird of Paradise would likely have ended its flight in the drink. Hegenberger’s call was confirmed when a steamer he predicted would appear below “in ten minutes,” turned up in nine. They flew all day beneath a 200-foot ceiling. As sunset Air Force photos courtesy of National Museum of the US Air Force.

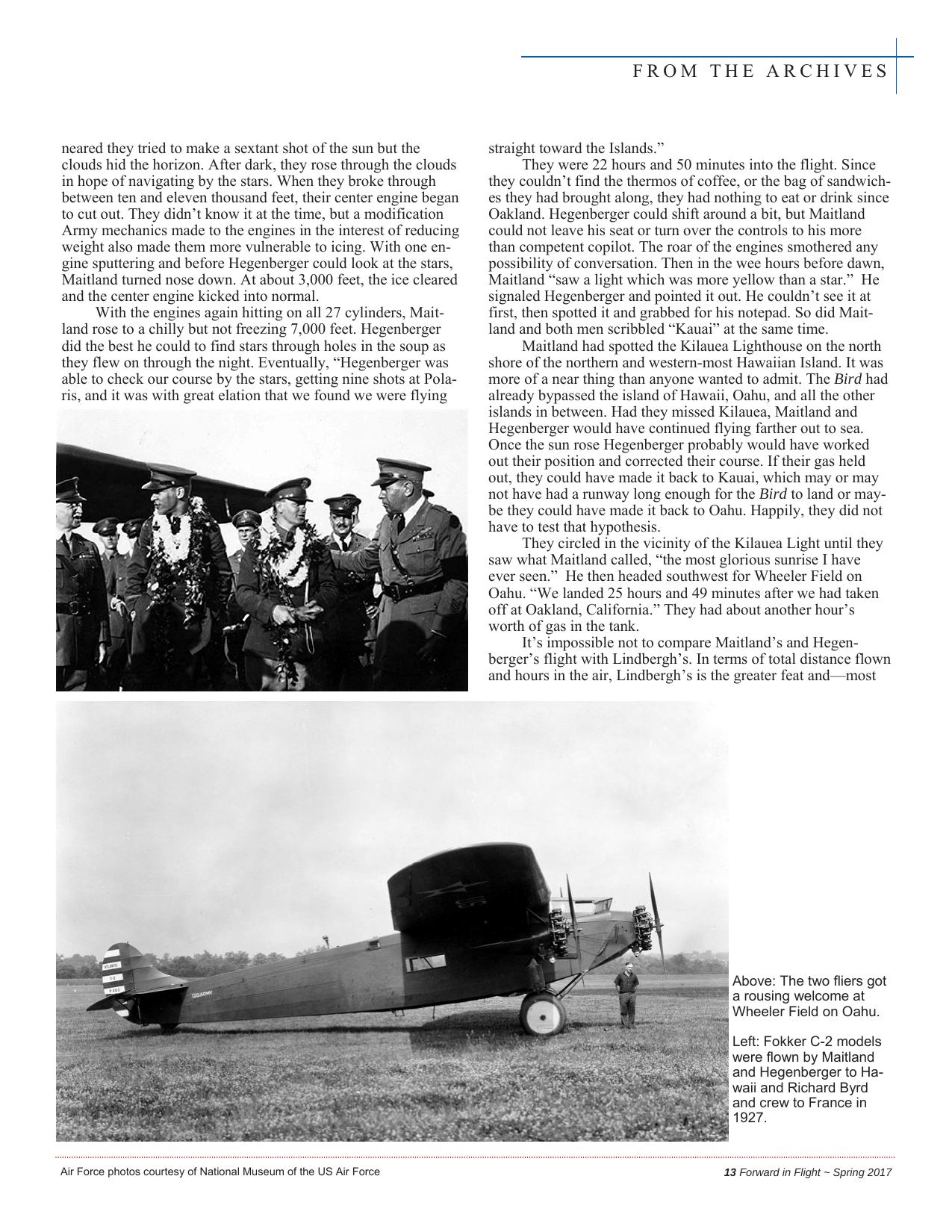

FROM THE ARCHIVES neared they tried to make a sextant shot of the sun but the clouds hid the horizon. After dark, they rose through the clouds in hope of navigating by the stars. When they broke through between ten and eleven thousand feet, their center engine began to cut out. They didn’t know it at the time, but a modification Army mechanics made to the engines in the interest of reducing weight also made them more vulnerable to icing. With one engine sputtering and before Hegenberger could look at the stars, Maitland turned nose down. At about 3,000 feet, the ice cleared and the center engine kicked into normal. With the engines again hitting on all 27 cylinders, Maitland rose to a chilly but not freezing 7,000 feet. Hegenberger did the best he could to find stars through holes in the soup as they flew on through the night. Eventually, “Hegenberger was able to check our course by the stars, getting nine shots at Polaris, and it was with great elation that we found we were flying straight toward the Islands.” They were 22 hours and 50 minutes into the flight. Since they couldn’t find the thermos of coffee, or the bag of sandwiches they had brought along, they had nothing to eat or drink since Oakland. Hegenberger could shift around a bit, but Maitland could not leave his seat or turn over the controls to his more than competent copilot. The roar of the engines smothered any possibility of conversation. Then in the wee hours before dawn, Maitland “saw a light which was more yellow than a star.” He signaled Hegenberger and pointed it out. He couldn’t see it at first, then spotted it and grabbed for his notepad. So did Maitland and both men scribbled “Kauai” at the same time. Maitland had spotted the Kilauea Lighthouse on the north shore of the northern and western-most Hawaiian Island. It was more of a near thing than anyone wanted to admit. The Bird had already bypassed the island of Hawaii, Oahu, and all the other islands in between. Had they missed Kilauea, Maitland and Hegenberger would have continued flying farther out to sea. Once the sun rose Hegenberger probably would have worked out their position and corrected their course. If their gas held out, they could have made it back to Kauai, which may or may not have had a runway long enough for the Bird to land or maybe they could have made it back to Oahu. Happily, they did not have to test that hypothesis. They circled in the vicinity of the Kilauea Light until they saw what Maitland called, “the most glorious sunrise I have ever seen.” He then headed southwest for Wheeler Field on Oahu. “We landed 25 hours and 49 minutes after we had taken off at Oakland, California.” They