Forward in Flight - Summer 2017

Volume 15, Issue 2 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Summer 2017 Military at Mitchell World War II-era development Odd Couple to Hawaii Maitland and Hegenberger

Contents Vol. 15 Issue 2/Summer 2017 A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame FLIGHT LOGS 2 Nothing Like that First Airplane Ride Two million success stories - and counting Elaine Kauh, CFI WE FLY 16 100th Anniversary of WWI John Dorcey MEDICAL MATTERS 4 BasicMed ‘Relief from holding an FAA medical certificate’ Dr. Reid Sousek, AME RIGHT SEAT DIARIES 6 Remote Pilot Certification The basics of drone operations Dr. Heather Monthie GUEST AUTHOR 8 Out of the Nest An Alaskan’s flight training in Wisconsin Chris Palmer FROM THE ARCHIVES 10 Wisconsin Aviators Go to War Michael Goc ASSOCIATION NEWS 19 Jill Mann Joins WAHF Board WAHF’s Scholarship 2017 Scholarships FROM THE AIRWAYS 20 Lance P Sijan Memorial Plaza Dedication at Gen. Mitchell International Airport By William Streicher 22 Wisconsin Aviation Conference Summary By Tom Thomas MEMBER SPOTLIGHT 24 James Wood Below: A drizzly, summer rain at the Homer Airport (PAHO) in Homer, Alaska. You’ll find more tailwheel and bushwheels here than most Lower-48 airports. Photo by Chris Palmer.

President’s Message By Tom Thomas Springtime in Wisconsin provides our aviation community with As mentioned, one of this spring’s fun aviation adventures many opportunities to dust off our wings and take off with local was an invitation from the Burnett County EAA Chapter to and regional aviation safety and educational seminars, annual speak on one of their local pilots, Major Richard I. Bong of Popaviation conferences, airport open houses, and fly-ins. lar, Wisconsin, who was born and raised in the Northwest corOne of WAHF’s primary activities is aviation education ner of our state. The date had been set as Saturday, May 13 at and we do that by making presentations on all aspects of aeroVoyager Airport, and a turnout of about 70 attending. An eldernautics, as well as participating in aviation conferences, semily woman from Superior came with her son, bringing an envenars, and weekend fly-ins around the state. lope of newspaper clippings on Bong’s flying accomplishments This spring has been especially busy for us with board from the Superior Newspaper during WWII. Two Superior resimembers participating in EAA Young Eagle flights, both dents that I’d worked with in the past at the airport, Bill ground and flying sides, attending airport open houses, airAmorde, as the airport’s longtime manager, and Bob Mertz, a shows, AOPA Flight Safety programs, and visiting local high fellow CAP pilot and WisDOT Airport Inspector. Interestingly, schools sharing aviation career material. Talks were given on Bob was the only one present who had attended Dick and Richard I. Bong, Wisconsin’s ACE of ACEs, in Burnett County; Marge’s wedding at the Concordia Lutheran Church on Februat the History Round Table in Madison; and at the Milwaukee’s ary 10, 1945. Not to be outdone, Bill was crowned “The Best War Memorial “Bong Awards” program. Other talks included Dressed” attendee (see below). Women Over Wisconsin in Manitowoc to the Wisconsin 99s, Clear Skies and Tailwinds. and a program on Billy Mitchell, Lester Maitland, Austin Straubel, and Richard Knobloch in Fond du Lac. We also had a booth at the 62nd Annual Wisconsin Aviation Conference hosted by Waukesha County Airport/Crites Field. Additionally, we participated in WAHF’s aviation scholarship selection process. Every event attended was a furthering of WAHF’s mission and it has truly been an active, fun spring for your WAHF Board. One of our goals for 2017 is to exceed last year’s memberships and we’re already within reach, hopefully by this publication. Here’s a chance for you to help your WAHF organization grow by sharing the good aviation news. Included in each magazine is an application form that you can use to sign up one of your friends or a family member to a year’s WAHF membership for just $20. It could be as a birthday gift, a reward for achieving a personal goal like soloing, passing an FAA written exam, or obtaining a pilot certificate. Forward in Flight would be something the recipients would receive four times a year, filled with aviation stories, photoWAHF President Tom Thomas with Bill Amorde (center), who will be inducted into graphs, and announcements about aviation WAHF in October 2017, and Bob Mertz, longtime WAHF member. events across Wisconsin. Forward in Flight The only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s events. Rose Dorcey, editor 3980 Sharratt Drive Oshkosh, WI 54901-1276 Phone: 920-279-6029 rdorcey@wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. On the cover: In Alaska, fall is but a few magical, colorful weeks, according to photographer Chris Palmer, who shot this scene right outside his office window in Homer, Alaska. Read more about Chris and his flight training in Wisconsin on pages 8-9. Photo by Chris Palmer

FLIGHT LOGS Nothing Like That First Plane Ride Two Million Success Stories – And Counting By Elaine Kauh The sheer excitement of flying, in and of itself, is so appealing that there’s no way to exaggerate it. It’s fun, thrilling, and always a dynamic process. And if that weren’t enough, taking passengers flying just adds to the fun to a level that, well, makes you want to do it again and again. Few aspects of grassroots aviation can compare to the rewards of taking someone—anyone—for his or her first airplane ride. Whether it’s a friend, family member, or even someone you have never met, giving airplane rides is a favorite flying activity. Spending a few hours giving plane rides to strangers you’ll likely not see again might not seem to be the most fulfilling experience, but it’s quite rewarding. Over the years, I’ve had the pleasure of flying dozens of rides for visitors during local weekend fly-ins. On a sunny day, crowds of people will come to the airport, sign up for a 15-minute ride, and have a wonderful time, with memories that will last a lifetime—all for $25 to $30. Along with the ability to share the fun of flying, the other special aspect of Airplane Ride Day is the fact that nearly all the passengers, adults and kids alike, have never gone up in a small airplane. I’m certain this is true because I always ask my passengers, “Is this your first time?” Some have had the experience before at similar events, but oftentimes it has been a few years or more. Here’s how it works: A handful of pilots on duty for the day remain strapped into the cockpit as helpers board passengers, providing the required briefings on seat belts and door latches. Once given the all-clear, the pilot starts up and taxis out, usually following another ride plane to the designated runway. After takeoff, you’re climbing while joining the circular route each plane follows to give a view of the area. Events like this nearly always have designated 15- to 20-minute routes selected on that day’s weather conditions, so that the airborne traffic will flow logically to a runway that’s aligned into the wind. We generally fly 1,000 to 1,500 feet above the ground as our passengers have a good look around and take pic- tures of the view. We land, roll up to a crowd of onlookers, and everyone gets out with big smiles and what can only be described as energetic excitement. That’s hard to top, but it gets better! How does it feel to take a young passenger, perhaps 10 or 12 years old, flying for her first time, and watching her curiosity and enthusiasm bloom as she sits beside her pilot, looking up and down and all around? And when you’ve landed and parked, what can compare to the smile on her face and the lifelong memory you’ve just created for her? And then, once we’ve captured photos and said goodbye, it’s off to fly the next young person waiting for his firstever flight. And the next, until every kid who has signed up for a ride that day has gone flying with the most generous of pilots – those who gladly give their time, fuel, and the seats in their airplanes to give kids a taste of what flying means to us. This is what happens around the country just about every weekend when a 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame local EAA chapter hosts a Young Eagles event. Young Eagles is one of the best known, longstanding programs of the Experimental Aircraft Association, recruiting volunteer member pilots to provide introductory plane rides to youth ages 8 to 17. Flights can take place by individual appointment, but most of the larger numbers occur at weekend rallies, during which groups of pilots will gather and fly dozens of waiting Young Eagles until every child has had that wonderful experience. They go home afterwards with a personalized logbook and certificate, which the pilot signs. Each flight is entered in the World’s Largest Logbook, which includes the names of each Young Eagle, pilot, and aircraft. In May, EAA celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Young Eagles program with the bonus of exceeding the program’s original goal. According to EAA (eaa.org/youngeagles), the initial goal was to give rides to a million kids by 2003. As of this writing, 2,029,832 Young Eagles have flown, according to

FLIGHT LOGS the association. It just so happens that this landmark year is my first as a Young Eagles pilot. I volunteered for my first rally in April for EAA Chapter 252 in Oshkosh, which hosted a fly-in breakfast the same day. It was a cool, breezy day with sunny skies, and the famous north-south runway (8,002 feet) allowed aircraft to come and go without a crosswind. On this day, I had a small Piper airplane that allowed me to take pairs of Young Eagles for each flight. This turned out to be a great arrangement because three of the four rides I flew were for brother-sister siblings, which made for lots of fun and some great photos. I used a few tips from the advice the experienced volunteers gave me: Take a few moments to introduce the airplane after introducing yourself. Before walking out to the ramp, ensure that everyone, parents included, understand to follow their pilot or CAP escort, and stay well clear of propellers or moving aircraft. Conduct a short (and legally required) briefing of how to use seatbelts, doors, and windows. I also added reminders to look out the window as much as possible to both watch for other aircraft and to get the most out of the flight. I also tried to engage each one by asking them to assist with small tasks, such as pushing in the mixture knob during my startup procedure or pressing a button to tune a radio. They were happy to oblige. One or two of the more loquacious ones, ironically, asked lots of questions, and then confessed they were “a little scared.” So, I’d say that I’ll promise to keep an eye on everything and check on them every few minutes. Once airborne, I’ll turn to them and ask, “this isn’t too bad at all, is it?” Invariably, they’ll look over and nod, having forgotten that they were supposed to be “a little scared.” The look of achievement afterwards, when I tell them what a great job they did as my co-pilot, is priceless. Oshkosh’s Wittman Regional Airport was a great place for me to launch my Young Eagles pilot career. After receiving a takeoff clearance, I’d direct everyone’s attention to the blue dot on Runway 18 and say, “We’re going to speed up towards that dot on the runway and be in the air before it!” During final approach to the runway, I also had them watch the same blue dot, saying we’d be landing right on it. (This was also great practice for me, as I could practice touchPhotos courtesy of EAA Chapter 572 The author and one of the two-million-plus Young Eagles. Previous page: Young Eagles flights offer the best of grassroots aviation; a chance to show youth a bird’s-eye view of the world and the fun of piloting small airplanes. ing down right before the dot and was able to exit the runway without holding up traffic.) In May, I volunteered for my second rally, this time at nearby Fond Du Lac for EAA Chapter 572. It was another windy day and my bird was a lighter, smaller Cessna 152, but we again had a runway in our favor and more than 80 Young Eagles received rides with their volunteer pilots. I was the newbie volunteer pilot. Among each group, we had several longtime Young Eagles veterans who have given hundreds of rides over the years. They arrived at the pilot briefings ready to go and, even after flying so many Young Eagles, excited to see all the kids lined up for their rides. It takes far more than a pilot and a plane to make these rallies so successful. Dozens of other volunteers, including those from EAA chapters and the Civil Air Patrol, put in countless hours for the program. They plan and coordinate the events, serve food, park airplanes, sign in and sign out each Young Eagle, and ensure everything is done as safely as possible. Another great aspect of giving kids rides in a formal program like this is the follow-up. Every young passenger, in addition to the logbooks and certificates, receives free resources from EAA, including a student membership and access to an online learn-to-fly course. They can also register for future additional flights through the program and collect more entries in their Young Eagles logbooks. A fellow EAA member and longtime volunteer pilot told me that a young person who continues to express interest in aviation and flies multiple times with the volunteers is more likely to learn how to fly or otherwise start a pathway into aviation. And that’s the ultimate plus for this program and for any pilot who has given a kid a plane ride: it plants the seed. And if other generous aviation enthusiasts, pilots, and supportive family members can nurture these seeds into a tangible interest in the field, we’re doing our part to show young people the door to endless possibilities in aviation, whether they become private or career pilots, aircraft builders, or any one of the numerous professions this field has to offer. That 15 minutes in an airplane goes such a long way. Elaine Kauh is a flight instructor and aviation writer who enjoys flying around Wisconsin and elsewhere. E-mail her at ekauh@wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org. 3 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

