Forward in Flight - Spring 2018

Volume 16, Issue 1 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Spring 2018

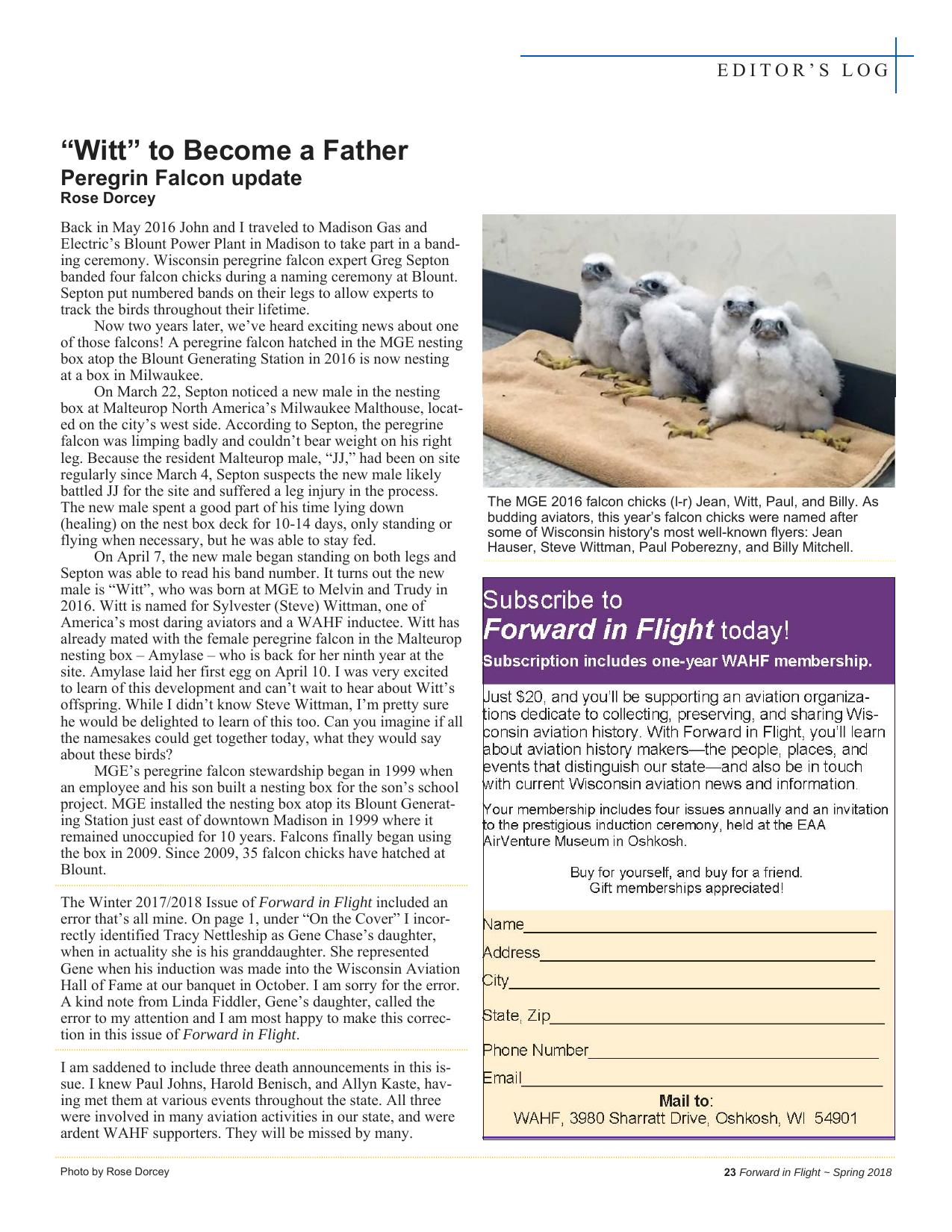

Contents Vol. 16 Issue 1/Spring 2018 A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame FLIGHT LOGS 2 Pilot for a Day The priceless value of introductory flights Elaine Kauh, CFI WE FLY 12 World War I Flight Training From the US to Canada and back again John Dorcey MEDICAL MATTERS 4 Oh for a Breath of Fresh Air Hypoxia Dr. Reid Sousek, AME TALESPINS 16 Fighter Fly-by Tom Thomas RIGHT SEAT DIARIES 6 Tips for New Students From those who have been there Dr. Heather Monthie GUEST COLUMNIST 10 Jessie G Barlow of Milwaukee Chief Yeoman, World War I John Dodds BOOK REVIEW 11 Air Force One The aircraft of the modern US presidency Reviewed by John Dorcey 19 GONE WEST Paul Johns, Harold Benisch, and Allyn Kaste ASSOCIATION NEWS 22 2018 Inductee Announcement EDITOR’s LOG 23 “Witt” to Become a Father MEMBER SPOTLIGHT 24 Eric Whyte In this issue, WAHF President Tom Thomas shares a flying experience he’ll never forget. We think you’ll enjoy it. Here’s a hint, it involves a flight in an A-37.

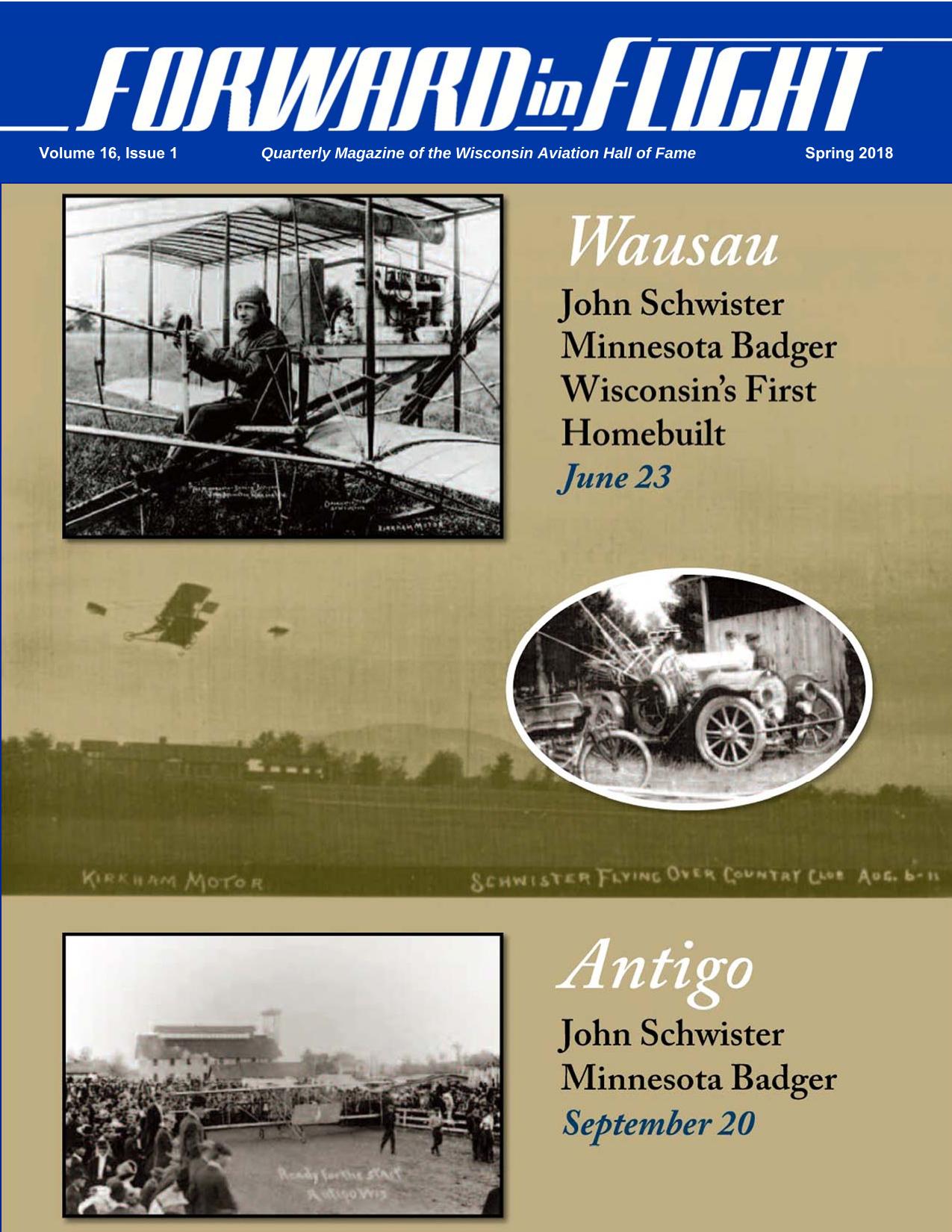

President’s Message By Tom Thomas We’ve had a cool winter season with some rollercoaster warming periods thrown in. This is Wisconsin and it’s our way. I’ve flown big, little, fast, and slow airplanes day and night through all our seasons. As they say about sailors, one should be able to sail in all seas. Similarly, aviators who fly for a living, must be able to fly in all seasons. With today’s up-to-minute weather reporting, its taken most of the guessing out of flying. Over the years forecasting has gotten better and better, but one must still remember that a forecast is just a forecast. It’s not necessarily what the weather is when you get to the airport. After over a half century of flying, one weather lesson learned was that 75 percent of the time, the weather was better than forecast when landing at the destination. About 15-20 percent of the time the weather is what it was forecast to be. But that remaining 5-10 percent of the time, it’s worse. That’s when decision making comes into play. Having alternates on your knee board, whether you’re IFR or VFR, makes life and that decision making much easier. To stay one step ahead of what’s coming, the Weather Channel gets a lot of air time back at the homestead. My children referred to it as “Dad’s Movie Channel.” In the end, the final decision comes after talking to Flight Service. Over time, every pilot becomes a meteorologist, but not every meteorologist becomes a pilot. Wrapping this up by saying ‘Fly Safe’ and don’t forget to look out the window. In the first week in March a Public Meeting was held at the Crown Plaza Hotel in Madison on East Washington Avenue. Its purpose was to discuss and obtain comments on the potential environmental impact of replacing the Madison Air Guard Unit’s F-16s with F-35s. It was well attended and driving there, I was reminded that we were in Madison. Yes, there were protesters out in front of the building with signs protesting the potential advent of the F-35. People were asked to sign in and on doing so, I noticed several fellow UW Flying Club members and members of my old Air Guard Unit in Madison. On entering it was almost like a reunion. These folks were mostly interested in aviation and wanted to learn about this new F-35 we’ve all been seeing in the media. Information tables had been set up around the room for people to learn various aspects of the potential transition. They were staffed by people who answered questions and took information from those visiting, on areas that hadn’t been covered or needed clarifications. There were tables on one side of the room where the public attending could sit down and write their thoughts, position, and questions. Drop boxes were provided for the comments. In all, it was an informative, fun experience. Meeting friends and doing a little hangar flying helped top off the meeting. If a similar venue is held in your area, discussing airport or aviation matters, don’t pass up the opportunity to make your position known. We are few, and we all need to carry the flame when given the opportunity. Forward in Flight On the cover: When we heard about the Wings Over Wausau event on May 20 at Wausau Downtown Airport we were reminded of all the great aviation history that’s been documented in Central Wisconsin. John Schwister spent the winter of 1910-11 constructing his own version of the Curtiss Model D. His MinnesotaBadger measured 32-feet nose to tail, had a 30-foot wingspan, and was powered by a 50-hp. Kirkham engine. His first flight was on June 23, 1911 in Wausau. He performed another flight in Antigo that fall. WAHF photo. The only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s events. Rose Dorcey, editor 3980 Sharratt Drive Oshkosh, WI 54901-1276 Phone: 920-279-6029 rose.dorcey@gmail.com The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. This F-35 flew daily at AirVenture 2016. Photo by Tom Thomas

FLIGHT LOGS Pilot for a Day The priceless value of introductory lessons Story and photos by Elaine Kauh It really is an act of bravery for someone who knows nothing about airplanes to get into one and fly it. He has placed his full trust in the stranger in the right seat to tell him what to do and to keep him from falling out of the sky. He has pushed to one side any misgivings, misperceptions, and unspoken fears about these mysterious machines that really do fall from the sky on occasion. He has decided to do this one thing he has always thought about doing, even just once, because it would satisfy some of that wondrous curiosity. This is the beauty of the introductory lesson. Also known as introductory flights, these mini-lessons have served as the launching point for many flying careers (mine included). They're usually set apart from airplane rides, which are just as valuable in introducing passengers and non-flyers to the world of aviation. Intro flights are designed to give a person a first-hand look at what it’s like to take the controls of a small plane and undergo a typical flight lesson. They include about 30 minutes of “ground school” to explain a few concepts prior to flying, and a similar amount of flight time. The “student” sits in the pilot’s seat and uses the flight controls while his/her instructor assists, demonstrates, and monitors from the other seat. This will count as a first lesson for anyone serious about starting pilot training, and I've had the pleasure of starting many new pilot logbooks with entries for first-time ground and flight training. The pre-flight orientation is just as important as the flight itself in getting people started on the right foot. Depending on the person and their experience with flying, I have three talking points I include in every introductory session. Each one is designed to either quell any anxieties about flying or remedy a common misunderstanding. Often, these details result in some jawdropping surprise. For instance, I'll explain that airports are everywhere and are quite different from the large, commercial-level fields we’re all familiar with. I’ll unfold the large paper navigational chart for Wisconsin and point out the hundreds of magenta dots sprinkled throughout the state. “Each one is a public-use airport that we can fly to any time we want,” I say. The look of incredulity is common, as most non-flyers are unaware that this state has more than 700 airports. I’ve talked to several longtime residents who didn’t realize that they lived just a few miles from a small general aviation airport. Another surprising fact is that most have no control towers; pilots coming and going talk to each other on the radio to manage traffic. In fact, you aren’t required to use or even have radios in most situations. Because of our familiarity with large commercial-level airports, it’s a common misconception that all airfields have towers and air traffic controllers. Most airports are city or countyowned sites with basic operations, often by or in partnership with private entities. They accommodate small personal or 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame business aircraft and rarely have congested traffic. Even when it’s relatively busy, such as on a sunny Saturday in June, everything’s on a much smaller scale. For those who are interested in learning to fly, it’s good for them to know early on that understanding radio communications and using proper arrival/departure procedures are essential components of being a pilot. I also like to draw a simple diagram of the planned flight to explain the flight path when taking off, climbing to 3,000 feet or so above the ground, practicing flying the airplane and then returning to the same spot where we took off. It helps to know that runways are on average a mile long and a bit wider than a multilane highway (many are in the range of 75 to 100 feet wide). Most are paved in asphalt or concrete. Some are grass and some are a half-mile long or less, making them even more inconspicuous. Most small airports have just one runway, or one longer paved coupled with a short grass strip. Again, they’ll often blend into the landscape so well that it’s surprising to learn how many of these landing strips exist near you. A brief overview of the upcoming flight follows this, and I’ll introduce my

