Forward in Flight - Summer 2020

Volume 18, Issue 2 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Summer 2020 Latest information on the cancellation of EAA’s Oshkosh 2020 AirVenture

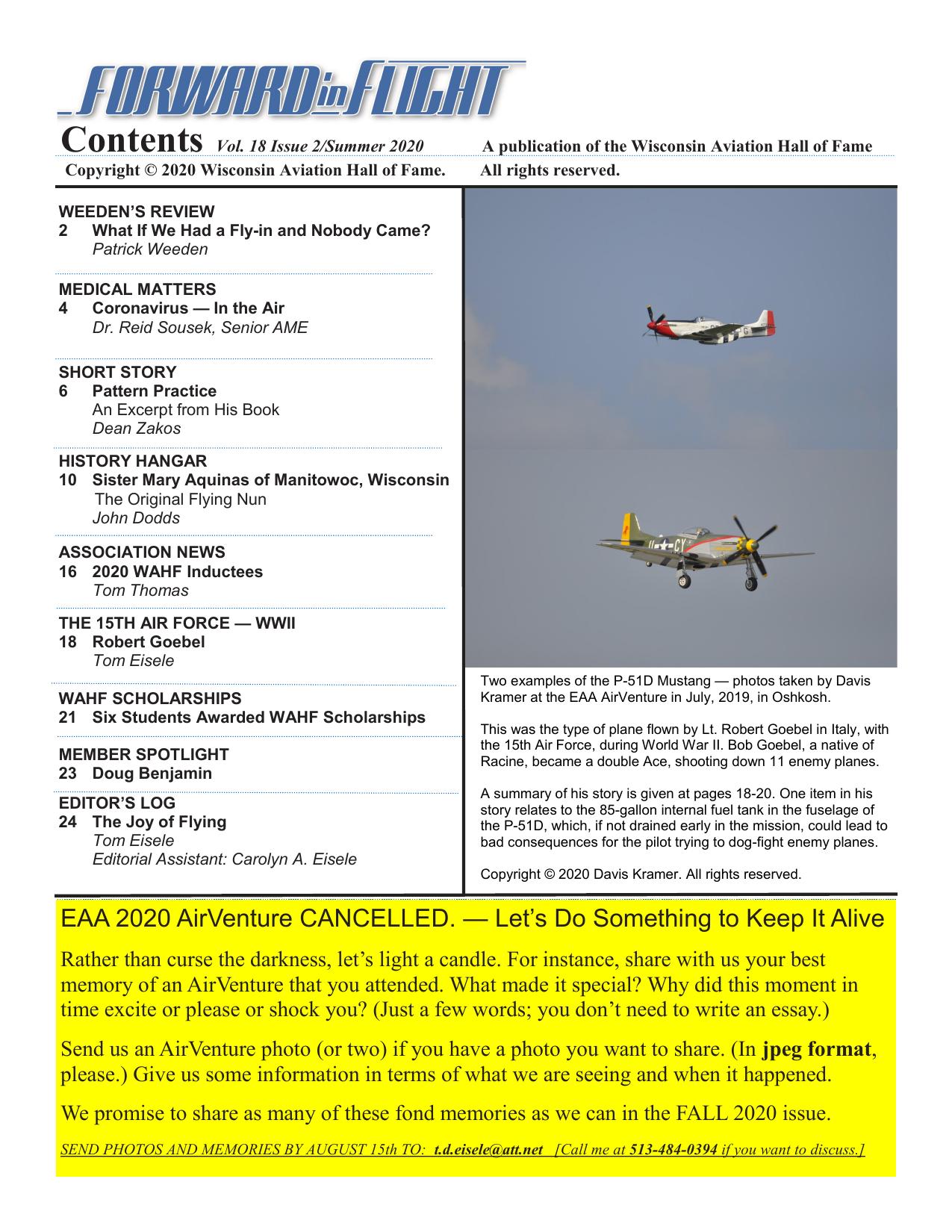

Contents Vol. 18 Issue 2/Summer 2020 Copyright © 2020 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All rights reserved. WEEDEN’S REVIEW 2 What If We Had a Fly-in and Nobody Came? Patrick Weeden MEDICAL MATTERS 4 Coronavirus — In the Air Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME SHORT STORY 6 Pattern Practice An Excerpt from His Book Dean Zakos HISTORY HANGAR 10 Sister Mary Aquinas of Manitowoc, Wisconsin The Original Flying Nun John Dodds ASSOCIATION NEWS 16 2020 WAHF Inductees Tom Thomas THE 15TH AIR FORCE — WWII 18 Robert Goebel Tom Eisele WAHF SCHOLARSHIPS 21 Six Students Awarded WAHF Scholarships MEMBER SPOTLIGHT 23 Doug Benjamin EDITOR’S LOG 24 The Joy of Flying Tom Eisele Editorial Assistant: Carolyn A. Eisele Two examples of the P-51D Mustang — photos taken by Davis Kramer at the EAA AirVenture in July, 2019, in Oshkosh. This was the type of plane flown by Lt. Robert Goebel in Italy, with the 15th Air Force, during World War II. Bob Goebel, a native of Racine, became a double Ace, shooting down 11 enemy planes. A summary of his story is given at pages 18-20. One item in his story relates to the 85-gallon internal fuel tank in the fuselage of the P-51D, which, if not drained early in the mission, could lead to bad consequences for the pilot trying to dog-fight enemy planes. Copyright © 2020 Davis Kramer. All rights reserved. EAA 2020 AirVenture CANCELLED. — Let’s Do Something to Keep It Alive Rather than curse the darkness, let’s light a candle. For instance, share with us your best memory of an AirVenture that you attended. What made it special? Why did this moment in time excite or please or shock you? (Just a few words; you don’t need to write an essay.) Send us an AirVenture photo (or two) if you have a photo you want to share. (In jpeg format, please.) Give us some information in terms of what we are seeing and when it happened. We promise to share as many of these fond memories as we can in the FALL 2020 issue. SEND PHOTOS AND MEMORIES BY AUGUST 15th TO: t.d.eisele@att.net [Call me at 513-484-0394 if you want to discuss.]

President’s Message By Tom Thomas Aviation in Wisconsin has been wrapped up with the COVID19 pandemic and the need for controlling this outbreak; plus the accelerated development of a vaccine. The loss of EAA’s AirVenture 2020 in particular leaves a void for all aviation-minded folks around the world. Our Wisconsin aviation followers across the state are all very much a part of the EAA world, and its cancellation hits especially close to home. However, AirVenture planning for 2021 is already underway. Also, we at WAHF are planning the WAHF 2020 Induction Ceremony at the EAA Museum in October, and we are anticipating being able to have 200 (+/-) attendees. We are hoping there will be a COVID-19 treatment and/or vaccine available by fall. Without that, we may have to consider postponing the ceremony, or look for other facilities if the EAA Museum is closed. The WAHF Board may also consider a winter date for the Induction Ceremony. Our newest WAHF Board Member, Pat Weeden, is also the Executive Director of the Kelch Aviation Museum Inc. on Brodhead Airport. They have recently completed the Phase I construction of their museum and have invited WAHF to store our materials and set up a WAHF display for museum visitors. The Brodhead Airport is a beautiful facility with wellmaintained turf runways On a sad note, recently a good friend and fellow pilot, Al Wilkening, with whom I had flown in the Madison Air Guard unit, lost a valiant battle with pancreatic cancer. Al was born and raised in Long Island, New York, and joined the Madison Air Guard unit in 1973 after leaving the Air Force Training Command as a T-37 IP. We first met when I transferred from the Milwaukee ANG to Madison in 1978 and was trained in the 0-2A plane that Al was flying at the time. In 1980, we both transitioned to the A-37B, and then to the A-10A, and we often flew together. We both had civilian jobs and rarely flew during the week, but we would sign up to fly the one night sortie during the week and two day sorties on Saturdays. Often on Saturday afternoons, it would be just Al and I, and we would be the only two people in the large pilot locker Forward in Flight the only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s aviation events. Tom Eisele, editor W8863 U.S. Highway 12 Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-9762 513-484-0394 t.d.eisele@att.net The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. Al and Tom, December 2017 room. Since our names were at the end of the alphabet, we were assigned lockers right next to each other. This resulted in us fighting for space on our narrow bench while climbing over flight gear. We would chew each other out for taking too much space, then laugh out-loud. I retired from the Guard in 1994 and Al moved to State Staff HQ. He was an outstanding Guardsman and ultimately became the State Adjutant General with the rank of Major General, directly reporting to the Governor. Al had leadership responsibilities for 10,000 Wisconsin soldiers, airmen, and civilians. Al was an outstanding pilot, flight lead, and wingman. He was a true master of the wild blue yonder. Safety was primary, and Al was always Mission Ready. Sadly, Al headed West on April 8, 2020. From the 115th Fighter Wing: Clear skies and tailwinds Al. Cover: Caught in the Swirl Photo from PxHere.com website, id # 1565701, released under Creative Commons CC0

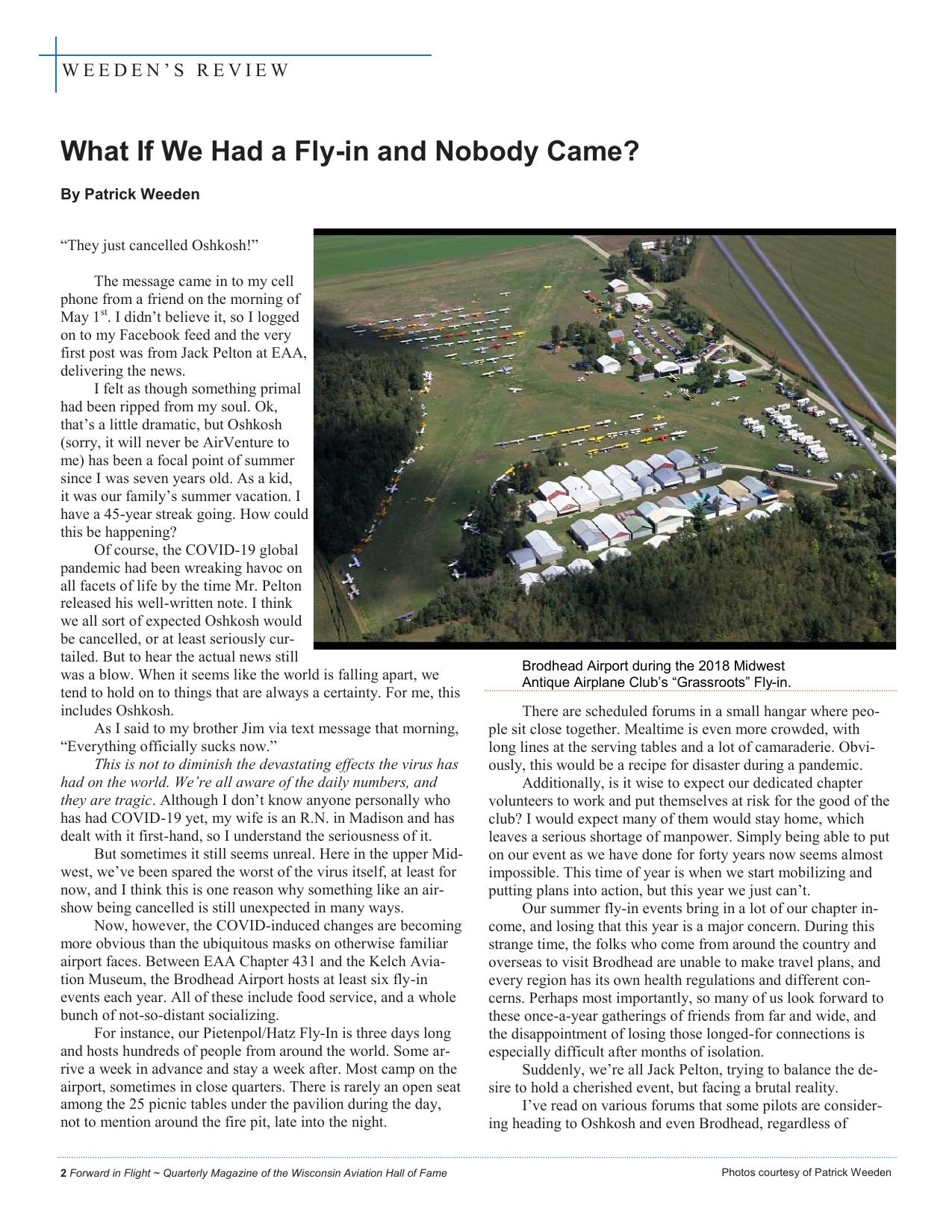