MEDICAL MATTERS BasicMed ‘Relief from holding an FAA medical certificate—for certain pilots’ Dr. Reid Sousek, AME This article is a useful and timely review of BasicMed, the new FAA plan related to third class medical reform. The FAA’s number one answer in the FAQ section clarifies that they, the FAA, did not develop these requirements. The U.S. Congress developed them, the FAA is simply implementing those provisions. Operating under BasicMed rules is voluntary. You may continue to apply for and operate under 3rd class guidelines. The basics of BasicMed are quite simply stated on the FAA website: Comply with the general BasicMed requirements (possess a valid US driver’s license, and have held a medical certificate after 7/14/2006) Get a physical exam with a state-licensed physician, using the Comprehensive Medical Examination Checklist Complete a BasicMed medical education course Go fly! Operating under BasicMed limits the aircraft you can fly. These rules apply only to an aircraft authorized to carry not more than six occupants and with a maximum certificated takeoff weight of not more than 6,000 pounds. Obviously, if the aircraft can carry six occupants, you can take five passengers with one pilot. You may operate under VFR or IFR within the U.S. but not above 18,000 feet MSL and not over 250 knots. You also may not fly for hire. So, the next time you sit in seat 17F on a Southwest flight to Orlando, you are not in the hands of a captain flying under BasicMed criteria. Operations that require a 1st or 2nd class medical certificate will still require those appropriate certificates. To qualify for BasicMed, a pilot must have held a valid FAA medical certificate for at least one day after July 14, 2006. Additionally, the most recent certificate must not have been denied, suspended, revoked, or lost any special authorizations. If you chose to let your certificate lapse after that date, it is not a problem. But if the medical certificate was taken away or you applied for another medical, and were not able to be issued, then you would not qualify. If your previous certificate was suspended, but later reinstated, you must obtain a new medical certificate to operate under BasicMed. The wording here is specific “cannot have been…suspended”. If your last application hit some turbulence, it will be critical to review the last letter received from Aerospace Medical Certification Division (AMCD). Let’s go through a case example. Five years ago, you applied for a medical and went through the exam. Your AME issued or deferred and you received a letter from AMCD requesting additional information. Let’s say the required additional info seemed like a lot and some of the testing was not covered by insurance, so you just decided to ignore the letter. These letters usually give you a certain timeframe (60 days) to submit the required info. If this is not received by AMCD, you are then denied. In this situation, where you did not submit the additional required documentation, you would be denied even though you may have been qualified if proper testing 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame or documentation was submitted. Read the fine print of the FAA letters. If you completed a previous MedXPress application but never presented for exam (or never provided the AME with the confirmation number for importing), you never had an exam in the eyes of the FAA. Another important time to read the fine print from the FAA is if you were on a special issuance. This is important when considering the key 10 year look back date of 7/15/2006. Generally, a special issuance will be valid for less time than a “free and clear” medical. For example, a 35-year-old pilot, without a special issuance, would generally have a valid 3rd class medical for five years (higher class exams lapse into lower classes, so 2nd class for 2 years or 1st class for 1 year and even shorter time frames once over 40). However, on a special issuance, the certificate will have “Not Valid for Any Class After MM/ DD/YYYY”. Look closely to make sure you did hold a valid medical at some point after July 15, 2006. If you choose to proceed with BasicMed, there will be a form that will need to be signed by your physician. The Comprehensive Medical Examination Checklist can be found on the FAA website. This 9-page form has portions for the airman to complete and for a state licensed physician to complete. This may bring up a few issues for some. For example, many individuals don’t have a physician or primary care provider. Many young and healthy individuals do not go in for routine checkups and are therefore not an established patient of any provider. A physician that you have not seen before may not be comfortable signing this form after a single 10-minute visit and without review of previous records. The other issue is that, while you may have a primary care provider, they may not be a physician. The FAA is specifically requiring a state licensed physician (MD or DO) to ultimately sign the checklist. It does not appear that Advanced Practice Clinicians (PA or NP) can perform the exam or sign the form at this time. It would be best to communicate with your providers, prior to the visit, that you are interested in completing this type of exam. It may be a lot to ask of your doctor to complete this form without allowing adequate time to review it. This Examination Checklist will need to be completed every 48 months. Every two years, an online medical education course must be completed by the Airman. The medical examination may be required prior to taking the online education class. The medical course registration will require information including the name and license number of the physician completing the medial exam. Your personal information will also be used to check the National Driver’s Registry. Those who self-certify through the BasicMed program also imply that they understand 14 CFR 61.53 – Prohibition on Operations During a Medical Deficiency. The legalese of this can be found online, but the key is that you cannot act as Pilot-inCommand (or required crewmember) if you know or have reason to know of any medical issues that would make you unable to meet requirements medically for pilot operation. Additional-

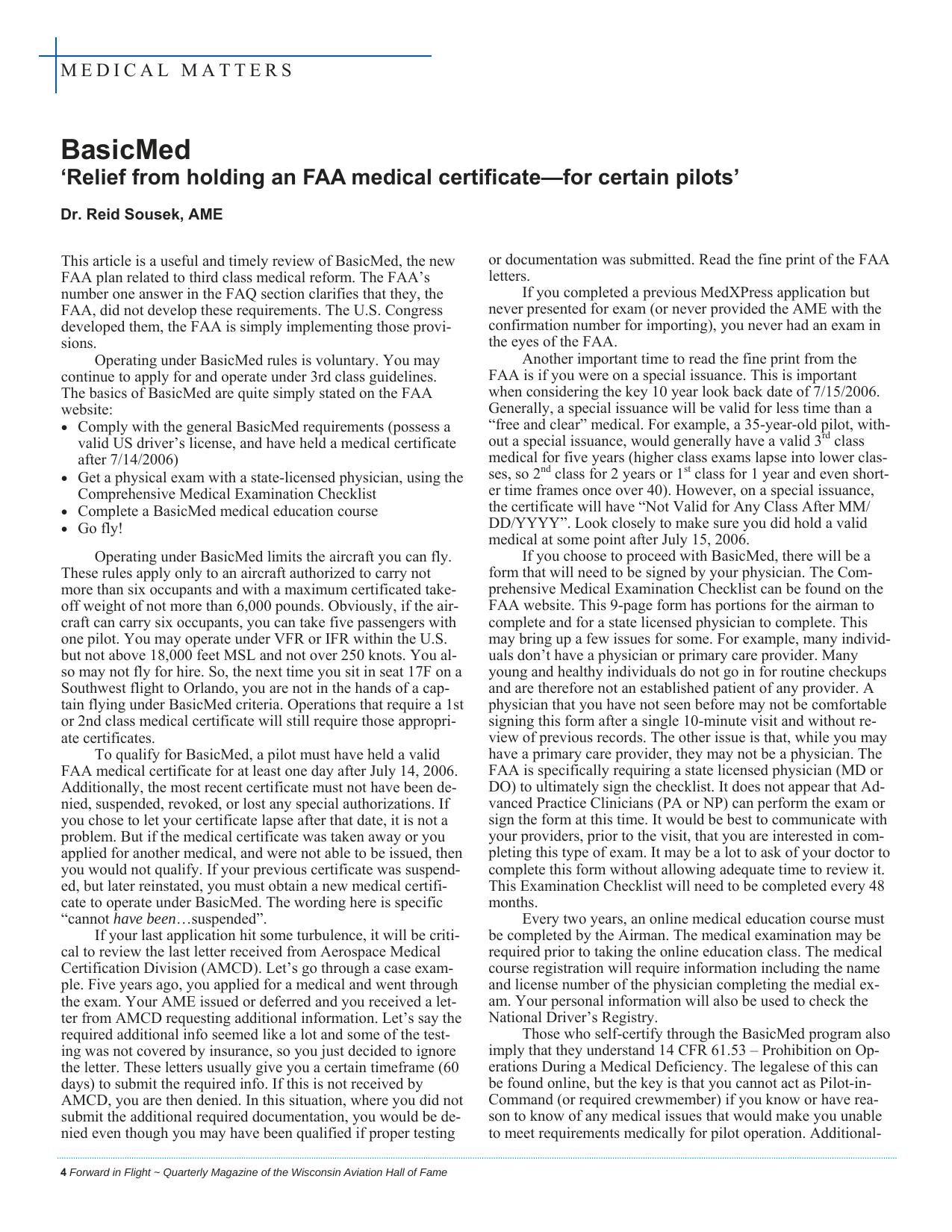

MEDICAL MATTERS The FAA website outlines its BasicMed provisions so you can make an informed decision. ly, you may be prohibited if you are taking a medication or receiving treatment for a condition that makes you unable to meet those requirements. This is where the online medical education courses will help you understand your health conditions better (also you can further supplement your aeromedical knowledge by continuing to read these columns). While you must keep your copy of the Comprehensive Medical Examination Checklist and medical education course completion certificate available upon request (with your logbook), you do not have to carry it with you while flying. To meet BasicMed requirements, all you would need is a valid driver’s license (other documentation to fly such as a Pilot Certificate are covered under separate regulations and would also be needed). A U.S. Passport does not meet criteria for a driver’s license nor does an international driver’s license. Any restrictions on the driver’s license (i.e. corrective lenses, prosthetic aids, daylight driving only) also apply to flying. What about just seeing your previous AME and having them complete the Comprehensive Medical Examination Checklist? This will be dependent upon your AME. In some rare cases, your AME may also be your family physician. In most cases, however, your AME does not wear both hats. Some AMEs may choose not to do the BasicMed exams. The reason is that for most AMEs, we are functioning as a designee of the FAA. In this role, we are not establishing a Physician-Patient relationship. By completing this form, the provider is being considered a treating physician. This may seem like a matter of semantics; however, the AME’s malpractice carrier or lawyer may feel otherwise. Another consideration I read in an email sent from Dr. Schall (Great Lakes Regional Flight Surgeon) is that since the airman does not have a Medical Certificate, he may risk surrendering his Pilot Certificate if found in violation. The FAA retains the authority to suspend your certificate (49 U.S.C 44709 (a)). All this seems like a major risk and hassle, but it is not any more of a hassle than a Biennial Flight Review. There are some specific exceptions that would require an airman to obtain an Authorization for Special Issuance of a Medical Certificate: a Mental Health disorder, Neurological disorder, or Cardiovascular conditions. These three special situations are taken from the FAA BasicMed website: Mental health disorders include personality disorders that have been severe enough to have been repeatedly manifested in overt acts such as psychosis, bipolar disorder, or substance dependence in the past two years; Neurologic disorders include: epilepsy; disorder of consciousness without satisfactory medical explanation; or, transient loss of control of the nervous system; Cardiovascular conditions, like myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease that has required treatment, cardiac valve replacement, or heart replacement might require onetime special issuance. What percentage of the thousands of the current 3rd class applicants will switch to the BasicMed remains to be seen. The over-riding point to drive home is to not take this lightly. Make sure you fully understand what you are signing and that you truly meet the requirements. A lot can change during the four years between comprehensive exams, so use the resources available to help make an honest self-assessment before you self-certify or fly. BasicMed class dismissed. Links: BasicMed overview; www.faa.gov/licenses_certificates/airmen_certification/ basic_med) The FAA’s comprehensive Medical Examination Checklist: https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Form/ FAA_Form_8700-2_.pdf). Special Medical Situations: https://www.faa.gov/licenses_certificates/airmen_certification/ basic_med. 5 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