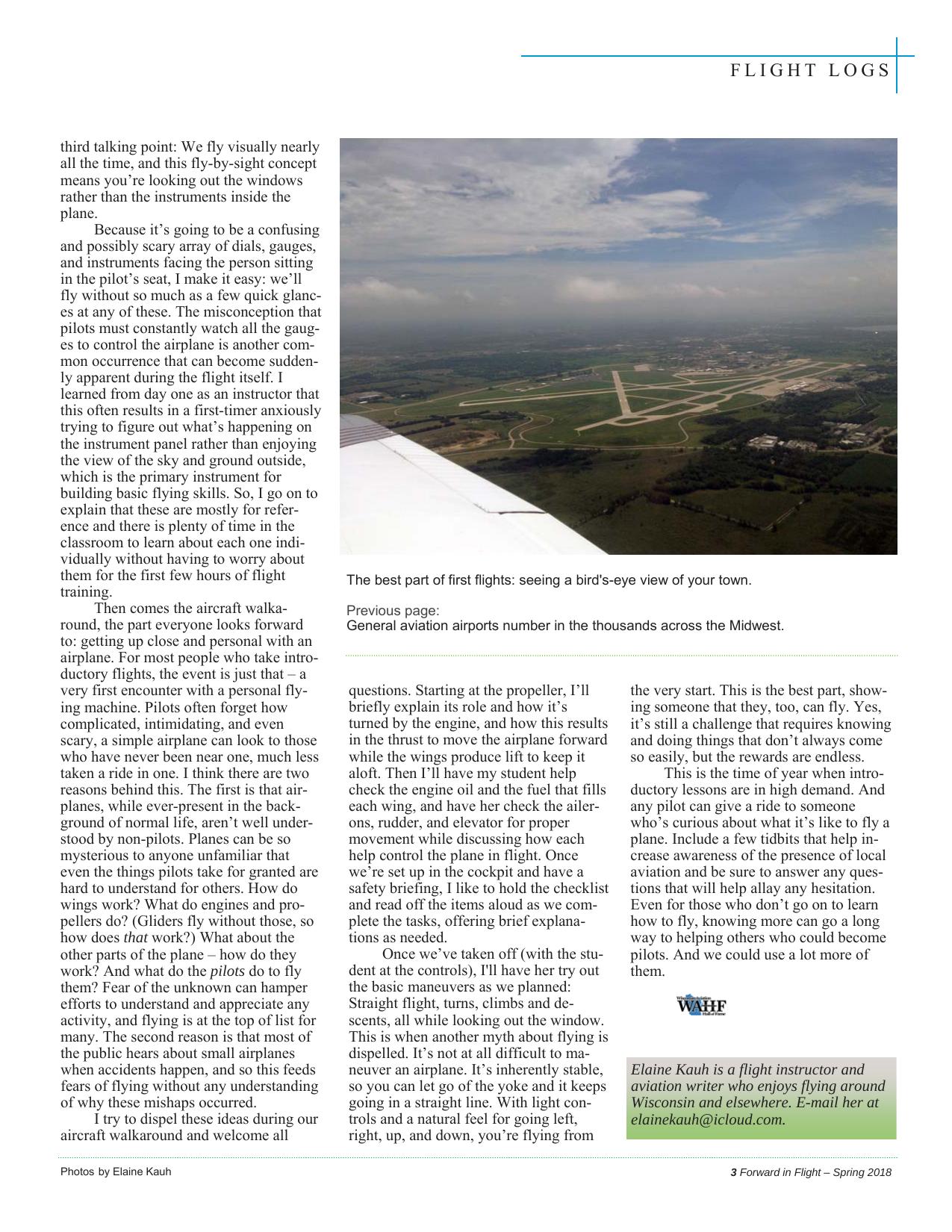

FLIGHT LOGS third talking point: We fly visually nearly all the time, and this fly-by-sight concept means you’re looking out the windows rather than the instruments inside the plane. Because it’s going to be a confusing and possibly scary array of dials, gauges, and instruments facing the person sitting in the pilot’s seat, I make it easy: we’ll fly without so much as a few quick glances at any of these. The misconception that pilots must constantly watch all the gauges to control the airplane is another common occurrence that can become suddenly apparent during the flight itself. I learned from day one as an instructor that this often results in a first-timer anxiously trying to figure out what’s happening on the instrument panel rather than enjoying the view of the sky and ground outside, which is the primary instrument for building basic flying skills. So, I go on to explain that these are mostly for reference and there is plenty of time in the classroom to learn about each one individually without having to worry about them for the first few hours of flight training. Then comes the aircraft walkaround, the part everyone looks forward to: getting up close and personal with an airplane. For most people who take introductory flights, the event is just that – a very first encounter with a personal flying machine. Pilots often forget how complicated, intimidating, and even scary, a simple airplane can look to those who have never been near one, much less taken a ride in one. I think there are two reasons behind this. The first is that airplanes, while ever-present in the background of normal life, aren’t well understood by non-pilots. Planes can be so mysterious to anyone unfamiliar that even the things pilots take for granted are hard to understand for others. How do wings work? What do engines and propellers do? (Gliders fly without those, so how does that work?) What about the other parts of the plane – how do they work? And what do the pilots do to fly them? Fear of the unknown can hamper efforts to understand and appreciate any activity, and flying is at the top of list for many. The second reason is that most of the public hears about small airplanes when accidents happen, and so this feeds fears of flying without any understanding of why these mishaps occurred. I try to dispel these ideas during our aircraft walkaround and welcome all Photos by Elaine Kauh The best part of first flights: seeing a bird's-eye view of your town. Previous page: General aviation airports number in the thousands across the Midwest. questions. Starting at the propeller, I’ll briefly explain its role and how it’s turned by the engine, and how this results in the thrust to move the airplane forward while the wings produce lift to keep it aloft. Then I’ll have my student help check the engine oil and the fuel that fills each wing, and have her check the ailerons, rudder, and elevator for proper movement while discussing how each help control the plane in flight. Once we’re set up in the cockpit and have a safety briefing, I like to hold the checklist and read off the items aloud as we complete the tasks, offering brief explanations as needed. Once we’ve taken off (with the student at the controls), I'll have her try out the basic maneuvers as we planned: Straight flight, turns, climbs and descents, all while looking out the window. This is when another myth about flying is dispelled. It’s not at all difficult to maneuver an airplane. It’s inherently stable, so you can let go of the yoke and it keeps going in a straight line. With light controls and a natural feel for going left, right, up, and down, you’re flying from the very start. This is the best part, showing someone that they, too, can fly. Yes, it’s still a challenge that requires knowing and doing things that don’t always come so easily, but the rewards are endless. This is the time of year when introductory lessons are in high demand. And any pilot can give a ride to someone who’s curious about what it’s like to fly a plane. Include a few tidbits that help increase awareness of the presence of local aviation and be sure to answer any questions that will help allay any hesitation. Even for those who don’t go on to learn how to fly, knowing more can go a long way to helping others who could become pilots. And we could use a lot more of them. Elaine Kauh is a flight instructor and aviation writer who enjoys flying around Wisconsin and elsewhere. E-mail her at elainekauh@icloud.com. 3 Forward in Flight – Spring 2018

MEDICAL MATTERS Oh for a Breath of Fresh Air Hypoxia By Dr. Reid Sousek There we were, sitting for 30 minutes in the chamber, wearing a mask, breathing oxygen. Our instructor prepared us for what to expect with a rapid decompression. The effective altitude of the chamber would suddenly rise to 25,000 feet, simulating a rapid loss of cabin pressure. The bell rang and, though we could hear, our positive pressure masks did not have microphones, so we signaled a thumbs-up when ready. Once the operator outside, received a thumbs-up from all, the chamber suddenly filled with fog, becoming dark and cold. However, within seconds, the temperature returned to normal and the fog dissipated. We were effectively now at an air pressure of around 280 mm Hg (sea level ~ 760 mm Hg). For those who prefer inches of mercury, this would be around 11.12 in. Hg (sea level ~ 29.92 in Hg.) At this point, we still had on our masks, so we were able to observe the different sensory findings of a rapid decompression. Next, we learned firsthand about the effects of hypoxia in the hopes we would recognize our own telltale signs if we ever experienced hypoxia ourselves. For this, we each had a partner sitting directly across the small chamber from us. Half the class of 12 would remove our mask and attempt to do a simple math worksheet and try to keep an eye on a 16-color wheel. The other half were able to sit back and watch the show. My partner went first, and, within about 90 seconds, he began looking around the chamber having given up on the math worksheet with only a few problems done. At around two minutes, the chamber attendant assisted him with donning his mask. After only a few breaths, his eyes seemed more focused and his gaze more focal. Most of the other individuals also needed the mask after only a few minutes. One person lasted over six minutes with his oxygen saturation dropping all the way to 62 percent before getting the mask back on, but he was the exception. Now, it was my turn. I was certain I would be able to blow that six-minute time out of the water. After all, I was younger than most of the others, didn’t smoke, ran 25-30 miles a week, and ate relatively healthily. I confidently removed my mask and started working on the math sheet. My years of schooling and test-taking took over and I completely focused all my efforts on the test at hand and forgot about the color wheel. Well, next thing I remember is seeing my mask being held in front of me and the chamber operator mimicking how to put the mask on. I clumsily fiddled with the mask and finally put it on the right way. Once again wearing the mask, I quickly became aware that I had only finished a few questions on the sheet. My partner across the chamber told me afterward I had only made it about one minute and 50 seconds before the chamber attendant came over to hand me the mask because I had been looking around the chamber absently without remembering nor seeing a thing. Apparently, I had looked at the mask for 10-15 seconds unsure what to do with it until seeing the attendant demonstrate donning the mask. I had reached my time of useful consciousness. This experience was eye-opening for me and taught the importance of being aware of the initial signs of potential hypoxia. It is not a matter of focus or willpower...I simply could not function. I likely will never fly an airplane up to 25,000 feet 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame and experience hypoxia like this as a pilot-in-command. However, many of us may fly at an altitude (especially at night) where we may get a subtly induced hypoxia. This is where the importance of hypoxia training lies. The subtle, progressive incapacitation can be just as deadly as a rapid pressure loss. A quick search of YouTube shows many videos with striking findings, with both positive and negative outcomes. Back to basics. What is hypoxia? “Hypo-” can mean low, under, below normal, down. “Ox” or “Oxi” means presence of oxygen. “-em” relates to the blood “-ia” is the fancy suffix we add to make it a condition or state. So, put these together and we have a state of low oxygen presence (hypoxia) and low oxygen presence in the blood (hypoxemia). And yes, hyperoxia (too much oxygen) is also a bad thing in some medical situations. We are worried about the partial pressure of oxygen. Air is made up of 78 percent nitrogen, 21 percent oxygen, .9 percent argon, .04 percent carbon dioxide. Dalton’s law of partial pressures states the total pressure exerted by a mixture of gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures. The contents of air are the same at sea level as they are at 25,000 feet. Oxygen makes up around 21 percent of air, so if at sea level the total air pressure is 760 mm Hg, this results in about 160mm Hg of Oxygen (760 x .21 = 160). As in every other situation, things move from high pressure to low pressure. Higher partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli of the lungs allow oxygen to move to lower pressure in the blood vessels. The opposite happens for the waste product of carbon dioxide that our body is trying to get rid of. CO2 moves from higher pressure in the vessels to lower pressure in the alveoli to be expired with each breath. Simply increasing the respiratory rate to get more air into the lungs and increase oxygen will lead to blowing off more CO2, which can have adverse effects on its own. Ways to increase oxygen transfer include either increasing the percentage of oxygen or increasing the oxygen pressure. Up to certain altitudes we can correct the oxygen deficit by simply adding supplemental oxygen and increasing the inspired oxygen above the 21 percent of “room air.” With certain very high-altitude exposures (think military), we need to also support the pressure rather than just supplement the oxygen. At the Armstrong Limit / Line (about 60,000 feet) the atmospheric pressure is so low that water will boil at human body temperature. Even breathing 100 percent oxygen at this altitude is not sufficient. Therefore, extremely high-altitude flight requires pressure suits (or pressurized capsule/cabin). In medicine, we see many different reasons for hypoxia at the tissue or end organ level. We need to have enough oxygen to inspire, get that oxygen in the lungs, get the oxygen to diffuse from the alveoli to the pulmonary capillaries and “onto” the red blood cells ...and, get it “off” the red blood cells at the correct tissues and at the proper amount. Different conditions can impact these steps in oxygen delivery. At higher altitudes, the air we are breathing can have too low of a partial pressure of oxygen, the oxygen may not be able to pass from the lungs into the bloodstream, the oxygen carrying ability of the blood may be too low, or the tissue/end organ may

