Forward in Flight - Spring 2021

Volume 19, Issue 1 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Spring 2021

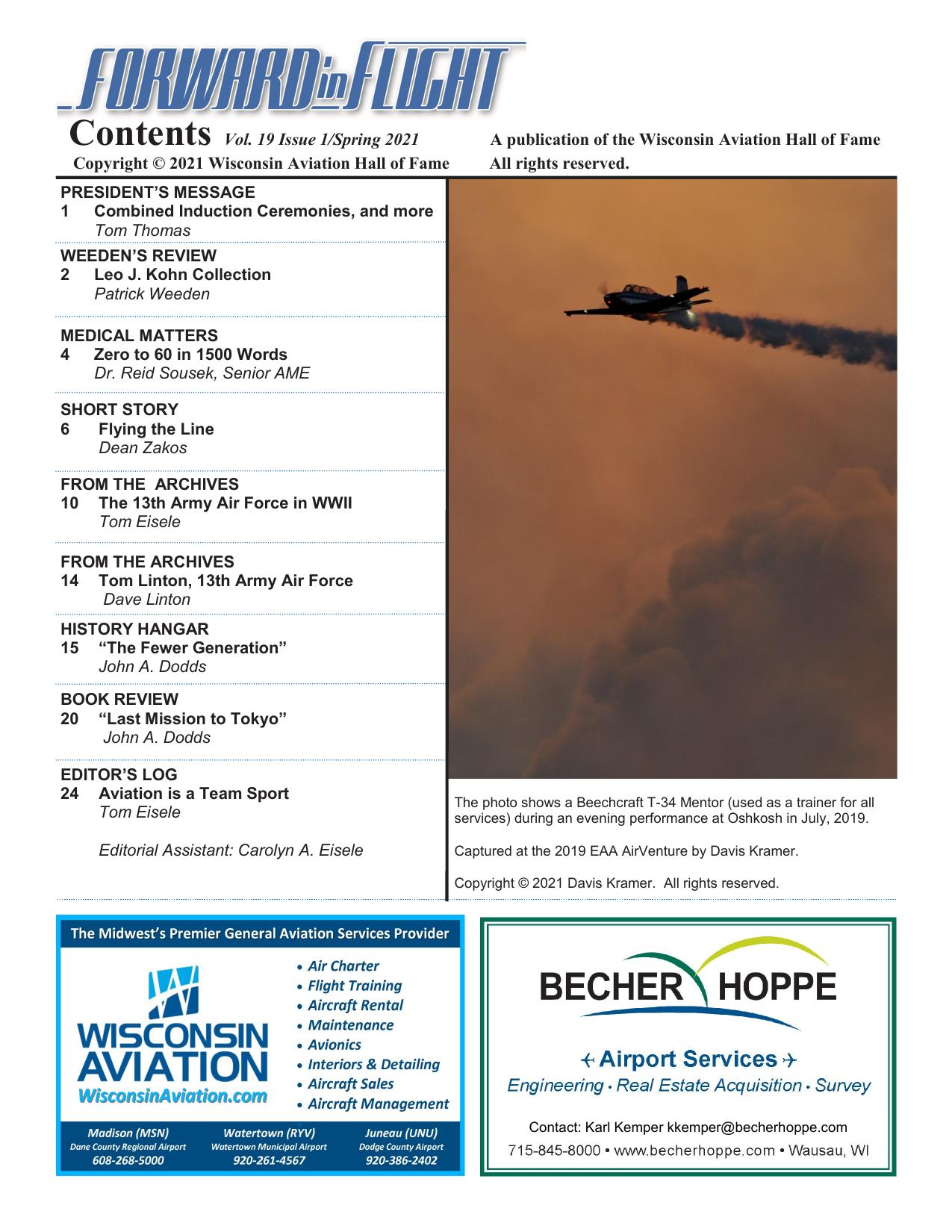

Contents Vol. 19 Issue 1/Spring 2021 Copyright © 2021 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All rights reserved. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 1 Combined Induction Ceremonies, and more Tom Thomas WEEDEN’S REVIEW 2 Leo J. Kohn Collection Patrick Weeden MEDICAL MATTERS 4 Zero to 60 in 1500 Words Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME SHORT STORY 6 Flying the Line Dean Zakos FROM THE ARCHIVES 10 The 13th Army Air Force in WWII Tom Eisele FROM THE ARCHIVES 14 Tom Linton, 13th Army Air Force Dave Linton HISTORY HANGAR 15 “The Fewer Generation” John A. Dodds BOOK REVIEW 20 “Last Mission to Tokyo” John A. Dodds EDITOR’S LOG 24 Aviation is a Team Sport Tom Eisele Editorial Assistant: Carolyn A. Eisele The photo shows a Beechcraft T-34 Mentor (used as a trainer for all services) during an evening performance at Oshkosh in July, 2019. Captured at the 2019 EAA AirVenture by Davis Kramer. Copyright © 2021 Davis Kramer. All rights reserved. Contact: Karl Kemper kkemper@becherhoppe.com

President’s Message By Tom Thomas January 2021 sure went out like a lion; let’s all hope it took some COVID with it. The vaccines are becoming more available, which is a good thing. One can look at the increasing distribution of COVID vaccines as the air starting to flow over our wings. The 2020/2021 COVID anomaly basically hit every aspect of our lives. We would all like that healing air “flowing over our wings” to go faster, of course; as distribution of vaccines accelerates, the associated lift for our aviation world can increase our healing process. Prior to our January WAHF Board meeting, we had contacted the EAA staff with whom we had been working, in order to schedule the delayed 2020 Induction Ceremonies. The EAA staff had tentatively reserved the dates of April 10th and May 29th for the 2020 Induction Ceremony. We had selected the second date just in case COVID was still a serious issue for the earlier date. The EAA staff had been working on their internal process for the Founders Room and had provided us with them for our consideration. We believed these arrangements were viable options, as a result of increased vaccine distribution and with dropping COVID numbers. The current COVID projections aren’t as good as we had hoped. Still, EAA was willing to work with us under fairly strict guidelines so as to hold the 2020 Induction Ceremony this spring. Our winter WAHF Board Meeting was a call-in virtual meeting on January 21st. After thoroughly discussing all of the options, and in view of the initial delays with distributing the vaccine, and even some new virus strains popping up, we notified the EAA that we would drop the April and May dates for the Ceremony. We now plan on having both Induction Ceremonies – for 2020 and for 2021 – on Saturday, October 23rd. The WAHF Board also has worked on setting goals and incorporating new ideas to simplify and streamline processes for our Members and the Board. One idea that has worked well is communicating with WAHF members via email. We have less than half of our members’ email addresses. We now ask that you include your email address with your renewal application (if you haven’t yet mailed your renewal). Forward in Flight the only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s aviation events. Tom Eisele, editor W8863 U.S. Highway 12 Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-9762 513-484-0394 t.d.eisele@att.net The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. For all of you who have already mailed in your renewals, Thank You! If you didn’t include your email address with your renewal, please forward your address to my email address: <tomas317@live.com> Some good news is surfacing regarding AirVenture 2021. It is now being planned for July 26 th through August 1st. This event will be different from what we have experienced over the years. There will be new guidelines developed with more emphasis on outdoor activities. Indoor activities may have to be limited to meet required spacing guidelines. We all will be watching for updates and guidance from the EAA. Again, thanks to all of you who have already renewed your WAHF Membership! Thirty-one years ago, July 23, 1990, I flew with Squadron Leader David Moss in his British Tornado F3 on a mission over the North Sea. The F3 is an Air Superiority Interceptor. It has variable/swing wings, Mach 2+ speed. Service Ceiling FL 50,000’. I operated its radar and got 5 Lock Ons. It was smooth– fast - and it stopped in 500’ with reverse thrust cams. “Yes, 85% of life is showing up!” On the cover: A 4-ship formation of the USAF Thunderbirds team. Photo taken at the Reno, Nevada air show, in March, 2017. Photo courtesy of the Px.Here.com website. Released to the Collective Commons.

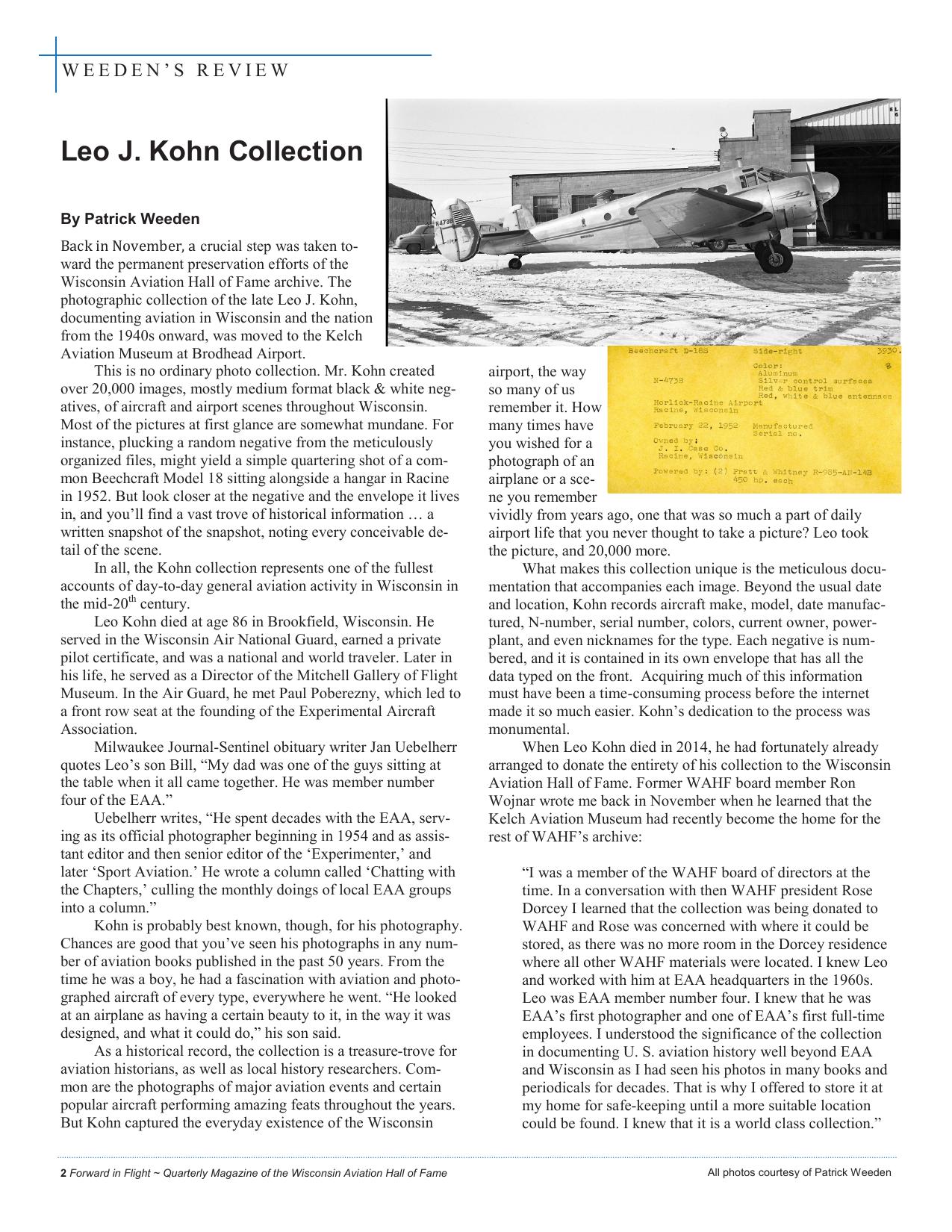

WEEDEN’S REVIEW Leo J. Kohn Collection By Patrick Weeden Back in November, a crucial step was taken toward the permanent preservation efforts of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame archive. The photographic collection of the late Leo J. Kohn, documenting aviation in Wisconsin and the nation from the 1940s onward, was moved to the Kelch Aviation Museum at Brodhead Airport. This is no ordinary photo collection. Mr. Kohn created over 20,000 images, mostly medium format black & white negatives, of aircraft and airport scenes throughout Wisconsin. Most of the pictures at first glance are somewhat mundane. For instance, plucking a random negative from the meticulously organized files, might yield a simple quartering shot of a common Beechcraft Model 18 sitting alongside a hangar in Racine in 1952. But look closer at the negative and the envelope it lives in, and you’ll find a vast trove of historical information … a written snapshot of the snapshot, noting every conceivable detail of the scene. In all, the Kohn collection represents one of the fullest accounts of day-to-day general aviation activity in Wisconsin in the mid-20th century. Leo Kohn died at age 86 in Brookfield, Wisconsin. He served in the Wisconsin Air National Guard, earned a private pilot certificate, and was a national and world traveler. Later in his life, he served as a Director of the Mitchell Gallery of Flight Museum. In the Air Guard, he met Paul Poberezny, which led to a front row seat at the founding of the Experimental Aircraft Association. Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel obituary writer Jan Uebelherr quotes Leo’s son Bill, “My dad was one of the guys sitting at the table when it all came together. He was member number four of the EAA.” Uebelherr writes, “He spent decades with the EAA, serving as its official photographer beginning in 1954 and as assistant editor and then senior editor of the ‘Experimenter,’ and later ‘Sport Aviation.’ He wrote a column called ‘Chatting with the Chapters,’ culling the monthly doings of local EAA groups into a column.” Kohn is probably best known, though, for his photography. Chances are good that you’ve seen his photographs in any number of aviation books published in the past 50 years. From the time he was a boy, he had a fascination with aviation and photographed aircraft of every type, everywhere he went. “He looked at an airplane as having a certain beauty to it, in the way it was designed, and what it could do,” his son said. As a historical record, the collection is a treasure-trove for aviation historians, as well as local history researchers. Common are the photographs of major aviation events and certain popular aircraft performing amazing feats throughout the years. But Kohn captured the everyday existence of the Wisconsin 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame airport, the way so many of us remember it. How many times have you wished for a photograph of an airplane or a scene you remember vividly from years ago, one that was so much a part of daily airport life that you never thought to take a picture? Leo took the picture, and 20,000 more. What makes this collection unique is the meticulous documentation that accompanies each image. Beyond the usual date and location, Kohn records aircraft make, model, date manufactured, N-number, serial number, colors, current owner, powerplant, and even nicknames for the type. Each negative is numbered, and it is contained in its own envelope that has all the data typed on the front. Acquiring much of this information must have been a time-consuming process before the internet made it so much easier. Kohn’s dedication to the process was monumental. When Leo Kohn died in 2014, he had fortunately already arranged to donate the entirety of his collection to the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. Former WAHF board member Ron Wojnar wrote me back in November when he learned that the Kelch Aviation Museum had recently become the home for the rest of WAHF’s archive: “I was a member of the WAHF board of directors at the time. In a conversation with then WAHF president Rose Dorcey I learned that the collection was being donated to WAHF and Rose was concerned with where it could be stored, as there was no more room in the Dorcey residence where all other WAHF materials were located. I knew Leo and worked with him at EAA headquarters in the 1960s. Leo was EAA member number four. I knew that he was EAA’s first photographer and one of EAA’s first full-time employees. I understood the significance of the collection in documenting U. S. aviation history well beyond EAA and Wisconsin as I had seen his photos in many books and periodicals for decades. That is why I offered to store it at my home for safe-keeping until a more suitable location could be found. I knew that it is a world class collection.” All photos courtesy of Patrick Weeden

