Forward in Flight - Summer 2015

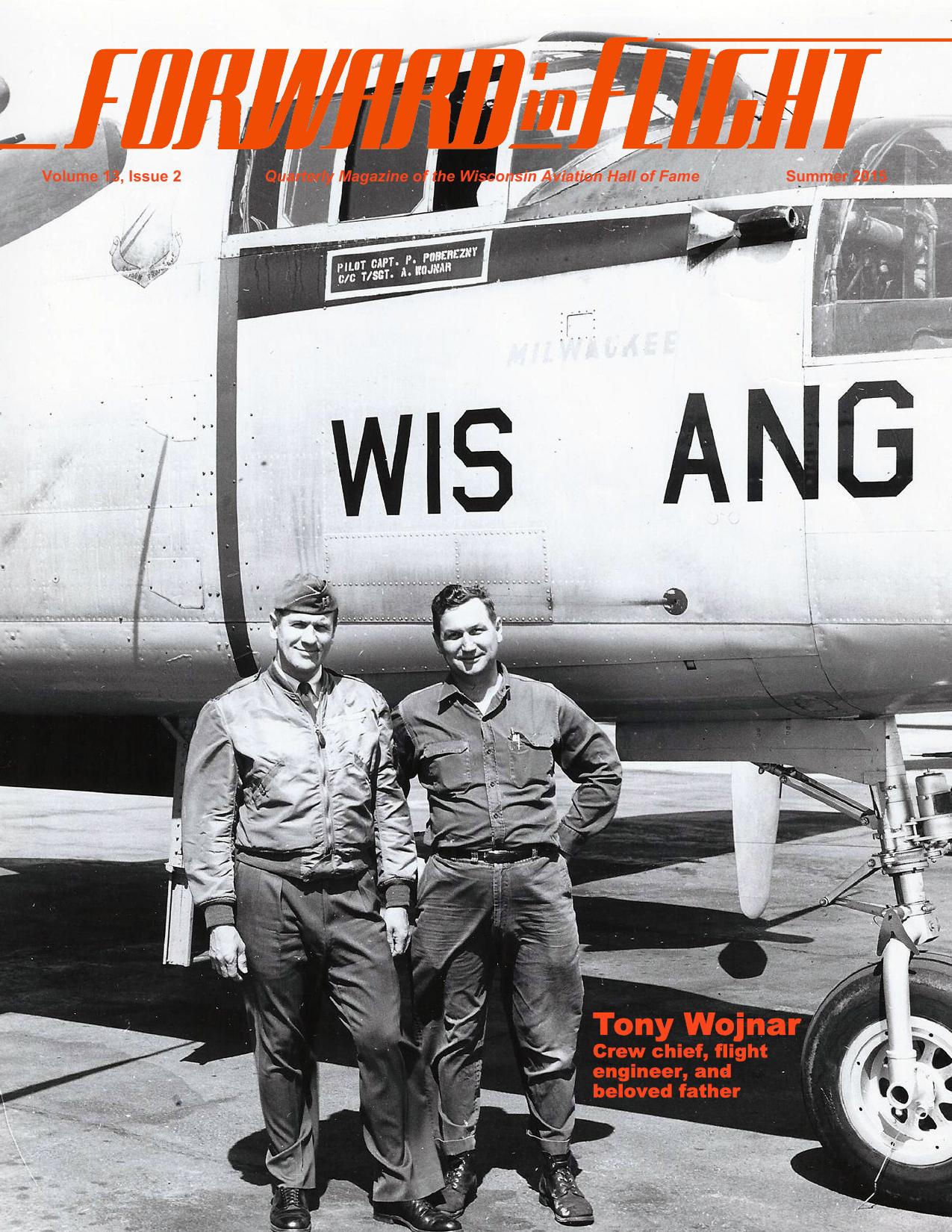

Volume 13, Issue 2 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Summer 2015 Tony Wojnar Tony Wojnar Crew chief, flight engineer, and beloved father

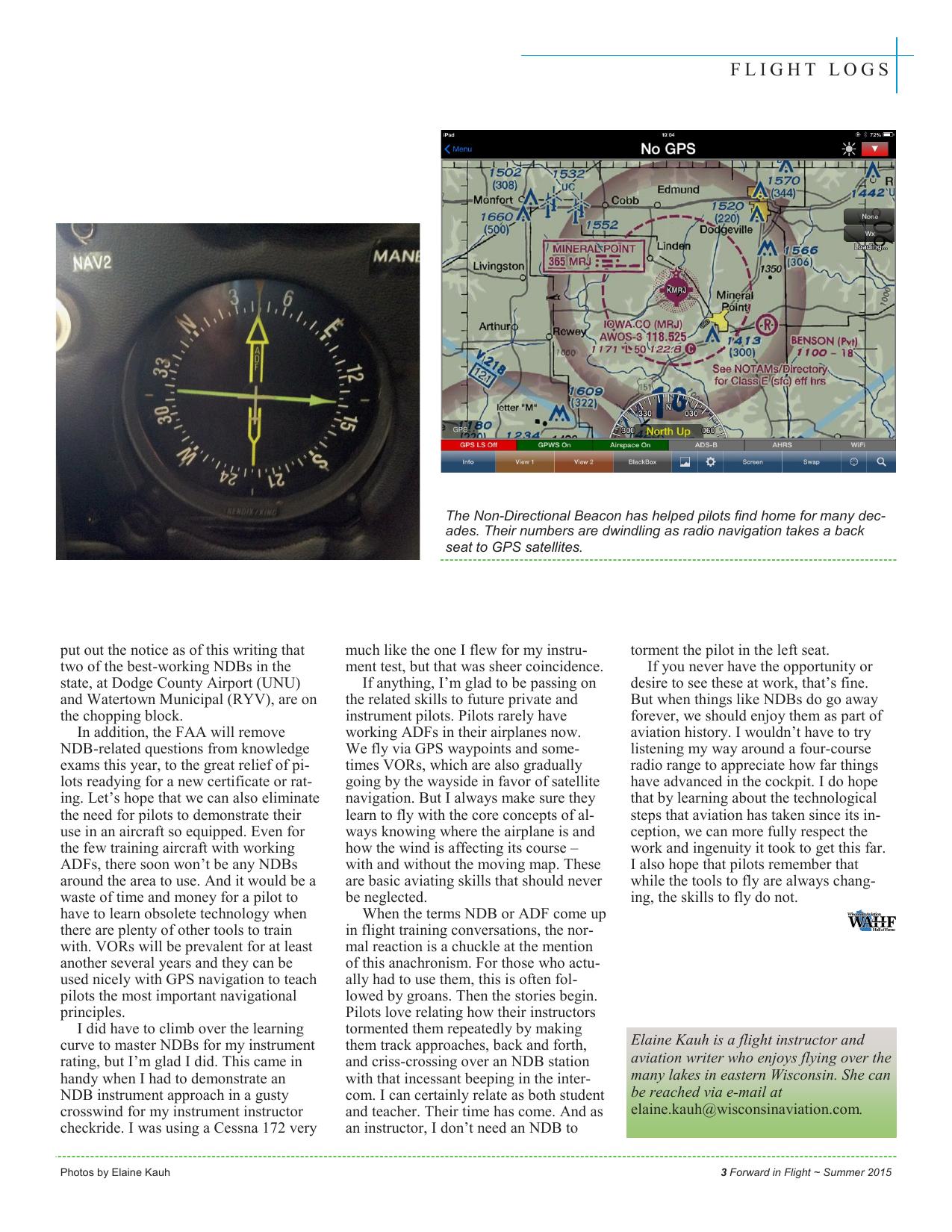

Contents Vol. 13 Issue 2/Summer 2015 FLIGHT LOGS 2 The Long Goodbye to NDBs They’re going away soon, so what’s to miss? Elaine Kauh, CFI AIR DOC 4 Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse History Aeromedical certification may be possible for some Dr. Tom Voelker, AME TALESPINS 6 Dennis “Denny” Faivre Fueled by an interest in machines, Faivre had rewarding career By Duane Esse WWII WISCONSIN 9 American Fighter Aces Honored at U.S. Capitol By Gigi Doersch WWII WISCONSIN 10 Tony Wojnar A Legacy of Leadership By Ron Wojnar WAHF enjoys communicating with members, friends, history buffs, and anyone who takes interest in our rich aviation heritage. We communicate in many ways, including Facebook, Twitter, and we even still use phone calls and face-to-face contact! Recently on Facebook, the family of George Doersch posted that George would be honored with a Congressional Gold Medal as one of our country’s Ace fighter pilots. We asked them to send a report of the ceremony, along with photos. It was an exciting day for the family, and we’re happy to share their report, and a little about George, on page 9. A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ASSOCIATION NEWS 15 70th Anniversary of the End of WWII WAHF’s 2015 Scholarship Recipients FROM THE ARCHIVES 16 Hoyt S. Vandenburg and the Mission of the US Air Force-Part 1 By Michael Goc FROM THE AIRWAYS 21 Sonex’ Monnett, Clark Lost in Plane Crash, AirVenture News, Heavy Bombers, more... GONE WEST 22 Jeremy Monnett, Mike Clark, Roy Reabe MEMBER SPOTLIGHT 24 Roger Small

President’s Message ~ by Rose Dorcey A week ago today, I heard the news that a Sonex plane had gone down at Wittman Regional Airport here in Oshkosh, and that both occupants had died. Thoughts immediately went through my mind as to who it may be. Soon I learned that it was two from Sonex Aircraft, CEO Jeremy Monnett and Mechanic Mike Clark. “No, not Mike,” I said. “Not Jeremy.” For the past eight years living in Oshkosh, I’ve met many people, a lot of them pilots. Meeting Jeremy was one of the highlights. I enjoyed his positive outlook on things, and though I didn’t know him well, it was obvious that he was an accomplished aircraft designer and visionary businessperson. More than that, he had a warm heart and a ready smile. I received an email from him several weeks ago that touched me with his kindness. Just a few words he had written, but it brightened my day, and changed the way I looked at some things. That’s what I’ll remember about him; his kindness. Mike Clark was a member of Winnebago Flying Club, the same club that my husband, John, and I are members of. Mike joined the club about a year ago. A private pilot, he was looking for an instrument instructor and chose John. Mike mastered his lessons with ease. John said early on that Mike was one of the best pilots he had ever flown with. In the year or so that Mike had been a WFC member, I can’t say that I got to know him well, but it’s easy to say that I was fond of him. Not only did we have flying in common, but we both loved motorcycling. He was a quiet, thoughtful young man. I was impressed by his determination to succeed in the aviation field, and at how much he had already accomplished, at just 20. Mike became a private pilot in minimum hours. He had recently graduated from Fox Valley Technical College’s demanding A & P program on the Dean’s List. Mike was on his way to a stellar aviation career. The morning after he died, I spoke with Mike’s father, Gary. He and Mike, and Mike’s mom, Jacky, would have been leaving on a motorcycle vacation that day. Instead, Gary was notifying family and friends of Mike’s passing. We talked about Mike’s aviation roots and goals. He stated that everything Mike had wanted in his near term goals had already come together. There was no doubt in Gary’s mind that Mike’s loftier goal of becom- Forward in Flight The only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s events. Rose Dorcey, editor 3980 Sharratt Drive Oshkosh, WI 54901-1276 Phone: 920-385-1483 920-279-6029 rdorcey@wisconsinaviationhallofame.org The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. ing a commercial pilot would be met in just a few short years. There was no doubt in my mind, either. Two young pilots have gone west. Let’s honor them when we fly, and remember them in our prayers. Inductee Trading Cards As many of you know, WAHF began producing inductee trading cards last year. It’s an effort that promotes aviation education and honors our inductees. The cards are given to youth and adults as our board members travel the state sharing our state’s aviation history. They’re also available to WAHF members for a donation that at least covers postage. We began with Richard Bong, America’s Ace of Aces, to see how popular the cards may become. Well, they’re popular alright! Of the 2,500 Richard Bong cards produced, few remain in our inventory. The cards wouldn’t be possible without the donors who sponsor them. With more than 120 men and women inducted into WAHF, many sponsorship opportunities remain. If you’re a businessperson, friend, or family member of an inductee, I ask that you please consider sponsorship of a card. The investment is $300. We’ll produce 2,500 cards, and your name will be noted on the card as its sponsor. Please contact me or one of our board members to learn more. It’s a great program to be associated with for the cards’ collectible and historical value. The cards that have been produced thus far are: 1. Richard Bong, sponsor WAHF 2. Peter Drahn, sponsor WAMA 3. James H. Flatley, Jr., sponsor Navy League 4. Ed, Ray, and James Knaup, sponsor RAPCO, Inc. 5. Don Voland, sponsor OX-5 Pioneers 6. Bill Adams, sponsor Crown Screw & Bolt, Corp. 7. Tom Hegy, sponsor Crown Screw & Bolt, Corp. 8. Paul Poberezny, sponsor Norm Poberezny 9. Ron Scott, sponsor, a friend of Ron Scott. On the cover: Milwaukee Wisconsin Air National Guard members Paul Poberezny and Crew Chief Tony Wojnar with the unit’s B-25 in 1956. Photo courtesy of Tony Wojnar.