MEDICAL MATTERS not be able to properly take the oxygen from the red blood cells or utilize it for metabolism properly. In aviation, all of us will be affected by decreasing oxygen pressure as we ascend in altitude. Some of us may be affected by the other stages of the delivery system depending upon our health. Hypoxia related to hypoventilation can be seen with muscular or neurologic diseases affecting the chest wall (high level cervical injury, ALS, Myasthenia Gravis, muscular dystrophy). The body is not getting air into the lungs due to the mechanics of respiration. Drug overdose leading to respiratory depression is unfortunately an increasingly frequent event caused by the misuse of opioids in our country. Opioid overuse leads to a slow or non-existent respiratory rate. Hopefully, these conditions are not a common or active issue in our aviators; but, may be something to consider with passengers. Even 100 percent oxygen is useless if we can’t get the oxygen to the tissue. Tissue hypoxia can develop with lung disease or infection. In a condition such as a Pulmonary Embolism or blood clot in the longs, there may be adequate oxygen but not appropriate blood flow to certain portions of the lung creating a ventilation-perfusion mismatch. Other lung conditions such as pneumonia, COPD, emphysema, asthma may also affect lung function and thereby lower the threshold for hypoxia. As discussed above, simply breathing faster does not always solve the problem and may exacerbate the problem. A more rapid respiratory rate will lead to breathing out more Carbon Dioxide which can cause enough symptoms to warrant its own article. Blood or oxygen carrying limitations may also lead to hypoxia. If there aren’t enough red blood cells (as in anemia) we cannot carry enough oxygen to the target cells. So, iron deficiency anemia or pernicious anemia (vitamin B12 deficiency) could also increase susceptibility to altitude/hypoxia. Simply increasing the heart rate is often not adequate to overcome these deficits because the faster the blood is pumping through the pulmonary vessels, the less time the oxygen has to diffuse from the alveoli into the blood. The hemoglobin molecule’s affinity for oxygen can also be impacted. Increasing temperature can decrease oxygenhemoglobin binding. So, a fever could increase intolerance for a hypoxic environment. Carbon Monoxide has an affinity for Hemoglobin over 200 times stronger than oxygen. So, in an oxygen poor environment, any excess carbon monoxide can be exponentially more dangerous. No matter what the reason for hypoxia, it is important to be aware of some of the signs and symptoms in yourself and FAA and AOPA photos Above: Altitude chamber at the Civil Aerospace Medical Institute, Oklahoma City. Left, wearing an aviation oxygen mask. others. Rapid breathing, cyanosis (bluish discoloration of skin), poor coordination, poor judgment are possible while other potential symptoms include headache, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, tingling, visual impairment, and even euphoria. Because each person may have varying levels of one or more of these symptoms, it is very important to pay attention to both your own, and others’, symptoms. In the altitude chamber, another training scenario includes changes to color vision. The chamber is taken from 25,000 feet down to a more moderate altitude and lights dimmed. As the mask is removed and a mildly hypoxic air is breathed, visual changes are noted. Even at a simulated 8,000-10,000 feet altitude, a color wheel, which previously had 16 differently colored wedges, blends into four quadrants of color. This illusion stops and returns to the 16 separately identifiable colors when the mask is put back on. Hypoxia also significantly affects night vision. Interestingly, for many, hearing is the last sensory input affected by hypoxia. Now, back to the breathing oxygen prior to decompression. The reason for this is to effectively purge the nitrogen portion of air from our blood stream. If this were not done, there would be a risk for nitrogen bubbles to form in our bloodstream during the decompression, which could lead to decompression sickness or the “bends.” Decompression sickness is also a reason that flying is not recommended within 12 to 24 hours of scuba diving (depending on the type of dive). Later that night, I woke up with a stabbing pain in my ears. Disoriented and confused in a dark hotel room, I sat up, momentarily unsure of what to do. Then it came to me. Earlier that day, the training staff for the altitude chamber had cautioned us that we need to remember to clear our ears regularly. The pure oxygen we had breathed, prior to the decompression, had fully distributed throughout the body...including the middle ear. That oxygen in the middle ear had diffused into tissues and the blood stream, leaving a negative pressure in the middle ear. This ear pain, more intense than I had experienced previously, resolved immediately when I cleared my ears. I was “cured” and returned to sleep and dreams of flying. Note: Review an FAA article that further explains some of these topics: https:// www.faa.gov/pilots/training/airman_education/media/IntroAviationPhys.pdf 5 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2018

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES Tips for New Students From those who have been there By Dr. Heather Monthie If you’re on the fence about learning to fly, sometimes it’s helpful to get some advice from people who are just a few steps further along than you. I’ve worked in education for a long time now and I see how helpful it is to get advice from people who are closer to where you are right now rather than people who have been doing what you want to do for the last 20 years. I’m a part of several Facebook groups to provide support, answer questions, and help educate others who are just getting started with learning to fly. Those who are just starting to learn to fly were more than willing to share their tips, advice, and ideas for those who are not too far behind them in their training. I asked the members of these groups one question, if you could give a few pieces of advice to someone who is on the fence about learning to fly, what would it be? This would be someone who has maybe taken a discovery flight, but maybe not. They might be someone who reads about what it takes to get your pilot certificate but hasn’t made the phone call yet. It might be someone who glances up to the sky when a plane flies over and thinks to themselves, “one day.” If this person is you, this article is written just for you. The responses I received are from men and women who are in the thick of their flight training. They may have already completed their first solo flight, but maybe not. They may have completed their written examination already, but maybe not. One thing in common, is that they are right smack in the middle of doing what it takes to get their pilot certificate. These are direct quotes from a few people who shared their ideas with me to share with you. Some I edited a bit for this article, but for the most part I left them intact for your encouragement! 1) It’s not a race. Just do the best you can. (Thank you, Macie!) 2) If you have a goal of flying with the airlines, but don’t know where to start, get your first-class medical certificate right away. You will want to start self-studying through all the great content that’s offered online. Then, decide what area you want to go to flight school. You want to look at different schools and decide which one fits you and your learning style the most. When looking at schools, look for your new best friend (your instructor). You will also want to work on completing the written exam, so you can focus on your actual flight training. If you ever get discouraged, take a break, think about why you wanted to do it in the first place, go back to studying and get back on track! And fly high! (Thank you, Jacquelyn!) 3) Respect Mother Nature and trust your gut instinct. It happened a couple times to me where I was in position right before takeoff and something didn’t feel right. I turned around and cancelled the flight. Never pressure yourself. (Thank you, Kelly!) 4) Before you sign up for your next lesson, go get your written done, and get your medical settled. While you’re working on completing your written and obtaining your medical, use 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame 5) 6) 7) 8) the time to interview schools and instructors so you can choose thoughtfully. Once you start flying lessons, make your flying schedule as aggressive as you can. Every day you don’t fly, your new skills will decay, especially at the start. Once a week won’t cut it; three times is better. By staying consistent each week, you will save huge amounts of time and money! (Thank you, Sara!) My advice would be to be patient and don’t get discouraged if you feel you’re not advancing quickly enough. Everyone learns in their own time and it is more important to be comfortable with the controls and maneuvers than to rush into your first solo flight. (Thank you, Alexandra!) Meet with enough instructors so that you can pick someone who will keep the process fun, who you will click with, is well organized, someone who fits with your personality, and teaches to your way of learning. (Thank you, Deanna!) If you don’t feel like you are making progress with your instructor and you feel like you don’t click, don’t be afraid to find a new one. Don’t get stressed about the things you can’t control, like bad weather. Use that downtime and put your energy into something else, like studying. (Thank you, Cindy!) You want to make sure you have your training paid in full or have the funds to be available to pay in full. If you can’t do this, fund six lessons over a two-week period and no less. Do not fund lessons one at a time as you can afford them. Approaching your lessons this way will cost you both time and money. Be professional in your approach. Look, act, and speak as if working with your instructor is the most important thing in your life for the time you are with him or her. Come prepared for your lesson. Be the sponge, ready to absorb knowledge. Insist on a pre-brief of the lesson and a debrief of the same lesson. Before every lesson be sure of what you are going to do, how you are going to do it, and what is expected to be accomplished. When you get back from the flight, find out what you did right, what you did wrong, and get a firm opinion from your instructor regard- Photos by Rose Dorcey

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES Left: Being involved in flight clubs and other groups helps keep you motivated and you’ll likely find mentors who will help you through your flight training. Previous page: Attending FAA Safety Seminars is a good way to gain extra knowledge, even when you’re not in the sky. ing how to fix it. Get a syllabus from your instructor, even if it is a Part 61 school. Use a flight simulator. Do not confine yourself to use one instructor. You may not even want to confine yourself to one flight school. Instructors leave, flight schools close, and oftentimes with no warning. Study aviation every single day for as long as you are flying. Make a commitment to excellence. Join aviation groups in real life and online. Be involved in your local flying club/ airport association. Do something with your hard-earned skills once you have your certificate. Going up to just fly around and drill holes in the air gets old after a while. When taking lessons, allow other student pilots to sit in the back seat while you are flying. Make sure they allow you to do the same. Join CAP or the USCG Auxiliary Air program and serve as an observer or aircrew. Don’t get discouraged. Getting your pilot certificate is a lesson in perseverance. Make sure you put the fact that you are a pilot on your resume. It speaks volumes about who you are and what you are capable of even to those who have no interest in aviation. (Thank you, Kevin.) 9) I did mine backwards. My husband bought a new plane. After he already had the plane, I decided to see if I could pass my medical certificate. After I completed that I went on to complete a 3-day class, never having ground school or flown a plane. I passed that and then I started flying! I still didn’t do ground school formally, but got it done. So, I did everything backwards, but am still a pilot. (Thank you, Kim.) 10) Prior to beginning flight training, I wish I had started reading and studying aeronautical knowledge. My desire to learn how to fly stemmed from a love of being in an airplane, the view from the sky and the incredible idea of being in control of an aircraft. Flight training proved to be rather overwhelming in the beginning and if I had prepared myself more efficiently before jumping into the process it would have made the initial experience less demanding. Listen to LiveATC.net as much as possible. I was terrified of speaking on the radios but listening repeatedly to my home airport transmissions on LiveATC relinquished my fears. My CFI said now I sound like a pro. (Thank you, Kimberly!) 11) There are many people holding hands out to help if you show that you’re even remotely interested in what we do. We may have training materials and old headsets we can pass on to help with the costs. Organizations like AOPA, Women in Aviation, EAA, and the Ninety-Nines all have scholarships that are relatively easy to apply for, but your initiative and your commitment, like showing up to events and volunteer opportunities, put you at the front of the line for great things! There will be concepts you may not grasp as quickly as others, but you might just be reading the wrong materials or talking with someone who can only convey the thought one way. Ask around, look at materials on YouTube. Odds are it’s the communication component in your way, not the knowledge component. It’s okay to change flight instructors if you don’t see eye-to-eye, or if you feel like you’re not getting the support you need. There are just some people you may not click with and it’s totally okay. (Thank you, Gabrie!) 12) I’m a 60-year-old who started this venture 27 years ago. I’m retired and now doing what I’ve always dreamed of doing. If there are any more like me, don’t give up, get a great instructor, and you’ll be great. I’m getting ready to solo soon. I am having a blast in my Cessna 150. (Thank you, Bonnie!) It is my hope for you that even just one of these tips from these great student pilots will help you take the next step in starting your flight training. The aviation community is extremely supportive, always willing to help, and loves to share their knowledge with others. I’d love to hear more about where you are in your flight training! Dr. Heather Monthie is an educator, speaker, author, and Certificated Flight Instructor. You can reach her at www.heathermonthie.com. 7 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2018