WEEDEN’S REVIEW What If We Had a Fly-in and Nobody Came? By Patrick Weeden “They just cancelled Oshkosh!” The message came in to my cell phone from a friend on the morning of May 1st. I didn’t believe it, so I logged on to my Facebook feed and the very first post was from Jack Pelton at EAA, delivering the news. I felt as though something primal had been ripped from my soul. Ok, that’s a little dramatic, but Oshkosh (sorry, it will never be AirVenture to me) has been a focal point of summer since I was seven years old. As a kid, it was our family’s summer vacation. I have a 45-year streak going. How could this be happening? Of course, the COVID-19 global pandemic had been wreaking havoc on all facets of life by the time Mr. Pelton released his well-written note. I think we all sort of expected Oshkosh would be cancelled, or at least seriously curtailed. But to hear the actual news still was a blow. When it seems like the world is falling apart, we tend to hold on to things that are always a certainty. For me, this includes Oshkosh. As I said to my brother Jim via text message that morning, “Everything officially sucks now.” This is not to diminish the devastating effects the virus has had on the world. We’re all aware of the daily numbers, and they are tragic. Although I don’t know anyone personally who has had COVID-19 yet, my wife is an R.N. in Madison and has dealt with it first-hand, so I understand the seriousness of it. But sometimes it still seems unreal. Here in the upper Midwest, we’ve been spared the worst of the virus itself, at least for now, and I think this is one reason why something like an airshow being cancelled is still unexpected in many ways. Now, however, the COVID-induced changes are becoming more obvious than the ubiquitous masks on otherwise familiar airport faces. Between EAA Chapter 431 and the Kelch Aviation Museum, the Brodhead Airport hosts at least six fly-in events each year. All of these include food service, and a whole bunch of not-so-distant socializing. For instance, our Pietenpol/Hatz Fly-In is three days long and hosts hundreds of people from around the world. Some arrive a week in advance and stay a week after. Most camp on the airport, sometimes in close quarters. There is rarely an open seat among the 25 picnic tables under the pavilion during the day, not to mention around the fire pit, late into the night. 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Brodhead Airport during the 2018 Midwest Antique Airplane Club’s “Grassroots” Fly-in. There are scheduled forums in a small hangar where people sit close together. Mealtime is even more crowded, with long lines at the serving tables and a lot of camaraderie. Obviously, this would be a recipe for disaster during a pandemic. Additionally, is it wise to expect our dedicated chapter volunteers to work and put themselves at risk for the good of the club? I would expect many of them would stay home, which leaves a serious shortage of manpower. Simply being able to put on our event as we have done for forty years now seems almost impossible. This time of year is when we start mobilizing and putting