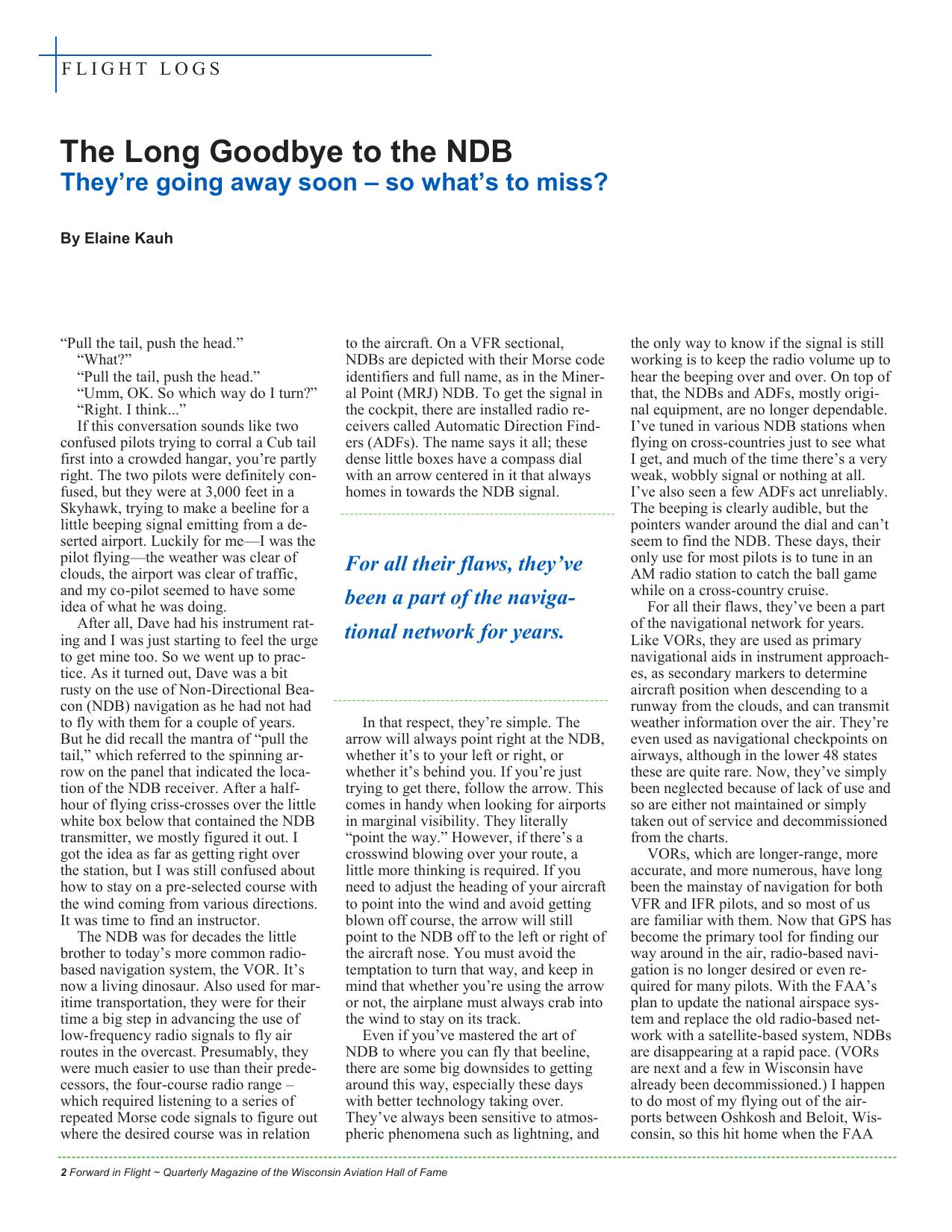

FLIGHT LOGS The Long Goodbye to the NDB They’re going away soon – so what’s to miss? By Elaine Kauh “Pull the tail, push the head.” “What?” “Pull the tail, push the head.” “Umm, OK. So which way do I turn?” “Right. I think...” If this conversation sounds like two confused pilots trying to corral a Cub tail first into a crowded hangar, you’re partly right. The two pilots were definitely confused, but they were at 3,000 feet in a Skyhawk, trying to make a beeline for a little beeping signal emitting from a deserted airport. Luckily for me—I was the pilot flying—the weather was clear of clouds, the airport was clear of traffic, and my co-pilot seemed to have some idea of what he was doing. After all, Dave had his instrument rating and I was just starting to feel the urge to get mine too. So we went up to practice. As it turned out, Dave was a bit rusty on the use of Non-Directional Beacon (NDB) navigation as he had not had to fly with them for a couple of years. But he did recall the mantra of “pull the tail,” which referred to the spinning arrow on the panel that indicated the location of the NDB receiver. After a halfhour of flying criss-crosses over the little white box below that contained the NDB transmitter, we mostly figured it out. I got the idea as far as getting right over the station, but I was still confused about how to stay on a pre-selected course with the wind coming from various directions. It was time to find an instructor. The NDB was for decades the little brother to today’s more common radiobased navigation system, the VOR. It’s now a living dinosaur. Also used for maritime transportation, they were for their time a big step in advancing the use of low-frequency radio signals to fly air routes in the overcast. Presumably, they were much easier to use than their predecessors, the four-course radio range – which required listening to a series of repeated Morse code signals to figure out where the desired course was in relation to the aircraft. On a VFR sectional, NDBs are depicted with their Morse code identifiers and full name, as in the Mineral Point (MRJ) NDB. To get the signal in the cockpit, there are installed radio receivers called Automatic Direction Finders (ADFs). The name says it all; these dense little boxes have a compass dial with an arrow centered in it that always homes in towards the NDB signal. For all their flaws, they’ve been a part of the naviga- tional network for years. In that respect, they’re simple. The arrow will always point right at the NDB, whether it’s to your left or right, or whether it’s behind you. If you’re just trying to get there, follow the arrow. This comes in handy when looking for airports in marginal visibility. They literally “point the way.” However, if there’s a crosswind blowing over your route, a little more thinking is required. If you need to adjust the heading of your aircraft to point into the wind and avoid getting blown off course, the arrow will still point to the NDB off to the left or right of the aircraft nose. You must avoid the temptation to turn that way, and keep in mind that whether you’re using the arrow or not, the airplane must always crab into the wind to stay on its track. Even if you’ve mastered the art of NDB to where you can fly that beeline, there are some big downsides to getting around this way, especially these days with better technology taking over. They’ve always been sensitive to atmospheric phenomena such as lightning, and 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame the only way to know if the signal is still working is to keep the radio volume up to hear the beeping over and over. On top of that, the NDBs and ADFs, mostly original equipment, are no longer dependable. I’ve tuned in various NDB stations when flying on cross-countries just to see what I get, and much of the time there’s a very weak, wobbly signal or nothing at all. I’ve also seen a few ADFs act unreliably. The beeping is clearly audible, but the pointers wander around the dial and can’t seem to find the NDB. These days, their only use for most pilots is to tune in an AM radio station to catch the ball game while on a cross-country cruise. For all their flaws, they’ve been a part of the navigational network for years. Like VORs, they are used as primary navigational aids in instrument approaches, as secondary markers to determine aircraft position when descending to a runway from the clouds, and can transmit weather information over the air. They’re even used as navigational checkpoints on airways, although in the lower 48 states these are quite rare. Now, they’ve simply been neglected because of lack of use and so are either not maintained or simply taken out of service and decommissioned from the charts. VORs, which are longer-range, more accurate, and more numerous, have long been the mainstay of navigation for both VFR and IFR pilots, and so most of us are familiar with them. Now that GPS has become the primary tool for finding our way around in the air, radio-based navigation is no longer desired or even required for many pilots. With the FAA’s plan to update the national airspace system and replace the old radio-based network with a satellite-based system, NDBs are disappearing at a rapid pace. (VORs are next and a few in Wisconsin have already been decommissioned.) I happen to do most of my flying out of the airports between Oshkosh and Beloit, Wisconsin, so this hit home when the FAA

FLIGHT LOGS The Non-Directional Beacon has helped pilots find home for many decades. Their numbers are dwindling as radio navigation takes a back seat to GPS satellites. put out the notice as of this writing that two of the best-working NDBs in the state, at Dodge County Airport (UNU) and Watertown Municipal (RYV), are on the chopping block. In addition, the FAA will remove NDB-related questions from knowledge exams this year, to the great relief of pilots readying for a new certificate or rating. Let’s hope that we can also eliminate the need for pilots to demonstrate their use in an aircraft so equipped. Even for the few training aircraft with working ADFs, there soon won’t be any NDBs around the area to use. And it would be a waste of time and money for a pilot to have to learn obsolete technology when there are plenty of other tools to train with. VORs will be prevalent for at least another several years and they can be used nicely with GPS navigation to teach pilots the most important navigational principles. I did have to climb over the learning curve to master NDBs for my instrument rating, but I’m glad I did. This came in handy when I had to demonstrate an NDB instrument approach in a gusty crosswind for my instrument instructor checkride. I was using a Cessna 172 very Photos by Elaine Kauh much like the one I flew for my instrument test, but that was sheer coincidence. If anything, I’m glad to be passing on the related skills to future private and instrument pilots. Pilots rarely have working ADFs in their airplanes now. We fly via GPS waypoints and sometimes VORs, which are also gradually going by the wayside in favor of satellite navigation. But I always make sure they learn to fly with the core concepts of always knowing where the airplane is and how the wind is affecting its course – with and without the moving map. These are basic aviating skills that should never be neglected. When the terms NDB or ADF come up in flight training conversations, the normal reaction is a chuckle at the mention of this anachronism. For those who actually had to use them, this is often followed by groans. Then the stories begin. Pilots love relating how their instructors tormented them repeatedly by making them track approaches, back and forth, and criss-crossing over an NDB station with that incessant beeping in the intercom. I can certainly relate as both student and teacher. Their time has come. And as an instructor, I don’t need an NDB to torment the pilot in the left seat. If you never have the opportunity or desire to see these at work, that’s fine. But when things like NDBs do go away forever, we should enjoy them as part of aviation history. I wouldn’t have to try listening my way around a four-course radio range to appreciate how far things have advanced in the cockpit. I do hope that by learning about the technological steps that aviation has taken since its inception, we can more fully respect the work and ingenuity it took to get this far. I also hope that pilots remember that while the tools to fly are always changing, the skills to fly do not. Elaine Kauh is a flight instructor and aviation writer who enjoys flying over the many lakes in eastern Wisconsin. She can be reached via e-mail at elaine.kauh@wisconsinaviation.com. 3 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

AIR DOC Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse History Aeromedical certification may be possible for some Dr. Tom Voelker, AME Voelkerta@yahoo.com Hello, Airmen! I’m loving the weather, and I would guess you are too. Welcome to spring! Baseball (another of my passions) is starting in Wisconsin Rapids this week. And I don’t need to freeze during pre-flights! What more could a guy want? Well, it’s not all rosy. This morning I was to fly my daughter to Mitchell International Airport (MKE) in Milwaukee so she could take a commercial flight to Florida. We needed to get to MKE by 6:00 a.m., so I thought flying was the best way to get her there. I guessed wrong. Fortunately I was able to figure that out before we went to bed last night, so we could get up nice and early for the three-hour drive. Heavy rain, fog, and low ceilings were the order of the morning, so I’m glad we drove. Checking the METARs after I got home revealed that I “probably” would have gotten into MKE, but I would not have been able to land back home in Wisconsin Rapids. “Probably” is not a word I like to use when flying! “Probably” does apply to aeromedical certification, though. I’m referring to the likelihood of an applicant for a flight physical successfully obtaining their Medical Certificate. Very highly probable is a more apt description, as more than 99.5% of all FAA medical certification applications result in issuance. Some of these applications require review of records and further testing, such as in diabetics or airmen with heart disease, as we have discussed previously. It is rare that an airman is ultimately denied, however. That is why I took notice in the past six months when I saw an inordinate number of deferrals and denials cross my desk. Most of these deferrals and all of the denials involved one area of medicine, and this is what I want to discuss in this issue. The subject of this column is certification of airmen with a history of mental disease or substance abuse. It seems to me that some people, especially new Stu- dent Pilot applicants, are taking the issue of drug and alcohol use less seriously than I have seen in the past. I don’t know if this is a result of society’s more permissive attitude, as evidenced by the legalization of marijuana in some states, but I have detected a change. My purpose in this column is to ensure that you are aware of the facts and issues when it comes to certification with this particular medical history. First I would like to tackle the problem of aeromedical certification in the presence of clinical depression. There is an inherent conflict with depression in aeromedical circles. We certainly want our pilots to be healthy, and we certainly don’t want severely depressed, even suicidal pilots, flying. This was tragically demonstrated recently when a depressed German copilot locked the pilot out of the cockpit and intentionally crashed his jet in the Alps, killing all aboard. I also recall a solo pilot intentionally crashing his Cirrus on the runway of an airport in the Dakotas, taking his life in the process. The FAA has traditionally denied applications of airman who were being treated for depression with medication. Essentially all of the antidepressant medication is “centrally acting,” that is, it works on the brain. OKC has a blanket policy of disallowing any medications with this property, and the medications are likely to have side effects that would cloud an airman’s judgment or make them sleepy. This “blanket denial” had led, over the years, to a significant underreporting of depression by airmen. If they didn’t tell us they had depression we would have no reason to deny their certification. While falsification of the flight physical application (the oft-mentioned 8500-8 which is now filled out by the MedXpress online program) is strictly forbidden, frowned upon, and frankly illegal, the FAA can’t enforce what they don’t know about. I have often stressed that what keeps the skies safe, from an 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame aeromedical standpoint, is the honest self -reporting by airmen about their medical conditions. In recent years new antidepressant medications have been developed that have very few side-effects. Many people now have essentially cured their depression with medications that do not cause any problems. About five or six years ago (or maybe more – time seems to fly!) the Aeromedical Certification folks at OKC started a program that allows an airman with depression to fly while on medication. This process, called HIMS (Human Intervention Motivation Study) is primarily designed for commercial pilots. It involves the airlines working with the pilots, their unions, and the FAA to safely get the pilot treated with medications while monitoring for side effects. This process has worked very well for the airline industry. The HIMS program is available to non commercial pilots as well. The program takes a few months to complete, but if an airman with depression really wants to fly, there is a way. You can discuss this with an AME, or you can call the FAA directly and discuss it with them. I would suggest calling the Great Lakes Regional Flight Surgeon’s office if you are interested in this program. They can point you in the right direction. A different problem is what is commonly called “manic-depression,” more properly called Bipolar Disorder. I had one airman applicant recently who claimed this history. In addition, he was on a medication for this condition that was clearly not safe for flight. While this airman was not denied his certification, his application was deferred and more information was requested, including a psychiatric evaluation by a psychiatrist who is specifically knowledgeable of aviation medicine. Usually that means a psychiatrist in the HIMS program. Yet another case I had recently involved an applicant with a history of “personality disorder.” There are various-