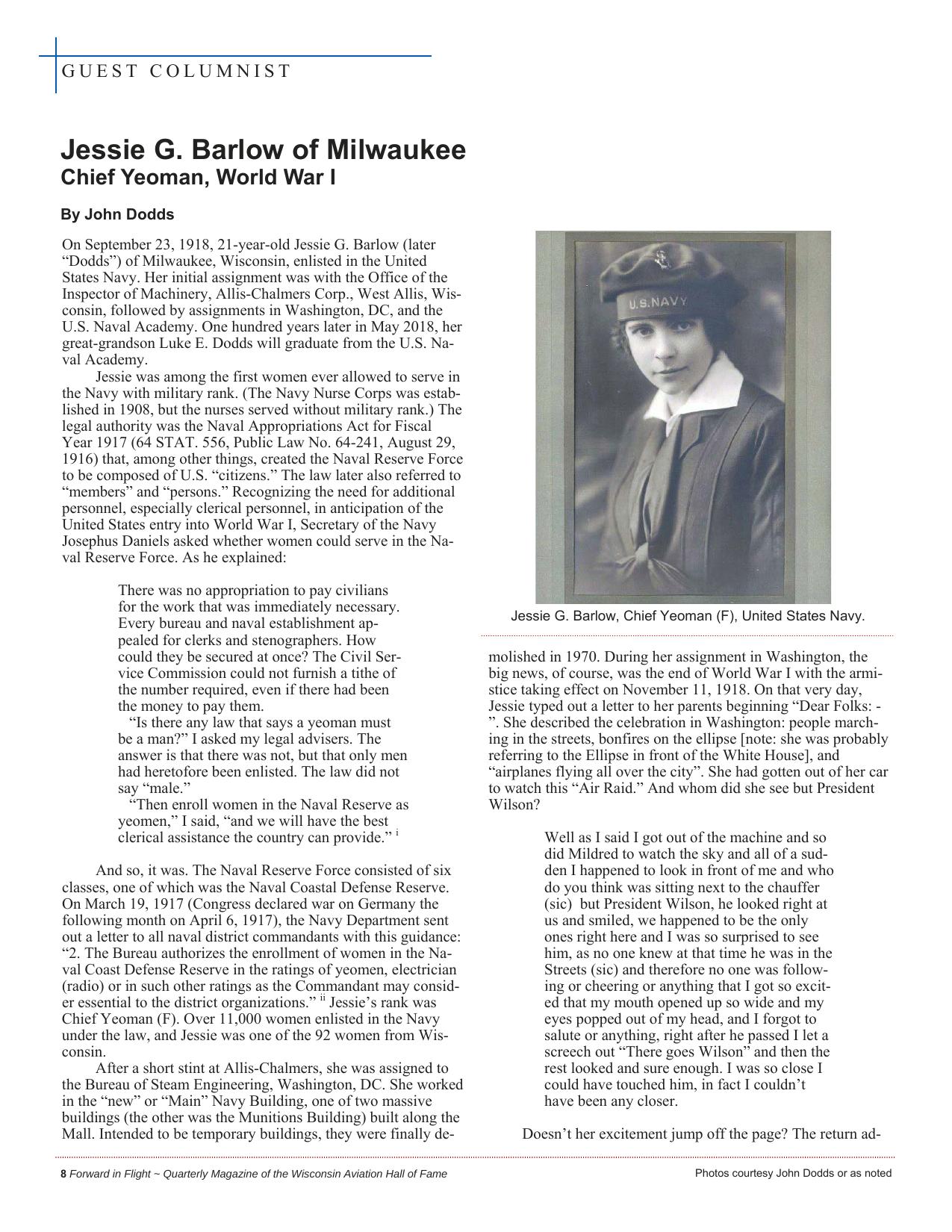

GUEST COLUMNIST Jessie G. Barlow of Milwaukee Chief Yeoman, World War I By John Dodds On September 23, 1918, 21-year-old Jessie G. Barlow (later “Dodds”) of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, enlisted in the United States Navy. Her initial assignment was with the Office of the Inspector of Machinery, Allis-Chalmers Corp., West Allis, Wisconsin, followed by assignments in Washington, DC, and the U.S. Naval Academy. One hundred years later in May 2018, her great-grandson Luke E. Dodds will graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy. Jessie was among the first women ever allowed to serve in the Navy with military rank. (The Navy Nurse Corps was established in 1908, but the nurses served without military rank.) The legal authority was the Naval Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 1917 (64 STAT. 556, Public Law No. 64-241, August 29, 1916) that, among other things, created the Naval Reserve Force to be composed of U.S. “citizens.” The law later also referred to “members” and “persons.” Recognizing the need for additional personnel, especially clerical personnel, in anticipation of the United States entry into World War I, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels asked whether women could serve in the Naval Reserve Force. As he explained: There was no appropriation to pay civilians for the work that was immediately necessary. Every bureau and naval establishment appealed for clerks and stenographers. How could they be secured at once? The Civil Service Commission could not furnish a tithe of the number required, even if there had been the money to pay them. “Is there any law that says a yeoman must be a man?” I asked my legal advisers. The answer is that there was not, but that only men had heretofore been enlisted. The law did not say “male.” “Then enroll women in the Naval Reserve as yeomen,” I said, “and we will have the best clerical assistance the country can provide.” i And so, it was. The Naval Reserve Force consisted of six classes, one of which was the Naval Coastal Defense Reserve. On March 19, 1917 (Congress declared war on Germany the following month on April 6, 1917), the Navy Department sent out a letter to all naval district commandants with this guidance: “2. The Bureau authorizes the enrollment of women in the Naval Coast Defense Reserve in the ratings of yeomen, electrician (radio) or in such other ratings as the Commandant may consider essential to the district organizations.” ii Jessie’s rank was Chief Yeoman (F). Over 11,000 women enlisted in the Navy under the law, and Jessie was one of the 92 women from Wisconsin. After a short stint at Allis-Chalmers, she was assigned to the Bureau of Steam Engineering, Washington, DC. She worked in the “new” or “Main” Navy Building, one of two massive buildings (the other was the Munitions Building) built along the Mall. Intended to be temporary buildings, they were finally de8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Jessie G. Barlow, Chief Yeoman (F), United States Navy. molished in 1970. During her assignment in Washington, the big news, of course, was the end of World War I with the armistice taking effect on November 11, 1918. On that very day, Jessie typed out a letter to her parents beginning “Dear Folks: ”. She described the celebration in Washington: people marching in the streets, bonfires on the ellipse [note: she was probably referring to the Ellipse in front of the White House], and “airplanes flying all over the city”. She had gotten out of her car to watch this “Air Raid.” And whom did she see but President Wilson? Well as I said I got out of the machine and so did Mildred to watch the sky and all of a sudden I happened to look in front of me and who do you think was sitting next to the chauffer (sic) but President Wilson, he looked right at us and smiled, we happened to be the only ones right here and I was so surprised to see him, as no one knew at that time he was in the Streets (sic) and therefore no one was following or cheering or anything that I got so excited that my mouth opened up so wide and my eyes popped out of my head, and I forgot to salute or anything, right after he passed I let a screech out “There goes Wilson” and then the rest looked and sure enough. I was so close I could have touched him, in fact I couldn’t have been any closer. Doesn’t her excitement jump off the page? The return adPhotos courtesy John Dodds or as noted