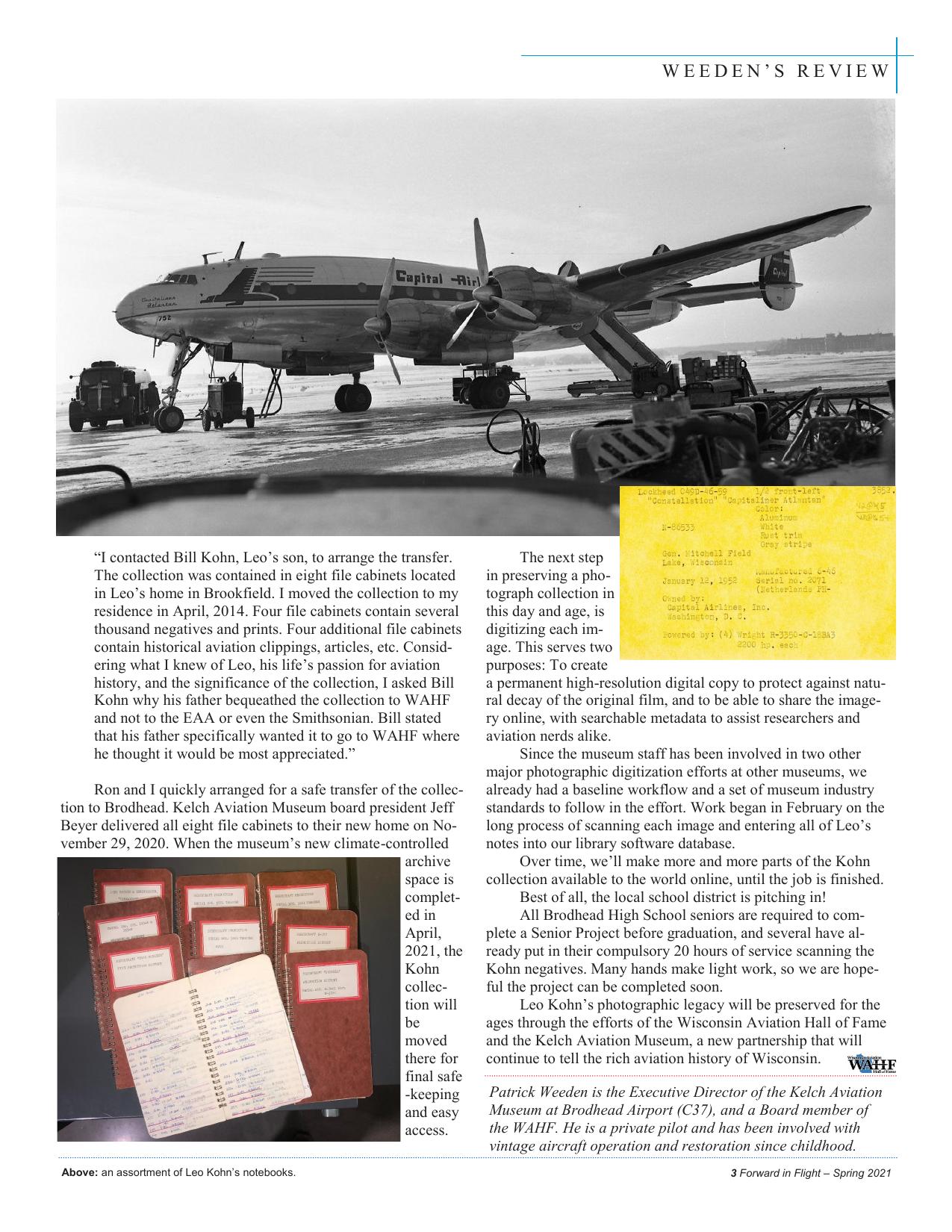

WEEDEN’S REVIEW “I contacted Bill Kohn, Leo’s son, to arrange the transfer. The collection was contained in eight file cabinets located in Leo’s home in Brookfield. I moved the collection to my residence in April, 2014. Four file cabinets contain several thousand negatives and prints. Four additional file cabinets contain historical aviation clippings, articles, etc. Considering what I knew of Leo, his life’s passion for aviation history, and the significance of the collection, I asked Bill Kohn why his father bequeathed the collection to WAHF and not to the EAA or even the Smithsonian. Bill stated that his father specifically wanted it to go to WAHF where he thought it would be most appreciated.” Ron and I quickly arranged for a safe transfer of the collection to Brodhead. Kelch Aviation Museum board president Jeff Beyer delivered all eight file cabinets to their new home on November 29, 2020. When the museum’s new climate-controlled archive space is completed in April, 2021, the Kohn collection will be moved there for final safe -keeping and easy access. Above: an assortment of Leo Kohn’s notebooks. The next step in preserving a photograph collection in this day and age, is digitizing each image. This serves two purposes: To create a permanent high-resolution digital copy to protect against natural decay of the original film, and to be able to share the imagery online, with searchable metadata to assist researchers and aviation nerds alike. Since the museum staff has been involved in two other major photographic digitization efforts at other museums, we already had a baseline workflow and a set of museum industry standards to follow in the effort. Work began in February on the long process of scanning each image and entering all of Leo’s notes into our library software database. Over time, we’ll make more and more parts of the Kohn collection available to the world online, until the job is finished. Best of all, the local school district is pitching in! All Brodhead High School seniors are required to complete a Senior Project before graduation, and several have already put in their compulsory 20 hours of service scanning the Kohn negatives. Many hands make light work, so we are hopeful the project can be completed soon. Leo Kohn’s photographic legacy will be preserved for the ages through the efforts of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame and the Kelch Aviation Museum, a new partnership that will continue to tell the rich aviation history of Wisconsin. Patrick Weeden is the Executive Director of the Kelch Aviation Museum at Brodhead Airport (C37), and a Board member of the WAHF. He is a private pilot and has been involved with vintage aircraft operation and restoration since childhood. 3 Forward in Flight – Spring 2021

MEDICAL MATTERS Zero to 60 in 1500 Words Filling out FAA Form 8500-8 (Part I) By Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME Technically speaking, it could be “0 to 64” … but that just doesn’t sound right. In the next two pages, we will cover the required airman’s responses prior to a “flight physical.” These items make up the first portion of an FAA Form 8500-8. We will go through each of the numbers/blanks and discuss why the question is asked. Then we will focus on the questions that may be most confusing, or are most likely to trip up your application for a medical. From the airman’s side of things, these questions are entered when the MedXpress form is completed online (https:// medxpress.faa.gov/medxpress/). Prior to 2012, the FAA still accepted paper 8500-8 forms. Then, in October of 2012, the FAA switched completely to the online MedXpress. Upon completion and submission of this form, a confirmation number will be provided to the airman. Do not lose this. Without this number, the Aviation Medical Examiner (AME) will not be able to submit the results of your exam. So, you are wasting time if you go to your AME’s office without having completed online a MedXpress form. A completed MedXpress form remains valid for 60 days after submission. After 60 days, it is automatically deleted. If the confirmation number is not entered by an AME, there simply will be no records from the FAA standpoint. The First Two Questions The first question or blank to be completed is for the application type: Medical, or Medical and Student pilot. Historically, this was an important question. However, on 4/01/2016, this became obsolete. Due to a new regulation (81 FR 1292), AMEs no longer issue a combined Medical and Student Pilot certification. Now AMEs only issue the Medical Certificate. The Student Pilot certificate is now obtained through the Flight Standards District Office (FSDO). This change was enacted so the Transportation Safety Administration could vet all student pilots. The next blank is selecting which class of medical certificate the airman is seeking. Many readers may already know that in General Aviation, many pilots seek a 3rd class certificate. Professional pilots will need a 2nd or 1st class certificate to fly for hire. However, there are also some non-pilots who need an FAA medical certificate. One example of a non-pilot needing a certificate would be a contracted Air Traffic Controller (ATC). An ATC who works in an FAA facility (think “major airport tower/center”) will 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame generally be required to see specific FAA-designated examiners for the ATC exam. Those who work at smaller airports, which use contracted ATC, will be able to see any AME. The other “non-pilot” that I see on occasion would be a tandem skydive instructor. These individuals will be required to have medical certification to carry a passenger, but they may not need certification to jump alone. The Next 14 Questions Numbers 3 through 12 are items such as address, hair and eye color, current ratings, occupation, and employer. Other items documented here include airman certificates held (#10) and flight hours (#14 and #15). These may come into play where a Statement of Demonstrated Ability (SODA) is considered. For address changes after the exam, the airman should notify the FAA within 30 days of the examination, so as to remain in compliance with the Code of Federal Regulations. This notification may be performed online at the Airman Services website: (https://amsrvs.registry.faa.gov/amsrvs/Logon.asp). Per the FAA website, the occupation and employer information are only for statistical purposes. Item 16 is Date of Last FAA Medical Application. If you are uncertain of the exact date, make your best estimate, even if you only remember the year it was done. Question 17 – Multiple Topics Now we get to the topics with multiple sub-items. Question 17(a) concerns the use of any medications, prescription or non-prescription. While there are some medications that are obviously not compatible with safe flight, there are many that may seem harmless, but are still not safe for flying. Many aviation groups have lists posted on their website; these lists try to cover which meds are safe or not safe for flight. These lists, however, are not all-encompassing. Your best bet would be to discuss any new meds with your AME, rather than simply rely on a website. Not only are medication side effects evaluated by an AME, but also the underlying condition being addressed by the medication. Question 17(b) is possibly the question most often incorrectly answered.

MEDICAL MATTERS This question is: “Do you ever use near vision contact lens (es) while flying?” Many people will miss the word “near” in this question. This is not asking about regular contacts, but rather a near vision contact which would be used to create monovision. With this type of vision correction, one eye is corrected for distance and one for near vision. While initially this may be quite disorienting, over time most individuals adapt to this difference and can perform most daily activities. Still, this vision correction can affect depth perception. This impact to depth perception is not compatible with safe flight and therefore not allowed by the FAA. Other contact lens types (such as bifocal or multifocal contact lenses) are allowed as long as the vision standards for the appropriate medical class are met (and the lenses have been used for at least a month). Question 18 – The Big One Item 18 is the big one. It is actually made up of 25 subquestions: (a) through (y). These questions inquire as to whether you have ever had a specific condition in your life, or, whether you currently have specific conditions. This part goes through every organ system, including your mental health and substance abuse history. It asks about medical military discharges or disabilities, in addition to rejection for life insurance. One of the last questions under #18 asks about “any other illness, disability, or surgery,” so everything and anything medically pertinent is captured. Every “yes” under item 18 requires a comment or response. While many pilots simply write “PRNC” (that is, previously reported no change), this is not the ideal response. Since most of these items are very broadly questioned, it is helpful to the AME and FAA to have some description of the condition, even if it is brief. For example, if your positive response under “other illness, disability, or surgery” refers to a knee surgery 20 years ago and a colonoscopy 5 years ago, you need to document both of them in that manner. That way, everyone involved knows that we are referring to the same conditions or events. The other few items that need special attention are questions 18(n), 18(o), 18(v), and 18(w). These are questioning the presence of any alcohol or substance use. Question 18(v), in particular, questions any Arrest, Conviction, and/or Administrative Action with regards to driving. As we will discuss in a few paragraphs, the FAA does search the National Driver Register with each application. If you knowingly answer incorrectly, or try to hide a DUI, I wish you the best. It is going to be a bumpy landing for you. A key item here is that the FAA is looking for not only convictions, but also arrests or administrative actions. So, if you are pulled over and arrested for a DUI, but then your lawyer gets you off on a technicality, or somehow the charges get reduced, this incident still must be reported. I do know at least one pilot who falsely checked “No” in this section.Ultimately, the pilot had not just his medical denied but also all of his Airman Certificates revoked (Private all the way up through ATP). Questions 19 and 20 Moving on to #19, we must now document any visits with health professionals over the last 3 years. This is pretty self-explanatory and can get quite tedious in some cases. To clarify, the FAA states that any visit with a “physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, psychologist, clinical social worker, or substance abuse specialist for treatment, examination, or medical/mental evaluation. The applicant should list visits for counseling only if related to a personal substance abuse or psychiatric condition.” Multiple visits for the same reason can often be combined on one line. Additionally, “routine dental, eye, and FAA periodic medical examinations and consultations with an employer-sponsored employee assistance program (EAP) may be excluded unless the consultations were for the applicant's substance abuse or unless the consultations resulted in referral for psychiatric evaluation or treatment.” So, perhaps the tedium of reporting these visits is somewhat reduced by this exclusion. We now come back to question # 20. This is the authorization for the FAA to search the National Driver Register. This is where the drug or alcohol motor vehicle actions may come to light. This authorization is consented to by the airman when the MedXpress form is signed and the confirmation # is provided to the AME by the airman. What’s next? With the MedXpress form completed and confirmation number in hand, you are ready for your flight physical. If you do have any ongoing medical conditions, it will likely be beneficial to start getting copies of medical records. Next time, we will cover what to expect when you show up for your physical ... and what is the deal with that Titmus Vision Screener anyway? [Dr. Reid Sousek is an FAA-designated Senior Aviation Medical Examiner, who offers Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 Pilot Medical Exams; and an HIMS AME, for drug/alcohol exams. Dr. Sousek has offices near Oshkosh and Menasha.] 5 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021