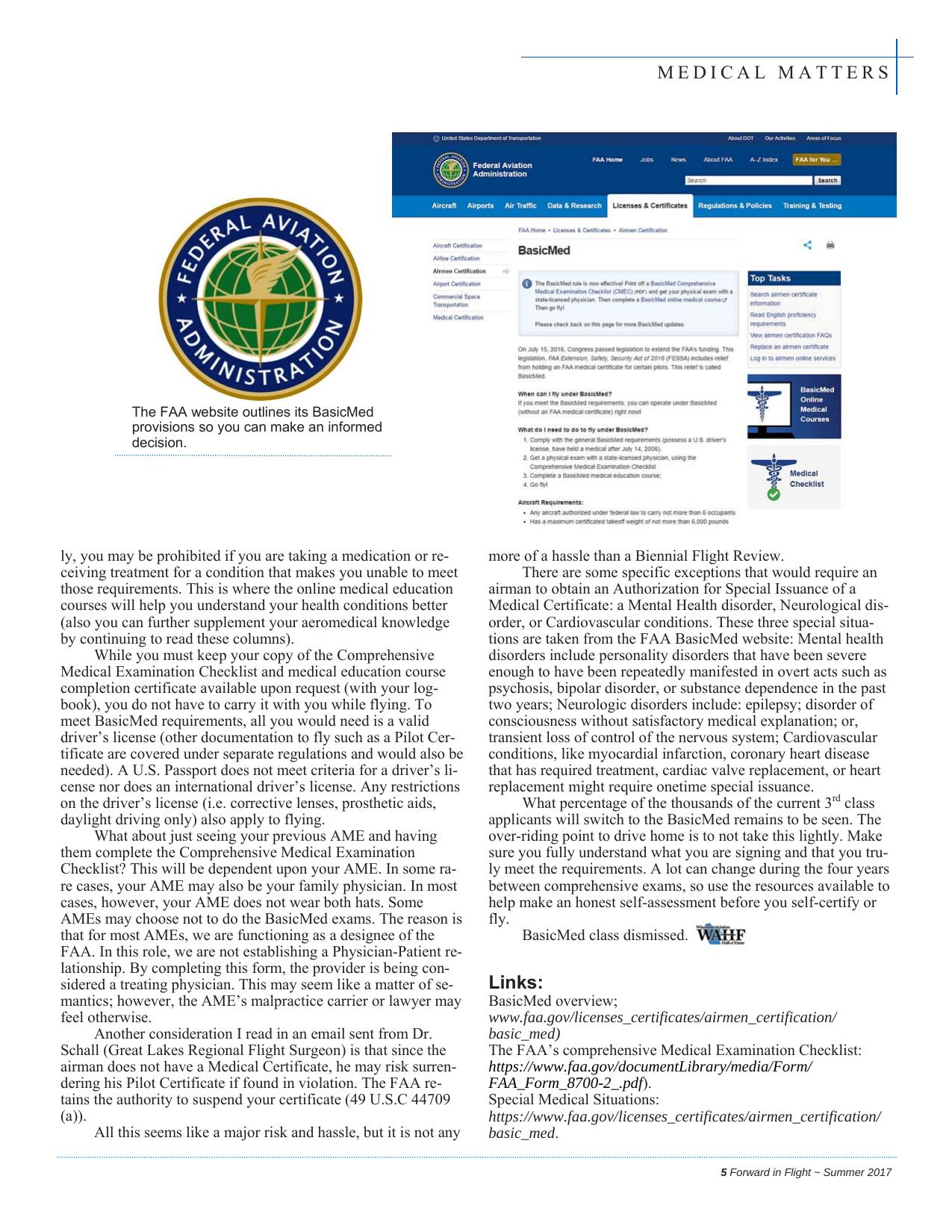

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES Remote Pilot Certification The basics of drone operations By Dr. Heather Monthie It appears we hear increasingly more about drone flying. It’s interesting to see how drones are bringing more people to aviation due to their affordability. I’m part of many aviation and remote pilot groups and it’s a bit sad to see the negative opinions many airplane pilots have of remote pilots, largely due to a lack of education on the bigger picture of aviation safety, airspace rules, and proper etiquette. It’s my intention to help welcome new people to aviation and to provide proper education. Drones are technically called small unmanned aerial systems, or sUAS. You will see that official term used throughout FAA documentation and I will use sUAS throughout this article. What is the remote pilot certification? The remote pilot certification allows the operator to fly a sUAS for commercial purposes. This is intended for individuals using the sUAS outside of hobby or recreational use. Some may want to use their sUAS for commercial photography, aerial surveillance, videography, or other forms of business. If you intend to use your sUAS for commercial purposes, you must have a remote pilot certification. How does one become a remote pilot? There are a couple different routes to get your remote pilot certification, depending on your previous flying experience. If you are already a certificated pilot, you can take a short online course through FAASafety.gov. I took it a while ago and could complete it in a few hours. The course covers the content in Part 107 of the Code of Federal Regulations, which is the operating rules for sUAS. The course for certificated pilots does not go nearly in depth on most areas, simply because those topics are covered in your previous flight training. This course will really help you to understand the operating rules for sUAS and what might be different compared to what you normally fly. Once you have successfully completed the course, you can present your documentation at your local Flight Standards District Office to obtain your remote pilot certification if you have a current flight review. See FAA.gov for more specifics on the documentation you must provide and the process to follow to obtain your certification. If you do not hold any pilot certifications, you have a few different steps to take in order to obtain your remote pilot certification. You are required to pass the initial aeronautical knowledge exam. This exam is different from the course the current pilots must take. In fact, you don’t necessarily need to even take course - although I do highly suggest it! The exam must be taken at an approved FAA knowledge test center. There is a list of centers available on FAA.gov. There are quite a few centers throughout the country, so even if you live in a rural area you may be able to find one close to home. The knowledge test covers the following areas (from FAA.gov): Regulations relating to sUAS rating privileges, limitations, and flight operation Airspace classification and operating rules 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame This Phantom 4 Pro by DJI is easy to operate right out of the box. Whether for hobby or commercial use, there are dozens of models to choose from. There’s also much to know, and resources to teach you, about safe drone flying practices. Aviation weather sources and its effect on flight performance Loading and performance Emergency procedures Crew resource management Radio communications Determining performance Effects of drugs and alcohol Aeronautical decision making Airport operations Maintenance and pre-flight operations Preparing for the exam Your first stop for any FAA knowledge test is to download the certification standards from FAA.gov. On the “Remote Pilot Knowledge Test Prep” page, there is a link at the top to a PDF Photos by Luke Parmeter

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES of the Airmen Certification Standards. This is everything you are expected to know for the initial aeronautical knowledge exam and to operate your sUAS. The airmen certification standards document is not intended to be a study guide, but more of a list of areas you’re expected to know. You can get information on each of these areas from the various resources linked on that page, such as the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge. It is definitely a good idea to take either an online or faceto-face course to prepare you for the initial aeronautical knowledge exam. While this is not a requirement to take a course, it will most certainly help you. In my quest for information while surfing the Internet, I found that there are some good online references, but like anything, there are some that may not be the best source of information for you. Some training centers offer actual flight operations training as well to show you how to properly operate your sUAS. This is also not a requirement, but would be helpful if you have no prior operational experience and probably don’t want to damage your new piece of equipment! And there’s nothing wrong with purchasing an inexpensive drone to get your feet wet before moving on to a more sophisticated piece of equipment. There are a lot of Facebook groups that I have found that help answer study questions relating to this exam. It’s my observation that most of the questions and test anxiety are around airspace rules and how to read sectional charts. Even as I was studying the sample test questions, there were a lot of questions in this category. It is important to understand the National Airspace System, how it relates to you as a remote pilot and how other manned aircraft may be operating in the same airspace. It appears that sometimes remote pilots get a bad reputation among aircraft pilots when they are operating a sUAS in airspace in which flight operations are prohibited. It is imperative that you understand that you may be living in an area where you simply cannot operate your sUAS in your backyard due to airspace restrictions. You can also head to my website at www.AdventurousAviatrix.com. I am beginning to add more content for remote pilot certification and sUAS flight operations. This fall, the site will have quite a bit more information to help you learn, pass the exam, and then continue learning! tion of any airspace restrictions. Again, it’s always good to know if you can’t operate your drone in your own backyard! What can I do with my sUAS? Flying a drone or sUAS can be a lot of fun. There are a lot of cool things I have seen over the past several months. At the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, drones seem to be one of the more popular areas of the convention. While there, I saw tiny drones with cameras that were marketed as a new way to take selfies. I saw drones with sonar capabilities with the idea that they can be used for fishing or treasure-hunting beneath the water. This could also be used for search and rescue missions. In my passion for promoting STEM education, I am always looking for ways to share aviation with young people. I am also very involved in promoting computer science education to high school students. Part of my recent activities is to use drones to teach more about how to write code, understanding rules and logic, and teach drone safety. As increasingly more young adults receive drones as gifts, this is a great mechanism to teach them about aviation, coding, robotics, design, and more! The future of sUAS As these devices continue to evolve, we will need to stay up-todate on current events and possible changing regulations. Technology often changes faster than policy, so it’s important to know and understand your device and operate in a safe manner. It’s exciting to see all the new functionality and capabilities. I would love to hear more from you! You may contact me on my website at www.AdventurousAviatrix.com or on Twitter at @DrMonthie. Who can obtain the remote pilot certification? To take the initial aeronautical knowledge exam, you must be 16 years old, be able to speak, read, write, and understand English, be in a physical and mental condition to safely operate a sUAS. The certification must be renewed every two years. When do I need to get my remote pilot certification? Remote pilot certification is needed when you are intending to fly your sUAS for commercial purposes. Some use their sUAS for aerial photography, surveillance of accidents or natural disasters, surveying roofs of buildings, and other modes of operation that are not purely recreational. If you are operating for recreational or hobby purposes, it isn’t required for you to operate. It is still important for you to obtain proper training on flight operations to ensure that you are not in viola7 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

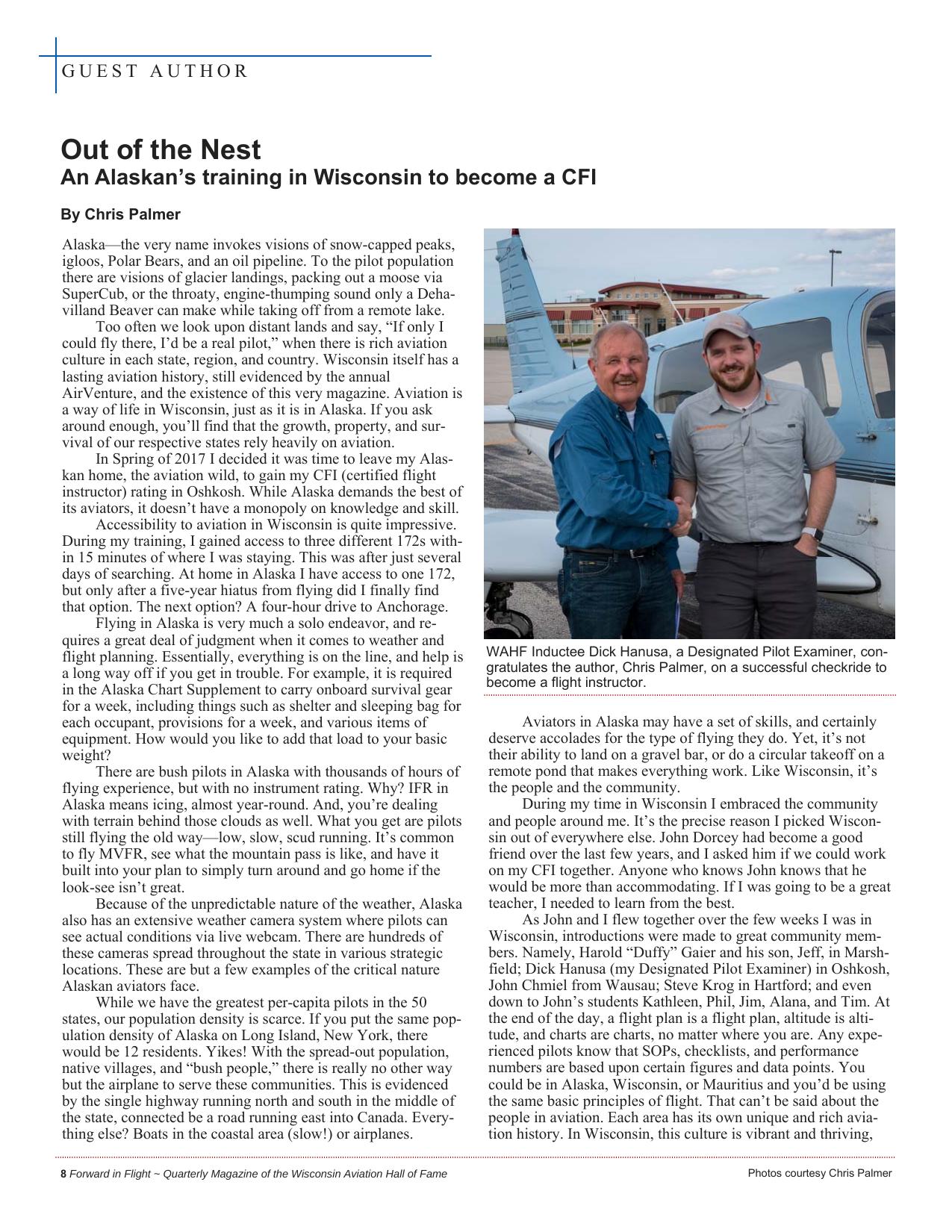

GUEST AUTHOR Out of the Nest An Alaskan’s training in Wisconsin to become a CFI By Chris Palmer Alaska—the very name invokes visions of snow-capped peaks, igloos, Polar Bears, and an oil pipeline. To the pilot population there are visions of glacier landings, packing out a moose via SuperCub, or the throaty, engine-thumping sound only a Dehavilland Beaver can make while taking off from a remote lake. Too often we look upon distant lands and say, “If only I could fly there, I’d be a real pilot,” when there is rich aviation culture in each state, region, and country. Wisconsin itself has a lasting aviation history, still evidenced by the annual AirVenture, and the existence of this very magazine. Aviation is a way of life in Wisconsin, just as it is in Alaska. If you ask around enough, you’ll find that the growth, property, and survival of our respective states rely heavily on aviation. In Spring of 2017 I decided it was time to leave my Alaskan home, the aviation wild, to gain my CFI (certified flight instructor) rating in Oshkosh. While Alaska demands the best of its aviators, it doesn’t have a monopoly on knowledge and skill. Accessibility to aviation in Wisconsin is quite impressive. During my training, I gained access to three different 172s within 15 minutes of where I was staying. This was after just several days of searching. At home in Alaska I have access to one 172, but only after a five-year hiatus from flying did I finally find that option. The next option? A four-hour drive to Anchorage. Flying in Alaska is very much a solo endeavor, and requires a great deal of judgment when it comes to weather and flight planning. Essentially, everything is on the line, and help is a long way off if you get in trouble. For example, it is required in the Alaska Chart Supplement to carry onboard survival gear for a week, including things such as shelter and sleeping bag for each occupant, provisions for a week, and various items of equipment. How would you like to add that load to your basic weight? There are bush pilots in Alaska with thousands of hours of flying experience, but with no instrument rating. Why? IFR in Alaska means icing, almost year-round. And, you’re dealing with terrain behind those clouds as well. What you get are pilots still flying the old way—low, slow, scud running. It’s common to fly MVFR, see what the mountain pass is like, and have it built into your plan to simply turn around and go home if the look-see isn’t great. Because of the unpredictable nature of the weather, Alaska also has an extensive weather camera system where pilots can see actual conditions via live webcam. There are hundreds of these cameras spread throughout the state in various strategic locations. These are but a few examples of the critical nature Alaskan aviators face. While we have the greatest per-capita pilots in the 50 states, our population density is scarce. If you put the same population density of Alaska on Long Island, New York, there would be 12 residents. Yikes! With the spread-out population, native villages, and “bush people,” there is really no other way but the airplane to serve these communities. This is evidenced by the single highway running north and south in the middle of the state, connected be a road running east into Canada. Everything else? Boats in the coastal area (slow!) or airplanes. 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame WAHF Inductee Dick Hanusa, a Designated Pilot Examiner, congratulates the author, Chris Palmer, on a successful checkride to become a flight instructor. Aviators in Alaska may have a set of skills, and certainly deserve accolades for the type of flying they do. Yet, it’s not their ability to land on a gravel bar, or do a circular takeoff on a remote pond that makes everything work. Like Wisconsin, it’s the people and the community. During my time in Wisconsin I embraced the community and people around me. It’s the precise reason I picked Wisconsin out of everywhere else. John Dorcey had become a good friend over the last few years, and I asked him if we could work on my CFI together. Anyone who knows John knows that he would be more than accommodating. If I was going to be a great teacher, I needed to learn from the best. As John and I flew together over the few weeks I was in Wisconsin, introductions were made to great community members. Namely, Harold “Duffy” Gaier and his son, Jeff, in Marshfield; Dick Hanusa (my Designated Pilot Examiner) in Oshkosh, John Chmiel from Wausau; Steve Krog in Hartford; and even down to John’s students Kathleen, Phil, Jim, Alana, and Tim. At the end of the day, a flight plan is a flight plan, altitude is altitude, and charts are charts, no matter where you are. Any experienced pilots know that SOPs, checklists, and performance numbers are based upon certain figures and data points. You could be in Alaska, Wisconsin, or Mauritius and you’d be using the same basic principles of flight. That can’t be said about the people in aviation. Each area has its own unique and rich aviation history. In Wisconsin, this culture is vibrant and thriving, Photos courtesy Chris Palmer