plans into action, but this year we just can’t. Our summer fly-in events bring in a lot of our chapter income, and losing that this year is a major concern. During this strange time, the folks who come from around the country and overseas to visit Brodhead are unable to make travel plans, and every region has its own health regulations and different concerns. Perhaps most importantly, so many of us look forward to these once-a-year gatherings of friends from far and wide, and the disappointment of losing those longed-for connections is especially difficult after months of isolation. Suddenly, we’re all Jack Pelton, trying to balance the desire to hold a cherished event, but facing a brutal reality. I’ve read on various forums that some pilots are considering heading to Oshkosh and even Brodhead, regardless of Photos courtesy of Patrick Weeden

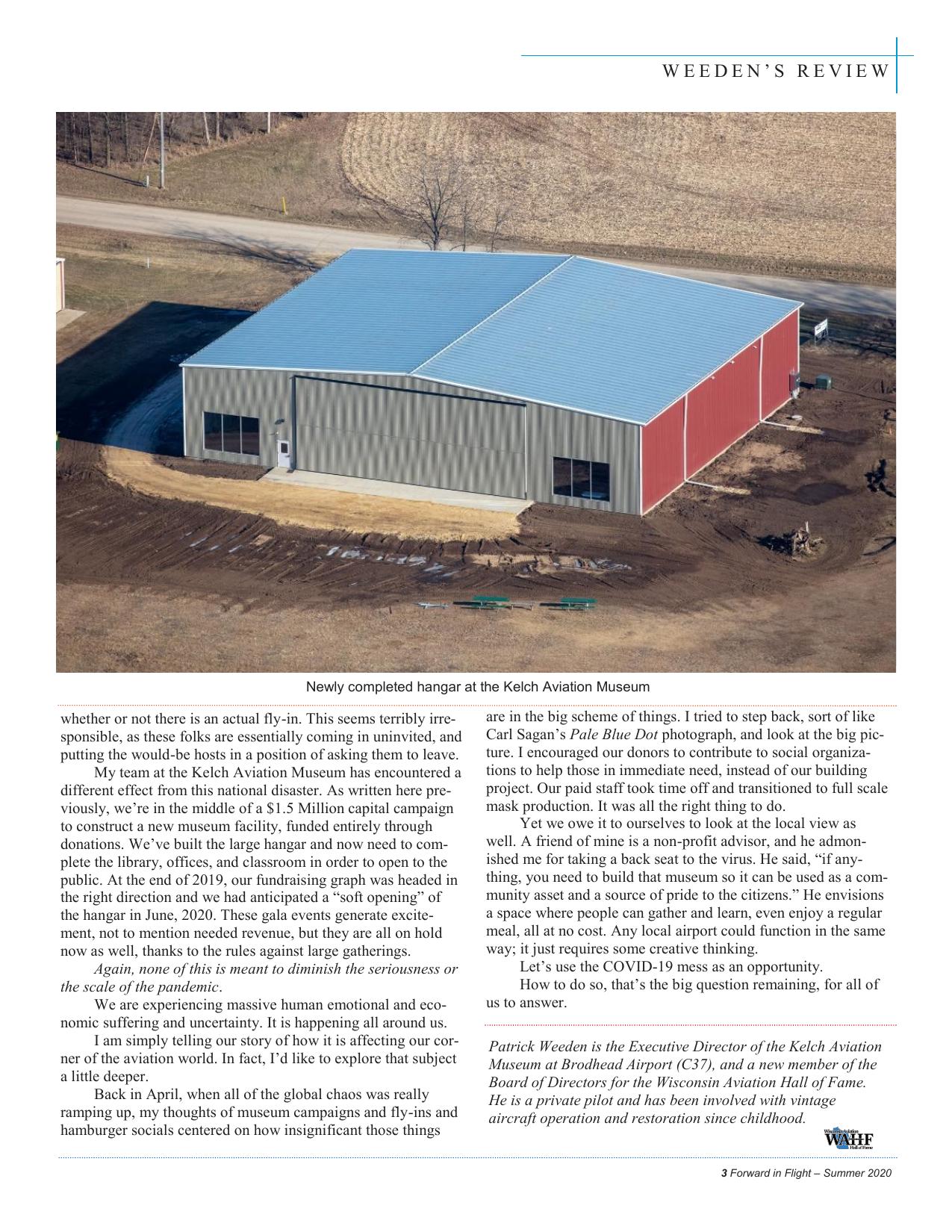

WEEDEN’S REVIEW Newly completed hangar at the Kelch Aviation Museum whether or not there is an actual fly-in. This seems terribly irresponsible, as these folks are essentially coming in uninvited, and putting the would-be hosts in a position of asking them to leave. My team at the Kelch Aviation Museum has encountered a different effect from this national disaster. As written here previously, we’re in the middle of a $1.5 Million capital campaign to construct a new museum facility, funded entirely through donations. We’ve built the large hangar and now need to complete the library, offices, and classroom in order to open to the public. At the end of 2019, our fundraising graph was headed in the right direction and we had anticipated a “soft opening” of the hangar in June, 2020. These gala events generate excitement, not to mention needed revenue, but they are all on hold now as well, thanks to the rules against large gatherings. Again, none of this is meant to diminish the seriousness or the scale of the pandemic. We are experiencing massive human emotional and economic suffering and uncertainty. It is happening all around us. I am simply telling our story of how it is affecting our corner of the aviation world. In fact, I’d like to explore that subject a little deeper. Back in April, when all of the global chaos was really ramping up, my thoughts of museum campaigns and fly-ins and hamburger socials centered on how insignificant those things are in the big scheme of things. I tried to step back, sort of like Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot photograph, and look at the big picture. I encouraged our donors to contribute to social organizations to help those in immediate need, instead of our building project. Our paid staff took time off and transitioned to full scale mask production. It was all the right thing to do. Yet we owe it to ourselves to look at the local view as well. A friend of mine is a non-profit advisor, and he admonished me for taking a back seat to the virus. He said, “if anything, you need to build