SHORT STORY Flying the Line For Eddy, who loves to fly By Dean Zakos I was startled awake. The buzzing alarm clock did its job exceedingly well. It was a raw, windy day in March of 1971, and I needed to get up. The North Central Convair 580 waiting on the ramp would not fly itself. I had been with our “local service carrier” airline since 1964 and sported four silver stripes on the dark blue sleeves of my uniform since the beginning of the year. My days on the line were starting to seem routine, but I also knew each one would be different and distinguishable; schedules, maintenance issues, destinations, weather, and crew personalities, all contributed to that. I made my way to North Central’s Flight Ops at O’Hare, located beneath Gate H1, and signed in at the crew scheduling counter. Today’s flight had us departing from Chicago at 0630, with stops along our route at Milwaukee (MKE), Green Bay (GRB), Menominee (MNM), Escanaba (ESC), and Marquette (MQT). In the afternoon, we would return to ORD by the same route. The weather for the day would be “predictable” for Wisconsin at this time of year; that is, a bit unpredictable. Forecast was scattered clouds over the southern half of Wisconsin; overcast skies, dropping temperatures, and gusty winds, landing in Green Bay; and some rain/snow showers and reduced visibility in route to Menominee and Escanaba. Clearing skies in the afternoon. In 1971, navigation was less sophisticated than it is today. No GPS, just Victor airways and direct routes. A few larger airports we flew into, such as ORD, MSP, DTW, MKE, and GRB, had ILS approaches, but many smaller fields did not. ADFs were still a valuable instrument in the cockpit, as NCA had installed several FAA-approved custom NDB approaches into smaller cities. The approach into Duluth (DLH) was a Precision Radar Approach with military controllers. North Central had upgraded its fleet in 1967 to include the Convair 580, a turbine-powered conversion of the Convair 440 piston-powered aircraft. The 580 was a big improvement over the 440, with two T56/501 4,000 shaft horsepower Allison engines. An inside joke among NCA personnel was that the airplane was known as the “Converter 580” because of its ability to turn Jet A into pure noise. It was a good airplane that did everything it was asked to do, with long wings, excellent aileron authority, and widely-spaced main landing gear. When the FAA certified the turboprop conversion, they required a bungee interconnect between the rudder and the ailerons. We had to contend with the artificial loads imposed on the controls in addition to normal air loads. This resulted in requiring some muscle when landing in strong cross-winds. The wings were a little stiff, often generating pretty solid bumps in turbulence. 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame The 580 could carry up to 48 passengers and a crew of three: Captain, First Officer, and a Stewardess. And yes, I know they are called Flight Attendants today. In 1971, the Flight Attendants wore white hats, dark blue jacket and skirt combos, and white go-go boots. Standing just inside the Convair’s open airstair door, boarding passengers on a March day in the Upper Peninsula, it had to be chilly on bare legs. It was not unusual at NCA to fly with the same FO and FA for the entire month. As a boy, I never really thought seriously about becoming a pilot. My dad always wanted me to be a doctor. However, my experience in organic chemistry made it clear to me that my best talents were to be found elsewhere. In college, I participated in the Air Force ROTC program, graduating with a BA degree. Upon graduation, I entered military service. However, not as a pilot, but as a supply officer. I quickly realized who was having all the fun. I applied for pilot training and was accepted. Basic at Williams Air Force Base in Phoenix, flying T37s and T-38s. Next assignment was to Training Command at Shepard Air Force Base in Wichita Falls instructing in T-37s, then the USAF Reserves. Walking out onto the ramp at ORD in the early dawn, I looked up at “Herman,” the blue duck painted on the tail of our aircraft. The sun was just beginning its rise over the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. The Convair sat waiting and ready, ground-start cart plugged in, the smell of jet fuel drifting across the ramp. Mechanics and line crew scurried to complete tasks, with passengers about to board. I often paid little attention to the North Central logo over those years. I admit now I took it for granted. How I wish I could see that logo again on the tail of a passenger plane. The First Officer will be flying this leg. Once I settled into the left seat, the FO and I ran our “Receiving Aircraft” and “Before Start” checklists. Passenger count showed thirty-seven souls joining us this morning. Looking back through the open cockpit door, I could see the rows of twin seats, with ample headroom and leg room compared to today, and the “hat rack” style shelves running the length of the cabin on either side. It is hard to believe now that most men boarding the plane wore suits Copyright © 2021 Dean Zakos. All rights reserved.

SHORT STORY and ties, most women wore dresses, and many children were dressed as if it were Easter Sunday. Our clearance out of ORD was “North Central three-four-three cleared to the Milwaukee airport via left turn after takeoff to two-seven-zero, radar vectors to the Northbrook VOR, then as filed, climb to and maintain five thousand, contact Departure on one-two-six-point-five. Squawk four-three-four-six.” At that altitude, it was easy to watch the cities, rural airports, farm fields, and sectional lines that passed underneath us through scattered clouds. Lake Michigan would be on our right along the route. I was always impressed with the stunning arrays of blue and green hues the sun and clouds produced daily on the water. After engine start, with my left hand on the nosewheel steering wheel beside my seat, we taxied out to our assigned runway, 32L. We challenged and responded to eighteen items on the “Before Takeoff” checklist. The last item is the annunciator panel located on the center console. We confirmed four amber, six green, and no red lights. We are ready to go. Upon takeoff clearance from the Tower, we taxi onto the runway. The FO advances the power levers. The Allison T56s respond instantly. Engine vibrations are smooth and steady as we started our rumbling takeoff roll. At 110 knots, I call “Vee one.” At 112 knots, the FO pitches the nose up eight degrees. I confirm positive rate, then the FO calls “Gear up,” simultaneously giving a thumb-up with his left hand, as we climbed out over the end of the runway. Passing 130 knots, the FO calls for “METO” power. At 400 feet above ground level, the FO requests “Flaps zero,” then calls “Climb power.” He then asks for the “Climb” checklist. Light but constant winds this morning. While ascending in our left turn, I contact Departure when advised and we are given our next heading. With short flying legs, things happen quickly. Estimated time in route to MKE was only thirty minutes. The Stewardess always had her hands full on such short hops. Barely enough time to serve a tray of pre-poured beverages and get things stowed away before landing. We are handed off to Milwaukee Approach. I report Mitchell Field in sight. Approach clears us for a visual approach to Runway 1L.The FO calls for the “In Range” checklist. We agree on approach flap settings and approach speeds. At 1,000 feet above the ground, the FO asks for “Flaps oneseven,” and then “Gear down.” Next, “Flaps two-eight,” and we slow to “VRef plus five,” or about 130 knots. I have seen the view of a runway-on-final out of a cockpit window countless times, but I never tire of it. The stark blue and white of the sky this morning, the rolling stream of farm fields, roads, and buildings flowing by beneath us, the runway threshold growing larger in front of us, the controlled descent as we managed small adjustImages throughout courtesy of Dean Zakos ments to remain on speed and on glidepath, make each landing at once both familiar and unique. The FO calls for the “Before Landing” checklist. I advise Milwaukee Tower, “North Central three-four-three is five miles to the south, inbound on visual approach straight in Runway One Left.” “Cleared to land, winds zero-two-zero at one-two,” the Tower answered. The Convair brushes onto the runway. First leg complete. We taxied to Concourse E, known to us as “the Banjo,” and shut down. The FO opened the forward entrance door and airstair. Fourteen passengers deplaned. Eight new passengers boarded at MKE. Inside the terminal, as we did at each stop, I checked with Dispatch and reviewed the “Papers,” including weight and balance and a long sheet of teletype paper containing weather and NOTAMs. The fast-moving front, coming from the northwest, was arriving sooner than anticipated. Green Bay’s weather was deteriorating. At our estimated arrival time, forecast was five hundred and one in light mist and snow showers. Winds were picking up. My leg to fly. Time on the ground at MKE was thirty minutes. Then, we were in the air again. Estimated time in route to GRB was fifty-five minutes, assuming no lengthy vectors by ATC. Climbing out of MKE, Lake Winnebago quickly came into view in the distance off the port wing. The southern half of the lake near Fond du Lac was shimmering in sunshine and scattered clouds, but the northern half was difficult to discern, shrouded in overcast. East of Appleton at 5,000 feet, we were in IMC. There was some light to moderate turbulence. Hopefully, not 7 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021

SHORT STORY too many new or white-knuckle passengers on this leg. I asked the FO for current conditions at Green Bay. Ceiling and visibility as advertised, and winds from the northeast, one-eight gusting to two-eight. Chicago Center tells us to expect the ILS 36 into GRB. We remove the approach plates from our Jeppesen binders and clip them on our control yokes. I begin the briefing by identifying the exact name and date on the plate. I then call out the localizer frequency, approach course, runway length, touchdown zone elevation, approach and runway lights, and crossing altitude at the Final Approach Fix. Next, I review the Decision Height, minimum visibility, and the missed approach procedure. I always thought a good briefing was essential to functioning as a team. We are handed off to Green Bay Approach. After vectors and a descent to 2,700 feet, the call comes from Approach, “North Central three-four three, turn left to zerothree-zero to intercept the localizer. Maintain two thousand seven hundred until established. Cleared ILS Three-Six approach. Contact Tower on one-one-eight-point-seven.” As the First Officer read back our clearance, we commenced our turn. Contacted Tower. Winds were zero-three-five, one-five gusting to two-six. The ADF needle is pointing to the Locator Outer Marker. The localizer indicators on the HSIs in our panel soon started to center. Cross the Final Approach Fix and center the glide slope pointers at twenty-two hundred feet. Decision Height is eight hundred eighty-four feet. I retard the power levers to idle. Pre-landing checks complete. Flaps at one-seven. We started down. Precipitation on the windshield. Outside air temp below freezing. Confirmed anti-ice “On.” At DEPRE, the Final Approach Fix, I call for “Gear down,” then request the “Landing” checklist. Next, “Flaps twenty-eight,” and adjust the power levers to maintain VRef plus ten knots. The FO is dividing his attention between looking ahead through the windshield and checking his HSI, airspeed, and altimeter. I was on the gauges. My eyes darted across my side of the panel: artificial horizon; HSI; altimeter; artificial horizon again; airspeed; HSI again. Correcting. Kept my scan going. Rate of descent six hundred feet per minute. Steady. Gusts buffeting us. Scanning the instruments. Crabbing to the right. Correcting. Bracketing the heading to stay on the localizer. The FO makes his first call-out, “One thousand.” He was staring intently out the windshield, pausing only to shift his eyes to read his instruments. No ground contact or runway yet. Ceiling was supposed to be five hundred feet above ground level, or one thousand two hundred feet on the altimeter, but so far 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame only wet, gray nothingness illuminated by our landing lights. We are on localizer and glide slope. Speed is good. Descent rate good. Continuing. If we do not see the runway at minimums, we will go missed and sort this out. About 2.5 miles to the runway threshold. If you are wondering, my hands and forehead were dry. I did not feel relaxed – but I was not nervous. I felt alert and ready - and alive. One of the things I like best about flying is how it focuses your concentration. An ILS approach to minimums will do that. All of my senses were fully engaged. I have done this before; I am good at it. Hours and experience make a large difference in comfort level and confidence. I was ready to land or, if the runway did not appear in front of us at DH, I was prepared to go missed. Our training, standardization of procedures, and experience made both options equally possible and safe. “Two hundred,” the First Officer calls out. “One hundred . . . .” Then, “Runway in sight. Minimums.” I looked up

SHORT STORY from the panel and appearing through the rain-and-sleet-spattered windshield were the approach lighting and runway. Lights were up full. We were on the centerline. Slightly lowered the right wing. Rocking a bit with the gusts. Careful. I do not want to pick up the wing. Over the runway, I pull the power levers to idle. Crabbing over the centerline, nose into the quartering winds, bleeding off airspeed. Now, pushing left rudder hard to straighten out and track the centerline. A moment later, the right mains screech, lightly bounce once, and then make solid contact with the pavement. The left mains quickly follow and plant firmly. Yoke full right. Hold the nose off. Hold it. Now, let it down on the runway centerline. I call “Flaps up” and draw the power levers back and up, over the detents, moving the props into reverse pitch. We slow quickly, forward momentum pressing us against our shoulder straps as each prop’s four big, rectangular blades push hard opposite the oncoming air. I do not need to touch the brakes. Up ahead, the turn off to the taxiway. Despite wet, slick conditions, we will easily make the exit. For a second, I think to myself, “My dad would be proud.” There was a delay to our departure from GRB, as the ground crew addressed a minor mechanical issue with a cargo door latch. NCA owed much to the ramp agents, dispatchers, and ground personnel for our enviable “on time” record. Weather forecast now says conditions are improving. Low clouds and precipitation will move off to the east within the hour. We were on to Menominee, Escanaba, and Marquette, arriving MQT at 1230. To save time, we called ahead to the ramp agent at MQT and put in our orders for malts and cheeseburgers at our favorite local restaurant. Lunch at MQT will be quick, but still time enough to eat, laugh, and tell a few stories or discuss the news of the day. We will depart Marquette at 1335. For the return legs, we will make stops again at Escanaba, Green Bay, and Milwaukee, arriving O’Hare at about 1845. If you are counting, in a mix of VMC and IMC conditions, that is twelve takeoffs and landings. One instrument approach to minimums. With vectors and some headwinds, about six hours and forty-five minutes of actual flying time in twelve hours. All in a day’s work. I was rudely awakened by a lot of alarm clocks over the years. I went on to have a satisfying career in the airline business, despite competition, management shake-ups, mergers, and the sometimes fickle flying habits of the public, retiring as a senior captain on a Northwest Airlines DC-10. Just for fun on weekends, I flew Lockheed C-130s for the USAF Reserve’s 440th Airlift Wing out of Mitchell Field in Milwaukee. Shutting the big Allison turbines down on the ramp at ORD, I sat in the cockpit for a moment, watching out my side window as the four squared-off paddle blades spin down and slowly stop turning. The night sky was clear, cold, and black, with stars beginning to shine through wispy streaks of high cirrus clouds. I smile, remembering something a wise old NCA captain once said to me at the end of a long and trying day when I was starting out. “Cheated death again,” he joked. We both laughed. Every day since I started flying, I was always willing and happy to do that. * * * * * * * * [Dean Zakos learned to fly at Batten Field in Racine (KRAC) and at the Westosha airport in Westosha (5K6). Dean was born in Fond du Lac, and currently lives in Madison. He is a member of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), the EAA, and several local chapters of the EAA. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin— Madison, and he has a law degree from Marquette University Law School. His recent book, Laughing with the Wind: Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot (Square Peg Books, 2019), is available at Amazon and at Barnes & Noble.] 9 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021