GUEST AUTHOR offering an incredibly hospitable environment to chase the dream of flight, whether that’s as a student or an instructor. From the iconic grounds of AirVenture, the ‘dots’ at Wittman Regional Airport, the gliders and Cubs at Hartford, Orange Roughy in Wausau, the Spruce Goose lumber of Marshfield, and the endless grass runways across the state, I only got but a taste of the Wisconsin aviation culture. One afternoon of study I found myself underneath the Spirit of St. Louis display in the EAA Museum. As I pondered my future as an instructor, inspiration coursed through my body, sometimes even standing the hair up on the back of my neck. And for the people that made it happen: John and Rose Dorcey, Dick Hanusa, and the many in between, I couldn’t ask for a better experience. A bit of my aviation heart now beats for Clockwise from top left: The top of Grewingk Glacier in Kachemak Bay. “I'm always cautious when I fly up these glacier valleys, but wow, what views!” says Chris. Chris flew with John and his student, Kathleen, to observe and learn teaching techniques. Another momentous occasion: first dual given. Says Chris, “It’s great to be instructing immediately.” It’s not uncommon to see a DeHavilland Beaver, on many Alaskan lakes. This one operated by Emerald Air in Homer, Alaska. Planes on a beach, not something we typically see in Wisconsin. Wisconsin. It beats amongst the peaks of snow, the lush-green coastline, the grizzly bears, the bush-wheels, and the many students I’ll teach in Alaska. The knowledge, experiences, and skill I gained from the great people and places of Wisconsin will now forever be a part of the aviation culture in Alaska. About the author: Chris Palmer is a flight instructor who lives in Homer, Alaska, with his wife and son. He owns Angle of Attack, producing flight training media, video and online learning. Chris produces AviatorCast podcast and the Angle of Attack videos on YouTube. 9 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

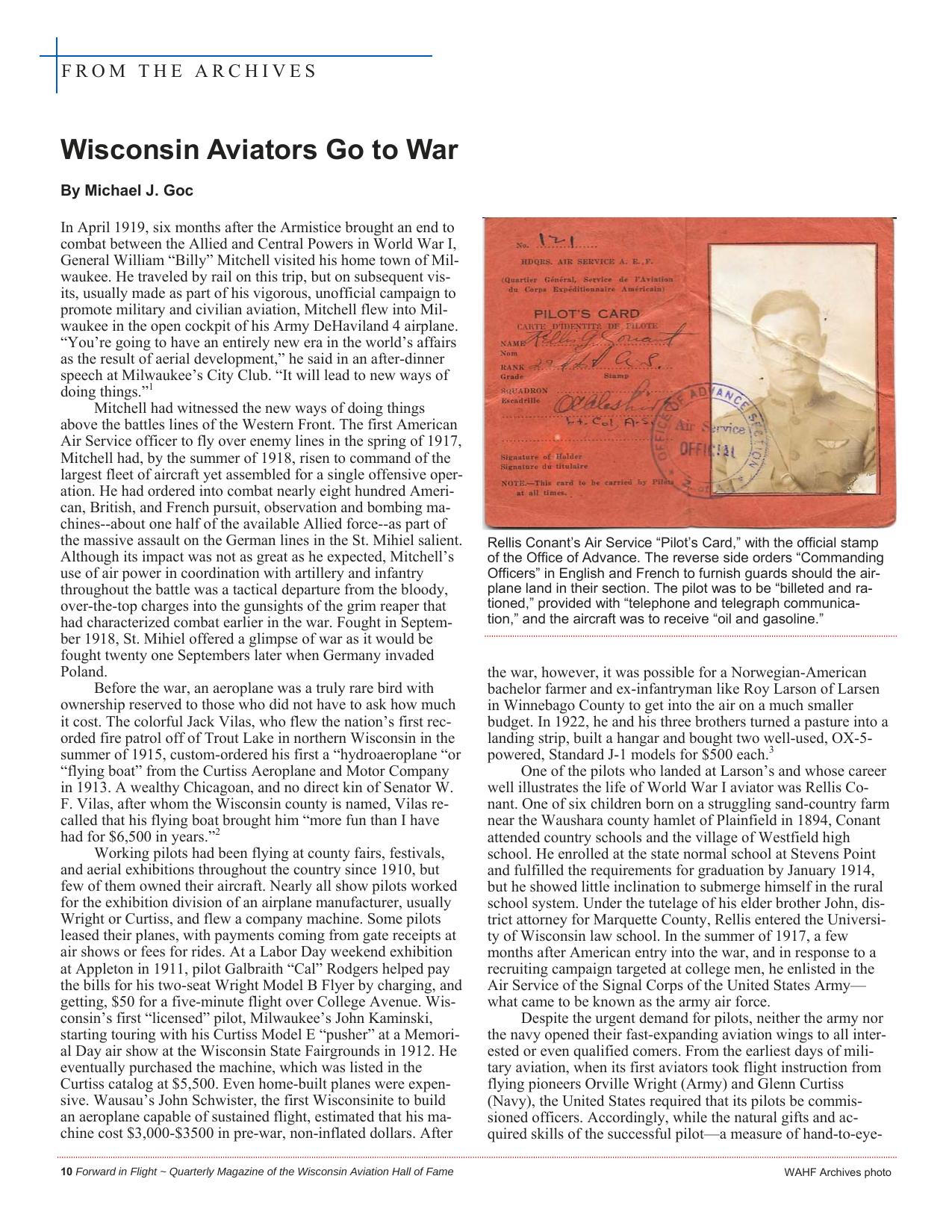

FROM THE ARCHIVES Wisconsin Aviators Go to War By Michael J. Goc In April 1919, six months after the Armistice brought an end to combat between the Allied and Central Powers in World War I, General William “Billy” Mitchell visited his home town of Milwaukee. He traveled by rail on this trip, but on subsequent visits, usually made as part of his vigorous, unofficial campaign to promote military and civilian aviation, Mitchell flew into Milwaukee in the open cockpit of his Army DeHaviland 4 airplane. “You’re going to have an entirely new era in the world’s affairs as the result of aerial development,” he said in an after-dinner speech at Milwaukee’s City Club. “It will lead to new ways of doing things.”1 Mitchell had witnessed the new ways of doing things above the battles lines of the Western Front. The first American Air Service officer to fly over enemy lines in the spring of 1917, Mitchell had, by the summer of 1918, risen to command of the largest fleet of aircraft yet assembled for a single offensive operation. He had ordered into combat nearly eight hundred American, British, and French pursuit, observation and bombing machines--about one half of the available Allied force--as part of the massive assault on the German lines in the St. Mihiel salient. Although its impact was not as great as he expected, Mitchell’s use of air power in coordination with artillery and infantry throughout the battle was a tactical departure from the bloody, over-the-top charges into the gunsights of the grim reaper that had characterized combat earlier in the war. Fought in September 1918, St. Mihiel offered a glimpse of war as it would be fought twenty one Septembers later when Germany invaded Poland. Before the war, an aeroplane was a truly rare bird with ownership reserved to those who did not have to ask how much it cost. The colorful Jack Vilas, who flew the nation’s first recorded fire patrol off of Trout Lake in northern Wisconsin in the summer of 1915, custom-ordered his first a “hydroaeroplane “or “flying boat” from the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company in 1913. A wealthy Chicagoan, and no direct kin of Senator W. F. Vilas, after whom the Wisconsin county is named, Vilas recalled that his flying boat brought him “more fun than I have had for $6,500 in years.”2 Working pilots had been flying at county fairs, festivals, and aerial exhibitions throughout the country since 1910, but few of them owned their aircraft. Nearly all show pilots worked for the exhibition division of an airplane manufacturer, usually Wright or Curtiss, and flew a company machine. Some pilots leased their planes, with payments coming from gate receipts at air shows or fees for rides. At a Labor Day weekend exhibition at Appleton in 1911, pilot Galbraith “Cal” Rodgers helped pay the bills for his two-seat Wright Model B Flyer by charging, and getting, $50 for a five-minute flight over College Avenue. Wisconsin’s first “licensed” pilot, Milwaukee’s John Kaminski, starting touring with his Curtiss Model E “pusher” at a Memorial Day air show at the Wisconsin State Fairgrounds in 1912. He eventually purchased the machine, which was listed in the Curtiss catalog at $5,500. Even home-built planes were expensive. Wausau’s John Schwister, the first Wisconsinite to build an aeroplane capable of sustained flight, estimated that his machine cost $3,000-$3500 in pre-war, non-inflated dollars. After 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Rellis Conant’s Air Service “Pilot’s Card,” with the official stamp of the Office of Advance. The reverse side orders “Commanding Officers” in English and French to furnish guards should the airplane land in their section. The pilot was to be “billeted and rationed,” provided with “telephone and telegraph communication,” and the aircraft was to receive “oil and gasoline.” the war, however, it was possible for a Norwegian-American bachelor farmer and ex-infantryman like Roy Larson of Larsen in Winnebago County to get into the air on a much smaller budget. In 1922, he and his three brothers turned a pasture into a landing strip, built a hangar and bought two well-used, OX-5powered, Standard J-1 models for $500 each.3 One of the pilots who landed at Larson’s and whose career well illustrates the life of World War I aviator was Rellis Conant. One of six children born on a struggling sand-country farm near the Waushara county hamlet of Plainfield in 1894, Conant attended country schools and the village of Westfield high school. He enrolled at the state normal school at Stevens Point and fulfilled the requirements for graduation by January 1914, but he showed little inclination to submerge himself in the rural school system. Under the tutelage of his elder brother John, district attorney for Marquette County, Rellis entered the University of Wisconsin law school. In the summer of 1917, a few months after American entry into the war, and in response to a recruiting campaign targeted at college men, he enlisted in the Air Service of the Signal Corps of the United States Army— what came to be known as the army air force. Despite the urgent demand for pilots, neither the army nor the navy opened their fast-expanding aviation wings to all interested or even qualified comers. From the earliest days of military aviation, when its first aviators took flight instruction from flying pioneers Orville Wright (Army) and Glenn Curtiss (Navy), the United States required that its pilots be commissioned officers. Accordingly, while the natural gifts and acquired skills of the successful pilot—a measure of hand-to-eyeWAHF Archives photo