had about another hour’s worth of gas in the tank. It’s impossible not to compare Maitland’s and Hegenberger’s flight with Lindbergh’s. In terms of total distance flown and hours in the air, Lindbergh’s is the greater feat and—most Above: The two fliers got a rousing welcome at Wheeler Field on Oahu. Left: Fokker C-2 models were flown by Maitland and Hegenberger to Hawaii and Richard Byrd and crew to France in 1927. Air Force photos courtesy of National Museum of the US Air Force 13 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017

FROM THE ARCHIVES Left: A World War I Air Service recruiting poster that Lester Maitland did not need to see. He enlisted three days after the US entered the war. Above: Martin MB2 bomber that Maitland thought he could fly from California to Hawaii in 1920. It would have been quite a ride in the Martin’s open cockpit. Maitland later trained in an MB2 as part of the squadron Billy Mitchell assembled to prove airplanes could sink battleships. importantly—he did it alone in a single engine plane. He was the only contender in the Atlantic or what later became the Pacific race, to fly without a backup pilot or motor. While his flight required skill as a navigator, it was not as difficult as the trip to Hawaii. Lindbergh had a whole continent to hit. Maitland and Hegenberger had to hit a dot in the ocean and they almost missed it. After the flight, Maitland and Hegenberger joined the ranks of the celebrity aviators of their day. They were among the early recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross. They were invited to the White House for lunch with Calvin Coolidge. Maitland came home to a ticker tape parade and celebration that rivaled the blast Milwaukee had thrown for Lindbergh. The city also named its downtown airport in his honor. Walter Kohler, Wisconsin’s “Flying Governor” named him one of his aviation aides. He became an author, writing, probably with the help of an editor, a book entitled Knights of the Air. It is a very readable and informative summary of American aviation from the Wright Brothers to his own flight. He also wrote the text for a comic strip called Skyroads that featured, of course, a heroic aviator--all while still pursuing his career in the Air Corps. The Army was still the Army. Although decorated and congratulated, neither Maitland nor Hegenberger were promoted. They left Oakland as Lieutenants, came home as Lieutenants, and remained Lieutenants for five more years. Albert Hegenberger spent less time in the limelight. He 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame returned to research at McCook Field. In 1932, he draped a shroud over the cockpit of a fighter and, relying solely on instruments, took off, flew 10 miles at 2,000 feet, then landed safely. It was the first solo instrument flight in history and it earned him another Distinguished Flying Cross. In 1941, both men held command positions in the Pacific. Maitland was base commander at Clark Field in the