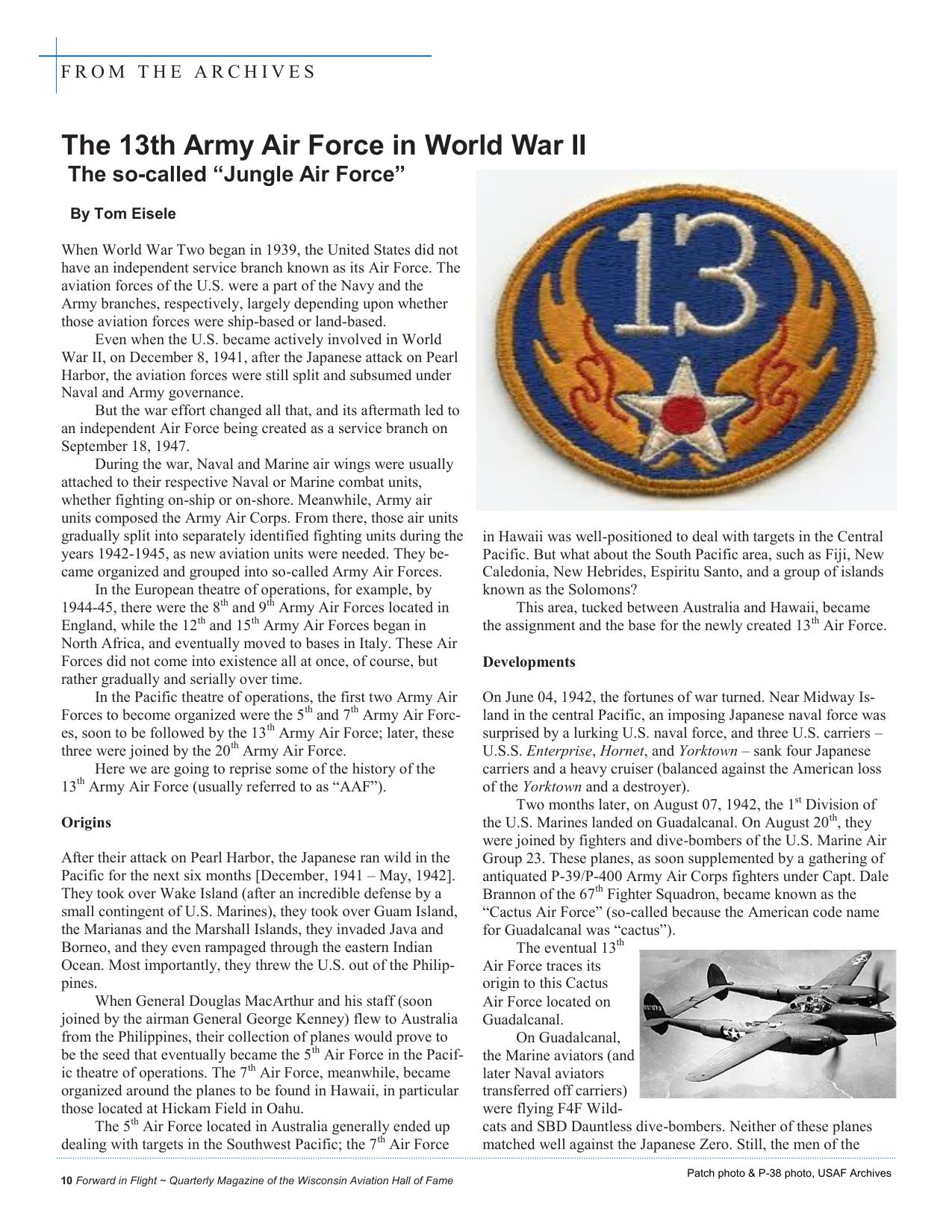

FROM THE ARCHIVES The 13th Army Air Force in World War II The so-called “Jungle Air Force” By Tom Eisele When World War Two began in 1939, the United States did not have an independent service branch known as its Air Force. The aviation forces of the U.S. were a part of the Navy and the Army branches, respectively, largely depending upon whether those aviation forces were ship-based or land-based. Even when the U.S. became actively involved in World War II, on December 8, 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the aviation forces were still split and subsumed under Naval and Army governance. But the war effort changed all that, and its aftermath led to an independent Air Force being created as a service branch on September 18, 1947. During the war, Naval and Marine air wings were usually attached to their respective Naval or Marine combat units, whether fighting on-ship or on-shore. Meanwhile, Army air units composed the Army Air Corps. From there, those air units gradually split into separately identified fighting units during the years 1942-1945, as new aviation units were needed. They became organized and grouped into so-called Army Air Forces. In the European theatre of operations, for example, by 1944-45, there were the 8th and 9th Army Air Forces located in England, while the 12th and 15th Army Air Forces began in North Africa, and eventually moved to bases in Italy. These Air Forces did not come into existence all at once, of course, but rather gradually and serially over time. In the Pacific theatre of operations, the first two Army Air Forces to become organized were the 5th and 7th Army Air Forces, soon to be followed by the 13th Army Air Force; later, these three were joined by the 20th Army Air Force. Here we are going to reprise some of the history of the 13th Army Air Force (usually referred to as “AAF”). Origins After their attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese ran wild in the Pacific for the next six months [December, 1941 – May, 1942]. They took over Wake Island (after an incredible defense by a small contingent of U.S. Marines), they took over Guam Island, the Marianas and the Marshall Islands, they invaded Java and Borneo, and they even rampaged through the eastern Indian Ocean. Most importantly, they threw the U.S. out of the Philippines. When General Douglas MacArthur and his staff (soon joined by the airman General George Kenney) flew to Australia from the Philippines, their collection of planes would prove to be the seed that eventually became the 5th Air Force in the Pacific theatre of operations. The 7th Air Force, meanwhile, became organized around the planes to be found in Hawaii, in particular those located at Hickam Field in Oahu. The 5th Air Force located in Australia generally ended up dealing with targets in the Southwest Pacific; the 7 th Air Force 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame in Hawaii was well-positioned to deal with targets in the Central Pacific. But what about the South Pacific area, such as Fiji, New Caledonia, New Hebrides, Espiritu Santo, and a group of islands known as the Solomons? This area, tucked between Australia and Hawaii, became the assignment and the base for the newly created 13 th Air Force. Developments On June 04, 1942, the fortunes of war turned. Near Midway Island in the central Pacific, an imposing Japanese naval force was surprised by a lurking U.S. naval force, and three U.S. carriers – U.S.S. Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown – sank four Japanese carriers and a heavy cruiser (balanced against the American loss of the Yorktown and a destroyer). Two months later, on August 07, 1942, the 1st Division of the U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal. On August 20 th, they were joined by fighters and dive-bombers of the U.S. Marine Air Group 23. These planes, as soon supplemented by a gathering of antiquated P-39/P-400 Army Air Corps fighters under Capt. Dale Brannon of the 67th Fighter Squadron, became known as the “Cactus Air Force” (so-called because the American code name for Guadalcanal was “cactus”). The eventual 13th Air Force traces its origin to this Cactus Air Force located on Guadalcanal. On Guadalcanal, the Marine aviators (and later Naval aviators transferred off carriers) were flying F4F Wildcats and SBD Dauntless dive-bombers. Neither of these planes matched well against the Japanese Zero. Still, the men of the Patch photo & P-38 photo, USAF Archives

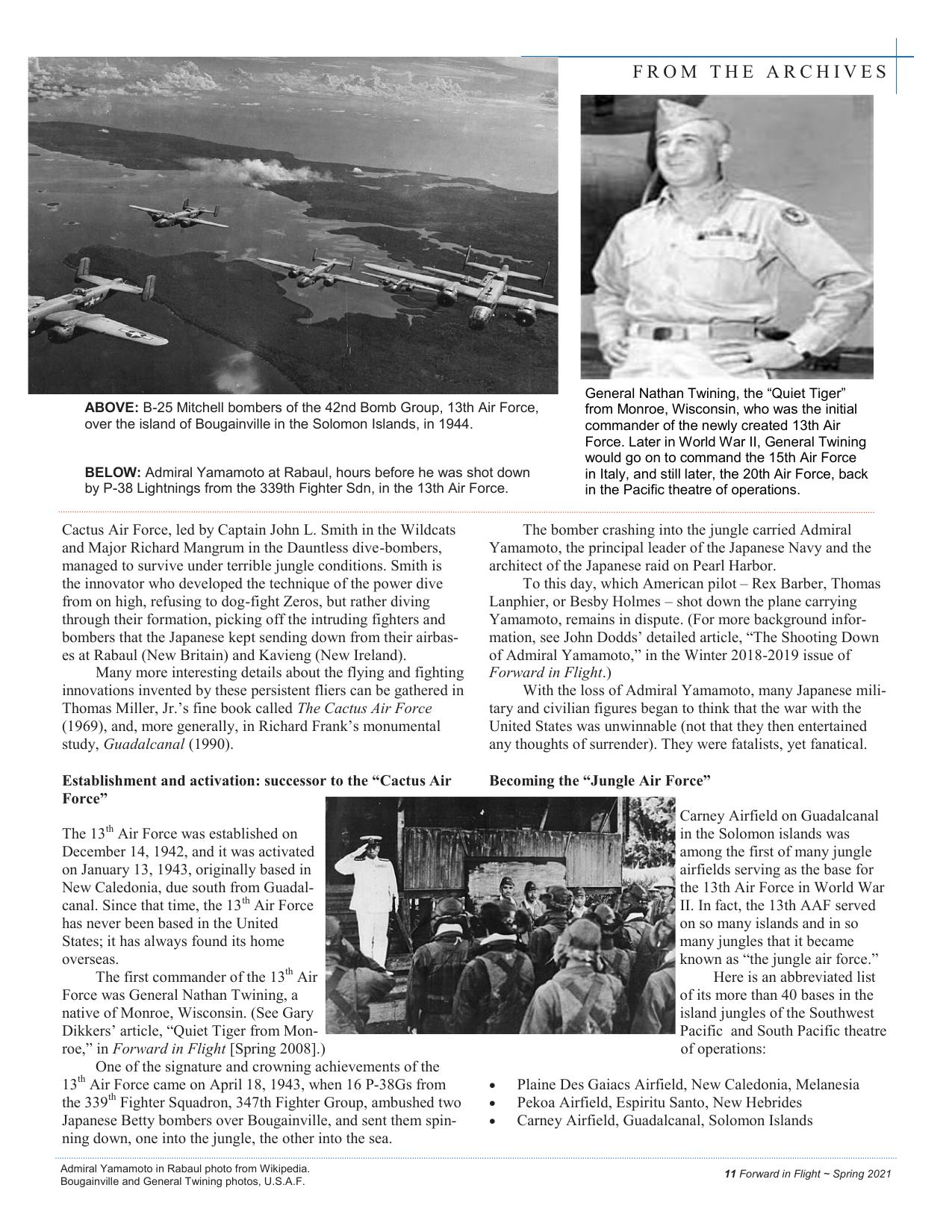

FROM THE ARCHIVES ABOVE: B-25 Mitchell bombers of the 42nd Bomb Group, 13th Air Force, over the island of Bougainville in the Solomon Islands, in 1944. BELOW: Admiral Yamamoto at Rabaul, hours before he was shot down by P-38 Lightnings from the 339th Fighter Sdn, in the 13th Air Force. General Nathan Twining, the “Quiet Tiger” from Monroe, Wisconsin, who was the initial commander of the newly created 13th Air Force. Later in World War II, General Twining would go on to command the 15th Air Force in Italy, and still later, the 20th Air Force, back in the Pacific theatre of operations. Cactus Air Force, led by Captain John L. Smith in the Wildcats and Major Richard Mangrum in the Dauntless dive-bombers, managed to survive under terrible jungle conditions. Smith is the innovator who developed the technique of the power dive from on high, refusing to dog-fight Zeros, but rather diving through their formation, picking off the intruding fighters and bombers that the Japanese kept sending down from their airbases at Rabaul (New Britain) and Kavieng (New Ireland). Many more interesting details about the flying and fighting innovations invented by these persistent fliers can be gathered in Thomas Miller, Jr.’s fine book called The Cactus Air Force (1969), and, more generally, in Richard Frank’s monumental study, Guadalcanal (1990). The bomber crashing into the jungle carried Admiral Yamamoto, the principal leader of the Japanese Navy and the architect of the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor. To this day, which American pilot – Rex Barber, Thomas Lanphier, or Besby Holmes – shot down the plane carrying Yamamoto, remains in dispute. (For more background information, see John Dodds’ detailed article, “The Shooting Down of Admiral Yamamoto,” in the Winter 2018-2019 issue of Forward in Flight.) With the loss of Admiral Yamamoto, many Japanese military and civilian figures began to think that the war with the United States was unwinnable (not that they then entertained any thoughts of surrender). They were fatalists, yet fanatical. Establishment and activation: successor to the “Cactus Air Force” Becoming the “Jungle Air Force” The 13th Air Force was established on December 14, 1942, and it was activated on January 13, 1943, originally based in New Caledonia, due south from Guadalcanal. Since that time, the 13th Air Force has never been based in the United States; it has always found its home overseas. The first commander of the 13th Air Force was General Nathan Twining, a native of Monroe, Wisconsin. (See Gary Dikkers’ article, “Quiet Tiger from Monroe,” in Forward in Flight [Spring 2008].) One of the signature and crowning achievements of the 13th Air Force came on April 18, 1943, when 16 P-38Gs from the 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, ambushed two Japanese Betty bombers over Bougainville, and sent them spinning down, one into the jungle, the other into the sea. Admiral Yamamoto in Rabaul photo from Wikipedia. Bougainville and General Twining photos, U.S.A.F. Carney Airfield on Guadalcanal in the Solomon islands was among the first of many jungle airfields serving as the base for the 13th Air Force in World War II. In fact, the 13th AAF served on so many islands and in so many jungles that it became known as “the jungle air force.” Here is an abbreviated list of its more than 40 bases in the island jungles of the Southwest Pacific and South Pacific theatre of operations: • • • Plaine Des Gaiacs Airfield, New Caledonia, Melanesia Pekoa Airfield, Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides Carney Airfield, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands 11 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021