FROM THE ARCHIVES coordination, reasonably quick reflexes, a basic understanding of aerial navigation, all leavened by a generous measure of common sense and good luck—were not necessarily conferred with a sheepskin, America’s institutions of higher learning sent their men to war in the air. Brown University sent Janesville native George Parker into naval aviation, where he flew an improved model of the Vilas/ Curtiss flying boat at the new naval air station at Pensacola, Florida. Carroll College, Waukesha, sent Rodney Williams, who trained with the Royal Flying Corps in Canada and Britain, then with the American 17th Aero Squadron in France. Flying a British-made Sopwith Camel “pursuit” aeroplane in the summer and fall of 1918, Williams downed four enemy aeroplanes and one balloon to become Wisconsin’s first and its only World War I “ace.”4 Among the many University of Wisconsin aviators was Paton McGilvary who, upon completing his Air Service training, become one of a few hundred Americans assigned to the Italian air force. McGilvary piloted lumbering and gigantic—for their day—Caproni open-cockpit bombers on harrowing night time raids on Austrian forces occupying the Croatian coast of the Adriatic and the foothills of the Italian Alps. Paul Meyers was another Madison graduate. Star of Badger football and basketball in 1916, fraternity brother and allaround BMOC, Meyers had the look and credentials of a pulp fiction knight of the air—and lived up to the image. Assigned to the First Aero Squadron under the command of Billy Mitchell, Meyers piloted a speedy, French-built Salmson observation machine. On one mission, he flew a solo airplane, daylight, lowaltitude reconnaissance run over enemy lines. Hugging the ground, never higher than 1,000 feet, Meyers and his observer were targets not just for anti-aircraft guns, but for every machine -gun, rifle, and rock thrower in the trenches. With help from the Salmson, which could reach speeds more than 125 MPH, Meyers survived a continuous barrage of fire, completed his mission, and received the Croix de Guerre for his efforts.5 Although he was a country boy who earned his degree within the rustic confines of Stevens Point Normal, Rellis Conant fit the popular mold of a World War I aviator. Taller than average, blonde and athletic, Conant was fearless, charming, gregarious, the kind of man who could talk his way into and then charm his way out of any scrape. Given the choice in the bellicose summer of 1917 between coming home to practice law with his elder brother in sleepy Westfield, Wisconsin, or going off to war as an Army pilot, Conant went off to war. He made his way to Texas where, according to family lore, he told Air Service induction officers swamped with applications from flyboy wannabes that he already was a pilot. When his bluff was called, Conant climbed into an aeroplane and took off. “It wasn’t so bad getting the plane off the ground that first time, but I didn’t know what was going to happen when I had to land.” Conant survived the escapade, which may have been more the stuff of legend than of fact. Even so, the brag was indicative of the man, who if not a born pilot, became one in short time. “When I was a boy back home I was afraid to climb high and never wanted to oil the windmill, no matter how much it squeaked. But when I got started in aviation work, I liked it.”6 He got started in the work he liked in ground school at the University of Texas at Austin, then at Ellington Field near San Antonio. Ellington was one of a dozen army landing strips freshly scraped out of the warm and dusty flatlands of Texas and USAF Museum Photo A Curtiss JN-4, the airplane that trained virtually all Air Service pilots in World War I. where many airmen from the Midwest trained. Hastily equipped with tents for barracks and board sheds identified as “hangars” even though they now sheltered aeroplanes instead of balloons, Ellington and other Texas air fields introduced aspiring air warriors from both the United States and Canada, if not to aerial combat, at least to the air. The introduction almost always took place in the front cockpit of a JN-model training aircraft. Conceived in 1914, when Glenn Curtiss, in need of a successful tractor aeroplane to replace his earlier pusher machines, combined a Model J aircraft designed by Douglas Morse with his own Model N machine. In no time, the JN became the “Jennie,” affectionately, and sometimes not so affectionately, remembered as a new flyboy’s first date in the air. The original model JN underwent many design and engine modifications, both in the Curtiss plant prior to American entry in the war and at Curtiss and the other plants licensed to produce the planes after the U.S. joined the Allies. Military model numbers started with the JN-2 and JN-3, which carried the army’s first air warriors into action during the Mexican border intervention of 1916, and ended many models down the line with the JN6HP of late 1918. More JN-4Ds were built than any other model and, powered by the 90-HP, V-8, OX-5 engine, were flown in training by more Army and Navy pilots than any other machines. “It was a thrilling experience I can tell you,” wrote Wausau Air Cadet Paul Tobey of his first solo flight. “The first trip around wasn’t very exciting, except as the radiator sent a stream of water back onto my face and goggles that I couldn’t see.” The Texas heat seared OX-5 cooling systems while the dust raised by hundreds of machines buzzing on and over bare earth landing strips so pitted wooden propeller blades that they had to be replaced after only a few flights. Accidents were common and often fatal. As Tobey recalled, “My first landing was about as bad as a landing can be without breaking anything, which means that it wasn’t so bad after all.”7 Before an air cadet could make or break anything on his first landing, he attended ground school. If he could pass a written exam with questions on general math, airplane construction, map reading and the dropping of bombs from an open cockpit, he proceeded to forty hours flight training in a JN. After a few 11 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

FROM THE ARCHIVES months, which saw the flight-training program punctuated by a troubling tattoo of ground loops, nose flips, landing gear smashed and other frequently fatal mishaps, the Army increased flight training time. By the end of the war, the Air Service concluded that it would take ninety hours of training in the cockpit before a pilot was ready to test for his commission as a Military Aviator. The test began with the cadet ordered to take off, fly to an altitude of 3,000 feet, descend and land in one piece. Next he was required to fly to 1,500 feet, cut off the engine, and “volplane” or glide to a safe landing within 300 feet of a designated spot. The cadet’s normal anxiety at switching off his engine was intensified by the OX-5’s patent reluctance to restart without “propping,” which required a second person and the plane to be on the ground. When he cut off the power at 3,000 feet the aspiring Military Aviator was left with two choices: glide to a safe landing, or crash. He could take comfort in the knowledge that the JN, which weighed about 1400 pounds (plus pilot) volplaned well and, depending on the whims of the wind and the unpredictable air traffic generated by novice pilots careening over the training field, could usually be landed safely and on target. Perhaps the most challenging test required the cadet to complete a 100-mile flight over a triangular course, make two safe landings and take offs, then return to base within 48 hours. Since the JN had a top speed of about 75 MPH and carried enough fuel to fly two-hundred-fifty air miles, a one-hundredmile round trip in two days time would seem to be a small challenge. However, finding a strange landing field, even in the flat, unpopulated stretches of south Texas, was not easy for an inexperienced pilot whose store of navigational aids consisted of a pocket compass, a ground school course in how to “read” the terrain and a railroad map flapping in the breeze of the open cockpit. In all, about one in five cadets failed the flight test and did not qualify as commissioned Military Aviators.8 Not that a commission guaranteed competence. In May 1918, the Post Office and the Army made a highly-publicized inaugural of “air mail” service from Washington D.C. to New York City via Philadelphia. With a grassy stretch of the Capitol Mall drafted for a landing strip and a crowd of well-wishers to cheer him on, the newly commissioned Military Aviator assigned to make the first flight shook hands with President Woodrow Wilson, climbed into the cockpit of his modified-for- mail JN4H, roared past the Washington Monument, circled the Capitol Dome, and followed the railroad line to... Richmond, Virginia. After two hours in search of Philadelphia, which should have been a forty-minute flight north, and with his fuel running low, the hapless Aviator then cracked up his plane while making a forced landing in a Virginia farm field, approximately 180 degrees off course.9 While the New York mail was lost over Virginia, Rellis Conant was on his way to the optimistically-named Zone of Advance in Europe. He had passed his flight test in February 1918, obtained his commission and was assigned to flight instruction duties in Texas. In July, he boarded ship for England where he joined the 168th Observation Squadron. Scheduled to embark for England on the ill-fated troopship Tuscania in December 1917, the 168th had been bumped, perhaps mistakenly, by the 158th Squadron, which suffered heavy losses when the Tuscania was torpedoed and sunk. Spared the fate of its brother squadron, the lucky 168th arrived in England in January 1918 under orders to spend five months training in French and British combat machines. In fact, the 168th spent more than five months waiting for aircraft of any kind. Not until October, after Conant had arrived as a replacement pilot, did the 168th reach France and receive the first consignment of planes it could call its own. Upon entering the war, military preference, business interest and political sentiment in the United States called for the construction of American planes powered by American engines and flown in combat by American pilots. Considering the all but virtual state of the American aircraft industry in the spring of 1917, and the war-driven progress European aeroplane builders were making, just about any machine the U.S. could manufacture was certain to be inferior before it rolled off the assembly line. By comparison, the war had so energized French aircraft builders that they could roll out a new model SPAD aeroplane, with combat-inspired alterations, in little more than thirty days. Consequently, the Americans agreed to concentrate on producing the training planes and engines--chiefly JNs, OX-5s and Liberties—they already knew how to build, while using British, French and Italian planes at the Front. Hence, Rodney Williams flew a Sopwith, Paul Meyers a Salmson, Paton MacGilvary a Caproni, and nearly all the aircraft Billy Mitchell commanded at St. Mihiel were European machines. The first product of the American aviation industry to Above: A SPAD VII fighter, of the type flown by Rodney Williams, on display at the USAF Museum. Right: A DeHaviland on display at the USAF Museum with a fueling wagon nearby. Critics dubbed the plane “the flying coffin” because the fuel tank was located in between the cockpits. 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Photos courtesy USAF Air Force Museum

FROM THE ARCHIVES Workers at the Wright factory in Dayton used the fuselage of this DeHaviland 4 to announce it was their 1000 plane headed for Europe. reach the Zone of Advance was the DH-4, a reworked version of a 1916 British DeHaviland observation plane improved by the addition of the new 400 horsepower Liberty engine. The twelvecylinder Liberty could pull a fully-loaded 3500-pound DH-4 at about 120 MPH, with only a little help from a tailwind. Armed with two-forward facing machine guns fired by the pilot and two pivoting guns manned by the observer in the rear cockpit, the DH-4 was well equipped, if not for pursuit, at least to defend itself. Early models of the plane, which caught up with American air men in Europe in August 1918, featured a 66-gallon fuel tank crammed into the space between the pilot and the observer. On an aeroplane made of wood strips, resin and cloth, and fired on by modern machine guns and artillery, no place could be called safe for sixty-six gallons of highly-flammable gasoline. Nonetheless, after a few fiery, fatal crashes, the proximity between its crew and fuel tank earned for the DeHaviland the grim nickname of “Flaming Coffin.” Its unfortunate reputation clung to the DH-4, even though Army analysts found it to be no more lethal to those who flew it than any other observation plane used in what was, after all, a war.10 The 168th Observation Squadron received its new DeHavilands in mid-October 1918. It was one of eight Air Service observation and bombing squadrons to fly the American-built plane. Of the other twenty-four Yankee Squadrons on the Western Front on November 1, twenty-three flew French machines, and one sent up British planes. On November 5, Lieutenant Rellis Conant, pilot, with Lieutenant Colonel John Curry in the observer’s seat, took off from the main Allied airdrome at Toul on a routine reconnaissance patrol over the lines. They sighted an enemy observation balloon and—with typical Conant bravado—decided to attack. An observation balloon was a 100-plus foot long fabric bag tethered to the ground and filled with thousands of cubic feet of highly flammable gas. It might appear to be as easy to flatten as the plump caterpillar it resembled, but a “gasbag” was a difficult and dangerous target. The spotter riding in the gondola beneath the bag had a 360-degree field of vision and could detect enemy aircraft in time to order a descent and alert the ring of anti-aircraft guns and pursuit planes that were part of the balloon deployment. The balloon itself was kited up no more than 800 feet above ground, which meant that an attacking aeroplane had to fly through a long barrage of anti-aircraft fire on the way in and out. Some balloons also carried suicide packages in the form of a gondola stuffed with explosives. Flames from the burning gas or the attacker’s own bullets could set off the explosives which could damage the aeroplane or blast it entirely out of the sky. For a combat rookie to successfully attack a balloon while on a scouting flight in a slow-moving observation plane was the equivalent of a baseball player slamming the ball out of the park on his first time at bat in the major leagues. Unlikely but possible, and that is what Rellis Conant did on November 5, 1918, when he put his DH-4 into a flight school dive with forward guns blazing and shot a balloon out of the sky.11 Conant was part of an observation squadron whose job was reconnaissance and not pursuit or bombing, but he did find himself under fire several times in the final week of the war. “The most thrilling experience I had was when my observer was shot through the head. On that flight, my machine was pierced with fifteen bullets, one of them coming within two inches of my own head. I have had two planes so damaged by shell fire they had to be abandoned.”12 In postwar press reports, Conant was touted as having shot down two enemy aircraft and one balloon, but the Army officially credited him with only the balloon victory. Confirming a victory, which required a written statement from an eyewitness, was not always easy and many pilots could honestly claim a ranking higher than that reported on the official list--should they want one, and most of them did. Death was mass produced in World War I, anonymous artillery and machinegun fire were the leading slayers of men in combat, yet the custom of counting and publicizing individual victories was popular among most pilots and all propagandists. The knight on horseback had been replaced by the knight of the air, at least in the pages of the woodpulp press.13 Conant might have claimed more victories, or he might have been shot out of the sky, had he been able to spend more time in the air. He logged twelve hours and eighteen minutes of flight time in the Zone of Advance. It was a typically brief front line career for an American aviator. By the time most Air Service pilots were adequately trained, supplied with aeroplanes and transported to the Front, the war was all but over. So it was for Rellis Conant, who did nearly all of his combat zone flying in the final week of the war. A swift stand-down of American air forces followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918. By May 1919, the U.S. Army, which had over 4,000 pilots ready to fly at the end of the war, discharged more than 3,000 of them. Orders for aeroplanes and other aviation equipment were cancelled, machines already delivered to Europe destroyed and completed aircraft sold below cost. The war was over and, as announced by Billy Mitchell, the new age of aerial development began. Advances on the military front were readily transferable to the civilian realm. In its nineteen months at war, the United States had created an aviation industry which manufactured approximately 12,000 “aeroplanes.” In 1916, by comparison, American aircraft production totaled about 400 flying machines. The war also stimulated production of the OX-5 aircraft engine and spurred development of the more powerful Liberty 12 mo13 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