AIR DOC ly types of these disorders, but they are all on the list of “disqualifying conditions” according to the FAA. Treatment can be very difficult, and often the condition cannot be adequately treated, as the underlying problem is one of the person’s personality, something that we frequently cannot change. Again, this patient was referred to a psychiatrist for further evaluation, and if the diagnosis is correct, I doubt the medical certificate will be issued. One final psychiatric condition causing aeromedical certification problems that I have run across is ADHD or “attention deficit disorder.” This is a condition that used to be thought to be confined to childhood, but it is increasingly being seen into adulthood. The medications used for this condition are absolutely disqualifying for flight certification. I have had only one airman (an applicant for ATC training) successfully receive his medical with this diagnosis. That is because after further psychiatric evaluation he was found not to have the condition at all. Too frequently in the past children were diagnosed with ADHD (or “hyperactivity”) just to get them on medication and controlled. In my opinion, all patients, especially all children, who are being evaluated for ADHD need to have an in-depth evaluation by a specialist in that area. Finally, I want to touch on alcohol and other drug abuse. As I mentioned earlier, more airmen are properly (and honestly) reporting on their 8500-8 forms that they have had convictions for alcohol or drug related offenses (such as DUI), or have had problems with alcohol or drug use in the past. This is a huge “red flag” for the FAA. Two or more DUIs, or one DUI with a blood alcohol level of 0.015 or higher, or any other drug or alcohol-related offense, will almost certainly result in a deferral for further evaluation. This evaluation might be a formal one, such as with the Student Pilot applicant I had recently who didn’t think his one DUI and two marijuana convictions were a big deal. It may not be too important if you live in Colorado and have no desire to fly, but the FAA takes it very seriously. Sometimes the evaluation is less rigorous, but it will always involve review of the arrest records for any DUI or other action which involved drugs or alcohol. I had a recent applicant with a history of multiple DUIs. He noted trouble getting his arrest records and could not supply them to the FAA. When OKC pressed him he was able to come up with the reports. They did show the reported incidents, as well as mention of several other alcohol and drug-related of- fenses. It’s no wonder he was denied! I should also note that the HIMS program also works with pilots with issues of drug and alcohol dependence. After comprehensive treatment and with very close follow-up it is indeed possible for an alcoholic or drug addict to regain his or her medical! So what is the common link in all of these cases? The best action for the airman applicant would be to discuss their situation with an AME or with the FAA (and I think the Regional Flight Surgeon’s office would be best). As I had mentioned a few months ago, this conversation can be confidential (such as “I have this friend who wants to fly but he has the following history...”). This conversation should take place before the flight physical visit. That way the airman can at least get all records in order prior to the examination. And if it really looks like certification is not in the cards for that particular person, at least they can find out before spending a lot of money, not only on the physical, but on initial flight training as well. Flight instructors can take heed of this advice as well. I advise the CFIs who I work with to feel free to call me about certification issues, or to have the airmen call themselves. I think, with the recent number of cases of alcohol and drug issues that I am seeing, that the CFI addressing that issue specifically makes sense as well. If nothing else, it would underscore the seriousness we place on the alcohol regulations. I hope this was helpful, or at the least, educational. Now, I know tomorrow’s weather is going to be great. Get out and fly (but safely!) —Alpha Mike 2031 Peach Street Wisconsin Rapids, WI 54494 “Alpha Mike” is Dr. Tom Voelker, AME, a family practitioner in Wisconsin Rapids. He and his wife, Kathy, are the parents of four daughters. Tom flies N6224P, a Comanche 250, out of Alexander Field, South Wood County Airport (ISW). 5 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

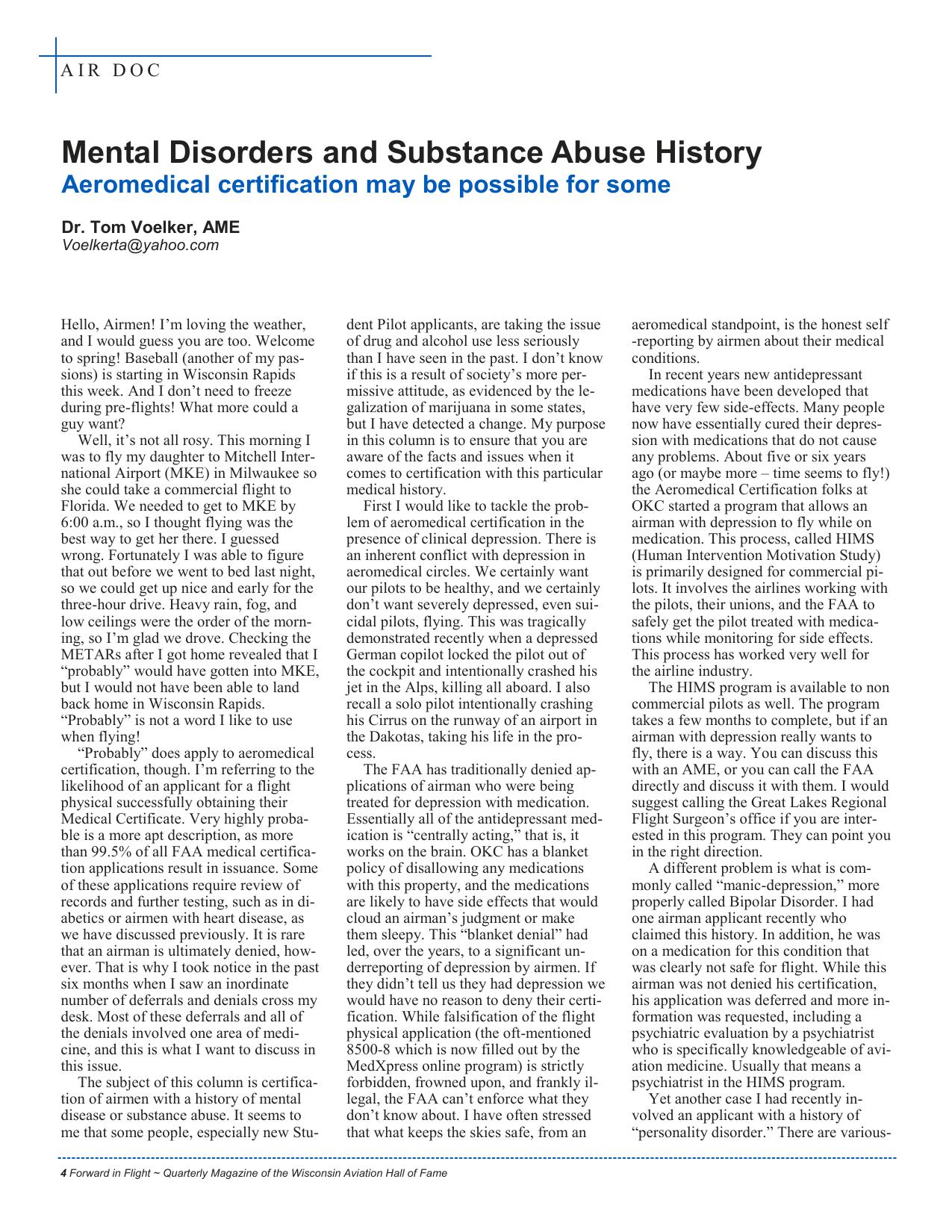

IN THE PATTERN Dennis “Denny” Faivre Fueled by an interest in machines, Faivre had rewarding careers By Duane Esse, with the assistance of Dan Knutson and Jayne Simpson “Mom and Dad, can I go over to Paul’s house and watch him work?” That was 7-year-old Dennis “Denny” Faivre wanting to watch his neighbor, Paul Cowing , fix machines. Fortunately, Paul was not annoyed by Denny’s curiosity, and he frequently stopped working to discuss or show Denny what he was doing. After many months of shadowing and learning from Paul, Denny ventured into business by starting a lawnmower repair shop. He was 9 years old. “As long as I can remember, I have been interested in tools and machines,” Denny said. Denny was born in Baraboo, Wisconsin, on March 17, 1945. His family moved to a farm near North Freedom a few years later where he attended North Freedom Grade School and Baraboo High School. Denny then enrolled in a two-year automobile mechanic course at Madison Area Technical College (MATC) and graduated in June 1965. His favorite instructor at MATC was Harry Beach, who had stated numerous times that Denny was the best student he had ever taught. In 1994, after not seeing one another since Denny graduated, they reconnected. They got together numerous times. The mutual admiration was evident as they shared stories of the days in the auto mechanic classes. Those meetings ended when Harry passed away in 2012, at the age of 101. Before graduating from MATC, Denny was working part-time at the Chevrolet garage in Waunakee. He was considering staying there as a fulltime mechanic when Harry told him, “You are going to work at Kayser Ford in Madison.” Harry knew there would be a better chance to advance in the business at Kayser, and 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame there was. Denny was draft eligible and holding off from entering the military when the draft notice arrived. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and was assigned to Fort Knox, Kentucky, for basic training. In March 1966, he was assigned to Fort Eustis, Virginia, for an 11-week Huey Helicopter Mechanic School. He was one of the top 10 students in the class and was assigned to an 8-week Chinook Helicopter Mechanic School. “The Huey school was simple compared to the Chinook training,” Denny recalls. “The Huey had tubes and bell cranks for control while the Chinook had electrically controlled hydraulic-operated controls.” Denny said it was the beginning of computer use for controlling systems. The complexity was reflected in the price of the two; the Huey cost about

$250,000 while the Chinook cost about $1.5 million. Denny’s next assignment was at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he would become part of a newly formed company, the 196th Aviation Company. The company was being formed to operate in Viet Nam. They were transported to Stockton, California, which had been a WWII training base, and where Denny said the food was to die for! The company spent 3 weeks staging and loading on an aircraft carrier, the USS Connitor, which had just been pulled out of mothballs. It was in disrepair, having holes in the flight deck, and lost power once they were at sea. There was a Chinese chef on the ship who provided outstanding food. Denny gained 30 pounds on the 3-week trip to Viet Nam. He lost the 30 pounds in the first month in Viet Nam. The company arrived in Viet Nam in January 1967. Their first assignment was to construct barracks while they lived in tents. “It was an introduction to living in Viet Nam with heat, humidity, bugs, and snakes,” Denny said. He was assigned as a flight engineer on a Chinook helicopter. At 22 years old, he was responsible for maintenance of a complex $1.5 million helicopter, operating in brutal weather, Photos courtesy of Dennis Faivre and in an environment where people were trying to kill him. The Chinook has two Pratt and Whitney gas turbine engines producing 10,500 total horsepower. It carries 650 gallons of fuel and burns 300 gallons of fuel per hour. With a high-density altitude and quite often being operated over gross weight, the Chinook did not perform well. Missions varied and covered a large area. One day they carried troops to a jungle-landing zone and other times supplies and equipment were carried. Whenever they would be on the ground for a few minutes, Denny would inspect the Chinook and perform maintenance as required. Spare parts were carried on the Chinook for repairs in the field. “The heat and humidity took a toll on everything, from human health, to the helicopter, to boots and clothing,” he said. “It would not be uncommon to drop troops with new boots and fatigues at a jungle landing zone to be picked up 3 weeks later with clothing and boots rotting away.” The Chinook was on a 25-hour maintenance schedule. When it was in for an inspection, Denny would fly with another crew that needed a flight engineer. “We volunteered for flight duty and the Previous page: Denny Faivre (left) with his good friend and mentor, Harry “Shorty” Beach. Above: Denny in his early years as an aviation mechanic. only way to get off would be for medical issues,” he said. Denny worked 90 days in one stretch without a day off. “I flew an average of over 6 hours per day for 10 months,” Denny explained. “The longest day was 12 hours and 45 minutes.” There was never a dull moment in the year Denny served in Viet Nam. On one mission, they had to evacuate women and children from a village before troops were sent in to search for the enemy. “It was almost like sending the enemy a telegram to warn them they would be back looking for them,” Denny said. “We departed with 125 women and children, the most people we ever carried, and landed with 126. A woman gave birth on the flight.” Since most missions were flown at low altitude, there was always a danger of having an engine damaged by enemy fire or ingesting dust or debris on takeoff and landing. “I was involved in 12 emergency landings and most were a result of part 7 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