FROM THE ARCHIVES • • • • • Momote Airfield, Los Negros, Admiralty Islands Hollandia, New Guinea Hollandia Airfield, Netherlands East Indies Wama Airfield, Morotai, Netherlands East Indies Clark Airfield, Luzon, Philippines This list will help to indicate the tremendous distances and various jungle locales inhabited by members of the 13th Air Force. Missions and Targets and Campaigns (selective list) Once Guadalcanal was won (by February 1943), the focus of the 13th Air Force became to subdue the rest of the Solomon Islands. For the remainder of 1943, the planes of the 13th Air Force worked over the Japanese airbases and sea bases in those islands, paving the way for eventual landings, especially in New Georgia and Bougainville. By November-December, 1943, those islands were in the hands of (or under the control of) the American forces. It also should be kept in mind that these farflung operations against various islands were coordinated with bombing efforts by the Fifth Air Force. Both Air Forces were working in tandem. ABOVE: Patch from the Philippine Islands, where echelons of the 13th Air Force were based at Clark Field (circa 1944-45). LEFT: General Douglas MacArthur at Morotai on September 15, 1944, where the 13th Air Force was to be heavily engaged by the Japanese, who did not want to give it up as a base. Please note: This photo is NOT the more famous “I Shall Return” photo from the later invasion of the Philippines on October 20, 1944. Then came Rabaul, which was the prime Japanese sea base and airbase in the Southwest and South Pacific, second in importance only to the Japanese sea base and fortress at Truk island. The 13th Air Force took turns with the Fifth Air Force in systematically bombing the series of installations at and around Rabaul, leaving it isolated and essentially useless. The damage done by the relentless bombing (from December, 1943, to February, 1944) made it unnecessary to land any troops at Rabaul; consequently, it was bypassed by American forces and left to rot on the vine. Rabaul was neutralized for the remainder of the war. In mid-1944, the main operations of the 13th Air Force switched to some central Pacific islands: Truk, Woleai, Yap, and the Palau Islands. (Command of the 13th AAF also had switched, to General Hubert Harmon.) The idea was that, in this way, we could suppress Japanese forces while simultaneously securing the approaches to the Philippines (in anticipation of the ensuing assault upon those islands by MacArthur’s army group). 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame In May-June, 1944, the incessant attacks on these strings of islands were prosecuted vigorously, eventually battering the Japanese defenders into submission. At this stage, the 13th Air Force was actually absorbed into a newly created “Far East Air Service Command” (on June 15, 1944). This amalgamation recognized that the Fifth, 7th, and 13th Air Forces were all committed to ending the reign of terror by the Japanese, and certain efficiencies were achieved by bringing these three Air Forces and unifying them within one command. Major offensive campaigns remained to be conducted against the Japanese positions in New Guinea and Morotai (in the Netherlands East Indies) from June to September, 1944, and finally in the Philippine islands (October, 1944). Endemic Problems and Shortages for the 13th Air Force When you consider the constant island-hopping nature of this air campaign, it becomes reasonably clear that there would be recurring problems. Trying to prosecute air operations over such a vast territory would naturally present several problems: • First, the distances covered were daunting. Since all of the operations required flights over ocean waters, engine failures or fuel leaks meant a water landing and likely loss of life. In this respect, small failures sometimes turned into life-or-death situations. • Second, the tropics were rank with malarial mosquitoes, dengue fever, dysentery, and what generically was referred to as “the crud.” Personal health and sanitation suffered. General Douglas MacArthur on Morotai, U.S. Army photo

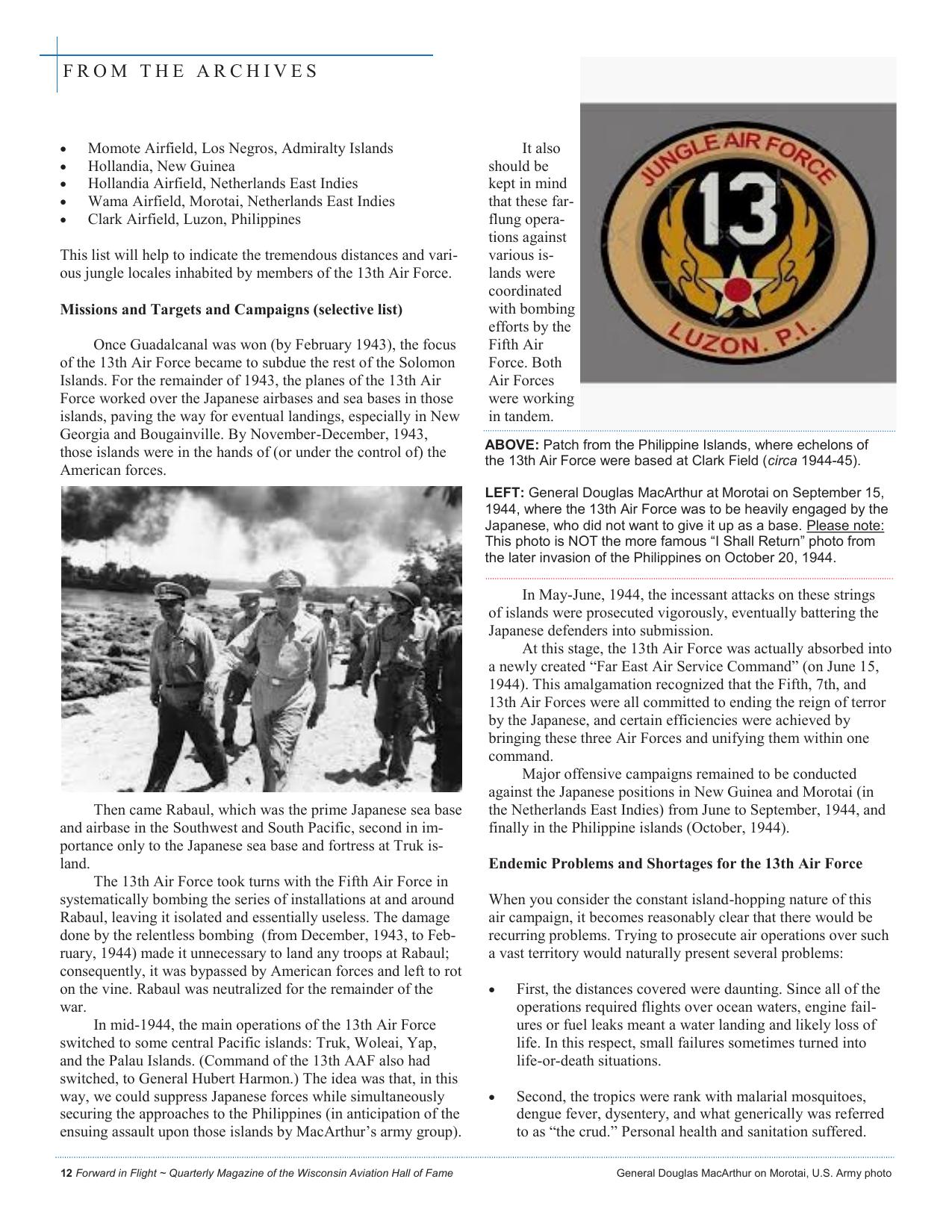

FROM THE ARCHIVES Statistical Record of the 13th Army Air Force in World War II: Total Combat Sorties Flown: 97,038 Total Bomb Tonnage Dropped on Targets: 61,929 Total Ship Tonnage Sunk: 569,070 Total 13th AAF Aircraft Lost in Combat: Total Enemy Aircraft Destroyed: 1,439 490 [Map, From Fiji Through the Philippines with the 13th Air Force] • Third, because of the incredible distances involved and the fact that supplies had to be brought in by ship or by air — there were no highways to be used — lack of equipment, lack of ammo, lack of medicine, and lack of nutritious food were prevalent problems. • Fourth, the U.S. had pledged to Winston Churchill in the UK that we would follow a “Europe First” strategy. That meant that the European theatre of operations got first priority on supplies and equipment, not the Pacific. Hap Arnold was the General who presided over the Army Air Corps, and he rigorously enforced this “Europe First” prioritization. Here is one example of its cost to American flyers in the Pacific. Admiral John McCain proposed that P-38 Lightnings be shipped to Benjamin Lippincott, From Fiji through the Philippines with the 13th Air Force (1948). Copyright 1948 U.S. Air Forces Aid Society. All rights reserved. the flyers in Guadalcanal, making it a “sinkhole” for Japanese ships and planes. General Arnold refused to release the P-38s to the Pacific. This, despite the fact that only P-38s had the range and fuel efficiency, and the twin engines, necessary for survival and success in this vast oceanic theatre of operations. In the end, however, the 13th Army Air Force proved equal to its task and its mission. As the map (above) attests, with this conflict covering a significant portion of the globe, the 13th Air Force had a daunting array of assignments. No matter. Whenever called upon, the members of the 13th AAF answered the call. 13 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021

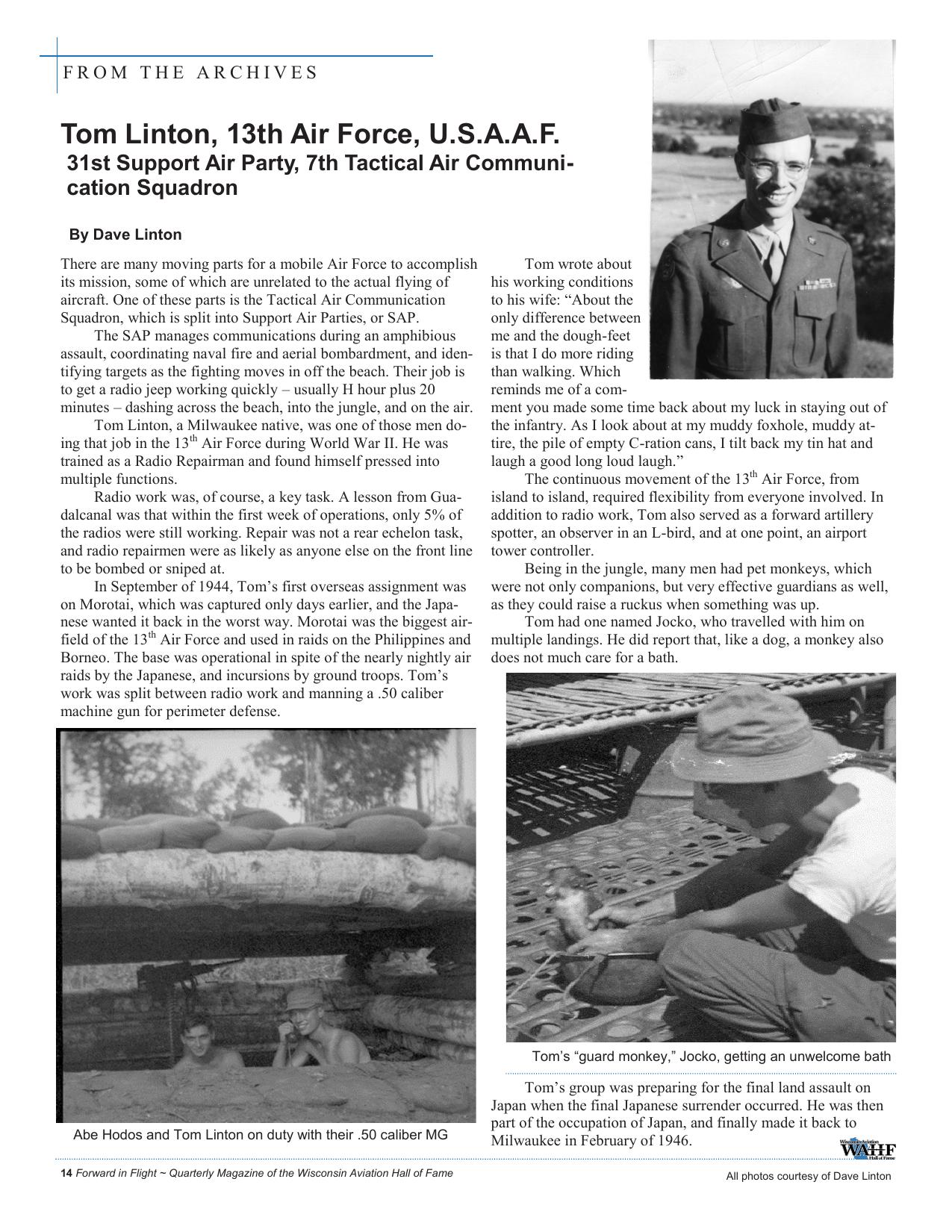

FROM THE ARCHIVES Tom Linton, 13th Air Force, U.S.A.A.F. 31st Support Air Party, 7th Tactical Air Communication Squadron By Dave Linton There are many moving parts for a mobile Air Force to accomplish its mission, some of which are unrelated to the actual flying of aircraft. One of these parts is the Tactical Air Communication Squadron, which is split into Support Air Parties, or SAP. The SAP manages communications during an amphibious assault, coordinating naval fire and aerial bombardment, and identifying targets as the fighting moves in off the beach. Their job is to get a radio jeep working quickly – usually H hour plus 20 minutes – dashing across the beach, into the jungle, and on the air. Tom Linton, a Milwaukee native, was one of those men doing that job in the 13th Air Force during World War II. He was trained as a Radio Repairman and found himself pressed into multiple functions. Radio work was, of course, a key task. A lesson from Guadalcanal was that within the first week of operations, only 5% of the radios were still working. Repair was not a rear echelon task, and radio repairmen were as likely as anyone else on the front line to be bombed or sniped at. In September of 1944, Tom’s first overseas assignment was on Morotai, which was captured only days earlier, and the Japanese wanted it back in the worst way. Morotai was the biggest airfield of the 13th Air Force and used in raids on the Philippines and Borneo. The base was operational in spite of the nearly nightly air raids by the Japanese, and incursions by ground troops. Tom’s work was split between radio work and manning a .50 caliber machine gun for perimeter defense. Tom wrote about his working conditions to his wife: “About the only difference between me and the dough-feet is that I do more riding than walking. Which reminds me of a comment you made some time back about my luck in staying out of the infantry. As I look about at my muddy foxhole, muddy attire, the pile of empty C-ration cans, I tilt back my tin hat and laugh a good long loud laugh.” The continuous movement of the 13th Air Force, from island to island, required flexibility from everyone involved. In addition to radio work, Tom also served as a forward artillery spotter, an observer in an L-bird, and at one point, an airport tower controller. Being in the jungle, many men had pet monkeys, which were not only companions, but very effective guardians as well, as they could raise a ruckus when something was up. Tom had one named Jocko, who travelled with him on multiple landings. He did report that, like a dog, a monkey also does not much care for a bath. Tom’s “guard monkey,” Jocko, getting an unwelcome bath Abe Hodos and Tom Linton on duty with their .50 caliber MG 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Tom’s group was preparing for the final land assault on Japan when the final Japanese surrender occurred. He was then part of the occupation of Japan, and finally made it back to Milwaukee in February of 1946. All photos courtesy of Dave Linton