Philippines until November 1941 when he was named executive officer of the newly activated Far East Air Force. Many of its airplanes were destroyed on the ground at Clark on December 8, 1941. Along with other Far East Air Force staff, Maitland was evacuated to Australia a few weeks later. In 1943, he was given command of the 386th Bomber Wing of the Eighth Air Force in England. He held the post for about six months and, although he was 44 years old and a general, led squadrons of B-26 bombers on four missions over the continent. Hegenberger was given command of the Eleventh Bomber Group at Hickham Field at Pearl Harbor in 1941. Many of its airplane were destroyed on the ground on December 7. He remained at Hickham until early 1942 when he was transferred to the mainland where he served out the war. Although a general he was still a scientist. Shortly before he retired from the Air Force, in 1949, he invented a listening device that enabled the United States to detect the explosion of the Soviet Union’s first nuclear weapon. He went west in 1983. After serving briefly as the director of aeronautics bureaus in Wisconsin and Michigan, Maitland entered the seminary and was ordained a priest in the Episcopal church. He was inducted into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame in 1987 and went west in 1990.

BOOK REVIEW Cartoons for Victory Reviewed by John Dorcey I remember fondly sitting on the floor, enjoying the color cartoon, or comic, supplement of the Sunday newspaper of my childhood. The provided smiles and values through eight pages of Beetle Bailey, Blondie, Family Circus, Nancy, Peanuts, Pogo, and Dick Tracy, among others. Little did I know at the time that my parents and others of the greatest generation experienced the same cartoon characters sharing more serious information 20 years earlier. Characters like Li’l Abner, Nancy, and Little Orphan Annie shared their views on timely subjects. Who better to encourage Americans to buy war bonds, plant Victory gardens, and save paper than our favorite cartoon characters? Many artists and animators did “their part” in the war effort stateside. Others like Bill Mauldin, Sgt, US Army; Hank Ketcham, CPO, US Navy; and Al Jaffee, Sgt, US Army Air Force provided their work while in uniform. Cartoons for Victory has been described as the most comprehensive anthology of World War II cartoons and comics ever collected. Cartoon characters during the war years told the importance of supporting our troops through necessary lifestyle changes such as rationing, recycling, and civil defense plans. Editorial positions and serious topics were also discussed via cartoons of the day. Topics seldom discussed, then or now, included the black market, internment camps, and Jim Crow, presented through the eyes and artwork of numerous artists. Cartoons for Victory, by Warren Bernard, is a large format book with more than 220 pages of cartoons; more than 90 per cent have not been seen since first published. Take a trip down memory lane and spend some time with your favorites from the funnies. I must admit it was harder to get up from the floor than it was when I was eight but the smiles were the same. 15 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017