that museum so it can be used as a community asset and a source of pride to the citizens.” He envisions a space where people can gather and learn, even enjoy a regular meal, all at no cost. Any local airport could function in the same way; it just requires some creative thinking. Let’s use the COVID-19 mess as an opportunity. How to do so, that’s the big question remaining, for all of us to answer. Patrick Weeden is the Executive Director of the Kelch Aviation Museum at Brodhead Airport (C37), and a new member of the Board of Directors for the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. He is a private pilot and has been involved with vintage aircraft operation and restoration since childhood. 3 Forward in Flight – Summer 2020

MEDICAL MATTERS Coronavirus — In the Air Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME At the time of my writing, we are in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, every aspect of aviation (and daily life) has been affected. New data are being released daily and protocols are often adjusted based on that data. This article will cover different changes we have, or will, encounter. Keep in mind, this is being written in late April. My Own Practice For me professionally, there have been drastic changes to workflows. Before entering work each day, I must complete an online symptom questionnaire. I then receive a color-coded check-mark on my phone. Upon entering the workplace, I must show this check mark to the screener at the door and put on my mask. All patients entering the building are screened in a similar fashion by a nurse sitting at the front door. All clinical staff and employees are wearing masks the entire work shift while in the clinic. In my occupational medicine clinic, I have been able to continue doing FAA medical exams. Many other AMEs have temporarily stopped performing pilot medical certification exams. We have temporarily avoided other non-essential clinic visits when possible. Certain tests, such as lung function testing (spirometry), have been deferred. Some work injury visits are completed with virtual/online components. On March 26, 2020, the FAA issued a document which stated that the FAA will not take any legal action against a pilot for noncompliance of medical requirements (if their medical certificate expired between 3/31/2020 and 6/30/2020). On the surface, this may look like a quick 3-month extension for all pilots. However, the wording is carefully crafted and applies only to FAA enforcement. This offers no extension for airmen flying internationally or to other jurisdictions. Additionally, aircraft owners will want to closely review the details of their insurance policies. Many of these policies will require that the pilot in command have a current medical certificate. So, how this FAA extension plays out remains to be seen; as does whether any extension beyond June 30th will occur, or not. Aviation Professionals — Their Changed Workplaces