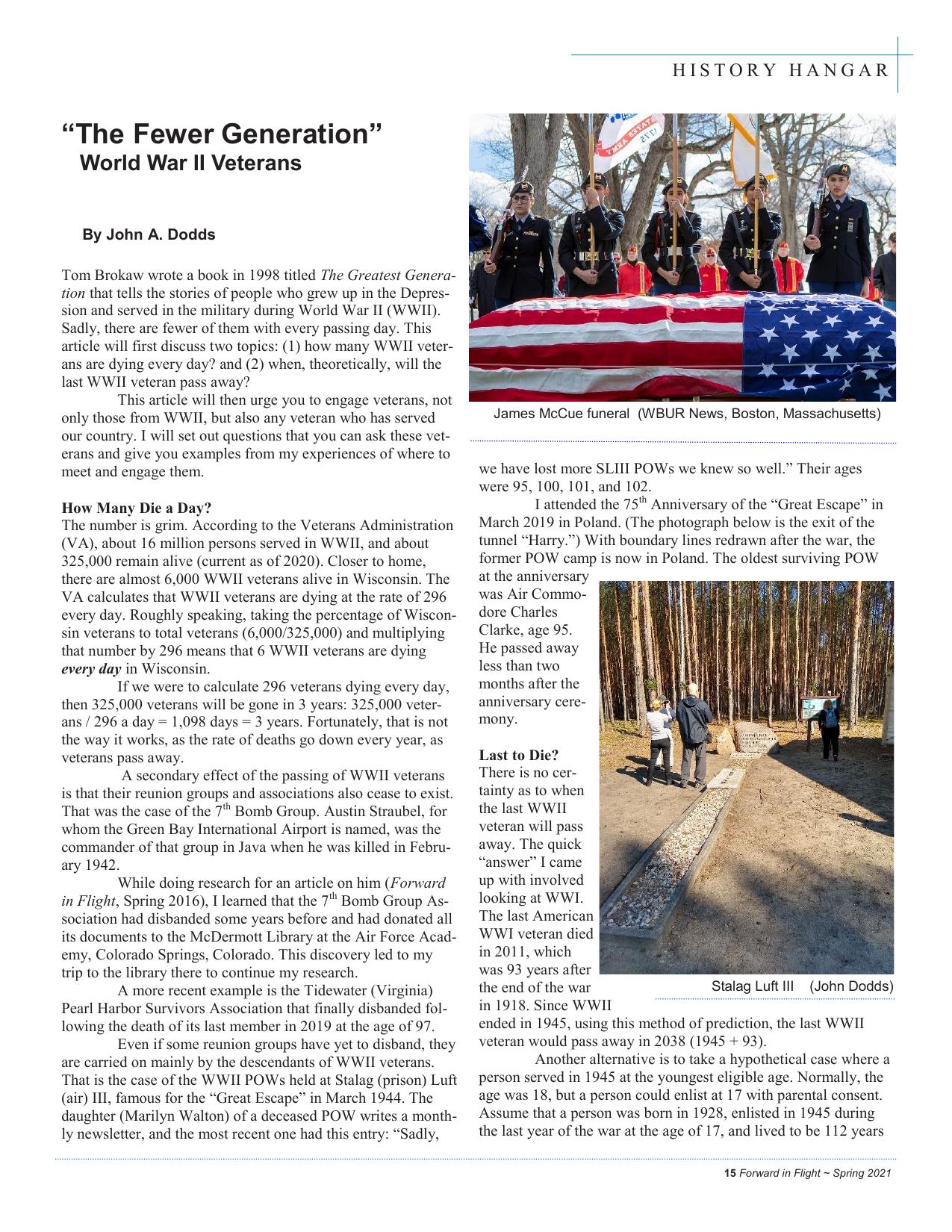

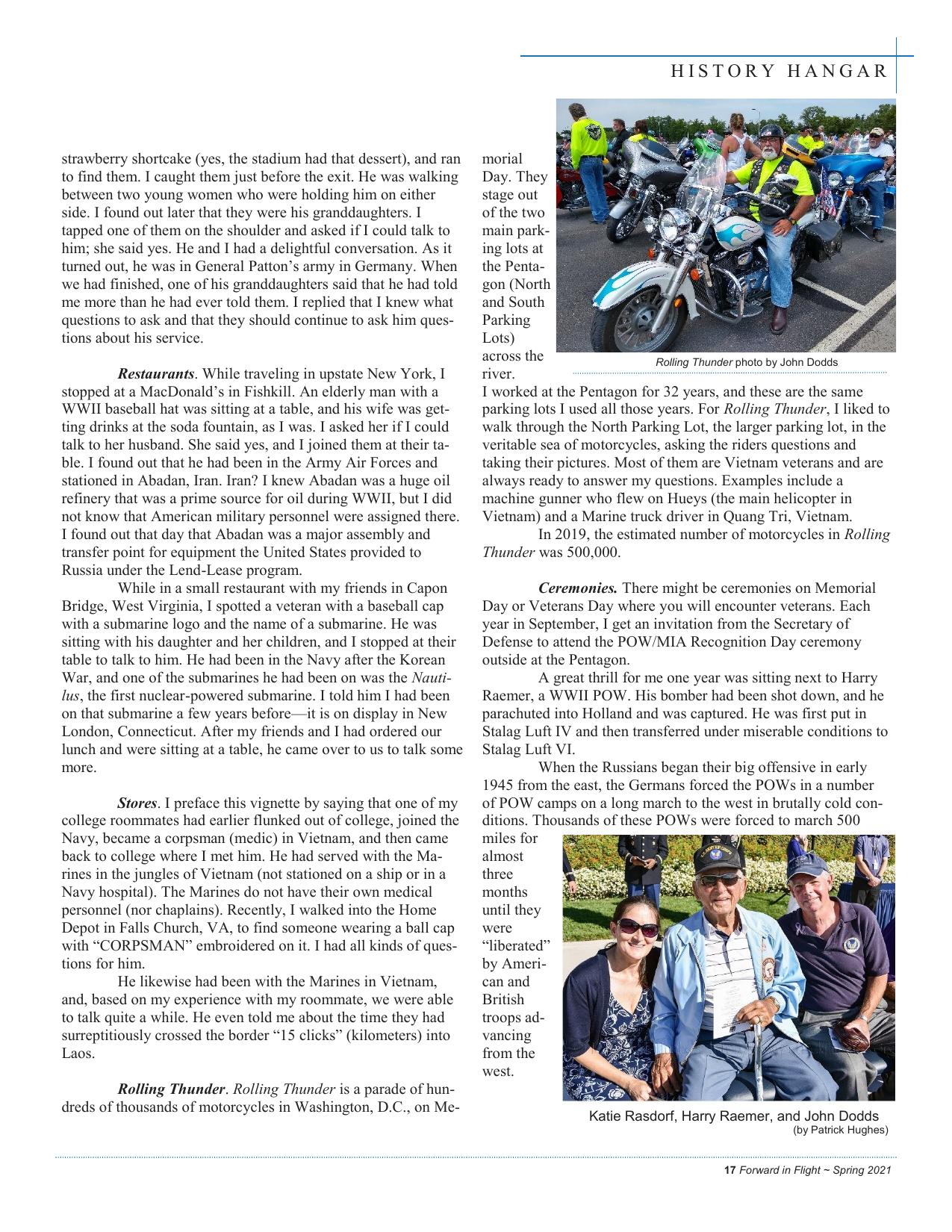

HISTORY HANGAR “The Fewer Generation” World War II Veterans By John A. Dodds Tom Brokaw wrote a book in 1998 titled The Greatest Generation that tells the stories of people who grew up in the Depression and served in the military during World War II (WWII). Sadly, there are fewer of them with every passing day. This article will first discuss two topics: (1) how many WWII veterans are dying every day? and (2) when, theoretically, will the last WWII veteran pass away? This article will then urge you to engage veterans, not only those from WWII, but also any veteran who has served our country. I will set out questions that you can ask these veterans and give you examples from my experiences of where to meet and engage them. How Many Die a Day? The number is grim. According to the Veterans Administration (VA), about 16 million persons served in WWII, and about 325,000 remain alive (current as of 2020). Closer to home, there are almost 6,000 WWII veterans alive in Wisconsin. The VA calculates that WWII veterans are dying at the rate of 296 every day. Roughly speaking, taking the percentage of Wisconsin veterans to total veterans (6,000/325,000) and multiplying that number by 296 means that 6 WWII veterans are dying every day in Wisconsin. If we were to calculate 296 veterans dying every day, then 325,000 veterans will be gone in 3 years: 325,000 veterans / 296 a day = 1,098 days = 3 years. Fortunately, that is not the way it works, as the rate of deaths go down every year, as veterans pass away. A secondary effect of the passing of WWII veterans is that their reunion groups and associations also cease to exist. That was the case of the 7th Bomb Group. Austin Straubel, for whom the Green Bay International Airport is named, was the commander of that group in Java when he was killed in February 1942. While doing research for an article on him (Forward in Flight, Spring 2016), I learned that the 7th Bomb Group Association had disbanded some years before and had donated all its documents to the McDermott Library at the Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado. This discovery led to my trip to the library there to continue my research. A more recent example is the Tidewater (Virginia) Pearl Harbor Survivors Association that finally disbanded following the death of its last member in 2019 at the age of 97. Even if some reunion groups have yet to disband, they are carried on mainly by the descendants of WWII veterans. That is the case of the WWII POWs held at Stalag (prison) Luft (air) III, famous for the “Great Escape” in March 1944. The daughter (Marilyn Walton) of a deceased POW writes a monthly newsletter, and the most recent one had this entry: “Sadly, James McCue funeral (WBUR News, Boston, Massachusetts) we have lost more SLIII POWs we knew so well.” Their ages were 95, 100, 101, and 102. I attended the 75th Anniversary of the “Great Escape” in March 2019 in Poland. (The photograph below is the exit of the tunnel “Harry.”) With boundary lines redrawn after the war, the former POW camp is now in Poland. The oldest surviving POW at the anniversary was Air Commodore Charles Clarke, age 95. He passed away less than two months after the anniversary ceremony. Last to Die? There is no certainty as to when the last WWII veteran will pass away. The quick “answer” I came up with involved looking at WWI. The last American WWI veteran died in 2011, which was 93 years after Stalag Luft III (John Dodds) the end of the war in 1918. Since WWII ended in 1945, using this method of prediction, the last WWII veteran would pass away in 2038 (1945 + 93). Another alternative is to take a hypothetical case where a person served in 1945 at the youngest eligible age. Normally, the age was 18, but a person could enlist at 17 with parental consent. Assume that a person was born in 1928, enlisted in 1945 during the last year of the war at the age of 17, and lived to be 112 years 15 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021

HISTORY HANGAR old (as one veteran did). This last WWII veteran would pass away in 2040 (1928 + 112). According to a statistical model of the Veterans Administration (VA), the last WWII veteran will die in 2043. The time differences between my simple alternatives (2038 and 2040) are quite comparable to the VA’s statistical analysis (2043). In any case, time is running out—not only for the veterans themselves, but also for us to engage with them. No Relatives It is not uncommon for an elderly WWII veteran to die without any surviving relatives. That was the case of James McCue, age 97, of Lawrence, Massachusetts, who long outlived his wife and had no other relatives. Nevertheless, hundreds of people showed up to attend his military funeral (photo from his funeral at the beginning of this article.) It can also be the case for a Vietnam veteran, like Stanley Stolz, age 73, of Bennington, Nebraska. Hundreds of people from the community attended his funeral (photo below). Stanley Stolz funeral (Fox News) Engaging a WWII Veteran If the youngest WWII veteran alive today was born in 1928 (see discussion above), that person would be 93 years old today. And that is the youngest veteran! If there is no one in your family who is a WWII veteran to talk to, then what can you do? I will give you a number of my experiences. Every experience involves taking the initiative to talk to a veteran. The examples I will give include not only veterans of WWII but also veterans from later times as well. How do you recognize a veteran? Veterans are often recognized in public by the typical ball caps they wear with embroidered logos like “World War II Veteran,” “Vietnam Veteran,” or “U.S. Army (Retired).” If the veteran served at sea in the Navy, the cap may have the name of the ship and perhaps an embroidered shape, such as a submarine. Veterans might also be wearing other apparel that indicates they are veterans. For example, they might be wearing an old field jacket. Or they might be wearing an old uniform at some type of 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ceremony. Or, they just might be wearing civilian clothes when you meet them, and they divulge that they are a veteran. What to Ask? I usually begin by asking what years the veteran served even though the cap might say “World War II Veteran.” I next ask what military branch, place(s) of service, unit(s), and occupational specialty. I also ask what the veteran did after his/her service. You will most likely have follow-up John “Lucky” Luckadoo questions depending on (John Dodds) the answers. But how do you first engage a veteran whom you see and do not know? It is actually quite simple: just go up to the veteran and begin by saying something like this: “I see that you were in WWII, what years were you in?” This approach has never failed me. My kids know that I like to talk to veterans. They know that I can get distracted from whatever mission we are on. I spotted a veteran one day on a shopping trip with my daughter Hayley. Seeing a WWII veteran in the store, I told her that I was going to talk to him. Knowing that that conversation would take some time, she moaned, “Dad, nooooo!” I was undeterred. Where do you meet a Veteran? Air Shows. In May 2018, I attended the air show at Wright-Patterson A.F.B., Ohio, following the “reveal” of the restored WWII B-17 bomber “Memphis Belle” (Forward in Flight, Summer 2018). There were a number of WWII veterans there (some in wheelchairs). One was a B-17 pilot named John “Lucky” Luckadoo (pictured above right). Today, he is 99 years old. He completed (I should say “survived”) 25 missions with the 100 th Bomb Group (known as the “Bloody Hundreth” for its high losses of crew and aircraft), Stadiums. While at a baseball spring training game in Lakeland, Florida, with my older son Matthew, I spotted an elderly person wearing an embroidered WWII hat sitting a few rows ahead of us. My plan was to approach him when the game was over. However, he and his family got up and left after the fourth inning. After they left, I could not restrain myself any longer. I got up, told my son I would bring him back some