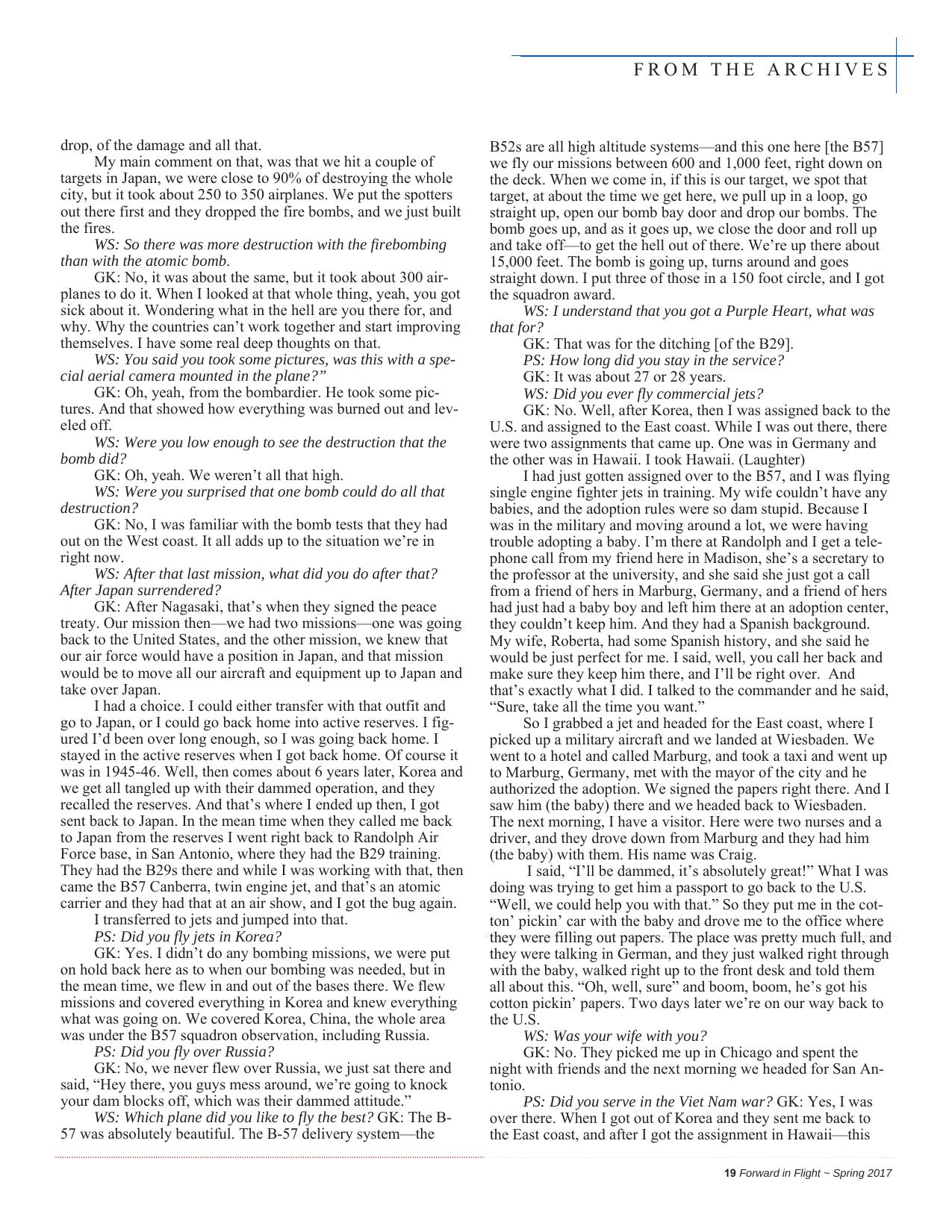

FROM THE ARCHIVES Garvin Kowalke From North Freedom to Hiroshima Edited by Michael Goc Editor’s Note: This is an edited version of an interview with Garvin Kowalke conducted by Peter Shrake and William Schuette in 2005. At the time Shrake was the executive director of the Sauk County Historical Society and Schuette was a member of the board of directors. Pete has since moved on and now works as an archivist/librarian at Circus World in Baraboo. Bill is still a very active historical society board member and community historian. Additional information on Garvin Kowalke may be found in the book “The Hero Next Door, Stories from Wisconsin's World War II Veterans,” by Kristin Gilpatrick. Her website, also called The Hero Next Door, contains stories of many Wisconsin men and women at war. We kept the original format of the interview minus quotation marks and with the speakers identified by their initials. GK: I’m Garvin Kowalke, born here in North Freedom, Wisconsin out on the farm, June 5, 1922. WS: Where did you go to school? GK: I went to a country school, right out there in Green Valley, about a three mile walk. I should say run, because I usually did it that way. I went to school there up to my 8th grade, and then started high school in North Freedom. I spent one year as a freshman. I had a real desire to be a pilot. Planes were flying over from the Dells, they came over the farm, and I just loved airplanes. [The planes from the Dells were most likely the Ryan Broughams operated by the Knaup Brothers, WAHF inductees in 2015.] We had our neighbor’s farm and he had a fire in the barn and it knocked him out so my dad bought the farm. I had to quit high school in order to help him out on the farm. So, that was the limit of my education at the time. [A few years passed], then came Pearl Harbor. Or I should say, then came my wife, Roberta, and we were married in 1940. We were there on the farm, then Pearl Harbor hit. For some reason, I said, I think I’ll go and be a pilot. So, I went to Madison and took the exam for pilot school. After I got through with the ex- am, there was a big master sergeant and he looked at my score and he said “I’ll see you in about a year.” I said “Huh?” Of course, being only a freshman, I didn’t even know what the word geometry meant. So, I completely failed the algebra, all the mathematics part of that exam. Well, being an independent individual, I stepped out the door and went to the next door. It was the enlistment center and I walked in there and I enlisted in the Army Air Corps as a private. They sent me down to boot camp in New Orleans where I took exams. I still wanted to get into the flying, my number one priority. [My instructor] indicated that my