FROM THE ARCHIVES tor. Dependable, relatively easy to maintain, and plentiful after the war, the OX-5, the Liberty 12, and their design descendants were the work horse power plants of American aviation until the mid-1920s.14 At war’s end, a majority of these planes and engines resided in hangars, warehouses and factories in the United States, Canada and Europe. Many were well-worn training machines, but just as many more had flown only a few hours or had yet to emerge from their shipping crates. Declared surplus property by Britain, France, Canada and the United States, they entered the civilian market at discount prices. An in-the-crate Curtiss JN-4D aeroplane and a spanking-new OX-5 engine, which cost the United States government at least $5,500 during the war, were advertised for less than $3,000 in 1919. Used machines and, as time passed, all machines, could be had for much less. By 1922, a rebuilt OX-5-powered “Canuck” or Canadian-built Curtiss JN, could be purchased in Wisconsin for $500-$600.15 The war also supplied people to buy and fly these aeroplanes. Nearly 220,000 men had served in the United States Army Air Service, in the U. S. Naval Flying Corps and with Allied units such as France’s famed Lafayette Flying Corps. They formed a cadre of trained ground crew and pilots thrust by peace into a civilian economy with little awareness of, let alone need, for their skills. In addition, for every man in the air above the trenches, there seemed to be at least one in the trenches, and many more who had experienced the war in the air via juiced-up news articles, novels and moving pictures, who vowed to take up flying at war’s end. Indeed, the story of aviation in the years after World War I is one of pilots, engineers, manufacturers, marketers, bureaucrats, insightful dreamers, and on-the-fringe crackpots searching for ways to make a living in the air. These men and women would democratize aviation in the United States in the years immediately after the war and bring it to a welcoming public eager to experience it. Editor’s Note An expanded version of this article appeared in the Autumn, 2001 issued of the Wisconsin Magazine of History. Of the aviators mentioned here, Billy Mitchell, Jack Vilas, John Kaminski, John Schwister, Roy Larson, Paul Culver, Rodney Williams, and Rellis Conant have been inducted into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. Annotations: 1 Milwaukee Sentinel, April 23, 1919. 2 Aero and Hydro, June 21, 1913. 3 Cal Rodgers Appleton flights reported in Appleton Post, September 2 & 5, 1911. A few months later Rodgers, flying a Wright Model B named the Vin Fiz, after the soda pop brand underwriting it, made the first coast-to-coast aeroplane flight across the United States. John Kaminski earned license No. 121 as issued by the Aero Club of America and le Federation International Aeronautique in 1912. The United States government did not license pilots until 1926. Kaminski Papers, Archives, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. John Schwister flew Wisconsin's first home-built airplane capable of sustained flight in June 1911. Wausau Daily-Record Herald, June 23, 1911. 4 Parker family history scrapbook, courtesy Geoffrey Parker. Rodney William's combat record in U.S. Air Service Victory Credits, USAF Historical Study No. 133. 5 McGilvary in Fitch, Wings in the Night, 100-103; Meyers in Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 145 and Liberty Badger, v. 34., p. 389. 6 It is highly unlikely that anyone without any training or experience could fly an airplane, but the story has been handed down in the family and was told by Bruce Hamilton to Fran Sprain, Marquette County Tribune, May 22, 1986; Conant quoted in Milwaukee Journal, January 15, 1919. 7 Paul Tobey letter in "Wahiscan" Annual of Wausau High School, 1918. 8 Requirements for Military Aviator, Circular 10, Chief Signal Officer of the War Department, October 27, 1913. 9 Waiting in Philadelphia to carry the mail to New York was Eau Claire native and Air Service Lieutenant Paul Culver. The air mail service overcame its first day jinx and continued reliably for about four months until the experiment was halted. Culver, The Day the Air Mail Began, pps. 34-59 and Lipsner, The Airmail, Jennies to Jets, pps. 4-24. 10 Wagner, American Combat Planes, pps.31-32. The Air Service ended the war with several thousand surplus DH-4's which performed reliably for the army and the air mail service. 11 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 358. 12 Milwaukee Journal, January 15, 1919. 13 Among the many volumes entitled Knights of the Air was that penned by one-time Wausau resident Bennett Molter, who joined the Lafayette Flying Corps by way of Hollywood in 1916, returned to the U.S. and penned his paean to "American boys" of whom too much could hardly be said." for the War Department in August 1918. 14 By November 1918, the United States was producing aircraft at the rate of 23,000 planes a year. Gorrell, The Measure of America's World War Aeronautical Effort, p. 34. To power those planes, American manufacturers, led by the Lincoln, Packard and Ford Motor companies produced nearly 30,000 engines. Gorrell, p. 70. 15 The cost charged to the U.S. government for military aircraft found in Lincke, Jenny Was No Lady, p.97; postwar sales prices as advertized in Aerial Age Magazine, October 13-20, 1919; cost of Canucks in 1922 recalled by Bruce Hamilton in videotaped interview with Jack Conant, October 1990. 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Photo courtesy of Rose Dorcey

Morey Airplane Company Since 1932 Middleton Municipal Airport/Morey Field Self-service 100LL & Jet A 24-7 15 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

WE FLY 100th Anniversary of World War I US Entry By John Dorcey There are two reasons the United States entered World War I, neither of which had anything to do with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of AustriaHungary. Hostilities, in what was called, among other monikers, “The Great War,” had begun July 28, 1914, nearly three years before the United States declared war on April 6, 1917. President Woodrow Wilson had pledged the country would remain neutral. In fact, the campaign slogan for his second term (1916) was “he kept us out of war”. Submarine Warfare US neutrality would be tested numerous times, first on January 28, 1915 when the merchant ship William P. Frye was sunk, the first hostile action against the United States. Germany apologized and assured President Wilson that no further attacks against US shipping would occur. Then on May 7, 1915 when the German submarine U-20 sank the British liner Lusitania killing 128 Americans among the 1,201 victims. Again, Wilson demanded an end to attacks against unarmed passenger and merchant ships. Public opinion began to shift against Germany and became greater still as continued submarine attacks killed increasingly more Americans. On January 31, 1917 Germany announced it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare on February 1, 1917 within their declared war zone around Britain, France, and the Mediterranean. In response, two days later, President Wilson broke diplomatic relations with Germany on February 3. Between February 3 and April 6 Germany sank nine American ships while another sank after running into a German mine. Zimmermann Telegram On January 16, 1917, Henrich von Eckhardt, German Ambassador to Mexico, received a coded telegram from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann. The message suggested the ambassador offer the Mexican government Arizona, New Mexico, and part of Texas in exchange for their assistance in defeating the Americans. British intelligence decrypted the message and advised Presi- dent Wilson on February 26. On March 1, the contents of the “Zimmermann Telegram” were made public. Declaration of War On April 2, during a joint session of Congress, Wilson delivered his “War Message to Congress”. Wilson said, in part, “With a profound sense of the solemn and even tragical character of the step I am taking and of the grave responsibilities which it involves, but in unhesitating obedience to what I deem my constitutional duty, I advise that the Congress declare the recent course of the Imperial German Government to be in fact nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States…” On April 4, the U.S. Senate voted 82 votes to 6 in favor of war; two days later, the House of Representatives delivered their affirmative vote 373 votes to 50, formally announcing the entrance of the United States into what would become the First World War. US Military Our military was unprepared for what it would be called to do. At the time war was declared, the Army consisted of approximately 200,000 troops, 80,000 of whom served in National Guard units. Congress enacted the Selective Service Act of 1917 late April and President Wilson signed it into law on May 18. By war’s end, more than 24 million men had registered for the draft. Nearly 2.8 million who served during World War I were drafted. The number of volunteer enlistments numbered slightly over 300,000. Then Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, reported “over 25 per cent of the entire male population of the country between the ages of 18 and 31 were in military service.” Members of the US armed forces during World War I totaled 4,734,991. The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) spent only 200 days in combat – from April 25, 1918 through November 11, 1918. Official Department of Defense figures for the period April 1, 1917 to December 31, 1918 include 116,708 deaths. Combat deaths were 53,402 or 45.8 percent of the total, non-combat 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame deaths totaled 63,114 or 54.2 percent. Another 204,002 were wounded. The above totals do not include the 757 merchant mariners that died during that period. According to the Wisconsin Veterans Museum nearly 120,000 of Wisconsin’s sons and daughters served in all branches of the US military during the war. They also report that more than 2,000 Wisconsinites died while in service to their country. That equates to a mortality rate 1.66 percent. US Air Service The first Air Service (AS) members (8 officers and 207 enlisted) arrived in England during July 1917. Not until April 1918 would significant numbers (40,000) of US Air Service members reach Europe. Air Service troops would total 79,980 at 1918 yearend. Air Service pilots flew 6,624 aircraft, 74 percent of which were manufactured in France. In addition to the 1,443 supplied by American aircraft manufacturers, England provided 283 aircraft and Italy 19. Other Volunteers Many adventure seeking, military-age men, didn’t wait for the United States to enter the war. Some went to Canada WAHF Archives photo