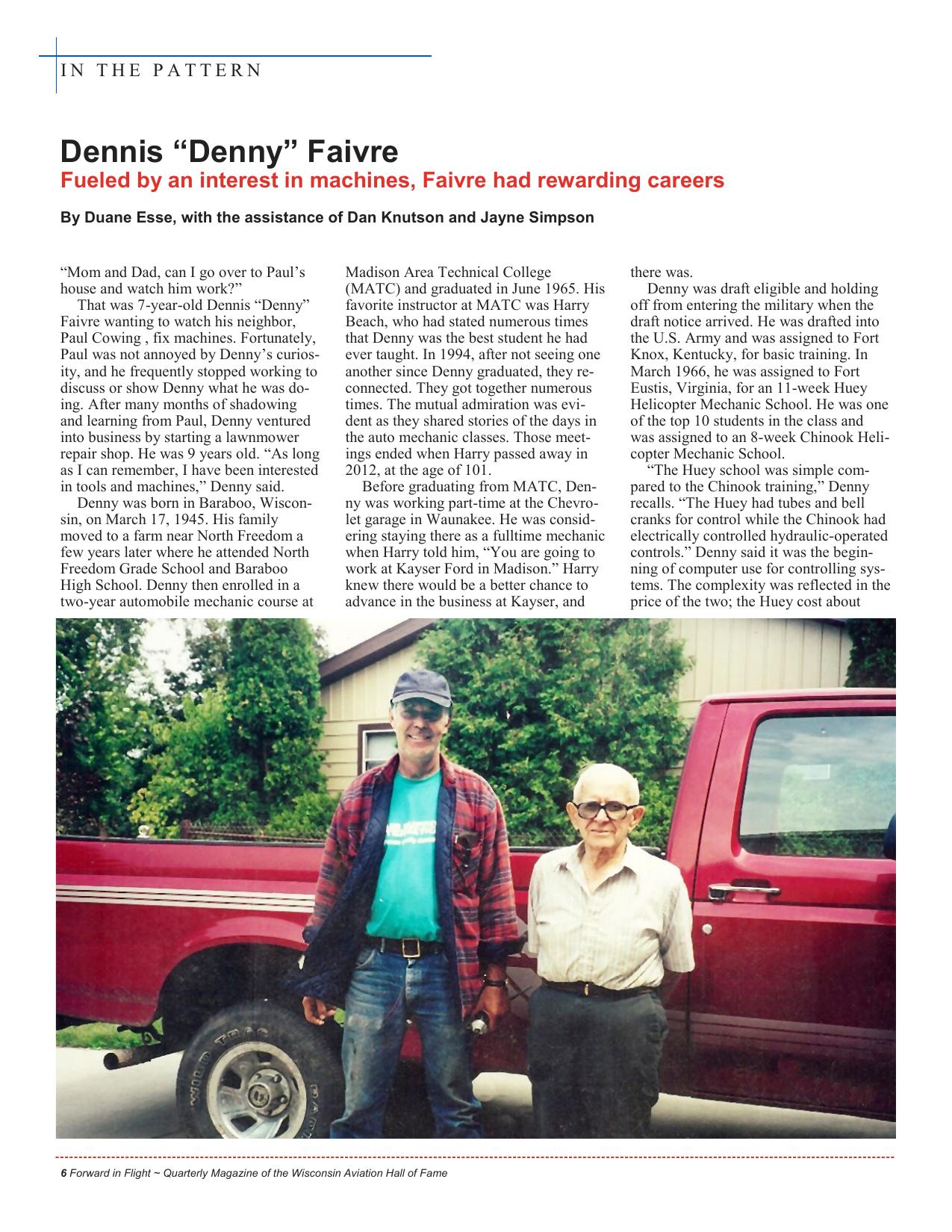

IN THE PATTERN failure,” Denny said. Of the 12, they were shot down twice. They made two auto rotations into jungle landing zones due to enemy gunfire. “On one of the 12 emergency landings, we were transporting 8,000 pounds of explosives in the fuselage when we lost power on one engine and landed through trees,” Denny said. “Luckily we survived.” The company established a regulation after the event, which forbade carrying explosives internally. Explosives had to be carried in a sling that could quickly be jettisoned by the crew chief in an emergency. Denny left Viet Nam in January 1968. He flew to Japan and then Seattle where he was mustered out of the Army. He had been in Viet Nam for 12 months and said, “I did not want to go, I did not leave anything there, and I have no desire to go back,” Denny said. In the year he was there, he was promoted to E-5 and was doing the work assigned to an E-6. He flew more than 1,850 hours in the Chinook during his tour. Upon discharge, Denny went back to Kayser Ford in Madison as an auto mechanic. Living in North Freedom, with an hour drive to Kayser, and the cost of fuel being factors, he took an auto mechanic job at Baraboo Ford. In 1969, he enrolled in the Aviation Mechanic program at Blackhawk Technical College in Janesville. He graduated from the 11-month program in April 1970. In March 1974, Denny started Faivre Aviation, offering aircraft maintenance, at the Sauk-Prairie Airport (91C). He operated out of a chicken coop, as he said, and in the mid-1980s bought a large hangar at the Sauk-Prairie Airport. He gradually built the business in which he serviced customers from Mauston, New Lisbon, Madison, Boscobel, and Wonewoc, to name a few. “I was in business in Sauk for 28 years and most days I could not wait to get to work,” Denny said. After numerous attempts to stop the fuel flow, using buckets to catch the fuel, Denny was called at home. He said he would be there with a new sump drain in half an hour. He arrived, replaced the drain, and had the crew in the air quickly. He went above and beyond to accommodate the problems pilots had with their airplanes. One day a flight instructor was giving a flight review at the Sauk-Prairie Airport. When the pilot attempted to drain the wing sumps, one would not shut off. After numerous attempts to stop the fuel flow, using buckets to catch the fuel, Denny was called at home. He said he would be 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame After an engine overhaul, Denny watched and listened during the engine’s run-up. there with a new sump drain in half an hour. He arrived, replaced the drain, and had the crew in the air quickly. This was on a Sunday afternoon. It was not uncommon for Denny to be available on short notice—nights and weekends—to accommodate pilots with mechanical problems. Today, he continues to perform aviation maintenance and annuals on a limited basis. After doing some major remodeling on their home, starting in 1976, Denny began to take on projects for interior remodeling of older homes and for newly constructed homes. He concentrated on cabinets, flooring, and paneling. He bought all the necessary tooling and machines for those projects and today has a complete woodworking factory. He owns 120 acres, mostly in the forest, and can harvest trees, saw logs into lumber, dry boards in a kiln he constructed, and build them into a beautiful piece with the finish requested by the customer. Since Denny started the woodworking business in 1998, he has not advertised once. He is usually booked with projects three or more months in advance. Denny said that his 45 years of aviation maintenance and woodworking has been fun. That has been evident in the quality of work he has accomplished during those years. He has made a lot of friends by being honest, reliable, trustworthy, and professional in all his business ventures. Denny turned 70 in March. He recently said that he is going to slow down and do some things he has put aside over the years. That may eventually come to pass, but those who know him will agree the quality of his work will not suffer. Going back to that 9-year-old who started a lawnmower business to the present, Denny has built a legacy established in three areas: his expertise, caring for people, and helping with their problems. Friends cannot see him becoming completely idle and sitting in a rocking chair drinking green tea. He will probably always respond to requests for his expertise, but he may be able to slow down to his desired pace. After all, it is a much deserved “retirement.” Photo courtesy of Dennis Faivre