mechanics was outstanding. So, he said he’d send me to Glendale, California, to train as a crew chief on P38s. My wife and I, away we went. That trip from New Orleans out to Glendale, California, that was one of the experiences that stuck with me all throughout my life. We got on a troop train at 5:00 at night, the shades were pulled for security, and away we went. At about 5:30 in the morning, “OK, shades up,” and I pulled my shades up and the sun was just about ready to rise, and that was the picture I saw—we were just entering Arizona, and it was the most beautiful sight I’d ever seen. When we hit Glendale, I started school as a P38 crew chief. [The squadron was] due to head for Africa in a year. While I was taking my training and learning to fix engines, and stuff like that, I had a buddy—and he was a college graduate—we were real buddies, and I said I had to retake that [pilot training] exam but I couldn’t get the math. He said, “I’ll take you through a math course.” So I spent that year working on the P38s, and every night he and I sat down and we went through the books and I studied math. Then came December [1942] and I sent my wife back to Wisconsin, as I was going to be headin’ to Africa. My buddy and I went out that night and saw the girls off to Wisconsin. Then we hung around there for quite a while….I was just about able to navigate…. back to the base and crawled into the sack. Well, unfortunately, or I should say fortunately, 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame about 6:00 in the morning a trooper came in from headquarters [and he said] “Kowalke, you got to be at headquarters at 8:00 this morning to re-take your exam. The guys there, they pulled me out of the sack, took me to the shower, cooled me off, and got me dressed and everything and at 8:00 I headed in there for the exam. My mental condition: I had no worries, nothing concerned me, I was able to concentrate, so I took the exam. I never went back to redo a question, I just went one, two, three, and I went through that exam in three hours, and that was a four hour exam. I took it back to the commander and gave it to him, and he said, “I don’t think I’ll see you in another year, you’re going to be in Africa.” So he took the exam and an hour later the runner comes up, “Hey, Kowalke, you got 95 on your exam, and in one week you’re heading for camp for air cadets,” right there in Glendale. Well, that was the next step, and I went into pilot school and learned to be a pilot, on three bases in California. Then I ended up in Waco, Texas, for my final exams in 02s, which was a twin engine, and came through with flying colors. In July of ’43, hey, I’m a second lieutenant and I’m a pilot. My next assignment then—I had my application for A20’s—I wanted that twin engine attack bomber, which was really a sharp outfit. When I graduated and came up for assignment, [I got] my second choice, which was training command. Being smart, [I thought] I might as well put in a year or two getting