Aviation professionals have had changes in their workplaces as well. Over the past few weeks, I have spoken with multiple pilots (and Air Traffic Control) about the current status of air travel. Most have said they have been getting more direct routing than they have ever experienced previously. With fewer planes in the air, ATC is able to allow the more direct flight paths. In addition to more “direct to” routing, on departure, clearances to higher altitudes are coming quicker. Some pilots have commented on how quiet certain airspaces are; as well, at least one has landed at an airport only to find the FBO closed -- making for difficulties obtaining fuel (no NOTAM reported). 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Airline passengers and travel in general will also look different. The current empty flights will not last forever. Eventually, the country/world will get back to traveling for both business and pleasure. As I write this, JetBlue announced they would require passengers to wear masks. I am sure others will follow suit. In addition, currently, some carriers are not using the middle seat, but this is not economically viable long-term. The recirculated air in commercial airliners is usually passed through HEPA filters which in theory should remove the coronavirus. How is the Virus Spread? One of the confusing topics is how the virus is spread. Is it spread airborne? Or by way of respiratory droplets? Most of us have now heard more than enough about airborne and droplet spread of the condition from just watching the news. At the time of this writing, the thought is that this coronavirus is spread mainly by respiratory droplets. However, airborne spread may occur during certain clinical procedures. The difference between the two is important, because they lead to different precautions and protections from spread. With airborne spread, the particles are small enough that they can remain suspended in the air for long periods of time and therefore be inhaled by another individual. This is contrasted with droplet spread, which is larger particles which are too heavy to remain suspended in the air and fall to the ground or other surfaces. Respiratory droplet transmission is related to exposure within 3-6 feet. My understanding of the air-handling in commercial airliners is that about 50% of the cabin air is recycled (some aircraft use only outside air and do not recirculate, others can flip a switch to only use external air). There is a complete change of air every 2 to 3 minutes in the recirculated systems. The recirculated air is usually passed through HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filters. According to Delta’s website, these HEPA filters can filter out particles down to 0.01 micrometers. The particle size of the coronavirus is around 0.12 micrometers in size. Therefore, these filters should remove the virus (along with other contaminants, such as dust, bacteria, and fungi).