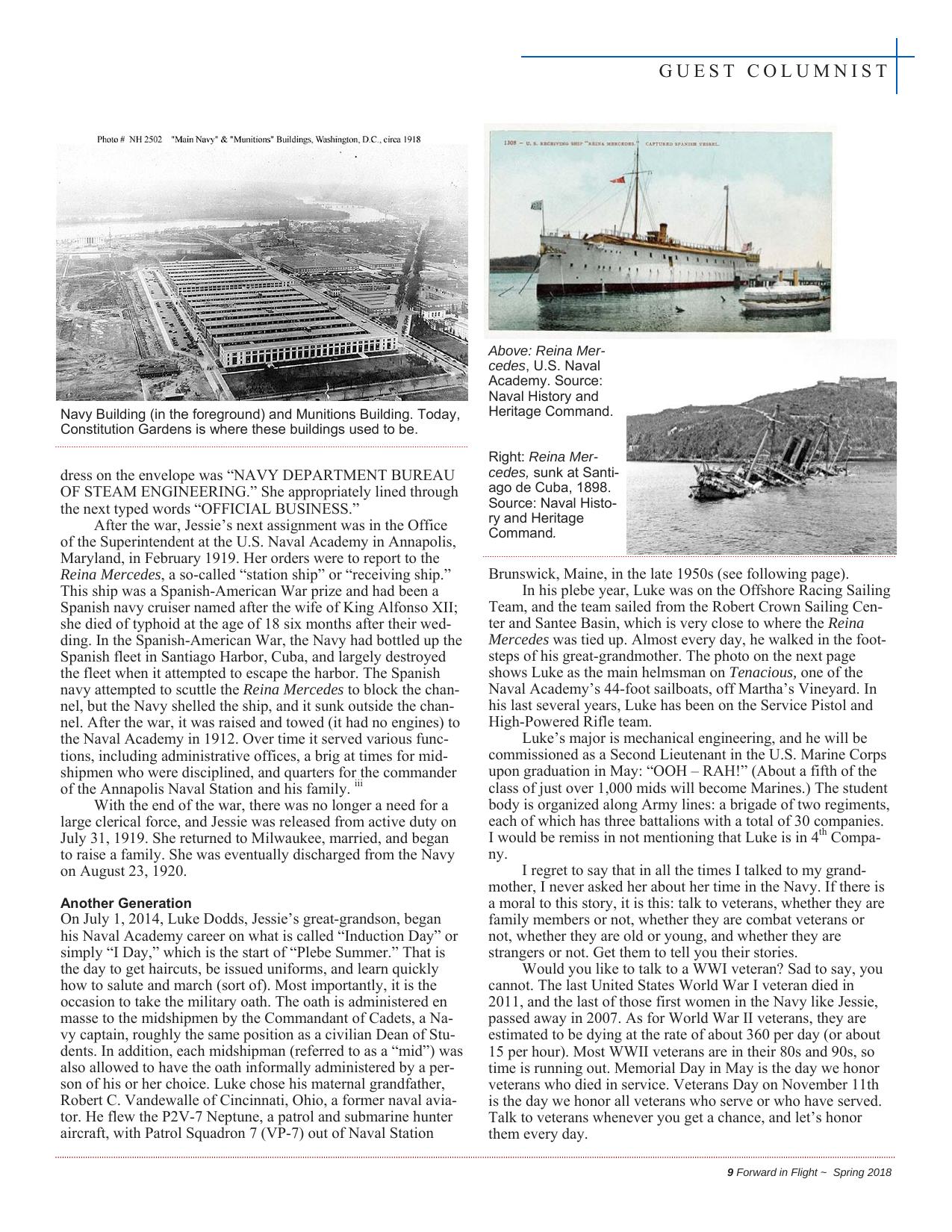

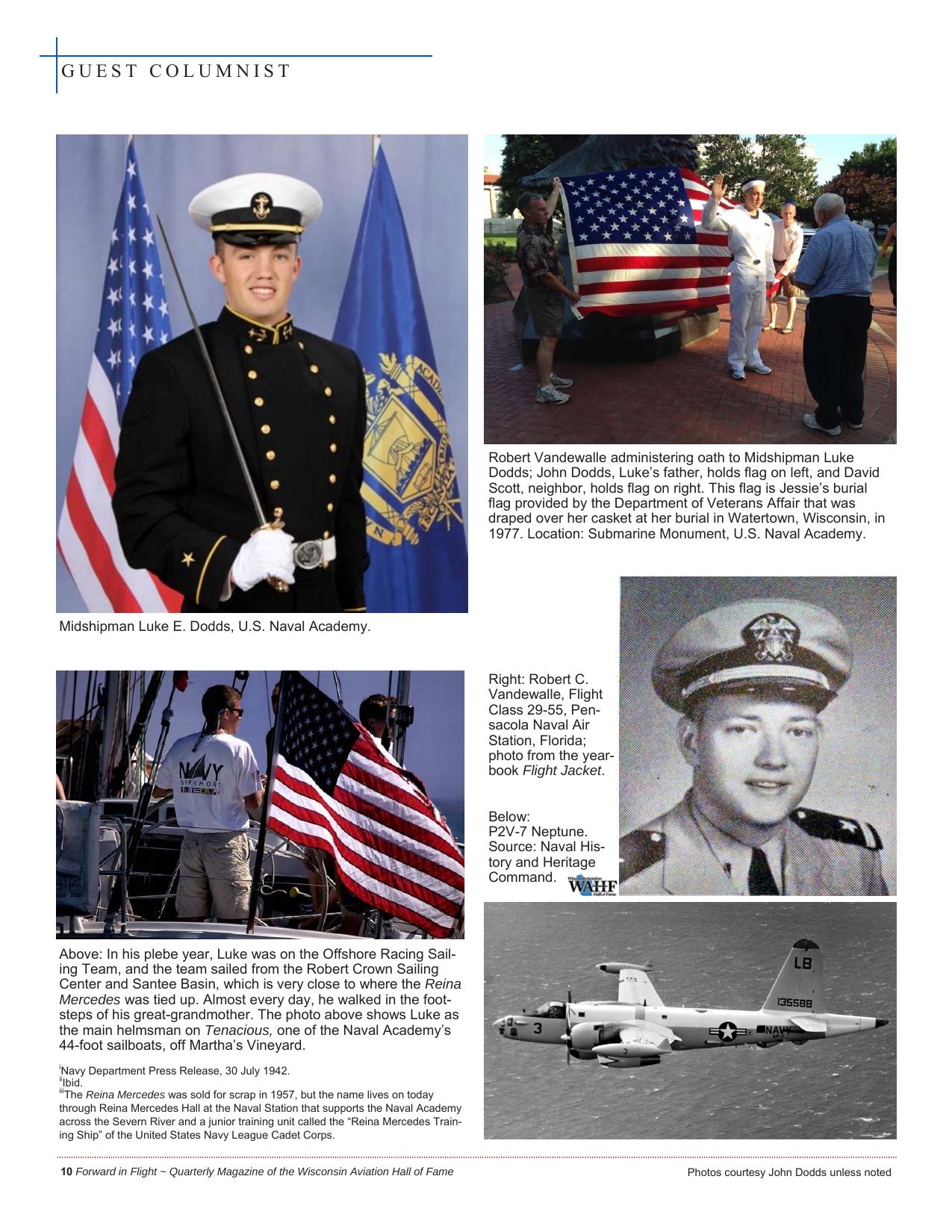

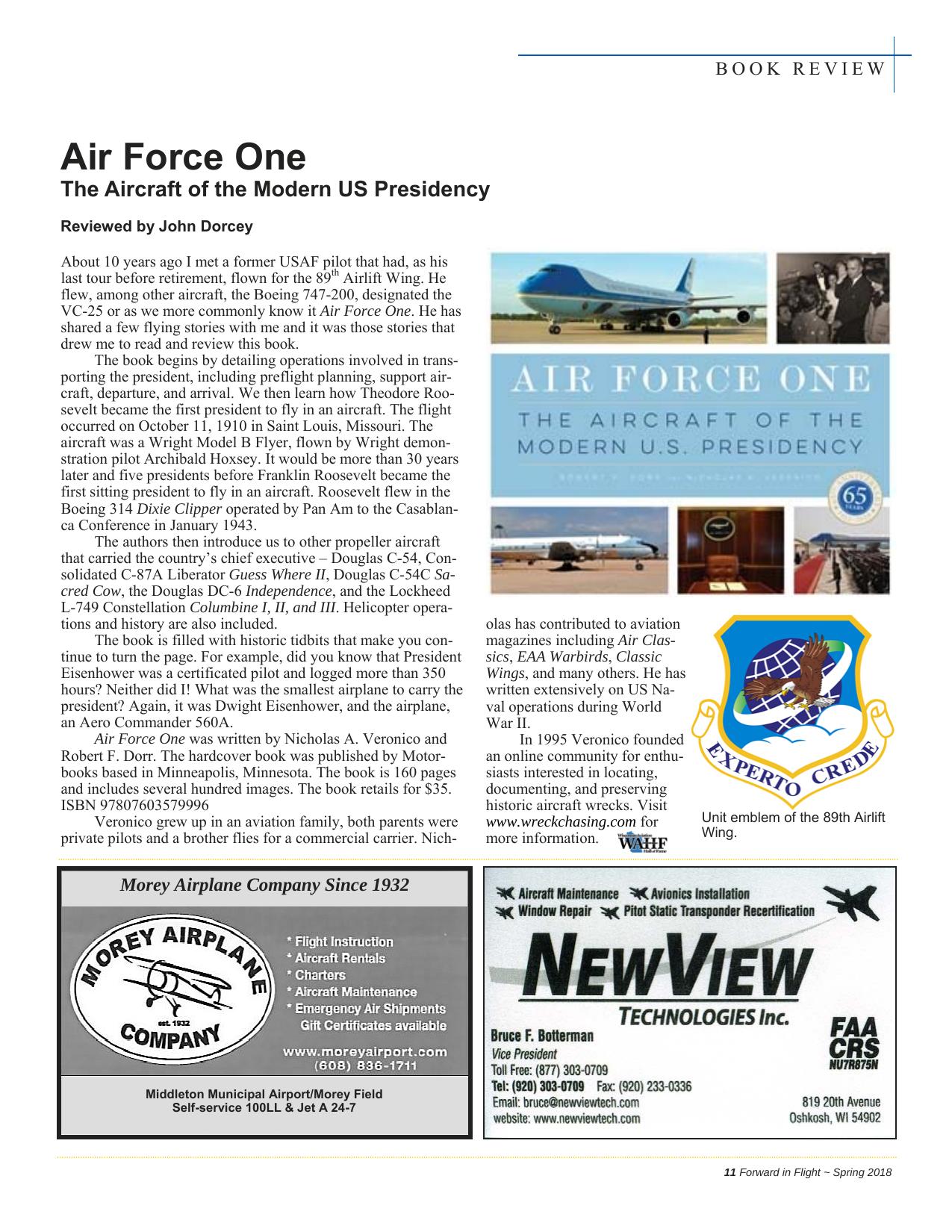

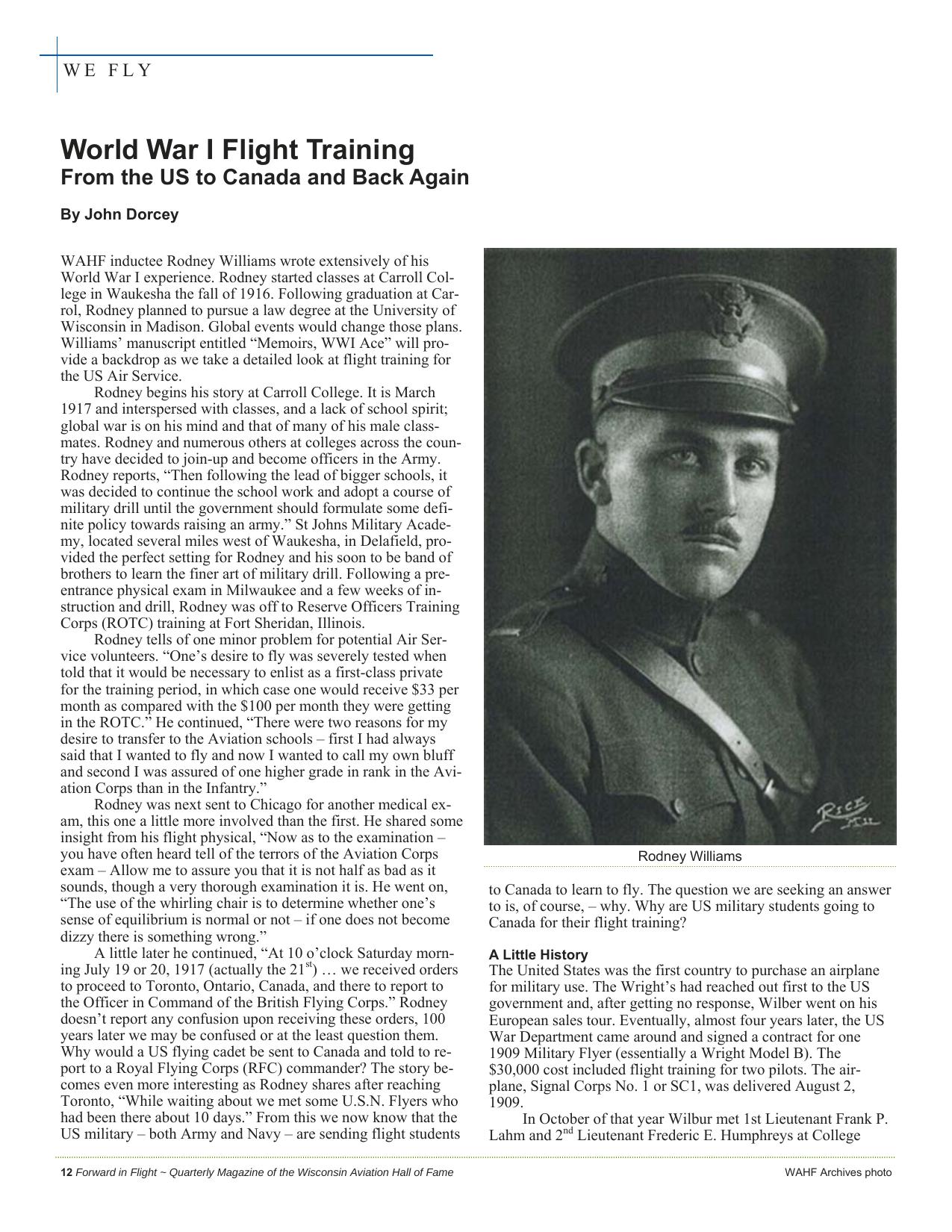

GUEST COLUMNIST Navy Building (in the foreground) and Munitions Building. Today, Constitution Gardens is where these buildings used to be. dress on the envelope was “NAVY DEPARTMENT BUREAU OF STEAM ENGINEERING.” She appropriately lined through the next typed words “OFFICIAL BUSINESS.” After the war, Jessie’s next assignment was in the Office of the Superintendent at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in February 1919. Her orders were to report to the Reina Mercedes, a so-called “station ship” or “receiving ship.” This ship was a Spanish-American War prize and had been a Spanish navy cruiser named after the wife of King Alfonso XII; she died of typhoid at the age of 18 six months after their wedding. In the Spanish-American War, the Navy had bottled up the Spanish fleet in Santiago Harbor, Cuba, and largely destroyed the fleet when it attempted to escape the harbor. The Spanish navy attempted to scuttle the Reina Mercedes to block the channel, but the Navy shelled the ship, and it sunk outside the channel. After the war, it was raised and towed (it had no engines) to the Naval Academy in 1912. Over time it served various functions, including administrative offices, a brig at times for midshipmen who were disciplined, and quarters for the commander of the Annapolis Naval Station and his family. iii With the end of the war, there was no longer a need for a large clerical force, and Jessie was released from active duty on July 31, 1919. She returned to Milwaukee, married, and began to raise a family. She was eventually discharged from the Navy on August 23, 1920. Another Generation On July 1, 2014, Luke Dodds, Jessie’s great-grandson, began his Naval Academy career on what is called “Induction Day” or simply “I Day,” which is the start of “Plebe Summer.” That is the day to get haircuts, be issued uniforms, and learn quickly how to salute and march (sort of). Most importantly, it is the occasion to take the military oath. The oath is administered en masse to the midshipmen by the Commandant of Cadets, a Navy captain, roughly the same position as a civilian Dean of Students. In addition, each midshipman (referred to as a “mid”) was also allowed to have the oath informally administered by a person of his or her choice. Luke chose his maternal grandfather, Robert C. Vandewalle of Cincinnati, Ohio, a former naval aviator. He flew the P2V-7 Neptune, a patrol and submarine hunter aircraft, with Patrol Squadron 7 (VP-7) out of Naval Station Above: Reina Mercedes, U.S. Naval Academy. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command. Right: Reina Mercedes, sunk at Santiago de Cuba, 1898. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command. Brunswick, Maine, in the late 1950s (see following page). In his plebe year, Luke was on the Offshore Racing Sailing Team, and the team sailed from the Robert Crown Sailing Center and Santee Basin, which is very close to where the Reina Mercedes was tied up. Almost every day, he walked in the footsteps of his great-grandmother. The photo on the next page shows Luke as the main helmsman on Tenacious, one of the Naval Academy’s 44-foot sailboats, off Martha’s Vineyard. In his last several years, Luke has been on the Service Pistol and High-Powered Rifle team. Luke’s major is mechanical engineering, and he will be commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps upon graduation in May: “OOH – RAH!” (About a fifth of the class of just over 1,000 mids will become Marines.) The student body is organized along Army lines: a brigade of two regiments, each of which has three battalions with a total of 30 companies. I would be remiss in not mentioning that Luke is in 4th Company. I regret to say that in all the times I talked to my grandmother, I never asked her about her time in the Navy. If there is a moral to this story, it is this: talk to veterans, whether they are family members or not, whether they are combat veterans or not, whether they are old or young, and whether they are strangers or not. Get them to tell you their stories. Would you like to talk to a WWI veteran? Sad to say, you cannot. The last United States World War I veteran died in 2011, and the last of those first women in the Navy like Jessie, passed away in 2007. As for World War II veterans, they are estimated to be dying at the rate of about 360 per day (or about 15 per hour). Most WWII veterans are in their 80s and 90s, so time is running out. Memorial Day in May is the day we honor veterans who died in service. Veterans Day on November 11th is the day we honor all veterans who serve or who have served. Talk to veterans whenever you get a chance, and let’s honor them every day. 9 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2018

GUEST COLUMNIST Robert Vandewalle administering oath to Midshipman Luke Dodds; John Dodds, Luke’s father, holds flag on left, and David Scott, neighbor, holds flag on right. This flag is Jessie’s burial flag provided by the Department of Veterans Affair that was draped over her casket at her burial in Watertown, Wisconsin, in 1977. Location: Submarine Monument, U.S. Naval Academy. Midshipman Luke E. Dodds, U.S. Naval Academy. Right: Robert C. Vandewalle, Flight Class 29-55, Pensacola Naval Air Station, Florida; photo from the yearbook Flight Jacket. Below: P2V-7 Neptune. Source: Naval History and Heritage Command. Above: In his plebe year, Luke was on the Offshore Racing Sailing Team, and the team sailed from the Robert Crown Sailing Center and Santee Basin, which is very close to where the Reina Mercedes was tied up. Almost every day, he walked in the footsteps of his great-grandmother. The photo above shows Luke as the main helmsman on Tenacious, one of the Naval Academy’s 44-foot sailboats, off Martha’s Vineyard. i Navy Department Press Release, 30 July 1942. Ibid. The Reina Mercedes was sold for scrap in 1957, but the name lives on today through Reina Mercedes Hall at the Naval Station that supports the Naval Academy across the Severn River and a junior training unit called the “Reina Mercedes Training Ship” of the United States Navy League Cadet Corps. ii iii 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Photos courtesy John Dodds unless noted

BOOK REVIEW Air Force One The Aircraft of the Modern US Presidency Reviewed by John Dorcey About 10 years ago I met a former USAF pilot that had, as his last tour before retirement, flown for the 89th Airlift Wing. He flew, among other aircraft, the Boeing 747-200, designated the VC-25 or as we more commonly know it Air Force One. He has shared a few flying stories with me and it was those stories that drew me to read and review this book. The book begins by detailing operations involved in transporting the president, including preflight planning, support aircraft, departure, and arrival. We then learn how Theodore Roosevelt became the first president to fly in an aircraft. The flight occurred on October 11, 1910 in Saint Louis, Missouri. The aircraft was a Wright Model B Flyer, flown by Wright demonstration pilot Archibald Hoxsey. It would be more than 30 years later and five presidents before Franklin Roosevelt became the first sitting president to fly in an aircraft. Roosevelt flew in the Boeing 314 Dixie Clipper operated by Pan Am to the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. The authors then introduce us to other propeller aircraft that carried the country’s chief executive – Douglas C-54, Consolidated C-87A Liberator Guess Where II, Douglas C-54C Sacred Cow, the Douglas DC-6 Independence, and the Lockheed L-749 Constellation Columbine I, II, and III. Helicopter operations and history are also included. The book is filled with historic tidbits that make you continue to turn the page. For example, did you know that President Eisenhower was a certificated pilot and logged more than 350 hours? Neither did I! What was the smallest airplane to carry the president? Again, it was Dwight Eisenhower, and the airplane, an Aero Commander 560A. Air Force One was written by Nicholas A. Veronico and Robert F. Dorr. The hardcover book was published by Motorbooks based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The book is 160 pages and includes several hundred images. The book retails for $35. ISBN 97807603579996 Veronico grew up in an aviation family, both parents were private pilots and a brother flies for a commercial carrier. Nich- olas has contributed to aviation magazines including Air Classics, EAA Warbirds, Classic Wings, and many others. He has written extensively on US Naval operations during World War II. In 1995 Veronico founded an online community for enthusiasts interested in locating, documenting, and preserving historic aircraft wrecks. Visit www.wreckchasing.com for more information. Unit emblem of the 89th Airlift Wing. Morey Airplane Company Since 1932 Middleton Municipal Airport/Morey Field Self-service 100LL & Jet A 24-7 11 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2018