some flying training before I get into combat. I really better know what I was doing. I went by the book and I’ve always preached that, what I had in my left hand was my Bible, what I had in my right hand was the book to run this cottin’ pickin’ operation. That was my whole position. I ended up at San Antonio, Randolph [Field] where I went through instructor’s school and then I became an instructor pilot in Waco, in advanced flying. I spent almost a year there in Waco, and during that time period we had an air show back at Randolph, and I

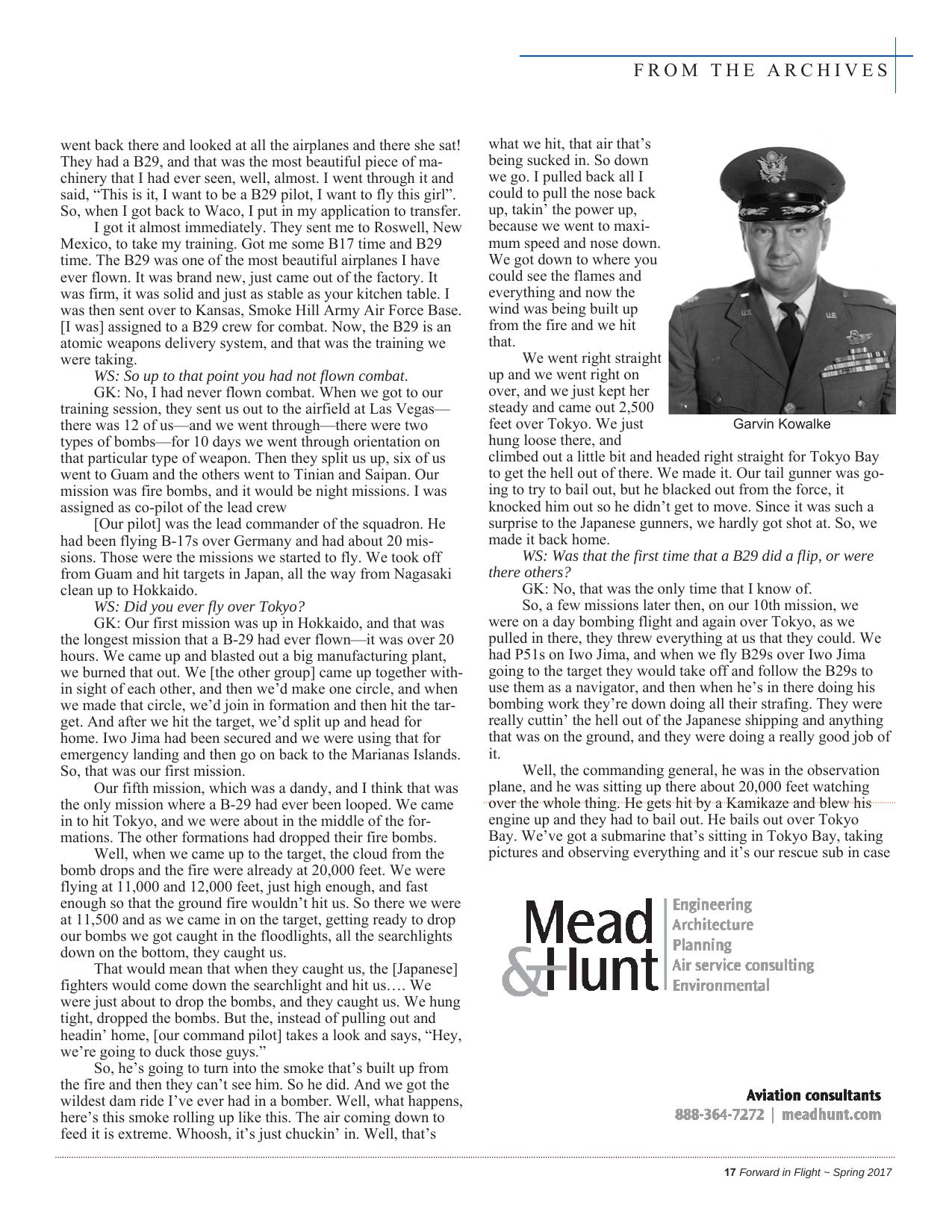

FROM THE ARCHIVES went back there and looked at all the airplanes and there she sat! They had a B29, and that was the most beautiful piece of machinery that I had ever seen, well, almost. I went through it and said, “This is it, I want to be a B29 pilot, I want to fly this girl”. So, when I got back to Waco, I put in my application to transfer. I got it almost immediately. They sent me to Roswell, New Mexico, to take my training. Got me some B17 time and B29 time. The B29 was one of the most beautiful airplanes I have ever flown. It was brand new, just came out of the factory. It was firm, it was solid and just as stable as your kitchen table. I was then sent over to Kansas, Smoke Hill Army Air Force Base. [I was] assigned to a B29 crew for combat. Now, the B29 is an atomic weapons delivery system, and that was the training we were taking. WS: So up to that point you had not flown combat. GK: No, I had never flown combat. When we got to our training session, they sent us out to the airfield at Las Vegas— there was 12 of us—and we went through—there were two types of bombs—for 10 days we went through orientation on that particular type of weapon. Then they split us up, six of us went to Guam and the others went to Tinian and Saipan. Our mission was fire bombs, and it would be night missions. I was assigned as co-pilot of the lead crew [Our pilot] was the lead commander of the squadron. He had been flying B-17s over Germany and had about 20 missions. Those were the missions we started to fly. We took off from Guam and hit targets in Japan, all the way from Nagasaki clean up to Hokkaido. WS: Did you ever fly over Tokyo? GK: Our first mission was up in Hokkaido, and that was the longest mission that a B-29 had ever flown—it was over 20 hours. We came up and blasted out a big manufacturing plant, we burned that out. We [the other group] came up together within sight of each other, and then we’d make one circle, and when we made that circle, we’d join in formation and then hit the target. And after we hit the target, we’d split up and head for home. Iwo Jima had been secured and we were using that for emergency landing and then go on back to the Marianas Islands. So, that was our first mission. Our fifth mission, which was a dandy, and I think that was the only mission where a B-29 had ever been looped. We came in to hit Tokyo, and we were about in the middle of the formations. The other