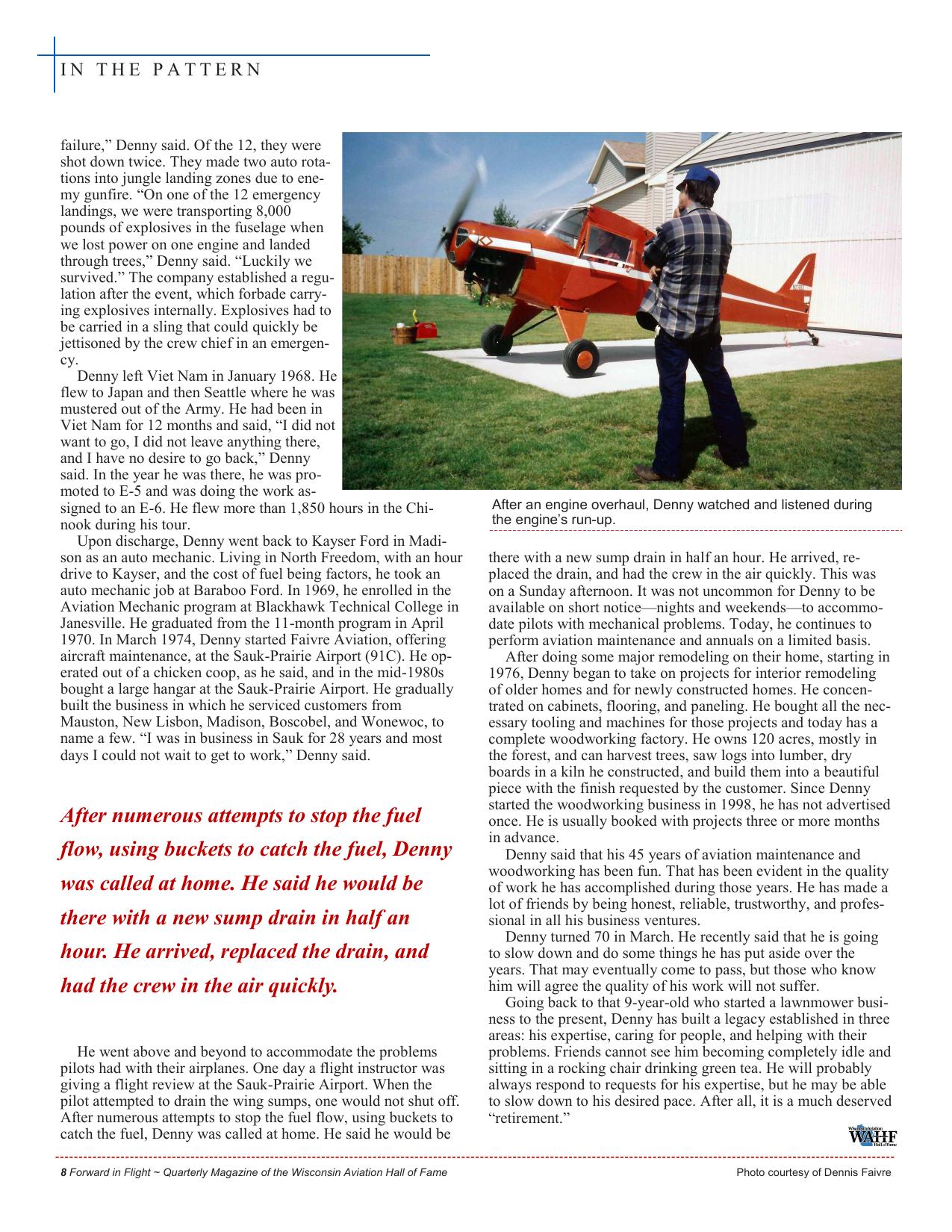

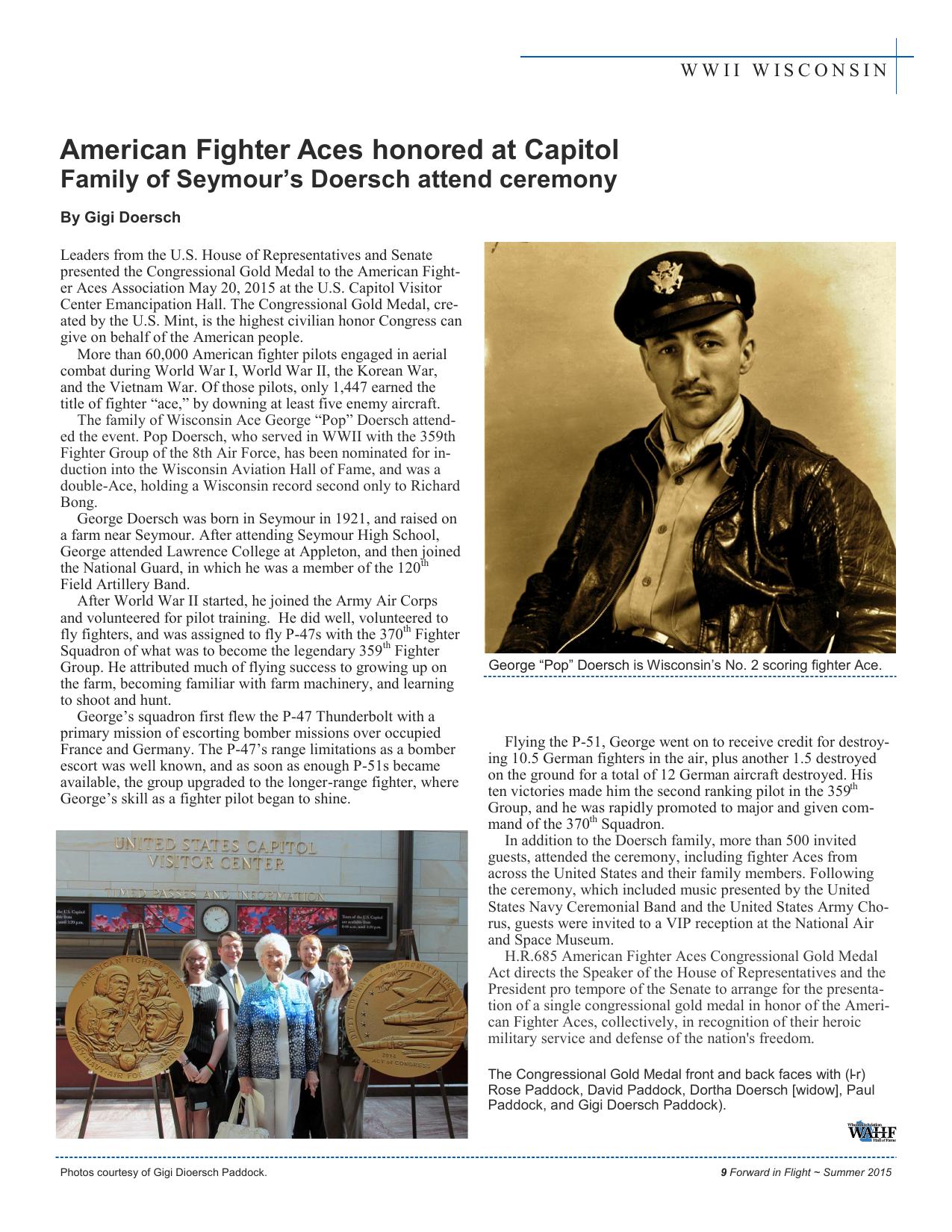

WWII WISCONSIN American Fighter Aces honored at Capitol Family of Seymour’s Doersch attend ceremony By Gigi Doersch Leaders from the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate presented the Congressional Gold Medal to the American Fighter Aces Association May 20, 2015 at the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center Emancipation Hall. The Congressional Gold Medal, created by the U.S. Mint, is the highest civilian honor Congress can give on behalf of the American people. More than 60,000 American fighter pilots engaged in aerial combat during World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Of those pilots, only 1,447 earned the title of fighter “ace,” by downing at least five enemy aircraft. The family of Wisconsin Ace George “Pop” Doersch attended the event. Pop Doersch, who served in WWII with the 359th Fighter Group of the 8th Air Force, has been nominated for induction into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame, and was a double-Ace, holding a Wisconsin record second only to Richard Bong. George Doersch was born in Seymour in 1921, and raised on a farm near Seymour. After attending Seymour High School, George attended Lawrence College at Appleton, and then joined the National Guard, in which he was a member of the 120th Field Artillery Band. After World War II started, he joined the Army Air Corps and volunteered for pilot training. He did well, volunteered to fly fighters, and was assigned to fly P-47s with the 370th Fighter Squadron of what was to become the legendary 359th Fighter Group. He attributed much of flying success to growing up on the farm, becoming familiar with farm machinery, and learning to shoot and hunt. George’s squadron first flew the P-47 Thunderbolt with a primary mission of escorting bomber missions over occupied France and Germany. The P-47’s range limitations as a bomber escort was well known, and as soon as enough P-51s became available, the group upgraded to the longer-range fighter, where George’s skill as a fighter pilot began to shine. George “Pop” Doersch is Wisconsin’s No. 2 scoring fighter Ace. Flying the P-51, George went on to receive credit for destroying 10.5 German fighters in the air, plus another 1.5 destroyed on the ground for a total of 12 German aircraft destroyed. His ten victories made him the second ranking pilot in the 359th Group, and he was rapidly promoted to major and given command of the 370th Squadron. In addition to the Doersch family, more than 500 invited guests, attended the ceremony, including fighter Aces from across the United States and their family members. Following the ceremony, which included music presented by the United States Navy Ceremonial Band and the United States Army Chorus, guests were invited to a VIP reception at the National Air and Space Museum. H.R.685 American Fighter Aces Congressional Gold Medal Act directs the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President pro tempore of the Senate to arrange for the presentation of a single congressional gold medal in honor of the American Fighter Aces, collectively, in recognition of their heroic military service and defense of the nation's freedom. The Congressional Gold Medal front and back faces with (l-r) Rose Paddock, David Paddock, Dortha Doersch [widow], Paul Paddock, and Gigi Doersch Paddock). Photos courtesy of Gigi Dioersch Paddock. 9 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

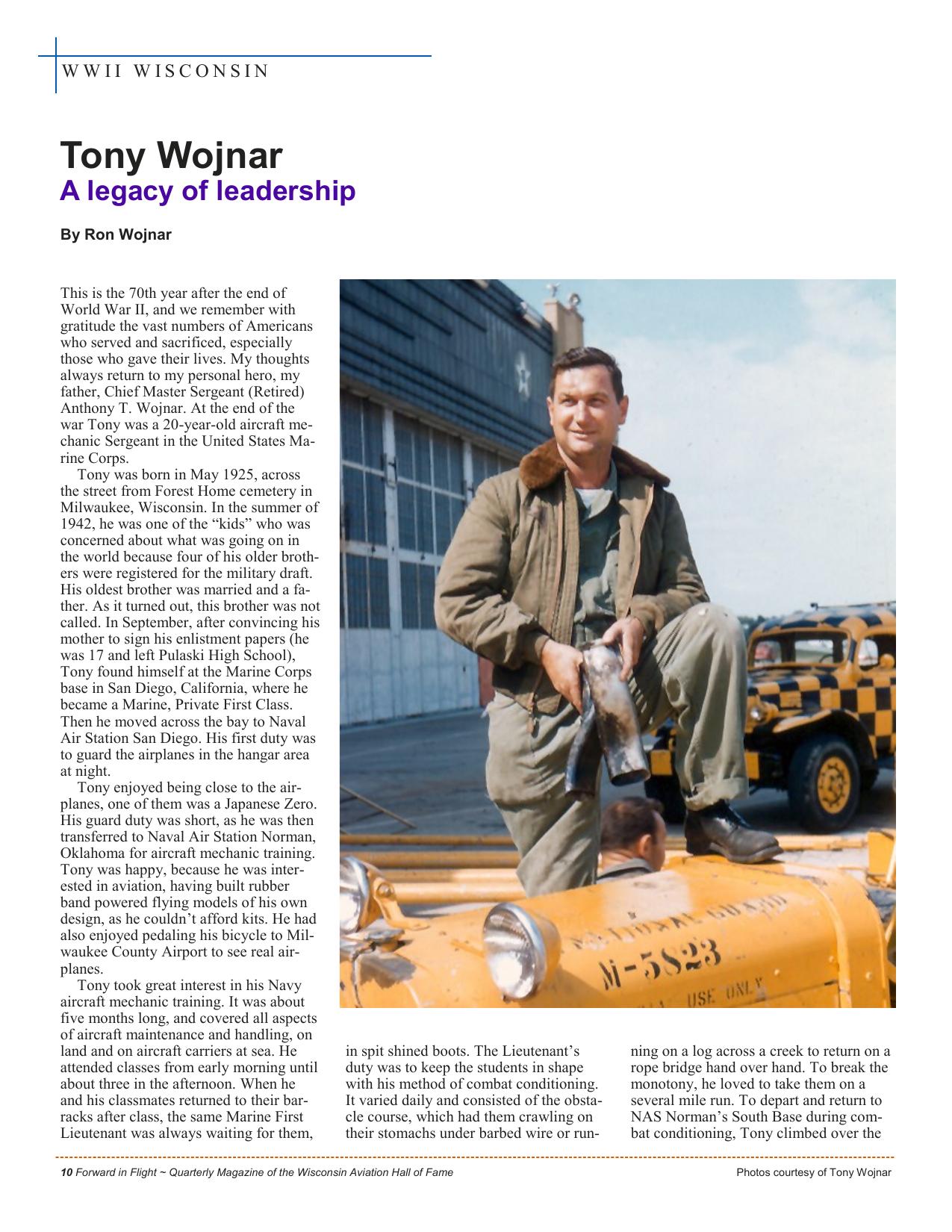

WWII WISCONSIN Tony Wojnar A legacy of leadership By Ron Wojnar This is the 70th year after the end of World War II, and we remember with gratitude the vast numbers of Americans who served and sacrificed, especially those who gave their lives. My thoughts always return to my personal hero, my father, Chief Master Sergeant (Retired) Anthony T. Wojnar. At the end of the war Tony was a 20-year-old aircraft mechanic Sergeant in the United States Marine Corps. Tony was born in May 1925, across the street from Forest Home cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In the summer of 1942, he was one of the “kids” who was concerned about what was going on in the world because four of his older brothers were registered for the military draft. His oldest brother was married and a father. As it turned out, this brother was not called. In September, after convincing his mother to sign his enlistment papers (he was 17 and left Pulaski High School), Tony found himself at the Marine Corps base in San Diego, California, where he became a Marine, Private First Class. Then he moved across the bay to Naval Air Station San Diego. His first duty was to guard the airplanes in the hangar area at night. Tony enjoyed being close to the airplanes, one of them was a Japanese Zero. His guard duty was short, as he was then transferred to Naval Air Station Norman, Oklahoma for aircraft mechanic training. Tony was happy, because he was interested in aviation, having built rubber band powered flying models of his own design, as he couldn’t afford kits. He had also enjoyed pedaling his bicycle to Milwaukee County Airport to see real airplanes. Tony took great interest in his Navy aircraft mechanic training. It was about five months long, and covered all aspects of aircraft maintenance and handling, on land and on aircraft carriers at sea. He attended classes from early morning until about three in the afternoon. When he and his classmates returned to their barracks after class, the same Marine First Lieutenant was always waiting for them, in spit shined boots. The Lieutenant’s duty was to keep the students in shape with his method of combat conditioning. It varied daily and consisted of the obstacle course, which had them crawling on their stomachs under barbed wire or run- 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ning on a log across a creek to return on a rope bridge hand over hand. To break the monotony, he loved to take them on a several mile run. To depart and return to NAS Norman’s South Base during combat conditioning, Tony climbed over the Photos courtesy of Tony Wojnar