WE FLY World War I Flight Training From the US to Canada and Back Again By John Dorcey WAHF inductee Rodney Williams wrote extensively of his World War I experience. Rodney started classes at Carroll College in Waukesha the fall of 1916. Following graduation at Carrol, Rodney planned to pursue a law degree at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Global events would change those plans. Williams’ manuscript entitled “Memoirs, WWI Ace” will provide a backdrop as we take a detailed look at flight training for the US Air Service. Rodney begins his story at Carroll College. It is March 1917 and interspersed with classes, and a lack of school spirit; global war is on his mind and that of many of his male classmates. Rodney and numerous others at colleges across the country have decided to join-up and become officers in the Army. Rodney reports, “Then following the lead of bigger schools, it was decided to continue the school work and adopt a course of military drill until the government should formulate some definite policy towards raising an army.” St Johns Military Academy, located several miles west of Waukesha, in Delafield, provided the perfect setting for Rodney and his soon to be band of brothers to learn the finer art of military drill. Following a preentrance physical exam in Milwaukee and a few weeks of instruction and drill, Rodney was off to Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) training at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. Rodney tells of one minor problem for potential Air Service volunteers. “One’s desire to fly was severely tested when told that it would be necessary to enlist as a first-class private for the training period, in which case one would receive $33 per month as compared with the $100 per month they were getting in the ROTC.” He continued, “There were two reasons for my desire to transfer to the Aviation schools – first I had always said that I wanted to fly and now I wanted to call my own bluff and second I was assured of one higher grade in rank in the Aviation Corps than in the Infantry.” Rodney was next sent to Chicago for another medical exam, this one a little more involved than the first. He shared some insight from his flight physical, “Now as to the examination – you have often heard tell of the terrors of the Aviation Corps exam – Allow me to assure you that it is not half as bad as it sounds, though a very thorough examination it is. He went on, “The use of the whirling chair is to determine whether one’s sense of equilibrium is normal or not – if one does not become dizzy there is something wrong.” A little later he continued, “At 10 o’clock Saturday morning July 19 or 20, 1917 (actually the 21st) … we received orders to proceed to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and there to report to the Officer in Command of the British Flying Corps.” Rodney doesn’t report any confusion upon receiving these orders, 100 years later we may be confused or at the least question them. Why would a US flying cadet be sent to Canada and told to report to a Royal Flying Corps (RFC) commander? The story becomes even more interesting as Rodney shares after reaching Toronto, “While waiting about we met some U.S.N. Flyers who had been there about 10 days.” From this we now know that the US military – both Army and Navy – are sending flight students 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Rodney Williams to Canada to learn to fly. The question we are seeking an answer to is, of course, – why. Why are US military students going to Canada for their flight training? A Little History The United States was the first country to purchase an airplane for military use. The Wright’s had reached out first to the US government and, after getting no response, Wilber went on his European sales tour. Eventually, almost four years later, the US War Department came around and signed a contract for one 1909 Military Flyer (essentially a Wright Model B). The $30,000 cost included flight training for two pilots. The airplane, Signal Corps No. 1 or SC1, was delivered August 2, 1909. In October of that year Wilbur met 1st Lieutenant Frank P. Lahm and 2nd Lieutenant Frederic E. Humphreys at College WAHF Archives photo

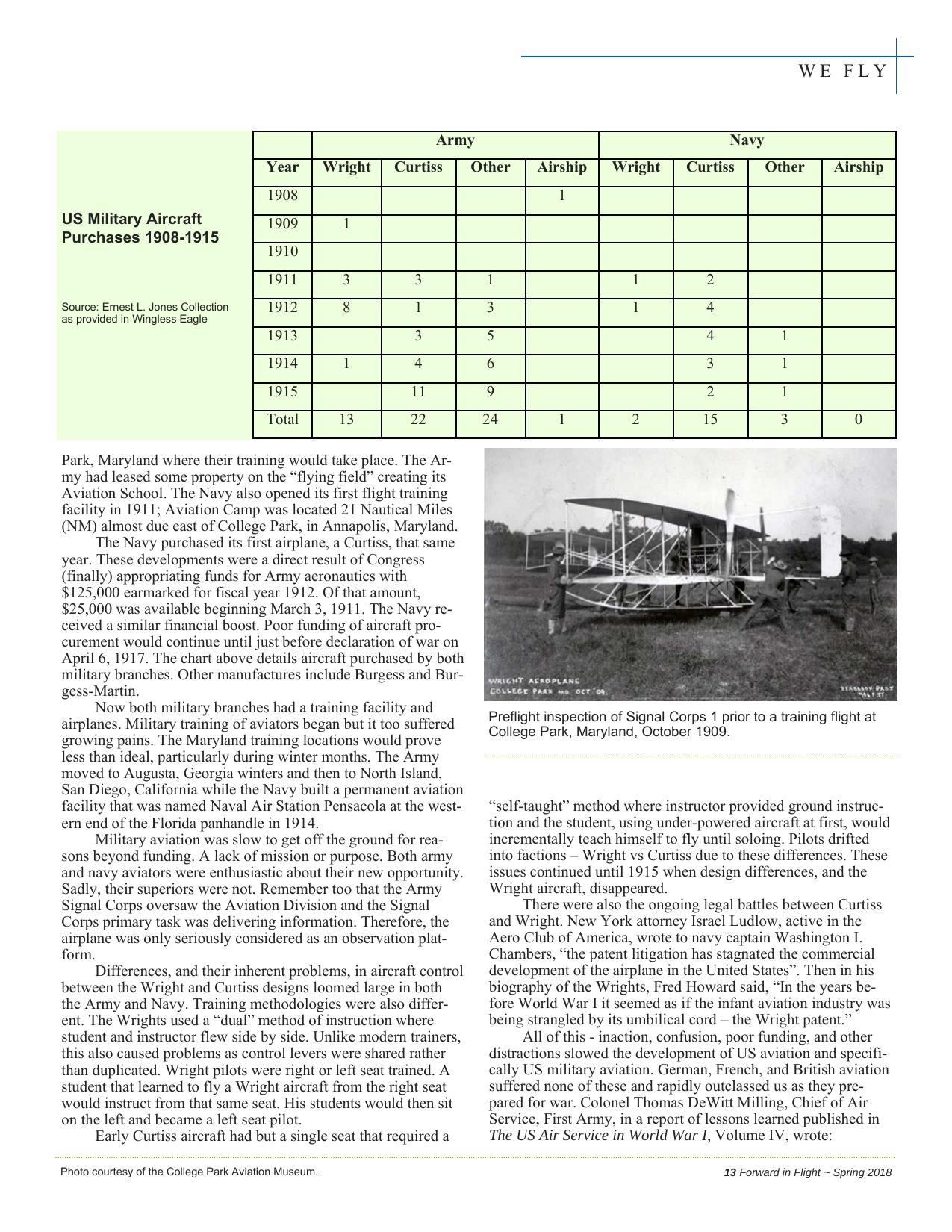

WE FLY Army Year Wright Curtiss Navy Other 1908 US Military Aircraft Purchases 1908-1915 Source: Ernest L. Jones Collection as provided in Wingless Eagle 1909 Airship Wright Curtiss Other Airship 1 1 1910 1911 3 3 1 1 2 1912 8 1 3 1 4 3 5 4 1 4 6 3 1 11 9 2 1 22 24 15 3 1913 1914 1 1915 Total 13 Park, Maryland where their training would take place. The Army had leased some property on the “flying field” creating its Aviation School. The Navy also opened its first flight training facility in 1911; Aviation Camp was located 21 Nautical Miles (NM) almost due east of College Park, in Annapolis, Maryland. The Navy purchased its first airplane, a Curtiss, that same year. These developments were a direct result of Congress (finally) appropriating funds for Army aeronautics with $125,000 earmarked for fiscal year 1912. Of that amount, $25,000 was available beginning March 3, 1911. The Navy received a similar financial boost. Poor funding of aircraft procurement would continue until just before declaration of war on April 6, 1917. The chart above details aircraft purchased by both military branches. Other manufactures include Burgess and Burgess-Martin. Now both military branches had a training facility and airplanes. Military training of aviators began but it too suffered growing pains. The Maryland training locations would prove less than ideal, particularly during winter months. The Army moved to Augusta, Georgia winters and then to North Island, San Diego, California while the Navy built a permanent aviation facility that was named Naval Air Station Pensacola at the western end of the Florida panhandle in 1914. Military aviation was slow to get off the ground for reasons beyond funding. A lack of mission or purpose. Both army and navy aviators were enthusiastic about their new opportunity. Sadly, their superiors were not. Remember too that the Army Signal Corps oversaw the Aviation Division and the Signal Corps primary task was delivering information. Therefore, the airplane was only seriously considered as an observation platform. Differences, and their inherent problems, in aircraft control between the Wright and Curtiss designs loomed large in both the Army and Navy. Training methodologies were also different. The Wrights used a “dual” method of instruction where student and instructor flew side by side. Unlike modern trainers, this also caused problems as control levers were shared rather than duplicated. Wright pilots were right or left seat trained. A student that learned to fly a Wright aircraft from the right seat would instruct from that same seat. His students would then sit on the left and became a left seat pilot. Early Curtiss aircraft had but a single seat that required a Photo courtesy of the College Park Aviation Museum. 1 2 0 Preflight inspection of Signal Corps 1 prior to a training flight at College Park, Maryland, October 1909. “self-taught” method where instructor provided ground instruction and the student, using under-powered aircraft at first, would incrementally teach himself to fly until soloing. Pilots drifted into factions – Wright vs Curtiss due to these differences. These issues continued until 1915 when design differences, and the Wright aircraft, disappeared. There were also the ongoing legal battles between Curtiss and Wright. New York attorney Israel Ludlow, active in the Aero Club of America, wrote to navy captain Washington I. Chambers, “the patent litigation has stagnated the commercial development of the airplane in the United States”. Then in his biography of the Wrights, Fred Howard said, “In the years before World War I it seemed as if the infant aviation industry was being strangled by its umbilical cord – the Wright patent.” All of this - inaction, confusion, poor funding, and other distractions slowed the development of US aviation and specifically US military aviation. German, French, and British aviation suffered none of these and rapidly outclassed us as they prepared for war. Colonel Thomas DeWitt Milling, Chief of Air Service, First Army, in a report of lessons learned published in The US Air Service in World War I, Volume IV, wrote: 13 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2018