formations had dropped their fire bombs. Well, when we came up to the target, the cloud from the bomb drops and the fire were already at 20,000 feet. We were flying at 11,000 and 12,000 feet, just high enough, and fast enough so that the ground fire wouldn’t hit us. So there we were at 11,500 and as we came in on the target, getting ready to drop our bombs we got caught in the floodlights, all the searchlights down on the bottom, they caught us. That would mean that when they caught us, the [Japanese] fighters would come down the searchlight and hit us…. We were just about to drop the bombs, and they caught us. We hung tight, dropped the bombs. But the, instead of pulling out and headin’ home, [our command pilot] takes a look and says, “Hey, we’re going to duck those guys.” So, he’s going to turn into the smoke that’s built up from the fire and then they can’t see him. So he did. And we got the wildest dam ride I’ve ever had in a bomber. Well, what happens, here’s this smoke rolling up like this. The air coming down to feed it is extreme. Whoosh, it’s just chuckin’ in. Well, that’s what we hit, that air that’s being sucked in. So down we go. I pulled back all I could to pull the nose back up, takin’ the power up, because we went to maximum speed and nose down. We got down to where you could see the flames and everything and now the wind was being built up from the fire and we hit that. We went right straight up and we went right on over, and we just kept her steady and came out 2,500 Garvin Kowalke feet over Tokyo. We just hung loose there, and climbed out a little bit and headed right straight for Tokyo Bay to get the hell out of there. We made it. Our tail gunner was going to try to bail out, but he blacked out from the force, it knocked him out so he didn’t get to move. Since it was such a surprise to the Japanese gunners, we hardly got shot at. So, we made it back home. WS: Was that the first time that a B29 did a flip, or were there others? GK: No, that was the only time that I know of. So, a few missions later then, on our 10th mission, we were on a day bombing flight and again over Tokyo, as we pulled in there, they threw everything at us that they could. We had P51s on Iwo Jima, and when we fly B29s over Iwo Jima going to the target they would take off and follow the B29s to use them as a navigator, and then when he’s in there doing his bombing work they’re down doing all their strafing. They were really cuttin’ the hell out of the Japanese shipping and anything that was on the ground, and they were doing a really good job of it. Well, the commanding general, he was in the observation plane, and he was sitting up there about 20,000 feet watching over the whole thing. He gets hit by a Kamikaze and blew his engine up and they had to bail out. He bails out over Tokyo Bay. We’ve got a submarine that’s sitting in Tokyo Bay, taking pictures and observing everything and it’s our rescue sub in case 17 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2017