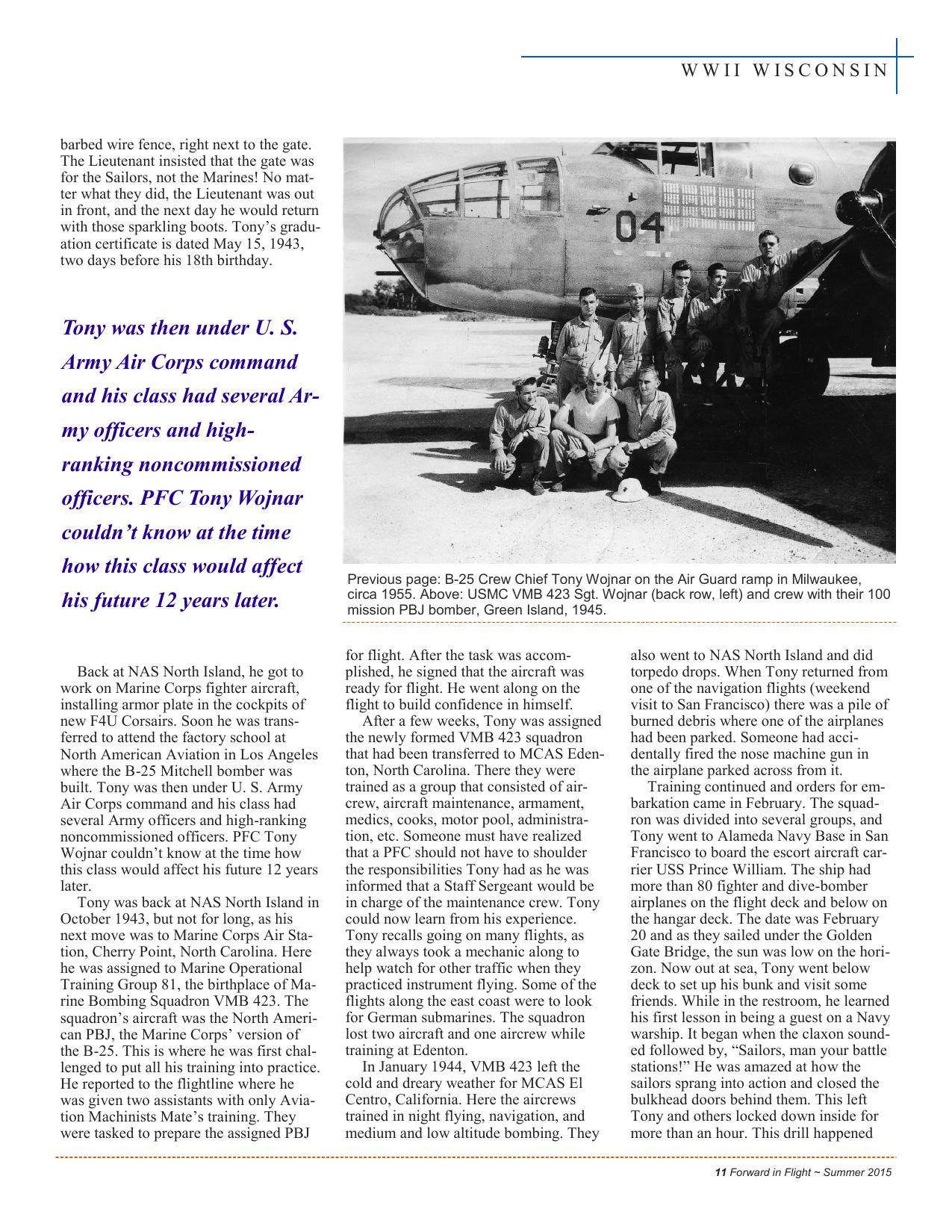

WWII WISCONSIN barbed wire fence, right next to the gate. The Lieutenant insisted that the gate was for the Sailors, not the Marines! No matter what they did, the Lieutenant was out in front, and the next day he would return with those sparkling boots. Tony’s graduation certificate is dated May 15, 1943, two days before his 18th birthday. Tony was then under U. S. Army Air Corps command and his class had several Army officers and highranking noncommissioned officers. PFC Tony Wojnar couldn’t know at the time how this class would affect his future 12 years later. Previous page: B-25 Crew Chief Tony Wojnar on the Air Guard ramp in Milwaukee, circa 1955. Above: USMC VMB 423 Sgt. Wojnar (back row, left) and crew with their 100 mission PBJ bomber, Green Island, 1945. Back at NAS North Island, he got to work on Marine Corps fighter aircraft, installing armor plate in the cockpits of new F4U Corsairs. Soon he was transferred to attend the factory school at North American Aviation in Los Angeles where the B-25 Mitchell bomber was built. Tony was then under U. S. Army Air Corps command and his class had several Army officers and high-ranking noncommissioned officers. PFC Tony Wojnar couldn’t know at the time how this class would affect his future 12 years later. Tony was back at NAS North Island in October 1943, but not for long, as his next move was to Marine Corps Air Station, Cherry Point, North Carolina. Here he was assigned to Marine Operational Training Group 81, the birthplace of Marine Bombing Squadron VMB 423. The squadron’s aircraft was the North American PBJ, the Marine Corps’ version of the B-25. This is where he was first challenged to put all his training into practice. He reported to the flightline where he was given two assistants with only Aviation Machinists Mate’s training. They were tasked to prepare the assigned PBJ for flight. After the task was accomplished, he signed that the aircraft was ready for flight. He went along on the flight to build confidence in himself. After a few weeks, Tony was assigned the newly formed VMB 423 squadron that had been transferred to MCAS Edenton, North Carolina. There they were trained as a group that consisted of aircrew, aircraft maintenance, armament, medics, cooks, motor pool, administration, etc. Someone must have realized that a PFC should not have to shoulder the responsibilities Tony had as he was informed that a Staff Sergeant would be in charge of the maintenance crew. Tony could now learn from his experience. Tony recalls going on many flights, as they always took a mechanic along to help watch for other traffic when they practiced instrument flying. Some of the flights along the east coast were to look for German submarines. The squadron lost two aircraft and one aircrew while training at Edenton. In January 1944, VMB 423 left the cold and dreary weather for MCAS El Centro, California. Here the aircrews trained in night flying, navigation, and medium and low altitude bombing. They also went to NAS North Island and did torpedo drops. When Tony returned from one of the navigation flights (weekend visit to San Francisco) there was a pile of burned debris where one of the airplanes had been parked. Someone had accidentally fired the nose machine gun in the airplane parked across from it. Training continued and orders for embarkation came in February. The squadron was divided into several groups, and Tony went to Alameda Navy Base in San Francisco to board the escort aircraft carrier USS Prince William. The ship had more than 80 fighter and dive-bomber airplanes on the flight deck and below on the hangar deck. The date was February 20 and as they sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge, the sun was low on the horizon. Now out at sea, Tony went below deck to set up his bunk and visit some friends. While in the restroom, he learned his first lesson in being a guest on a Navy warship. It began when the claxon sounded followed by, “Sailors, man your battle stations!” He was amazed at how the sailors sprang into action and closed the bulkhead doors behind them. This left Tony and others locked down inside for more than an hour. This drill happened 11 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

WWII WISCONSIN Above: Flight Engineer Wojnar and KC-97 in Las Vegas. Next page: Tony at his KC-97 Flight Engineer’s station. every sunset and sunrise, as this is when a submarine has the best view of what it is looking for. After that, he made it a point to be up on the flight deck for the rest of the journey. He did not want to be visited by a torpedo down where his bunk was. They crossed the equator on February 27, and saw the Hawaiian Islands on the horizon one day. The next day they had a Navy destroyer escort, and the rest of the voyage was a zigzag until arrival at the New Hebrides Islands in the South Pacific on March 6, after 15 days at sea. VMB 423’s PBJs flew to Hawaii and then island hopped until they reached Espiritu Santo, an island which is part of the New Hebrides. The squadron ground crews reassembled and went to Luganville airport to rejoin the airplanes and aircrews. One of VMB 423’s airplanes did not return from a local flight in Hawaii. In June 1944, the VMB 423 ground echelon left Espiritu Santo, destination Green Island in the Solomon Islands. They arrived on June 20 and found a deplorable campsite. It was raining, tents were down in mud puddles, and sea bags and shoes were standing in mud and water by morning. There were a lot of insects and lizards. On the evening of June 28, 1944, Tony launched a PBJ on a night bombing mission. It was nearly 2 a.m. when he saw the airplane overhead and heard the In June 1945, Tony flew in a PBJ from Green Island to Manus Island in the Admiralty Islands, then proceeded via USS Sea Scan, an old WWI ship, to San Diego, and then to MCAS Miramar, California. sound of the engines of the airplane returning. He was sitting on a tug on the flightline waiting to recover the airplane when suddenly he saw the sky turn red and heard an explosion as the airplane hit the palm trees at the shoreline of the Green Island lagoon. The airplane came to rest on its back in the water about a half-block from the tent where Tony lived, and the explosion and fire caused the 50-caliber ammunition to explode. None of the aircrew survived. Then, with his assigned aircraft lost, Tony was assigned to another crew. VMB 423 continued its high altitude, medium altitude, night heckling, skip bombing, and strafing missions. VMB 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame 423 lost several other aircrews and aircraft during the war in training and combat. In June 1945, Tony flew in a PBJ from Green Island to Manus Island in the Admiralty Islands, then proceeded via USS Sea Scan, an old WWI ship, to San Diego, and then to MCAS Miramar, California. After processing, he was issued a 30day furlough after which he was to report to MCA Cherry Point, North Carolina. He was told that once he arrived at Cherry Point, he would join a new squadron, help train it, and go back overseas in six months. He went home to Milwaukee on furlough in July 1945. Tony had gone through most of his VMB 423 experiences with crew chief Wally Hillmer, who was also from Milwaukee. Naturally, they had much in common. Tony’s mother would send him the Milwaukee Journal newspaper Green Sheet, and he would pass it on to Wally. While they were both back home in Milwaukee during their furlough, Wally told Tony, “We’re having a party and I want you to meet my sister.” Dad has been grateful every day since he accepted that invitation more than 70 years ago. Dorothy Hillmer, my mother, and Tony would be married on October 2, 1948. They still are. Dad still loves to tell that story! Tony arrived at MCAS Cherry Point in August 1945, and was assigned to another PBJ crew. He was told that he would be going to training to be a flight engineer on the Douglas R5D four-engine transport airplane. Then the Big Day, the day that Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945. Eventually he helped ferry a PBJ to Clinton, Oklahoma, for storage. When they arrived, a man with a bucket of paint painted a big yellow “X” on the nose of the airplane. Its service was over. Sergeant Anthony T. Wojnar was discharged at MCAS Quantico, Virginia, in October 1945, over six months short of his 21st birthday. He was placed into the USMC Reserve, subject to recall until 1952. Tony returned to civilian life in Milwaukee, and one of the first things he did was obtain his high school diploma. He earned his private pilot certificate under the GI Bill at Brown Deer airport, flying Aeronca Champs in 1947. He settled into factory production jobs, marriage, and family life. However, his military experience had changed him forever, and he knew there must be a better vocation for him.

WWII WISCONSIN Then, one day in 1953, he saw an ad in the Milwaukee Journal: “Wanted – Airplane Mechanic”. The position was a full time job in the Wisconsin Air National Guard 126th Fighter Squadron in Milwaukee, the predecessor of the present 128th Air Refueling Wing. The unit had F-51 and AT-6 airplanes. The starting pay was to be about half of what he was earning at General Electric. The supervisors who interviewed him asked who his boss was at GE, because they jokingly said they wanted to hire him and then apply for the job he was leaving because it paid more than they earned! So began Tony’s career in the Wisconsin Air National Guard. He was full time air technician employee number 18. Coincidentally, the unit’s Chief of Maintenance was Captain Paul H. Poberezny, whom just a few months before Tony’s hiring had formed the Exper- Photos courtesy of Tony Wojnar imental Aircraft Association. Tony, like several of the talented people with a passion for aviation who worked for Paul, became one of EAA’s first groups of volunteers. Tony worked on the aircraft assigned to the Air Guard in Milwaukee, including the F-51s and AT-6s, F-86s, and F-89s. Then a B-25 was assigned to the unit to train the F-89 radar operators. Tony was working in the hangar one day when he heard the announcement, “Wojnar, report to the maintenance office.” There, Paul told him they had noticed in his resume that he had been trained on the B-25 at the North American factory school. He was immediately assigned as the crew chief on the B-25, reporting directly to Paul. Paul also told him, “Get the airplane ready. I’m taking the dash one (pilot’s handbook) home tonight, and tomorrow we are going flying.” And they did, and for years afterward. The unit’s first B-25 was eventually replaced with another, and Dad was the crew chief on that. Today it remains mounted at the entrance to General Mitchell International Airport in Milwaukee. He then became the crew chief on the unit’s C-47. He flew many hours with the B-25s and C-47, as he usually went along as the flight mechanic whenever it flew. I once heard Dad tell Paul that he figured he had amassed more hours in the air with Paul than any one individual. Paul replied, “And I always brought you home.” Paul told me many years ago how he appreciated having Dad as his crew chief. “When we were scheduled to take off at 5 a.m., your Dad had to be there at 3 a.m. to make sure the airplane was ready,” he said. The Milwaukee Air Guard converted to Boeing KC-97 aerial refueling tankers, and in 1961, Tony joined the aircrew as a flight engineer. All flight engineers had other jobs when they weren’t flying, and Tony worked in base supply, due to his knowledge of aircraft maintenance and parts. His flight engineer duties took him to many places in the world, until he underwent heart bypass surgery in 1970 that disqualified him from flying. Between his crew chief and flight engineer duties, he flew approximately 4,000 hours. When someone would kid Tony about using taxpayer money to travel to attractive places like Hawaii, Bermuda, and Germany, he would respond, “Just think, that’s my job, and if I don’t go there, I’ll be fired!” Dad gives Mom much of the credit for raising us because of his work hours and travels while my brother Bill and sister Cindy and I were growing up. Mom didn’t drive, but we had fun taking the streetcar and bus to get around. We knew Dad had an important job for which other people depended upon him, and that he was doing it for us. He always managed to be there at the important times in our lives. We don’t think we missed anything. The unit had a KC-97 flight simulator, and Tony was reassigned in 1970 and cross-trained as an integrated system mechanic to maintain it. As a former flight engineer, he also unofficially helped many new aircrew members who wanted to get more time flying the simulator. When the KC-97 simulator left due to the unit’s transition to the Boeing KC-135 jet 13 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