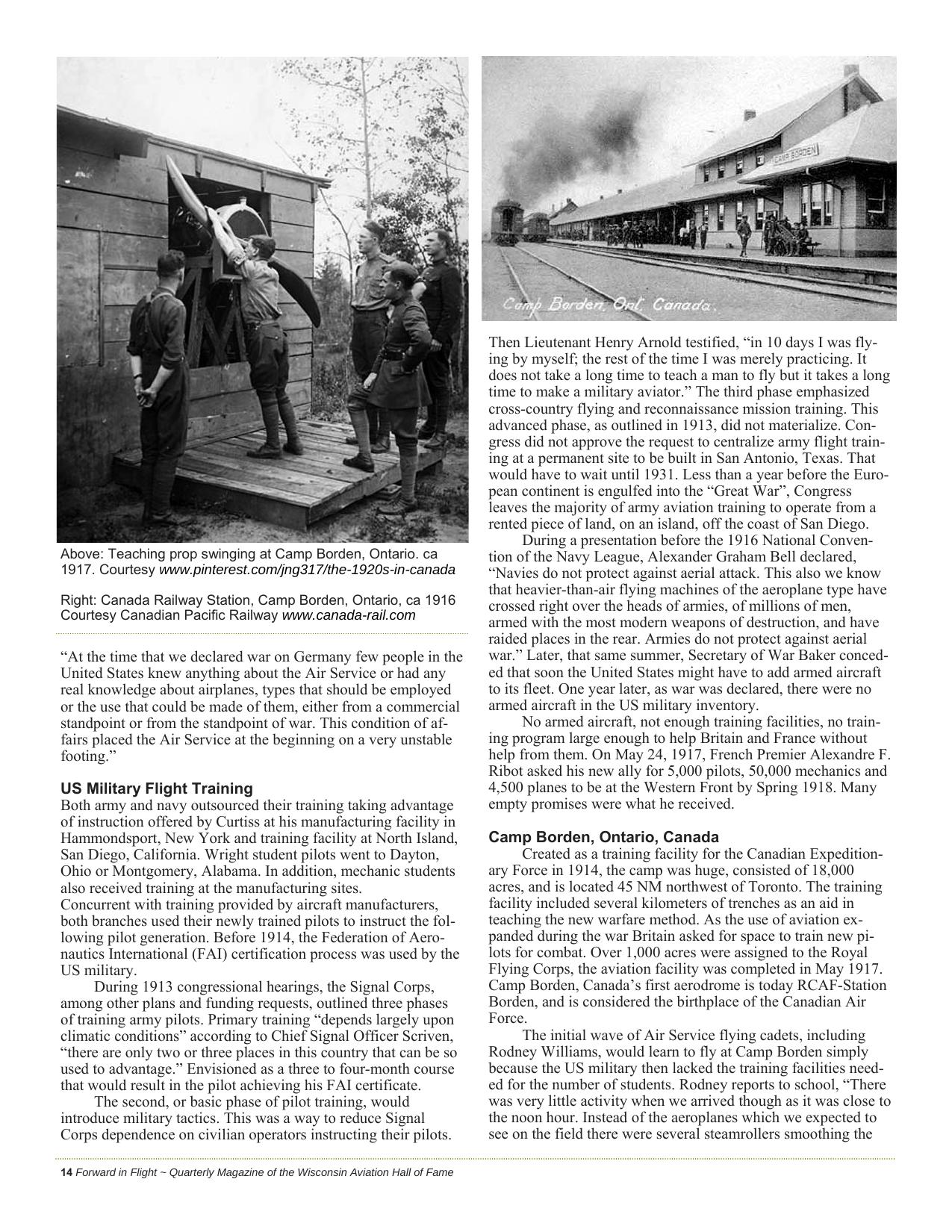

Above: Teaching prop swinging at Camp Borden, Ontario. ca 1917. Courtesy www.pinterest.com/jng317/the-1920s-in-canada Right: Canada Railway Station, Camp Borden, Ontario, ca 1916 Courtesy Canadian Pacific Railway www.canada-rail.com “At the time that we declared war on Germany few people in the United States knew anything about the Air Service or had any real knowledge about airplanes, types that should be employed or the use that could be made of them, either from a commercial standpoint or from the standpoint of war. This condition of affairs placed the Air Service at the beginning on a very unstable footing.” US Military Flight Training Both army and navy outsourced their training taking advantage of instruction offered by Curtiss at his manufacturing facility in Hammondsport, New York and training facility at North Island, San Diego, California. Wright student pilots went to Dayton, Ohio or Montgomery, Alabama. In addition, mechanic students also received training at the manufacturing sites. Concurrent with training provided by aircraft manufacturers, both branches used their newly trained pilots to instruct the following pilot generation. Before 1914, the Federation of Aeronautics International (FAI) certification process was used by the US military. During 1913 congressional hearings, the Signal Corps, among other plans and funding requests, outlined three phases of training army pilots. Primary training “depends largely upon climatic conditions” according to Chief Signal Officer Scriven, “there are only two or three places in this country that can be so used to advantage.” Envisioned as a three to four-month course that would result in the pilot achieving his FAI certificate. The second, or basic phase of pilot training, would introduce military tactics. This was a way to reduce Signal Corps dependence on civilian operators instructing their pilots. 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Then Lieutenant Henry Arnold testified, “in 10 days I was flying by myself; the rest of the time I was merely practicing. It does not take a long time to teach a man to fly but it takes a long time to make a military aviator.” The third phase emphasized cross-country flying and reconnaissance mission training. This advanced phase, as outlined in 1913, did not materialize. Congress did not approve the request to centralize army flight training at a permanent site to be built in San Antonio, Texas. That would have to wait until 1931. Less than a year before the European continent is engulfed into the “Great War”, Congress leaves the majority of army aviation training to operate from a rented piece of land, on an island, off the coast of San Diego. During a presentation before the 1916 National Convention of the Navy League, Alexander Graham Bell declared, “Navies do not protect against aerial attack. This also we know that heavier-than-air flying machines of the aeroplane type have crossed right over the heads of armies, of millions of men, armed with the most modern weapons of destruction, and have raided places in the rear. Armies do not protect against aerial war.” Later, that same summer, Secretary of War Baker conceded that soon the United States might have to add armed aircraft to its fleet. One year later, as war was declared, there were no armed aircraft in the US military inventory. No armed aircraft, not enough training facilities, no training program large enough to help Britain and France without help from them. On May 24, 1917, French Premier Alexandre F. Ribot asked his new ally for 5,000 pilots, 50,000 mechanics and 4,500 planes to be at the Western Front by Spring 1918. Many empty promises were what he received. Camp Borden, Ontario, Canada Created as a training facility for the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1914, the camp was huge, consisted of 18,000 acres, and is located 45 NM northwest of Toronto. The training facility included several kilometers of trenches as an aid in teaching the new warfare method. As the use of aviation expanded during the war Britain asked for space to train new pilots for combat. Over 1,000 acres were assigned to the Royal Flying Corps, the aviation facility was completed in May 1917. Camp Borden, Canada’s first aerodrome is today RCAF-Station Borden, and is considered the birthplace of the Canadian Air Force. The initial wave of Air Service flying cadets, including Rodney Williams, would learn to fly at Camp Borden simply because the US military then lacked the training facilities needed for the number of students. Rodney reports to school, “There was very little activity when we arrived though as it was close to the noon hour. Instead of the aeroplanes which we expected to see on the field there were several steamrollers smoothing the

surface of a newly sodded patch before some of the hangars. Driving up to one of the hangars we found a group of students at a machine gun class; they directed us to headquarters where we were told to report to the C.O. of the 88th Canadian Training Squadron at Ridley Park.” After visiting Camp Borden and the RAF’s School of Military Aeronautics located at the University of Toronto, the Signal Corps duplicated their ground school program at eight U.S. public and private universities. The schools were: Princeton University (New Jersey), University of Texas, Cornell University (New York), University of California, University of Illinois, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Georgia Institute of Technology and Ohio State University. The course was originally eight weeks in length, expanded to ten weeks, and ended as a 12week course of study. The army was playing catch up and time was running short. New flight training facilities rapidly became available about the same time Rodney had soloed and was building experience as a pilot. By October 31, 1917, fourteen new facilities had been built, flying training had begun at nine of them. Flight training was, and would remain, chaotic throughout the war. While a small amount of Air Service pilot training was conducted in the states during 1917, most of the training for Air Service pilots was done at Camp Borden. As stateside universities began aviation ground school courses that training was completed here. Late in 1917, as military training facilities were opened nearly all primary training of Air Service pilots would be completed stateside. The winter of 1917/1918 would see RFC and Canadian cadets moving to Texas training fields taking advantage of the better weather. Advanced training and “Type” training would take place in England, France, and, to a smaller, degree Italy. Inadequate support of aviation by the country where it was invented and failure to respond to world affairs are lessons hard learned. Unprepared was not just the case for the Air Service it permeated the entire Army. The Navy, while similar, led the Army in modern advances. As for Army aviation, in his recollections after the war, General Pershing lamented, The situation at that time. . . was such that every American ought to feel mortified to hear it mentioned. Out of the 65 officers and about 1,000 men in the Air Service Section of the Signal Corps, there were 35 officers who could fly. With the exception of five or six officers, none of them could have met the requirements of modem battle condition and none had any technical experience with aircraft guns, bombs or bombing devices. We could boast some 55 training planes in various conditions of usefulness, all entirely without war equipment and valueless for service at the front. WORLD WAR I 100th Year Commemoration I enjoy making repeated visits to museums because I am always discovering new things to learn and enjoy. Such was the case during a recent visit to the National Naval Aviation Museum at NAS Pensacola, Florida. Eight 2017 Graphic Art graduates of Pensacola State College created an outstanding exhibit celebrating the centennial of World War I. The exhibit opened November 3, 2017 with a reception held at the Naval Air Museum. The reception invitation read: 2017 Bachelor of Applied Science Graphic Design Exhibition - The WWI 100th Year Commemoration exhibition showcases the astonishing events, people, and innovation that came from the Great War. This collective body of work exemplifies the creative interpretation of World War I through color, fabrication, typography, photography, and design. Walk through the trenches and explore the deep history of how our world shook, crumbled, and evolved into what it is today. The exhibit will be on display through the remainder of this year. If you’re visiting the Gulf Coast this year please stop in to see their works. Promotional materials for the WWI Graphic Design Exhibition. Lessons hard learned and evidently easily forgotten. We would need to relearn those lessons less than 20 years later. SOURCES: N.H. Randers-Pehrson, History of Aviation (New York: National Aeronautics Council, 1944) Herbert Johnson, Wingless Eagle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) Rebecca Cameron, Training to Fly (Middleton: Progressive Management Publications, 1999). William E. Chajkowsky, Royal Flying Corps, Borden to Texas to Beamsville (Cheltenham, Boston Mills Press, 1979) Photos courtesy of John Dorcey 15 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2018

TAILSPINS Fighter Flyby By Tom “Tailspin” Thomas I was recently hangar flying with a fellow pilot about interesting flying experiences involving inflight refueling we did way back when. A story that came to my mind happened over a quarter century ago involving the EAA and the A-37B Dragon Fly. At the time I was flying the Dragon Fly with the Madison Air Guard Unit and had flown a local training sortie on July 30, 1981. As luck may have it, while the mission was being debriefed the possibility of a fly-by came up, opening the EAA Airshow on Saturday, August 1. The initial request submitted by Paul Poberezny came down through channels to the unit requesting four A-37Bs to hook up with a Milwaukee ANG KC-135A Saturday afternoon and open the air show. The Dragon Flys would hook up with the KC135A for practicing in-flight refueling and end our training mission by flying down Runway 18 at Wittman Field on the way home kicking off the opening of the “World’s Greatest Aviation Celebration” at Wittman Regional Airport (KOSH) at 1600. Hearing this, my hat was in the ring, immediately volunteering to fly one of our jets as did the three other pilots debriefing in the room. We were told it was a late afternoon go on Saturday, but that didn’t make any difference to us. This would be an air refueling training flight for me and having been checked out earlier in the month, was shooting for a left seat. Second thought, one would be happy with a right seat. Just to be able to participate in the EAA flyby would be a great honor. Luck sometimes being what it is, the four-ship with eight seat mission was cut to a two ship and somehow, I was magically assigned to fly the left seat in the second jet. Saturday, August 1 was to be a truly lucky day as my first student recommended for a private pilot’s flight check, passed with excellence. Her name was Dorothy and she was a grandmother who had taken lessons because she wanted to take her grandchildren for airplane rides. Her flight check was in a C-152 from Frickleton’s FBO on Dane County Regional Airport’s south ramp in Madison. Dorothy had demonstrated excellent pilot skills in our flights and the check pilot concurred. The instructor didn’t do it, the check pilot didn’t do it, Dorothy did it herself. August 1 was a somewhat hazy day in Madison with about five miles visibility. In an early morning guard flight, I’d been in the Dragon Fly’s right seat on a low-level training flight ending at Volk Field where we both flew two practice ILSs and returned midmorning at 15,000feet. We came back high to overfly the traffic inbound to Oshkosh and in the process were able to get a sneak preview of the afternoon’s weather out to the west. Except for the haze below 10,000feet and a few puffy clouds, it looked like the weather would be cooperating for the afternoon mission. After debriefing, the afternoon schedule had me going solo. Bill Walkington, a fellow guard pilot, had arrived mid-morning and grabbed the right seat. Bill was an active member of Madison’s EAA Corbin Chapter and had flown F86s in the Korean War as a 2nd Lieutenant. When chatting about the EAA, Bill shared an interesting story back in 1952 when Bob Hoover visited his base in Korea. Pilots had been complaining about the F-86 being under powered and lacked maneuverability. Bob was introduced to the pilots out on the ramp for a bit and some of the pilots were skeptical of his purported flying skills. Bob then walked out to one of the line jets. All eyes were on him as he did a walk around, climbed up and strapped in. After start, he taxied to the end of the runway and took off, keeping it low until the far end of the runway. Bob started a slow steady pull up into a smooth beautiful loop, then proceeded to perform the greatest F-86 air show that any of them had ever seen. All were impressed with the capability of the jet and no one ever complained again. Bill and I grabbed a cup of coffee and went to our assigned briefing room to cover the mission, including the tanker rendezvous procedures, frequencies, and contingencies. Once the paperwork was completed we headed to our jets and 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame were soon accelerating down Madison’s Runway 18 in the standard 3-foot formation take-off and departure. Once clear of the airport area, lead sent us to route formation to help clear for the climb out and tanker rendezvous. The tanker was one of Milwaukee’s KC-135s that I’d flown back in 1978 before transferring to Madison. Our rendezvous was in a track over Lake Michigan. Lead had briefed to make practice hookups before departing for Wittman Regional Airport to open the EAA Airshow at 1600 sharp. It took more than a bit of planning between the tanker’s navigator and Chicago Center to complete the timing, but we were well cared for. The tanker navigator was a friend who I’d flown with many times when flying both the KC-97L and KC-135A with Milwaukee. He was a math teacher in his 8-4 job in Milwaukee and known to be especially good with numbers, so we were in good hands. At FL190 we had the tanker in sight and headed up the refueling track for the join-up. The range was called off periodically by the Nav as we approached each other at 600mph. The tanker was coming down track, slightly off set to our left at FL200. The join-up was initiated by the Air Force Reserve Radar Unit located at Mitchell Field at the time and monitored by the Nav. As we approached each other, it looked like we might have an overrun developing, and always being ahead of the game, fighter lead had pre-briefed the possibility. He maneuvered our flight by slipping slightly inside to adjust, and ever so smoothly we slid in behind the big gas tank in the sky. We first joined on the tanker’s right wing, now cruising at 20,000-feet in clear, smooth air. Our flight conditions at altitude were severe clear. After stabilizing momentarily, our fighter, “Ram 42,” was cleared to the tanker’s 6 o’clock low, pre-contact position. The most challenging and fun part of the training requirements for the flight were about to begin. Sliding into position, the proper radio calls were made on the designated air refueling frequency with the