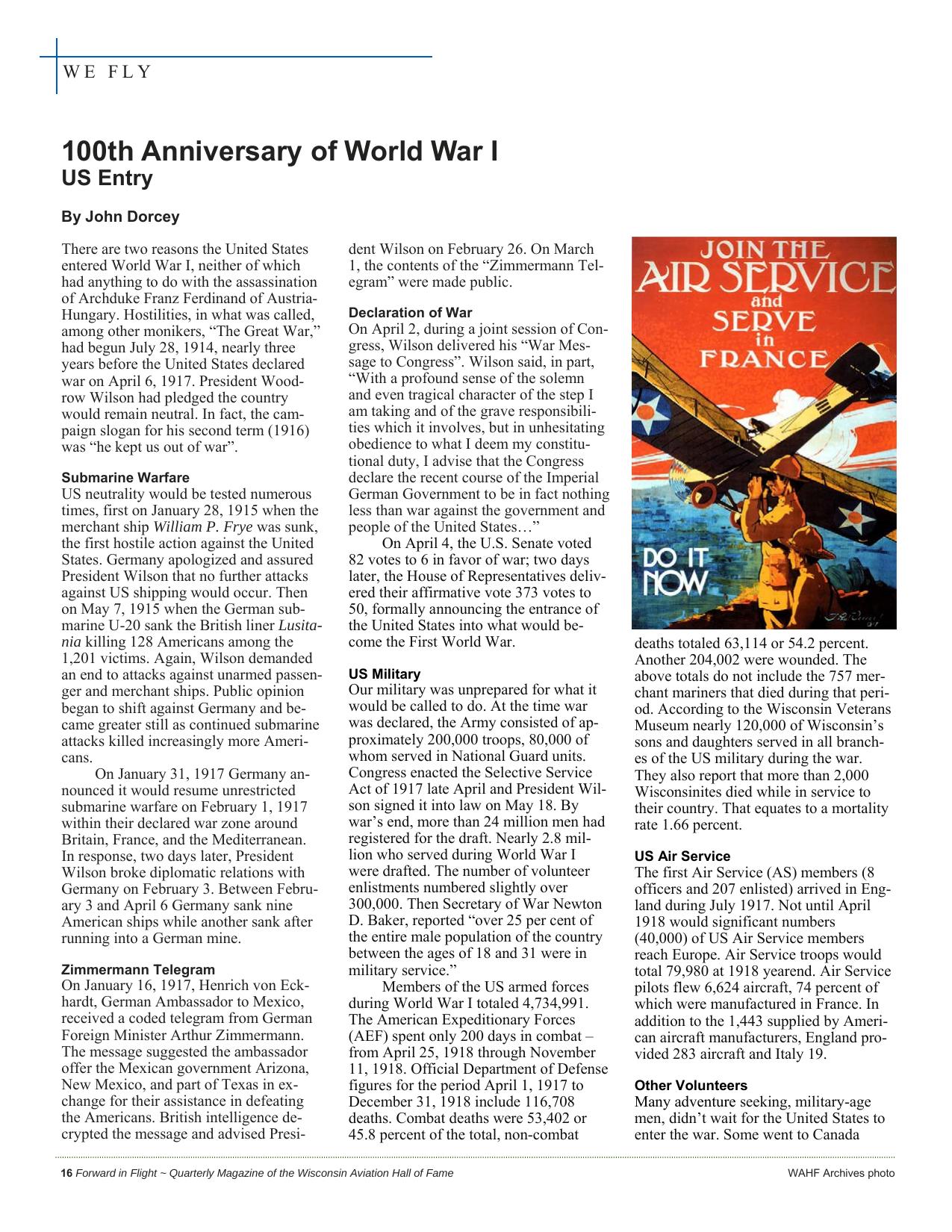

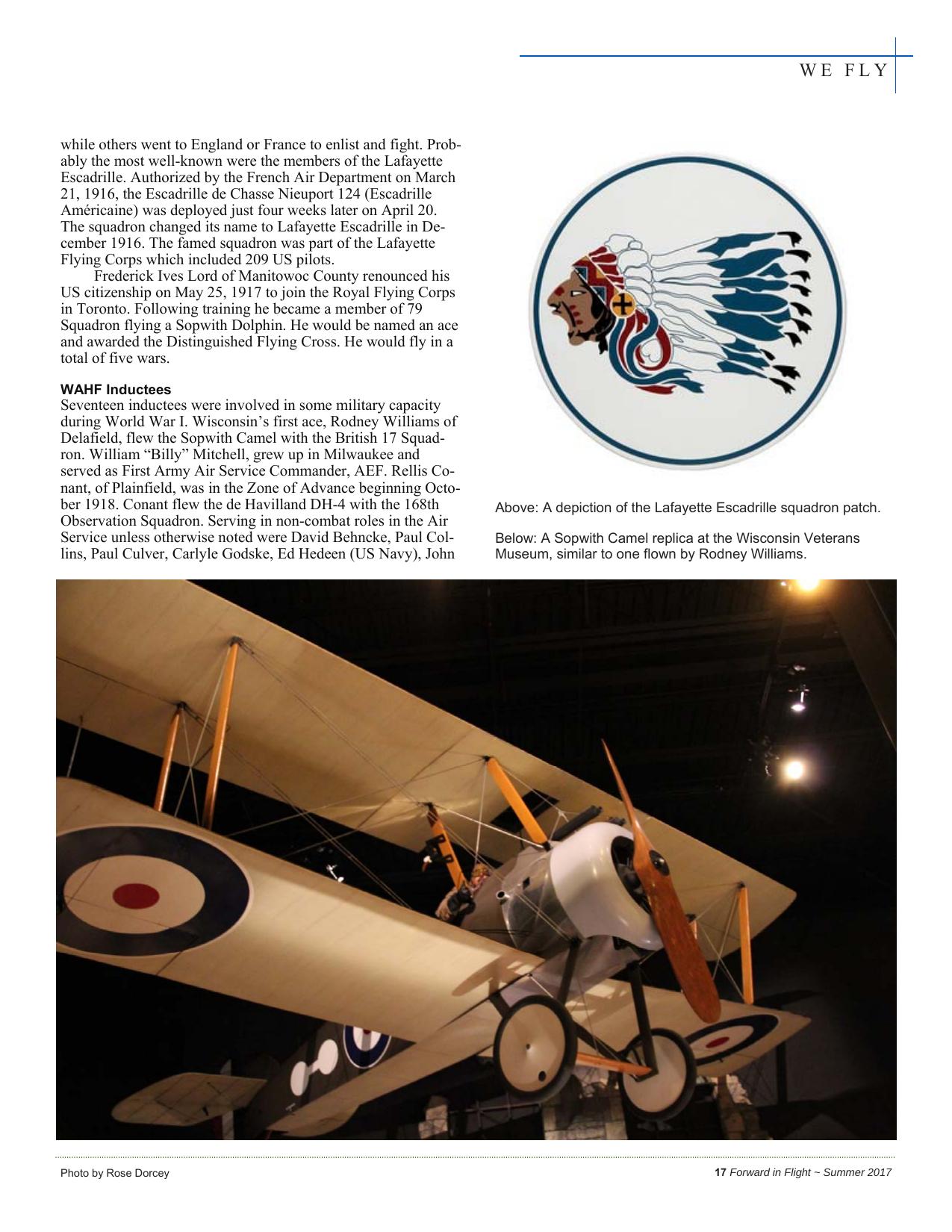

WE FLY while others went to England or France to enlist and fight. Probably the most well-known were the members of the Lafayette Escadrille. Authorized by the French Air Department on March 21, 1916, the Escadrille de Chasse Nieuport 124 (Escadrille Américaine) was deployed just four weeks later on April 20. The squadron changed its name to Lafayette Escadrille in December 1916. The famed squadron was part of the Lafayette Flying Corps which included 209 US pilots. Frederick Ives Lord of Manitowoc County renounced his US citizenship on May 25, 1917 to join the Royal Flying Corps in Toronto. Following training he became a member of 79 Squadron flying a Sopwith Dolphin. He would be named an ace and awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. He would fly in a total of five wars. WAHF Inductees Seventeen inductees were involved in some military capacity during World War I. Wisconsin’s first ace, Rodney Williams of Delafield, flew the Sopwith Camel with the British 17 Squadron. William “Billy” Mitchell, grew up in Milwaukee and served as First Army Air Service Commander, AEF. Rellis Conant, of Plainfield, was in the Zone of Advance beginning October 1918. Conant flew the de Havilland DH-4 with the 168th Observation Squadron. Serving in non-combat roles in the Air Service unless otherwise noted were David Behncke, Paul Collins, Paul Culver, Carlyle Godske, Ed Hedeen (US Navy), John Photo by Rose Dorcey Above: A depiction of the Lafayette Escadrille squadron patch. Below: A Sopwith Camel replica at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum, similar to one flown by Rodney Williams. 17 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2017