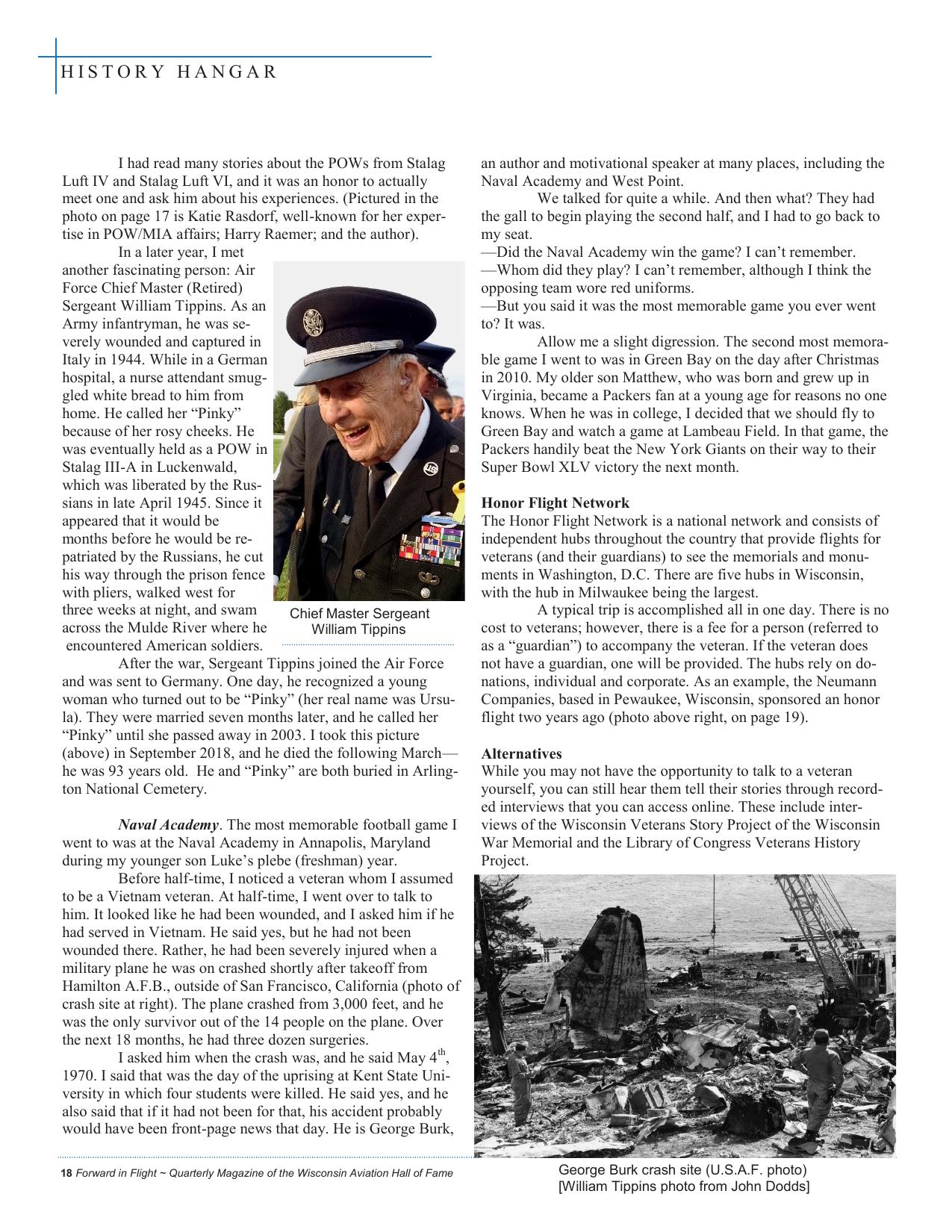

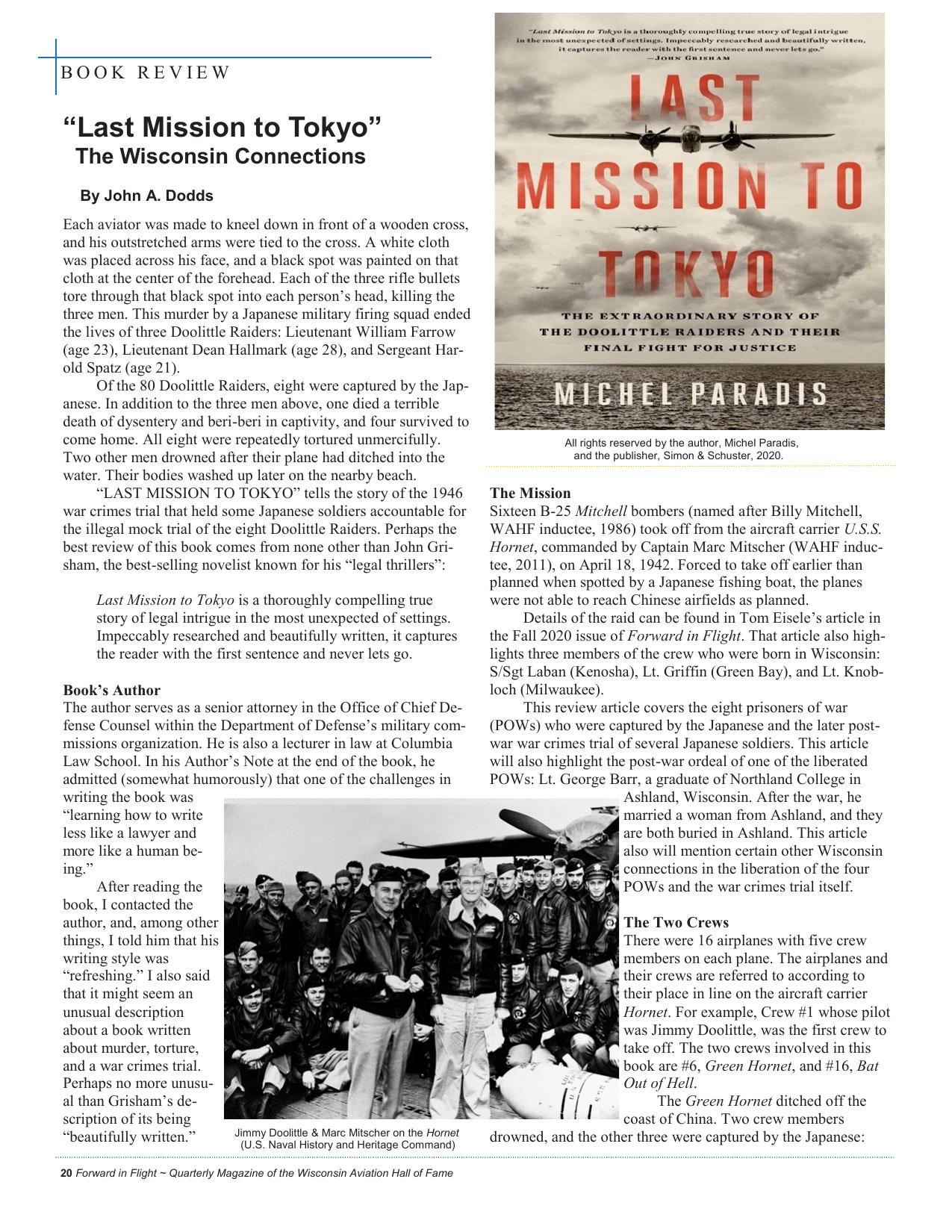

HISTORY HANGAR strawberry shortcake (yes, the stadium had that dessert), and ran to find them. I caught them just before the exit. He was walking between two young women who were holding him on either side. I found out later that they were his granddaughters. I tapped one of them on the shoulder and asked if I could talk to him; she said yes. He and I had a delightful conversation. As it turned out, he was in General Patton’s army in Germany. When we had finished, one of his granddaughters said that he had told me more than he had ever told them. I replied that I knew what questions to ask and that they should continue to ask him questions about his service. Restaurants. While traveling in upstate New York, I stopped at a MacDonald’s in Fishkill. An elderly man with a WWII baseball hat was sitting at a table, and his wife was getting drinks at the soda fountain, as I was. I asked her if I could talk to her husband. She said yes, and I joined them at their table. I found out that he had been in the Army Air Forces and stationed in Abadan, Iran. Iran? I knew Abadan was a huge oil refinery that was a prime source for oil during WWII, but I did not know that American military personnel were assigned there. I found out that day that Abadan was a major assembly and transfer point for equipment the United States provided to Russia under the Lend-Lease program. While in a small restaurant with my friends in Capon Bridge, West Virginia, I spotted a veteran with a baseball cap with a submarine logo and the name of a submarine. He was sitting with his daughter and her children, and I stopped at their table to talk to him. He had been in the Navy after the Korean War, and one of the submarines he had been on was the Nautilus, the first nuclear-powered submarine. I told him I had been on that submarine a few years before—it is on display in New London, Connecticut. After my friends and I had ordered our lunch and were sitting at a table, he came over to us to talk some more. Stores. I preface this vignette by saying that one of my college roommates had earlier flunked out of college, joined the Navy, became a corpsman (medic) in Vietnam, and then came back to college where I met him. He had served with the Marines in the jungles of Vietnam (not stationed on a ship or in a Navy hospital). The Marines do not have their own medical personnel (nor chaplains). Recently, I walked into the Home Depot in Falls Church, VA, to find someone wearing a ball cap with “CORPSMAN” embroidered on it. I had all kinds of questions for him. He likewise had been with the Marines in Vietnam, and, based on my experience with my roommate, we were able to talk quite a while. He even told me about the time they had surreptitiously crossed the border “15 clicks” (kilometers) into Laos. Rolling Thunder. Rolling Thunder is a parade of hundreds of thousands of motorcycles in Washington, D.C., on Me- morial Day. They stage out of the two main parking lots at the Pentagon (North and South Parking Lots) across the Rolling Thunder photo by John Dodds river. I worked at the Pentagon for 32 years, and these are the same parking lots I used all those years. For Rolling Thunder, I liked to walk through the North Parking Lot, the larger parking lot, in the veritable sea of motorcycles, asking the riders questions and taking their pictures. Most of them are Vietnam veterans and are always ready to answer my questions. Examples include a machine gunner who flew on Hueys (the main helicopter in Vietnam) and a Marine truck driver in Quang Tri, Vietnam. In 2019, the estimated number of motorcycles in Rolling Thunder was 500,000. Ceremonies. There might be ceremonies on Memorial Day or Veterans Day where you will encounter veterans. Each year in September, I get an invitation from the Secretary of Defense to attend the POW/MIA Recognition Day ceremony outside at the Pentagon. A great thrill for me one year was sitting next to Harry Raemer, a WWII POW. His bomber had been shot down, and he parachuted into Holland and was captured. He was first put in Stalag Luft IV and then transferred under miserable conditions to Stalag Luft VI. When the Russians began their big offensive in early 1945 from the east, the Germans forced the POWs in a number of POW camps on a long march to the west in brutally cold conditions. Thousands of these POWs were forced to march 500 miles for almost three months until they were “liberated” by American and British troops advancing from the west. Katie Rasdorf, Harry Raemer, and John Dodds (by Patrick Hughes) 17 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021

HISTORY HANGAR I had read many stories about the POWs from Stalag Luft IV and Stalag Luft VI, and it was an honor to actually meet one and ask him about his experiences. (Pictured in the photo on page 17 is Katie Rasdorf, well-known for her expertise in POW/MIA affairs; Harry Raemer; and the author). In a later year, I met another fascinating person: Air Force Chief Master (Retired) Sergeant William Tippins. As an Army infantryman, he was severely wounded and captured in Italy in 1944. While in a German hospital, a nurse attendant smuggled white bread to him from home. He called her “Pinky” because of her rosy cheeks. He was eventually held as a POW in Stalag III-A in Luckenwald, which was liberated by the Russians in late April 1945. Since it appeared that it would be months before he would be repatriated by the Russians, he cut his way through the prison fence with pliers, walked west for three weeks at night, and swam Chief Master Sergeant across the Mulde River where he William Tippins encountered American soldiers. After the war, Sergeant Tippins joined the Air Force and was sent to Germany. One day, he recognized a young woman who turned out to be “Pinky” (her real name was Ursula). They were married seven months later, and he called her “Pinky” until she passed away in 2003. I took this picture (above) in September 2018, and he died the following March— he was 93 years old. He and “Pinky” are both buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Naval Academy. The most memorable football game I went to was at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland during my younger son Luke’s plebe (freshman) year. Before half-time, I noticed a veteran whom I assumed to be a Vietnam veteran. At half-time, I went over to talk to him. It looked like he had been wounded, and I asked him if he had served in Vietnam. He said yes, but he had not been wounded there. Rather, he had been severely injured when a military plane he was on crashed shortly after takeoff from Hamilton A.F.B., outside of San Francisco, California (photo of crash site at right). The plane crashed from 3,000 feet, and he was the only survivor out of the 14 people on the plane. Over the next 18 months, he had three dozen surgeries. I asked him when the crash was, and he said May 4th, 1970. I said that was the day of the uprising at Kent State University in which four students were killed. He said yes, and he also said that if it had not been for that, his accident probably would have been front-page news that day. He is George Burk, 18 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame an author and motivational speaker at many places, including the Naval Academy and West Point. We talked for quite a while. And then what? They had the gall to begin playing the second half, and I had to go back to my seat. —Did the Naval Academy win the game? I can’t remember. —Whom did they play? I can’t remember, although I think the opposing team wore red uniforms. —But you said it was the most memorable game you ever went to? It was. Allow me a slight digression. The second most memorable game I went to was in Green Bay on the day after Christmas in 2010. My older son Matthew, who was born and grew up in Virginia, became a Packers fan at a young age for reasons no one knows. When he was in college, I decided that we should fly to Green Bay and watch a game at Lambeau Field. In that game, the Packers handily beat the New York Giants on their way to their Super Bowl XLV victory the next month. Honor Flight Network The Honor Flight Network is a national network and consists of independent hubs throughout the country that provide flights for veterans (and their guardians) to see the memorials and monuments in Washington, D.C. There are five hubs in Wisconsin, with the hub in Milwaukee being the largest. A typical trip is accomplished all in one day. There is no cost to veterans; however, there is a fee for a person (referred to as a “guardian”) to accompany the veteran. If the veteran does not have a guardian, one will be provided. The hubs rely on donations, individual and corporate. As an example, the Neumann Companies, based in Pewaukee, Wisconsin, sponsored an honor flight two years ago (photo above right, on page 19). Alternatives While you may not have the opportunity to talk to a veteran yourself, you can still hear them tell their stories through recorded interviews that you can access online. These include interviews of the Wisconsin Veterans Story Project of the Wisconsin War Memorial and the Library of Congress Veterans History Project. George Burk crash site (U.S.A.F. photo) [William Tippins photo from John Dodds]