WWII WISCONSIN tankers in 1977, Tony took a position in the Quality Assurance section of the Aircraft Maintenance Squadron. That section served as the maintenance commander’s “eyes and ears” and was the primary technical advisory section in the maintenance organization, assisting maintenance supervision at all levels to evaluate maintenance functions and resolve quality problems to ensure the safety of the aircrews and ground crews. Tony was promoted to the Non-Commissioned Officer-In-Charge of Quality Assurance and a Chief Master Sergeant (E-9) in 1982, the position he held until his retirement on his 60th birthday in May of 1985, with 35 years of service to the nation and state of Wisconsin. Sometimes Tony would cross paths with Marine Corps veterans who served with him on Green Island but he didn’t know at the time. One such veteran was Major General Raymond A. Matera, the Adjutant General of Wisconsin from 1979 to 1989. General Matera was a USMC Sergeant gunner on Douglas SBD dive-bombers at the fighter airstrip on Green Island, and they traveled back to the States on the same ship. Tony was honored with induction into the Wisconsin Air National Guard Hall of Fame at State Headquarters in Madison in March 1990. I followed my father into the 128th Air Refueling Wing. I had the great privilege of serving as an aircraft maintenance officer, executive officer, and squadron commander from 1971 to 1996. To my knowledge, we were among the first father/son members of the unit. During my first years in the Guard, I served alongside many World War II veterans who formed the unit in 1947. Having known them, it is easy for me to understand why the United States and its Allies prevailed. Now, Dad is amongst the very few WWII veterans from the unit who are still with us. He still keeps in touch with the VMB 423 Association, and we both still enjoy reuniting with fellow retirees of the Wisconsin Air National Guard when the opportunity arises. As the saying goes, “Once a Marine, always a Marine” – and built on that was a legacy of leadership in the Wisconsin Air National Guard. The Marine Corps motto is “Semper Fidelis – Always Faithful”. The Marine Corps and Air Force flags fly next to the Stars and Stripes in front of our home at Air Troy Estates. Top: Paul Poberezny and Tony visit their former B-25 at the Davis-Monthan AFB “boneyard” moments before it was towed away and scrapped. That actually occurred when, by chance, they just happened to be there. Above: Tony and Paul Poberezny reminisce about their flying experiences, April 2013. 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Photos courtesy of Tony Wojnar

ASSOCIATION NEWS WAHF Celebrates 70th Anniversary of the End of WWII WAHF Announces 2015 Scholarship Recipients The year 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is highlighting the accomplishments of Wisconsin’s WWII aviators through a series of statewide presentations throughout 2015. WAHF speakers are available to travel to cities throughout Wisconsin, giving presentations that focus on the contributions of our state’s World War II heroes. A tabletop, four-panel exhibit (three of which are shown below) that highlights several of WAHF’s inductees will accompany the presentation. Representatives from service clubs, historical societies, EAA chapters, flying clubs, schools, and more are invited to contact WAHF about making a presentation. Contact Rose Dorcey to request a speaker at rdorcey@wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org or call 920-385-1483. The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame has inducted more than 120 men and women since 1985. Our mission is to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame will award five scholarships to aviation students in 2015. The recipients will be honored at WAHF’s induction banquet on October 24 in Oshkosh. WAHF’s scholarship selection committee recently met at the Community Foundation of North Central Wisconsin in Wausau, where the scholarship funds are administered, earlier this year to review the applications and make selections. The committee selected the following students, and their selection was overwhelmingly approved by the WAHF board of directors. The recipients and award they are receiving are: · Johnathon Ridderbush, Thiessen Field Scholarship, $500. Ridderbush, of Appleton, is an A&P student of Fox Valley Technical College in Oshkosh. · Cole Hamilton, Jerome Ripp Memorial, $500. Hamilton, of Richland Center, is a Flight Operations student at the University of Dubuque. · Michael Peer, Jeff Baum Aviation Management, $500. Peer is in the Bachelor of Applied Studies - Aviation Management program at UW Oshkosh. · Nicholas Morgan, Carl Guell Memorial, $1,000. Morgan, of Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin, is an Aeronautical Engineering Technology and Professional Flight student at Purdue University, West LaFayette, Indiana. · Brady Wojt, EAA Chapter 640/Robert Payzer Memorial, $1,000. Wojt, of Marshfield, Wisconsin, is studying aerospace engineering and mechanics at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. For more information about WAHF’s scholarship program, visit www.CFONCW.org or at the WAHF website at www.WisconsinAviationHallofFame.org. 15 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

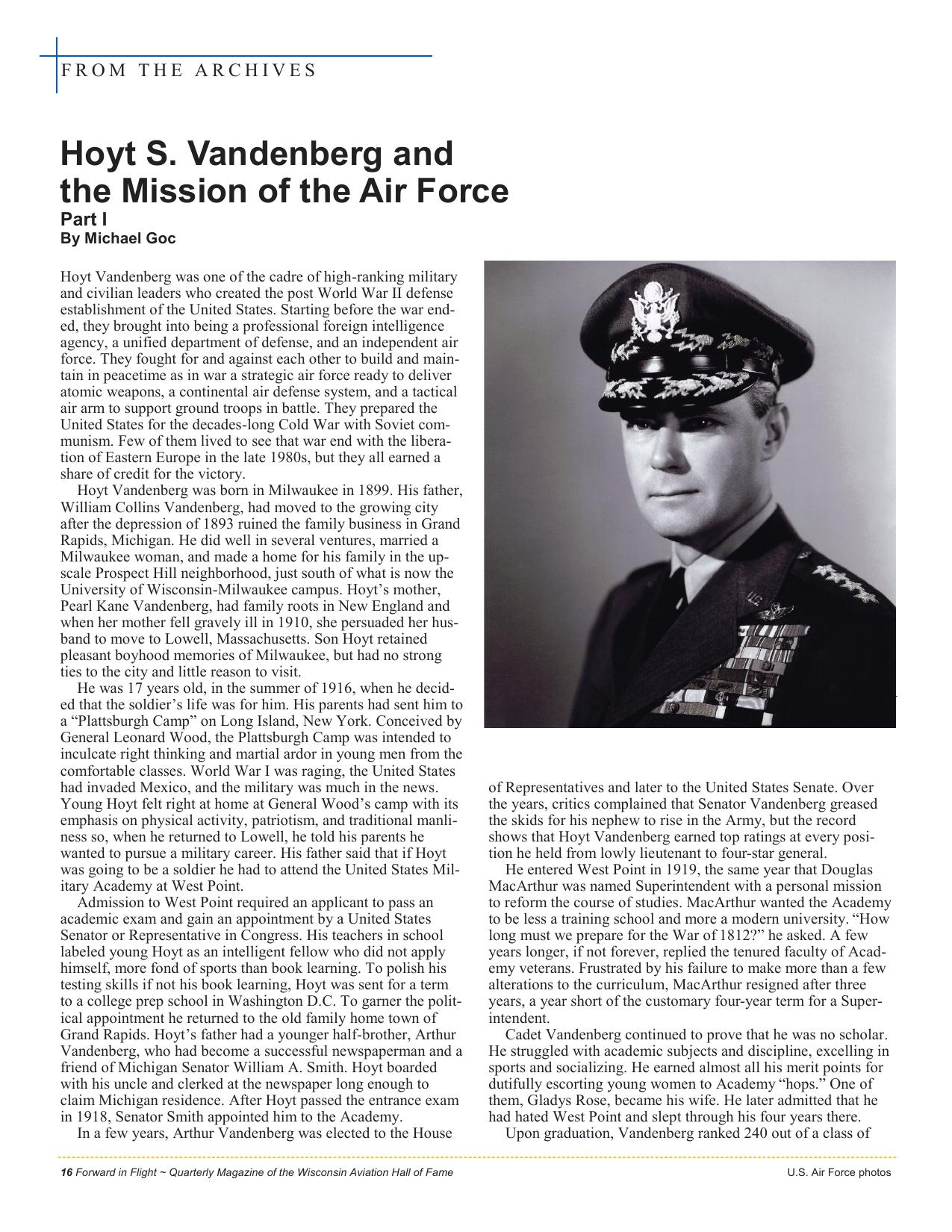

FROM THE ARCHIVES Hoyt S. Vandenberg and the Mission of the Air Force Part I By Michael Goc Hoyt Vandenberg was one of the cadre of high-ranking military and civilian leaders who created the post World War II defense establishment of the United States. Starting before the war ended, they brought into being a professional foreign intelligence agency, a unified department of defense, and an independent air force. They fought for and against each other to build and maintain in peacetime as in war a strategic air force ready to deliver atomic weapons, a continental air defense system, and a tactical air arm to support ground troops in battle. They prepared the United States for the decades-long Cold War with Soviet communism. Few of them lived to see that war end with the liberation of Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, but they all earned a share of credit for the victory. Hoyt Vandenberg was born in Milwaukee in 1899. His father, William Collins Vandenberg, had moved to the growing city after the depression of 1893 ruined the family business in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He did well in several ventures, married a Milwaukee woman, and made a home for his family in the upscale Prospect Hill neighborhood, just south of what is now the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus. Hoyt’s mother, Pearl Kane Vandenberg, had family roots in New England and when her mother fell gravely ill in 1910, she persuaded her husband to move to Lowell, Massachusetts. Son Hoyt retained pleasant boyhood memories of Milwaukee, but had no strong ties to the city and little reason to visit. He was 17 years old, in the summer of 1916, when he decided that the soldier’s life was for him. His parents had sent him to a “Plattsburgh Camp” on Long Island, New York. Conceived by General Leonard Wood, the Plattsburgh Camp was intended to inculcate right thinking and martial ardor in young men from the comfortable classes. World War I was raging, the United States had invaded Mexico, and the military was much in the news. Young Hoyt felt right at home at General Wood’s camp with its emphasis on physical activity, patriotism, and traditional manliness so, when he returned to Lowell, he told his parents he wanted to pursue a military career. His father said that if Hoyt was going to be a soldier he had to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point. Admission to West Point required an applicant to pass an academic exam and gain an appointment by a United States Senator or Representative in Congress. His teachers in school labeled young Hoyt as an intelligent fellow who did not apply himself, more fond of sports than book learning. To polish his testing skills if not his book learning, Hoyt was sent for a term to a college prep school in Washington D.C. To garner the political appointment he returned to the old family home town of Grand Rapids. Hoyt’s father had a younger half-brother, Arthur Vandenberg, who had become a successful newspaperman and a friend of Michigan Senator William A. Smith. Hoyt boarded with his uncle and clerked at the newspaper long enough to claim Michigan residence. After Hoyt passed the entrance exam in 1918, Senator Smith appointed him to the Academy. In a few years, Arthur Vandenberg was elected to the House 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame of Representatives and later to the United States Senate. Over the years, critics complained that Senator Vandenberg greased the skids for his nephew to rise in the Army, but the record shows that Hoyt Vandenberg earned top ratings at every position he held from lowly lieutenant to four-star general. He entered West Point in 1919, the same year that Douglas MacArthur was named Superintendent with a personal mission to reform the course of studies. MacArthur wanted the Academy to be less a training school and more a modern university. “How long must we prepare for the War of 1812?” he asked. A few years longer, if not forever, replied the tenured faculty of Academy veterans. Frustrated by his failure to make more than a few alterations to the curriculum, MacArthur resigned after three years, a year short of the customary four-year term for a Superintendent. Cadet Vandenberg continued to prove that he was no scholar. He struggled with academic subjects and discipline, excelling in sports and socializing. He earned almost all his merit points for dutifully escorting young women to Academy “hops.” One of them, Gladys Rose, became his wife. He later admitted that he had hated West Point and slept through his four years there. Upon graduation, Vandenberg ranked 240 out of a class of U.S. Air Force photos