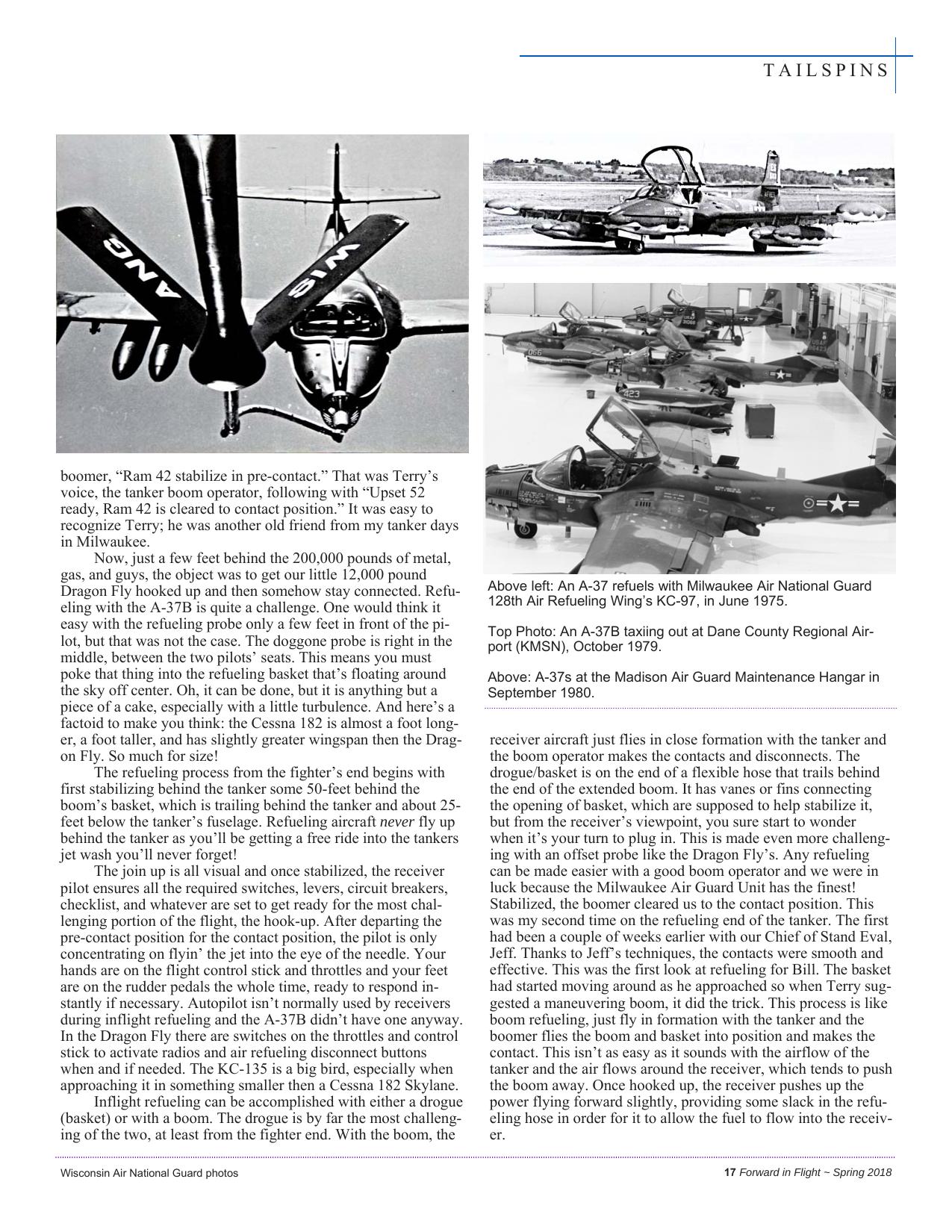

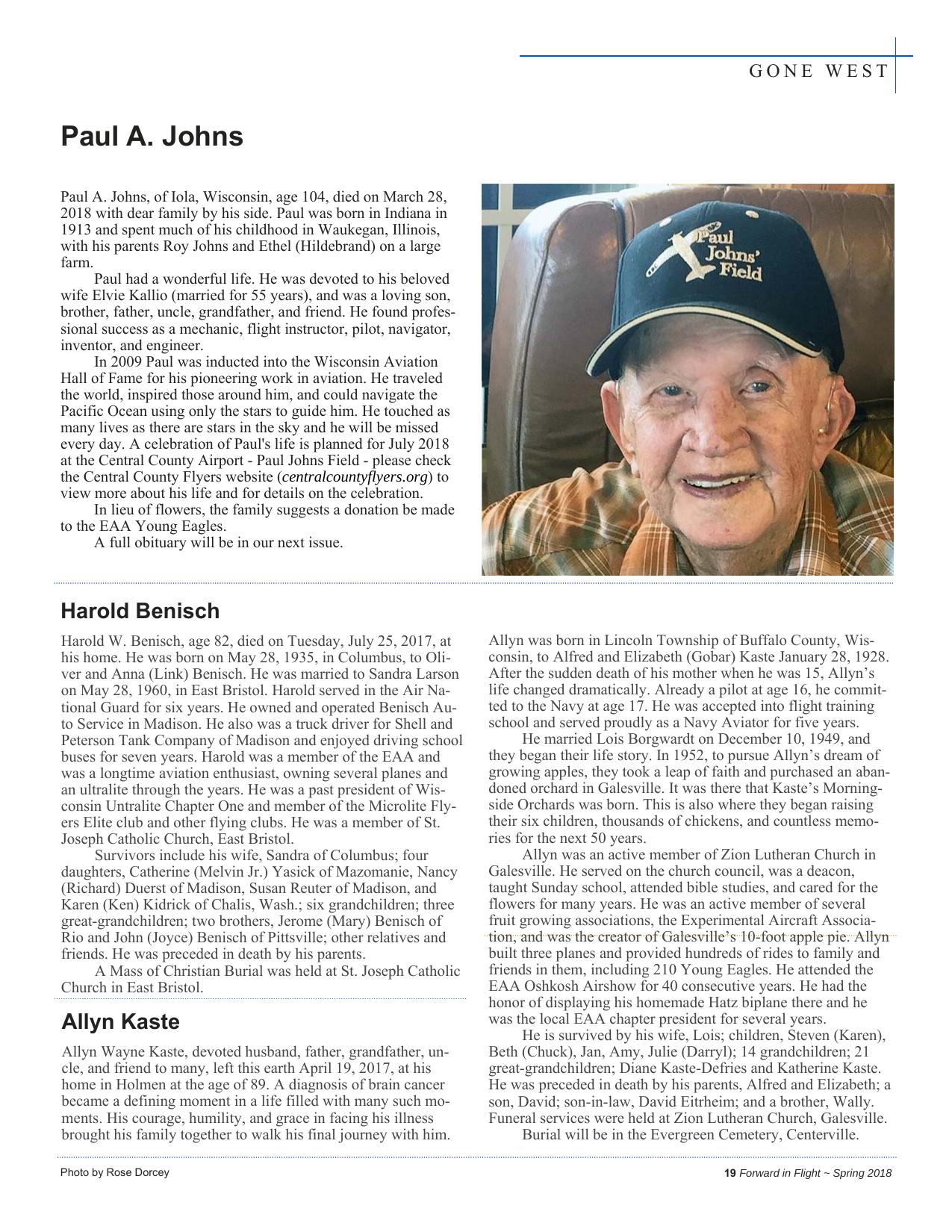

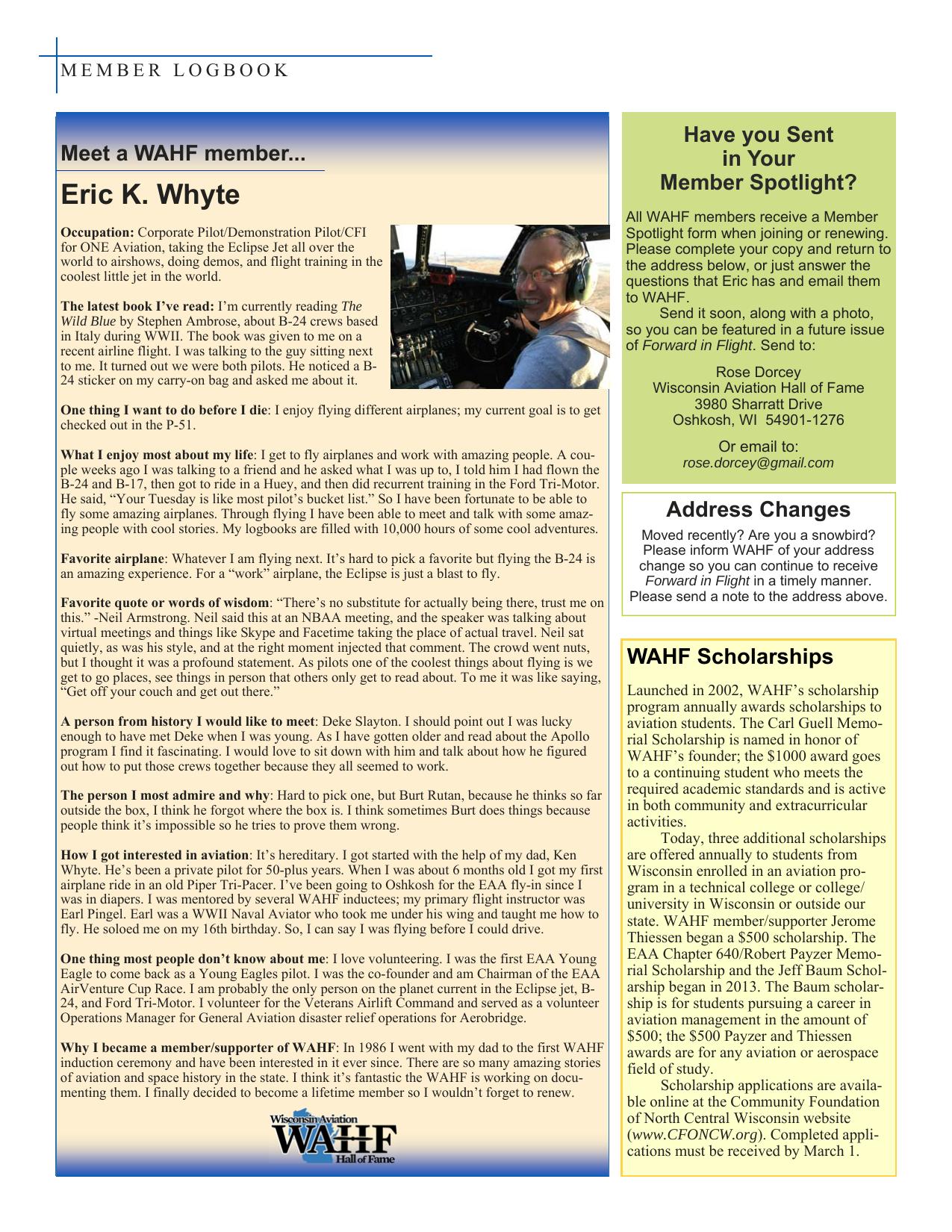

TAILSPINS boomer, “Ram 42 stabilize in pre-contact.” That was Terry’s voice, the tanker boom operator, following with “Upset 52 ready, Ram 42 is cleared to contact position.” It was easy to recognize Terry; he was another old friend from my tanker days in Milwaukee. Now, just a few feet behind the 200,000 pounds of metal, gas, and guys, the object was to get our little 12,000 pound Dragon Fly hooked up and then somehow stay connected. Refueling with the A-37B is quite a challenge. One would think it easy with the refueling probe only a few feet in front of the pilot, but that was not the case. The doggone probe is right in the middle, between the two pilots’ seats. This means you must poke that thing into the refueling basket that’s floating around the sky off center. Oh, it can be done, but it is anything but a piece of a cake, especially with a little turbulence. And here’s a factoid to make you think: the Cessna 182 is almost a foot longer, a foot taller, and has slightly greater wingspan then the Dragon Fly. So much for size! The refueling process from the fighter’s end begins with first stabilizing behind the tanker some 50-feet behind the boom’s basket, which is trailing behind the tanker and about 25feet below the tanker’s fuselage. Refueling aircraft never fly up behind the tanker as you’ll be getting a free ride into the tankers jet wash you’ll never forget! The join up is all visual and once stabilized, the receiver pilot ensures all the required switches, levers, circuit breakers, checklist, and whatever are set to get ready for the most challenging portion of the flight, the hook-up. After departing the pre-contact position for the contact position, the pilot is only concentrating on flyin’ the jet into the eye of the needle. Your hands are on the flight control stick and throttles and your feet are on the rudder pedals the whole time, ready to respond instantly if necessary. Autopilot isn’t normally used by receivers during inflight refueling and the A-37B didn’t have one anyway. In the Dragon Fly there are switches on the throttles and control stick to activate radios and air refueling disconnect buttons when and if needed. The KC-135 is a big bird, especially when approaching it in something smaller then a Cessna 182 Skylane. Inflight refueling can be accomplished with either a drogue (basket) or with a boom. The drogue is by far the most challenging of the two, at least from the fighter end. With the boom, the Wisconsin Air National Guard photos Above left: An A-37 refuels with Milwaukee Air National Guard 128th Air Refueling Wing’s KC-97, in June 1975. Top Photo: An A-37B taxiing out at Dane County Regional Airport (KMSN), October 1979. Above: A-37s at the Madison Air Guard Maintenance Hangar in September 1980. receiver aircraft just flies in close formation with the tanker and the boom operator makes the contacts and disconnects. The drogue/basket is on the end of a flexible hose that trails behind the end of the extended boom. It has vanes or fins connecting the opening of basket, which are supposed to help stabilize it, but from the receiver’s viewpoint, you sure start to wonder when it’s your turn to plug in. This is made even more challenging with an offset probe like the Dragon Fly’s. Any refueling can be made easier with a good boom operator and we were in luck because the Milwaukee Air Guard Unit has the finest! Stabilized, the boomer cleared us to the contact position. This was my second time on the refueling end of the tanker. The first had been a couple of weeks earlier with our Chief of Stand Eval, Jeff. Thanks to Jeff’s techniques, the contacts were smooth and effective. This was the first look at refueling for Bill. The basket had started moving around as he approached so when Terry suggested a maneuvering boom, it did the trick. This process is like boom refueling, just fly in formation with the tanker and the boomer flies the boom and basket into position and makes the contact. This isn’t as easy as it sounds with the airflow of the tanker and the air flows around the receiver, which tends to push the boom away. Once hooked up, the receiver pushes up the power flying forward slightly, providing some slack in the refueling hose in order for it to allow the fuel to flow into the receiver. 17 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2018