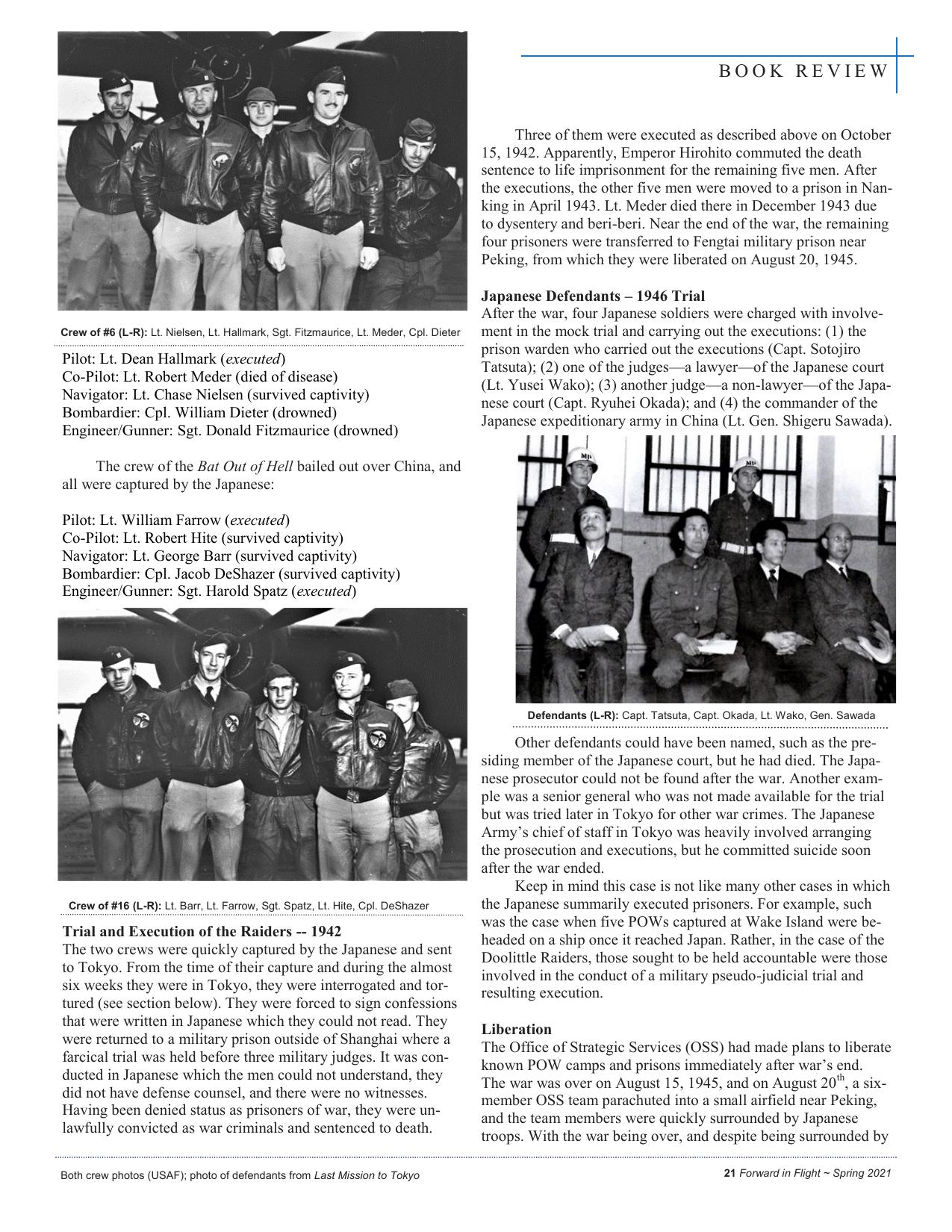

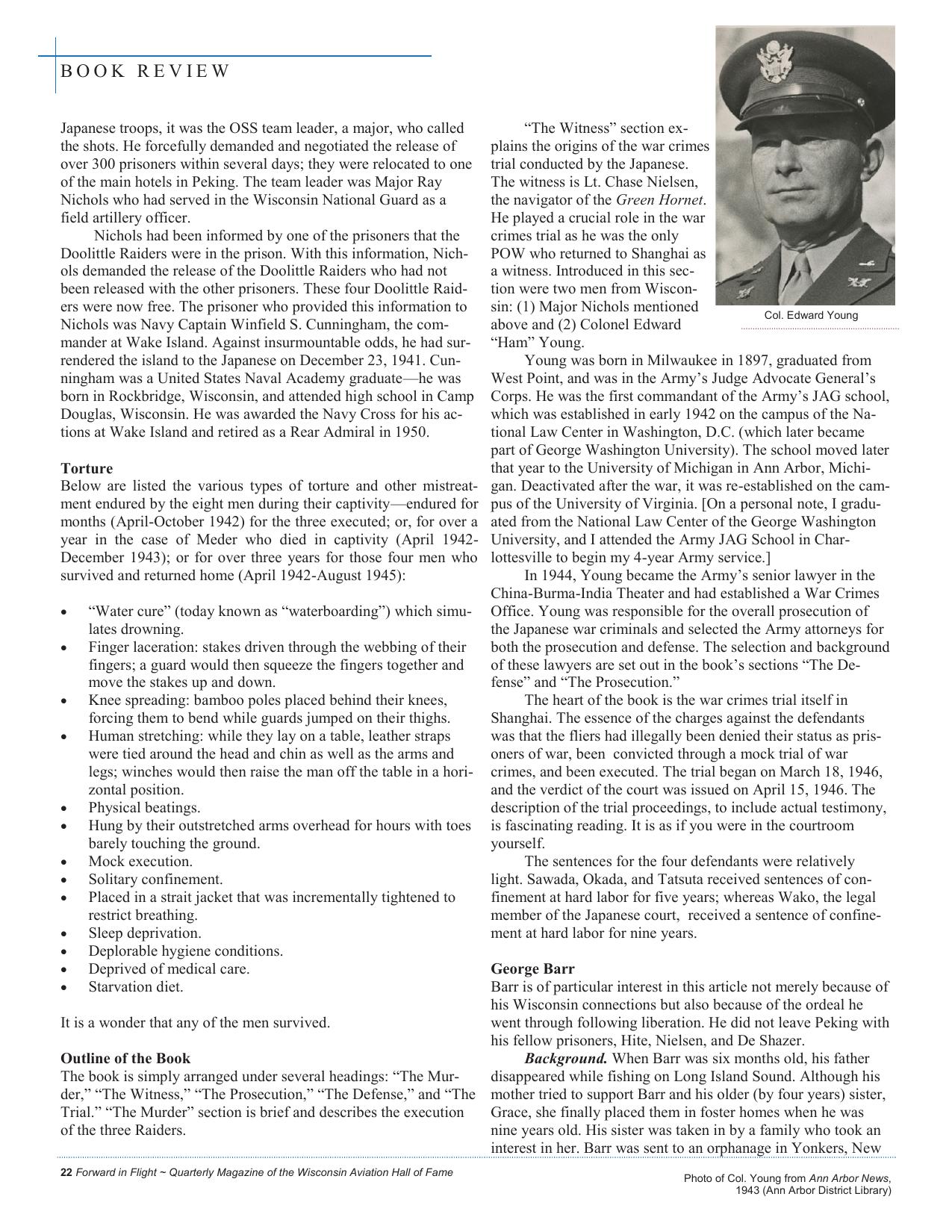

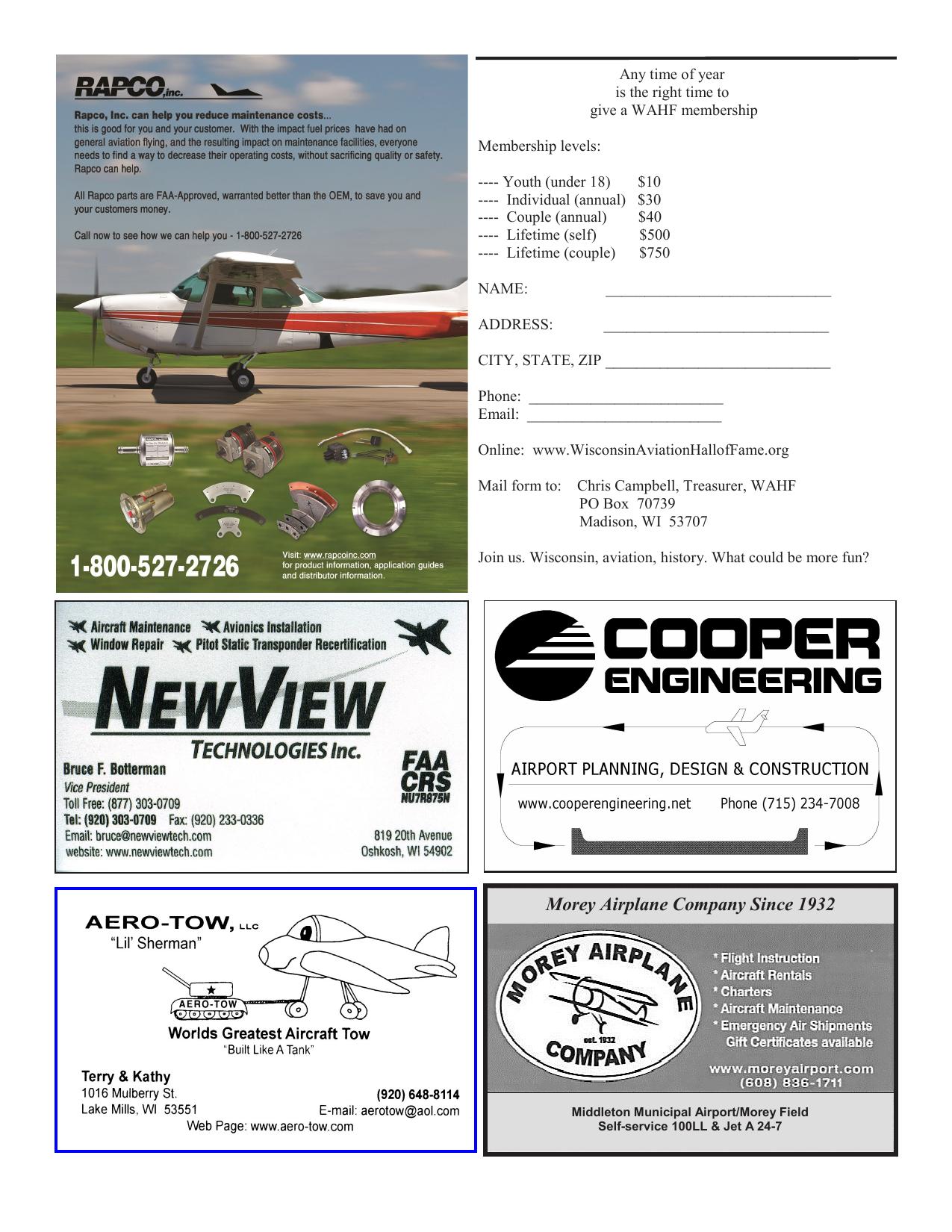

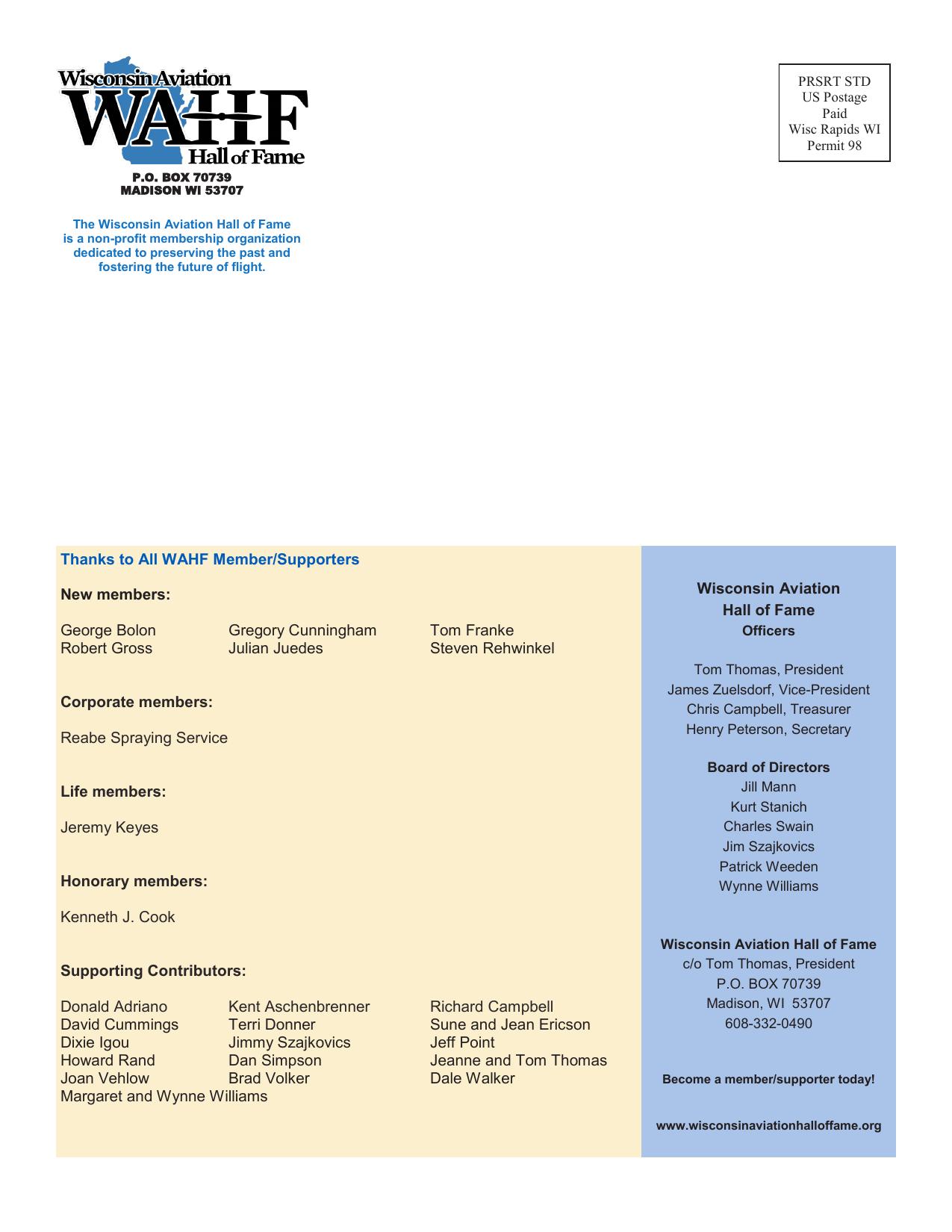

HISTORY HANGAR Wisconsin Honor Flight Medal of Honor Recipients The Congressional Medal of Honor is the highest award for valor in combat and is awarded to a military service member who “distinguishes himself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.” My interest in these individuals arose when I was an Army military attorney (in The Judge Advocate General’s Corps) in the Panama Canal Zone in the late 1970s. I was the legal advisor to a number of infantry battalions, and one of them was a Special Forces (Green Berets) battalion. The battalion commander—Roger C. Donlon—was the first Medal of Honor winner in the Vietnam War (he is still living). Like all veterans, the number of living Medal of Honor recipients is getting smaller. For WWII, there were 464 awards, 266 of which were posthumous awards. Of the remaining 198 recipients, only two are living (ages 97 and 99). For the Korean War, there were 136 awards, 98 of which were posthumous awards. Of the remaining 38 recipients, only four are living (ages 89 to 95). There are 47 living recipients from the Vietnam War. Of the six Medal of Honor recipients from Wisconsin in the Vietnam War, four are living. One of them is Gary Wetzel who was recently interviewed (February 1, 2021) as part of the Wisconsin Veterans Story Project. You can watch it at this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l8lUK0necnM. (Neumann Companies photo) As you can see from the photo below, he rides a motorcycle and has ridden in Rolling Thunder. Gary Wetzel (Harley-Davidson Co.) Final thought John Prine was a well-known American songwriter who died at the age of 73 last year due to COVID-19. Fifty years ago, he wrote a song titled “Hello in There.” He wrote that old people “just grow lonesome” waiting for people to talk to them. The song ends: “Don’t just pass them by and stare / As if you didn’t care / Say ‘hello in there’ / Say ‘hello’.” We should take those lyrics to heart when we see our veterans. 19 Forward in Flight ~ Spring 2021