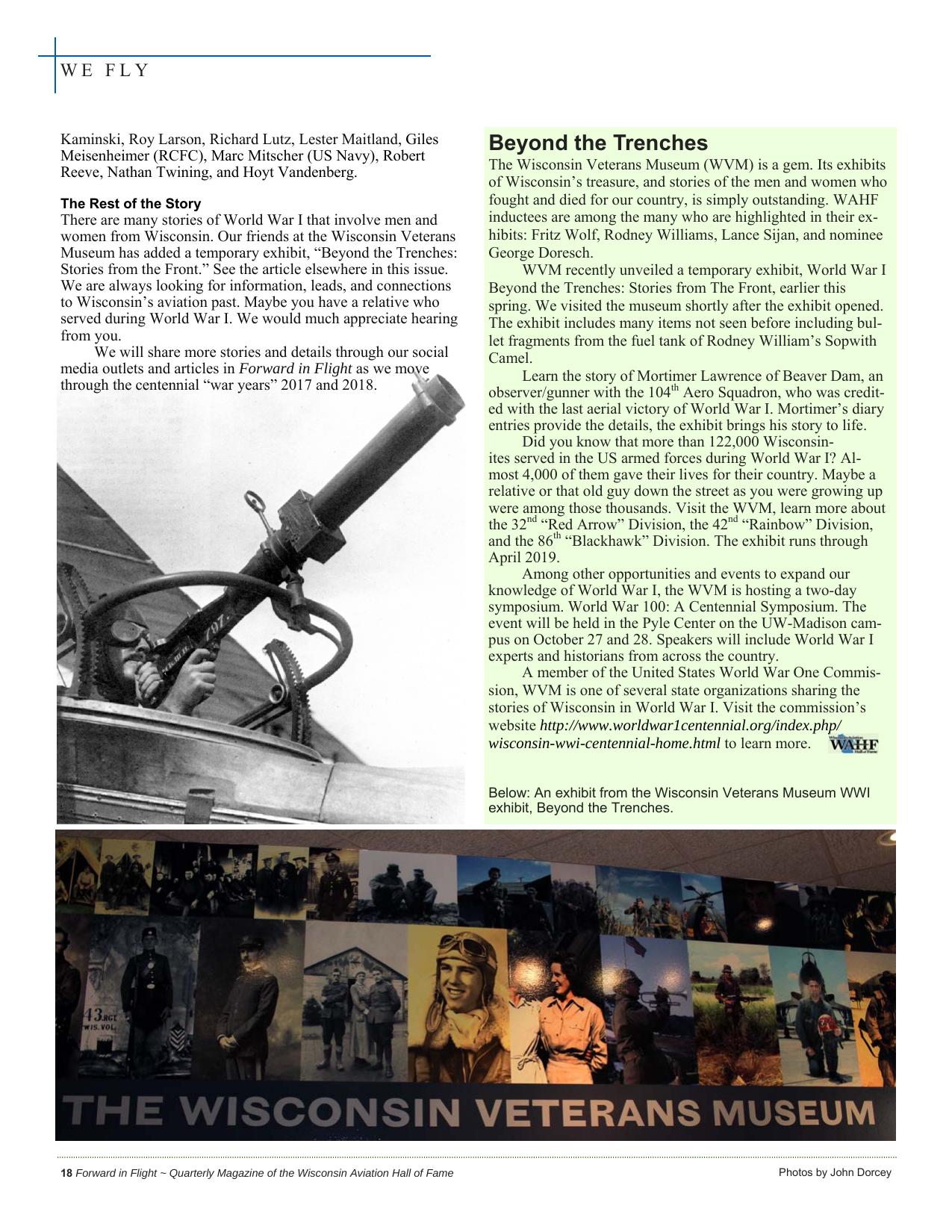

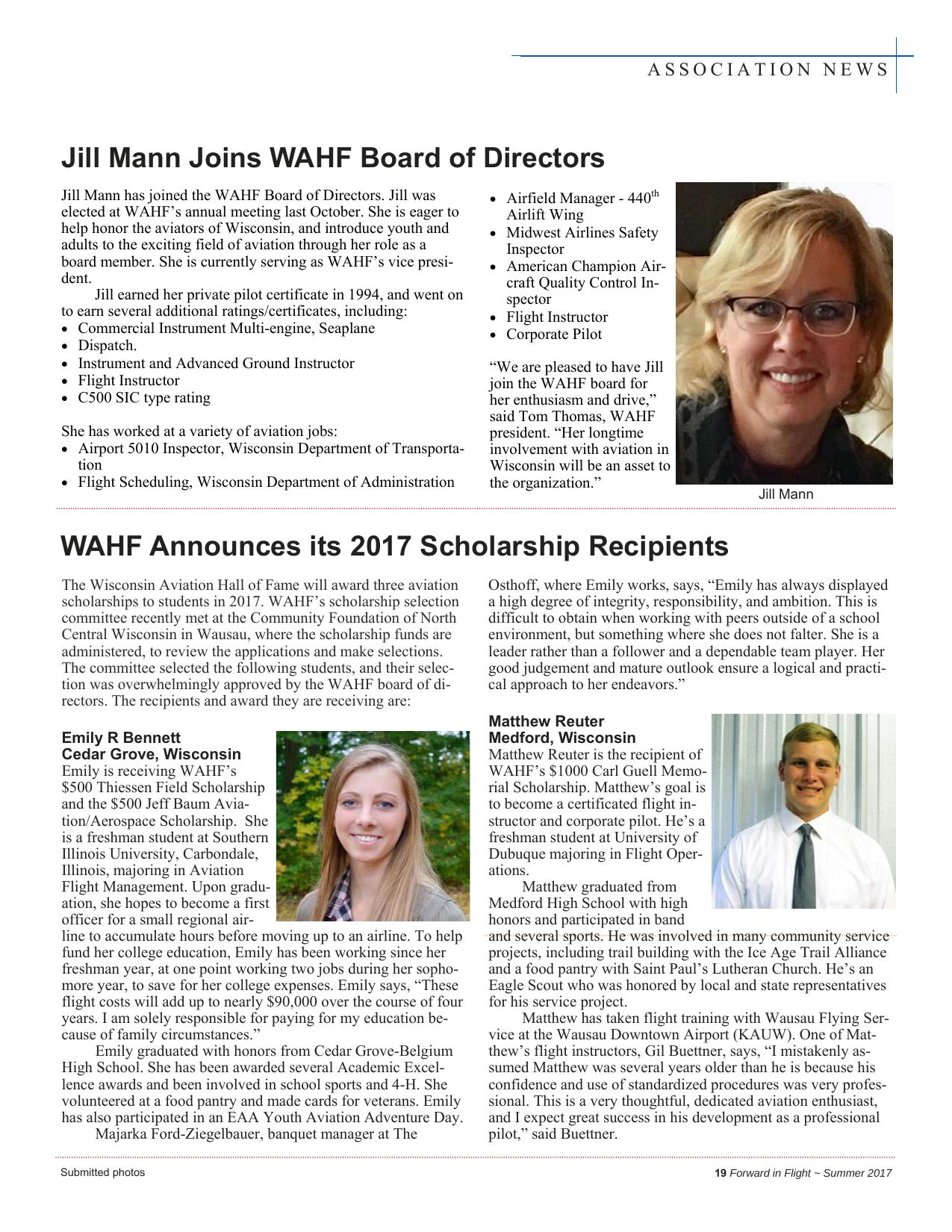

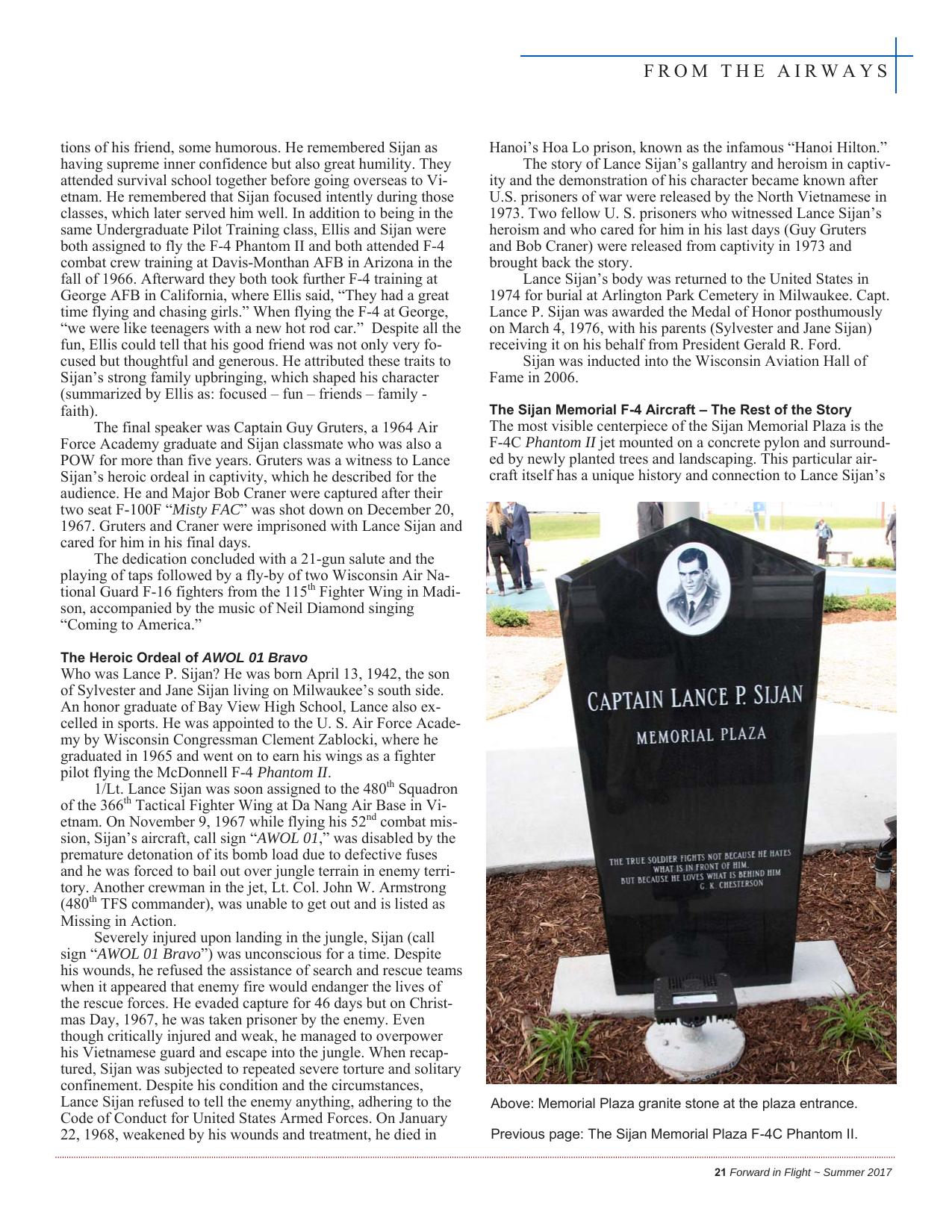

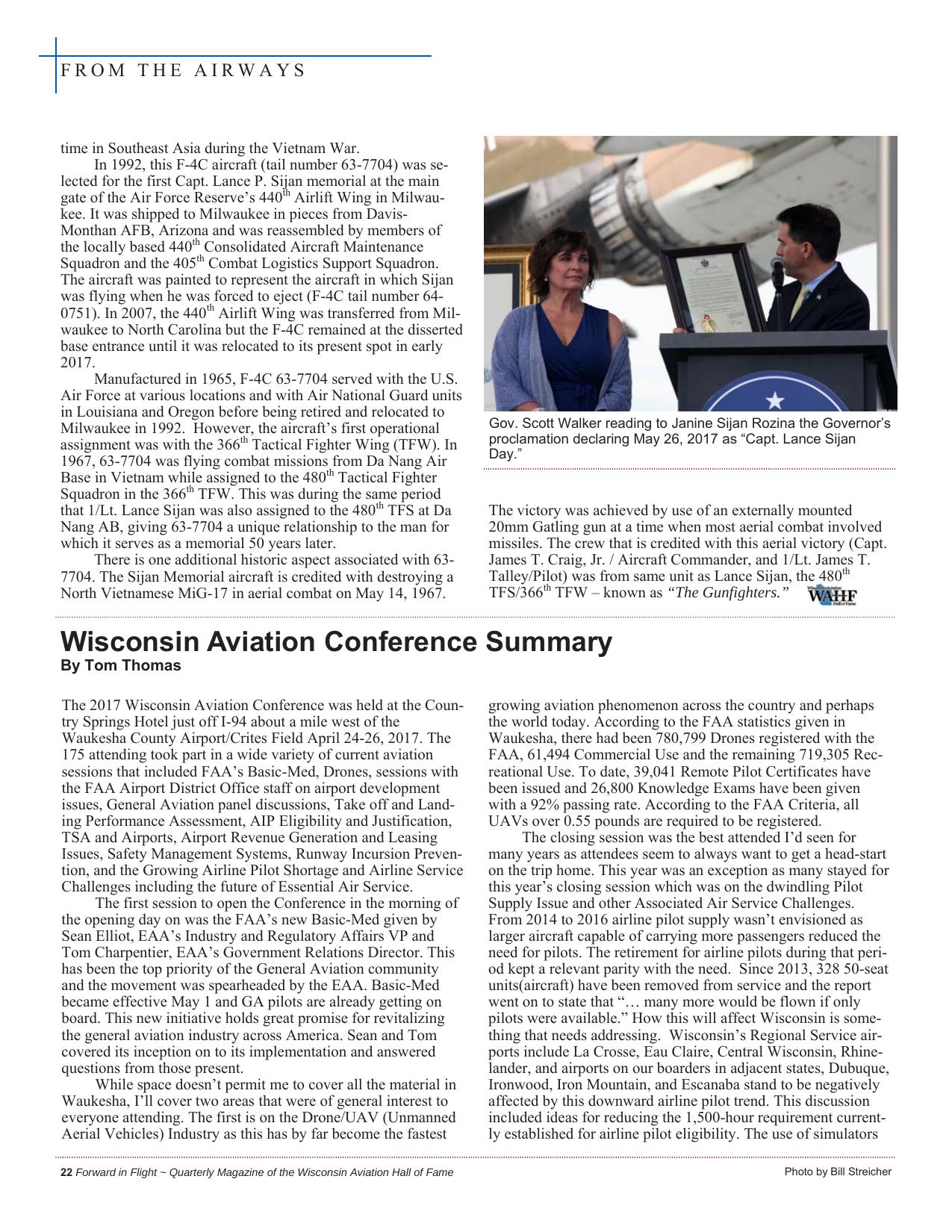

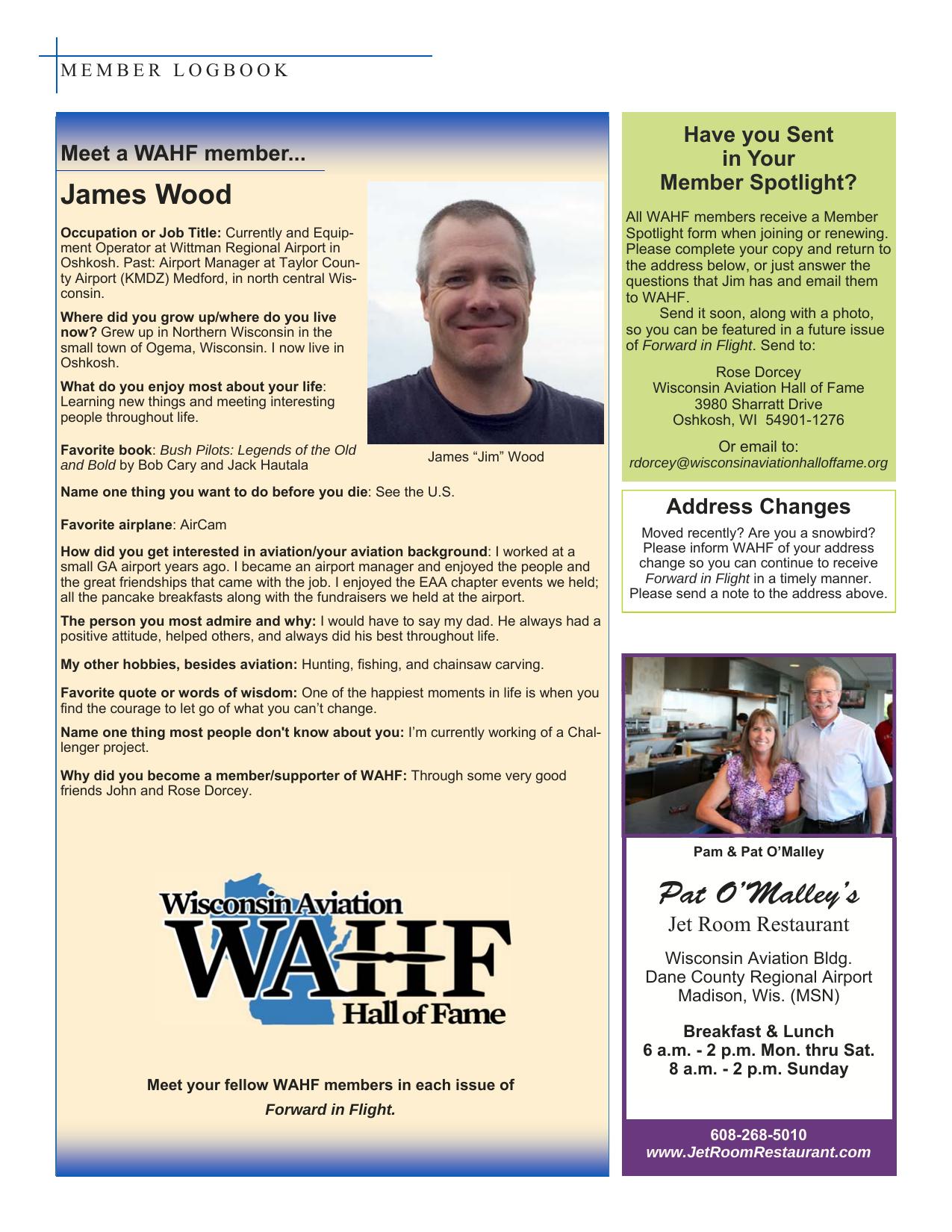

WE FLY Kaminski, Roy Larson, Richard Lutz, Lester Maitland, Giles Meisenheimer (RCFC), Marc Mitscher (US Navy), Robert Reeve, Nathan Twining, and Hoyt Vandenberg. The Rest of the Story There are many stories of World War I that involve men and women from Wisconsin. Our friends at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum has added a temporary exhibit, “Beyond the Trenches: Stories from the Front.” See the article elsewhere in this issue. We are always looking for information, leads, and connections to Wisconsin’s aviation past. Maybe you have a relative who served during World War I. We would much appreciate hearing from you. We will share more stories and details through our social media outlets and articles in Forward in Flight as we move through the centennial “war years” 2017 and 2018. Beyond the Trenches The Wisconsin Veterans Museum (WVM) is a gem. Its exhibits of Wisconsin’s treasure, and stories of the men and women who fought and died for our country, is simply outstanding. WAHF inductees are among the many who are highlighted in their exhibits: Fritz Wolf, Rodney Williams, Lance Sijan, and nominee George Doresch. WVM recently unveiled a temporary exhibit, World War I Beyond the Trenches: Stories from The Front, earlier this spring. We visited the museum shortly after the exhibit opened. The exhibit includes many items not seen before including bullet fragments from the fuel tank of Rodney William’s Sopwith Camel. Learn the story of Mortimer Lawrence of Beaver Dam, an observer/gunner with the 104th Aero Squadron, who was credited with the last aerial victory of World War I. Mortimer’s diary entries provide the details, the exhibit brings his story to life. Did you know that more than 122,000 Wisconsinites served in the US armed forces during World War I? Almost 4,000 of them gave their lives for their country. Maybe a relative or that old guy down the street as you were growing up were among those thousands. Visit the WVM, learn more about the 32nd “Red Arrow” Division, the 42nd “Rainbow” Division, and the 86th “Blackhawk” Division. The exhibit runs through April 2019. Among other opportunities and events to expand our knowledge of World War I, the WVM is hosting a two-day symposium. World War 100: A Centennial Symposium. The event will be held in the Pyle Center on the UW-Madison campus on October 27 and 28. Speakers will include World War I experts and historians from across the country. A member of the United States World War One Commission, WVM is one of several state organizations sharing the stories of Wisconsin in World War I. Visit the commission’s website http://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/ wisconsin-wwi-centennial-home.html to learn more. Below: An exhibit from the Wisconsin Veterans Museum WWI exhibit, Beyond the Trenches. 18 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Photos by John Dorcey