FROM THE ARCHIVES 260, but it did not hurt him. Although modern arms and artillery, chemical weapons, mechanized vehicles, airplanes, and submarines had vividly illustrated the future of warfare, the top-ranking graduates of Vandenberg’s class of 1923 opted to serve in the cavalry. Vandenberg couldn’t make the cut for horse soldier but, thanks to MacArthur, the class of ’23 was the first to be offered the option of serving in the Army Air Service. After attending a stirring lecture on aviation given by General Billy Mitchell and seeing an Army pilot land an SE 5 Pursuit plane on the Academy grounds, Lieutenant Vandenberg choose to become an aviator. It proved to be the right choice for him, the air force, and the United States. He was sent to the Air Service’s flight school at Brooks Field, San Antonio, then to Advanced Flying School at nearby Kelly Field. His first assignment was to the 90th Attack Squadron, the plum spot for hotshot fighter pilots. Vandenberg was good, he knew it, and he loved it. When Hollywood producers came to San Antonio to film the aviation thriller Wings in 1926, Vandenberg was chosen to pilot the airplane “flown” by star Buddy Rogers. Vandenberg took the plane up with Rogers seated behind, ducked beneath the cowling when the cameras rolled, then reappeared to take control of the airplane. He could have been content to spend his career in the cockpit of an Army fighter, but Hoyt Vandenberg had more in him. The very nature of his first assignment to an “Attack” Squadron pointed out the simple question he would wrestle with for his entire career. What is the mission of an air force? In the early 1920s, the Air Service was divided into Attack, Observation, Bombardment, and Pursuit Squadrons. Attack Squadrons were to go into combat first and take control of the airspace so the others could observe, bomb, and support ground troops, so said the training manual. In the air, missions often overlapped and results were determined less by declared goals than by the limited capability of the aircraft. The high-flying Attack Squadrons, for example, the Pursuit Squadrons, and some Bomber units all flew World War I era DH-4 airplanes. Hardly barnburners. Driven by political events and advancing technology, the mission of the air force was redefined many times over during Vandenberg’s 30 years of duty. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, Vandenberg traveled through a typical military career, with stops in Texas, California, Hawaii, Alabama, and Kansas. Each time he was reassigned to a new squadron, he rose to command it, and then moved on. In Hawaii with the 6th Pursuit Squadron in 1931, he and his men tested the new P-12 fighter. As the story is told, he once led his men in their open cockpit P-12s up to an altitude of 20,000 feet. None of them blacked out, but they all experienced hypoxia, and some pilots collapsed on the runway. Although he might have killed them, his men liked and respected Vandenberg. In fact, his affability with both superiors and subordinates, frequently and positively noted, gave him a leg up throughout his career. Vandenberg was the kind of guy you wanted to have a beer with, preferably after a round of golf, which he enjoyed almost as much as flying. Also, frequently noted throughout his career, and not always positively, were his matinee idol looks. He was tall, slim, blonde-haired and blue-eyed, and as photogenic as a model. Chatty in the officer’s club, he could be taciturn and slow to respond to questions on the job, thereby giving critics an opportunity to dismiss him as a dumb blonde. Attractive women, accomplished or not, were and still are, judged this way, but it was unusual for a man to be so treated. Rivals in the service ribbed him as a pretty boy. When he worked in the Pentagon in the 1940s female secretaries left their desks to leer when he walked down the hall. Time Magazine put him on its cover and the Washington Post dubbed him “the most impossibly handsome man” in the capital. In the 1950s, another not-so-dumb blonde, Marilyn Monroe, said that Vandenberg, along with her husband Joe DiMaggio and physicist Albert Einstein, were the three people she would pick to be stranded with on a desert island. Maybe she liked golf. Vandenberg and his family loved Hawaii, but he knew that if he wanted to move up the career ladder he had to return to the mainland. He found an instructor’s posting at Randolph Field in Texas, known as “The West Point of the Air,” and trained pilots for three years. In 1934, he took part in Franklin Roosevelt’s disastrous venture to use Air Service pilots to deliver the U.S. Mail. More than 60 airplanes crashed and 12 airmen died before it ended. Vandenberg had a Vandenberg flew Boeing P-12 pursuit airplanes in Hawaii and so did the Marine aviators depicted here. near miss when searching for a landing field in a snowstorm over Pennsylvania. He was saved by an ex-Air Corps flyer who heard the plane’s engine and waved a lantern that guided Vandenberg to a mountaintop clearing where he could land. His next assignment, and a very valuable one, was at the Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Field, Alabama. He was in a school setting again, but this time he was studying a subject he loved and with equally passionate colleagues. The basic question had not changed. What is the mission? The Air Corps had just taken custody of its first Martin B-10 bombers, and the experimental model of the B-17 was entering production. These aircraft, as well as airplanes made in Europe, magnified the possibilities of strategic bombardment. The idea of attacking industrial and later civilian targets well behind the battle lines had been around since the days of the German dirigibles over London. Now it was easy to envision vast fleets of bombers penetrating well into an enemy’s homeland and destroying his war making ability without putting Army boots on the ground. It was a revelation to the hotshot fighter pilot. He learned more at his next assignment, the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This was the must-do training course for would-be Army commanders. The curriculum focused on ground warfare, and Vandenberg was reminded of his sleepy days at West Point. He lazed through the course work, but made invaluable contacts with other future commanders, especially Major Carl M. Spaatz. A World War I combat veteran and a few years older, Spaatz and Vandenberg developed 17 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015

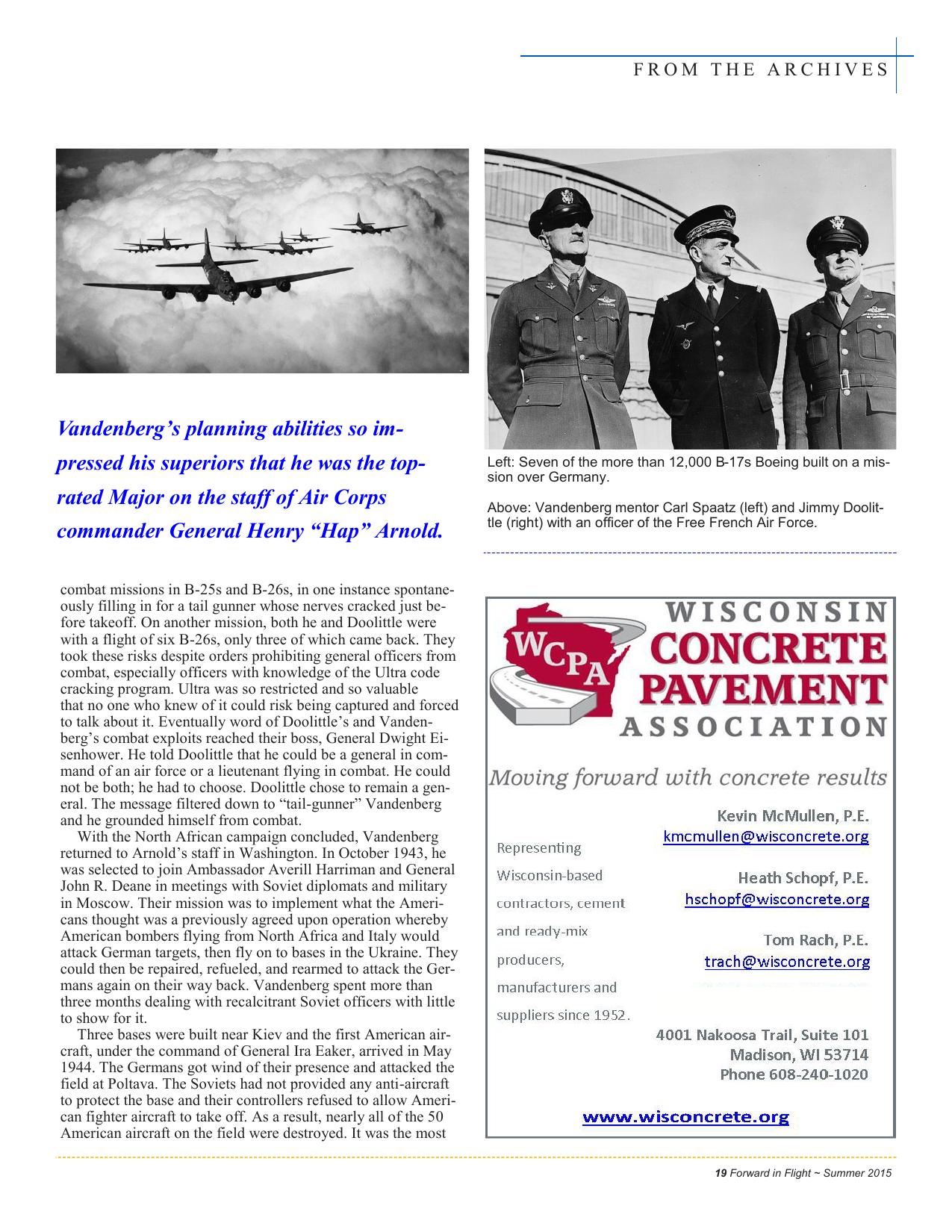

FROM THE ARCHIVES The Martin B-10 bomber, and other long-range aircraft introduced in the 1930s, changed the way air forces thought about strategic bombing. a personal and professional relationship that benefitted them both in the future. Four years into that future, in 1939, Spaatz was named Chief of the Air Corps Plans Section and he brought Vandenberg onto his staff. With war already raging in China and about to begin in Europe, the United States was beginning to expand its military. Vandenberg was ordered to draw up plans for war with Japan. He presented three options: invasion by ground troops, a naval blockade, and strategic bombing from bases on the Philippine island of Luzon. Vandenberg called for a fleet of 900 B-17s to be based on Luzon. They would both defend against a Japanese attack and carry the war to the enemy homeland. They might even act as a deterrent and stop the Japanese from attacking at all. Since the accepted American war plan called for the Philippines to be abandoned in the event of war with Japan, Vandenberg’s plan was a complete reversal, yet it gained support from General George C. Marshall. The United States Air Corps had nowhere near 900 bombers anywhere, let alone for assignment to Luzon, but Marshall ordered a gradual build-up, with more than 300 B-17s and 300 fighters to be transferred to Luzon by March 1942. No more than three dozen made it to Luzon prior to December 8, 1941 and the Japanese soon destroyed most of them. A few other Wisconsin aviators had links to the bomber build-up in the Philippines. WAHF inductee Lester Maitland came to Luzon in 1940 in command of the 28th Bombardment Squadron and had just relinquished the top spot at Clark Field in November 1941. WAHF Inductee Robert Jones was with an Observation Squadron on Luzon in December 1941. His unit was transferred from Clark to Nichols Field to make room for B-17s ordered to Clark. Green Bay’s Austin Straubel was part of a mixed squadron of bombers set to take off from California for the Philippines when the events of December 7-8 altered his course. Vandenberg’s planning abilities so impressed his superiors that he was the top-rated Major on the staff of Air Corps commander General Henry “Hap” Arnold. Promoted to Colonel in 1942, he was the lowest ranking soldier onboard when Marshall, Arnold, and Roosevelt’s top aide Harry Hopkins traveled to London to set up the transfer of 3,000 aircraft to Britain to create what became the Eighth Air Force, under the command of Vandenberg’s patron, Carl Spaatz. When work began on Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa, Spaatz requested and Arnold approved Vandenberg’s posting as chief air planner for Torch and confirmation of his promotion to Brigadier General. He had come a long way in a short time, bypassing officers many years his senior, however, when tested Vandenberg excelled and justified every promotion and honor that came his way. As chief planner for Operation Torch, Vandenberg once again faced the familiar question. What was the mission? His friend Carl Spaatz wanted to restrict his Eighth Air Force to strategic bombing, but Torch required a tactical force and there were only so many bombers to go around. 18 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Spaatz had to divert some of his bombers to the newly created Twelfth Air Force under the command of General Jimmy Doolittle. A true American hero, Doolittle had not pursued a conventional army career and some of the regulars doubted his command competence. Sure, he could raid Tokyo but that did not mean he could run an air force. To hedge his bet, General Arnold reserved the right to name Doolittle’s staff. Bypassing a flock of more senior officers, Arnold named Vandenberg as Doolittle’s Chief of Staff. As it turned out, Doolittle well knew how to run an air force and he got along famously with his Chief of Staff. They created and managed a tactical air force of B-17s, B-24s, B-26s, P-38s, and P-40s to support the landings in North Africa and the combat that followed. No sooner were the Axis armies defeated in North Africa than they shifted the Twelfth to a strategic mission attacking targets in Sicily and Italy. It helped that both men were fighter jocks at heart. Despite their rank, they flew in combat. Vandenberg logged 26 Pam & Pat O’Malley Pat O’Malley’s Jet Room Restaurant Wisconsin Aviation Bldg. Dane County Regional Airport Madison, Wis. (MSN) Breakfast & Lunch 6 a.m. - 2 p.m. Mon. thru Sat. 8 a.m. - 2 p.m. Sunday 608-268-5010 www.JetRoomRestaurant.com U.S. Air Force photos

FROM THE ARCHIVES Vandenberg’s planning abilities so impressed his superiors that he was the toprated Major on the staff of Air Corps commander General Henry “Hap” Arnold. Left: Seven of the more than 12,000 B-17s Boeing built on a mission over Germany. Above: Vandenberg mentor Carl Spaatz (left) and Jimmy Doolittle (right) with an officer of the Free French Air Force. combat missions in B-25s and B-26s, in one instance spontaneously filling in for a tail gunner whose nerves cracked just before takeoff. On another mission, both he and Doolittle were with a flight of six B-26s, only three of which came back. They took these risks despite orders prohibiting general officers from combat, especially officers with knowledge of the Ultra code cracking program. Ultra was so restricted and so valuable that no one who knew of it could risk being captured and forced to talk about it. Eventually word of Doolittle’s and Vandenberg’s combat exploits reached their boss, General Dwight Eisenhower. He told Doolittle that he could be a general in command of an air force or a lieutenant flying in combat. He could not be both; he had to choose. Doolittle chose to remain a general. The message filtered down to “tail-gunner” Vandenberg and he grounded himself from combat. With the North African campaign concluded, Vandenberg returned to Arnold’s staff in Washington. In October 1943, he was selected to join Ambassador Averill Harriman and General John R. Deane in meetings with Soviet diplomats and military in Moscow. Their mission was to implement what the Americans thought was a previously agreed upon operation whereby American bombers flying from North Africa and Italy would attack German targets, then fly on to bases in the Ukraine. They could then be repaired, refueled, and rearmed to attack the Germans again on their way back. Vandenberg spent more than three months dealing with recalcitrant Soviet officers with little to show for it. Three bases were built near Kiev and the first American aircraft, under the command of General Ira Eaker, arrived in May 1944. The Germans got wind of their presence and attacked the field at Poltava. The Soviets had not provided any anti-aircraft to protect the base and their controllers refused to allow American fighter aircraft to take off. As a result, nearly all of the 50 American aircraft on the field were destroyed. It was the most 19 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2015