MEDICAL MATTERS Masks As a point of reference, an N95 medical mask is 95% efficient when tested against very “small” particles (approximately .3 micrometers) (source: 3M Infection Prevention N95 Particulate Respirators, 1860/1860S and 1870 FAQ). A regular surgical mask is not considered adequate for filtration, due to a loose fit. The surgical mask mainly protects others against the wearer’s respiratory emissions. The exposure risk of being in a commercial airliner is more related to droplets than due to airborne exposure. Surfaces and Proximity So, seating proximity and surface exposure are the concern more so than from air circulating in the cabin. You are more likely to “catch something” by touching a surface (and then your face) than “catching something” by breathing the air. If airborne spread of coronavirus were to occur, would we be at significant risk on an airplane? While data may become available in the future to explore this question, the nearest comparison we currently have would be to look at other infectious agents that are spread by an airborne method, such as tuberculosis. A January 28, 2016 European Surveillance review article (https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.4.30114) concluded that the risk of tuberculosis spreading on an airplane is very low. In those cases where possible spread did occur, the risk was highest in those within two rows of the infected person — possibly suggesting it was due to non-airborne spread, even though tuberculosis is considered to be an airborne pathogen. Studies have evaluated coronaviruses stability on different surfaces. In one study, the SARS-CoV-2 tested on stainless steel showed viability half-life around 5.5 hours, and on plastic showed nearly 7 hours. This means that in this lab test, half the virus were still viable at those times. Still, some virus particles did remain viable out to 72 hours. Gloves So then, we will all just wear gloves while on the plane, right? It is not that easy. In the medical setting, gloves are worn for protection (1) during invasive procedures, and (2) with contact with sterile sites, non-intact skin, bodily fluids, mucus membranes, or contaminated instruments. In the non-medical setting, gloves are worn to protect against chemicals and irritants. In other regular day-to-day life, there is generally a minimal role for gloving. Some studies show we touch our faces over 20 times an hour on average. If you touch your face after touching a contaminated surface, you risk inoculating yourself with potential pathogens, independent of whether you are gloved or not. Coronavirus specifically appears to be susceptible to both methods of hand cleansing [soap-and-water, and alcohol-based hand-sanitizer]. Basic Hygiene and Hand-Washing Thus, you are better off spending your effort on diligent hand hygiene, rather than donning and doffing gloves. Fortunately, it appears that not only hand-washing with soap and water, but also use of alcohol-based hand-sanitizers, are effective in reducing the amount of microbes on our hands. Coronavirus specifically appears to be susceptible to both methods of hand cleansing. This is not true of all pathogens, though. Clostridium difficile (C. diff ), norovirus, cryptosporidium are examples of microbes that are not effectively controlled with alcohol-based hand-sanitizers; with these particular microbes, only good old-fashioned soap and water are effective. A quick review of some airlines’ websites shows statements on airlines wiping down all hard surfaces in a plane. These statements commenting on cleansing practices will likely become a common feature on many other business websites also. Changes to food and beverage handling may also become the new norm. Some Tentative Thoughts in Closing As the commercial aviation world re-awakens after the coronavirus pandemic, we will see changes. Just as 9/11 changed our security requirements, the COVID pandemic will change our flight experiences. This may mean wearing masks, wiping down our seating area, more frequent hand-hygiene, or even health or temperature screening before boarding. Even as we grudgingly adapted to the security procedures, I would expect we also will adapt to “post-COVID” life and get back to traveling the world. Dr. Reid Sousek is an FAA-designated Senior Aviation Medical Examiner, who offers Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 Pilot Medical Exams; and an HIMS AME, for drug/alcohol exams. Dr. Sousek has offices near Oshkosh and Menasha. He graduated in 2004 from Loyola University of Chicago, Stritch School of Medicine. 5 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2020

SHORT STORY Pattern Practice An Excerpt from His Book, Laughing with the Wind By Dean Zakos The man stood next to the flagpole and felt the autumn breeze brush lightly over him. The faded colors above his head snapped lazily against a sky of broken clouds signaling that the wind was out of the southwest. A glance at the windsock confirmed it. Looking farther to the west, he could see that the sun was slowly draining itself into the horizon, beginning to take the late afternoon light with it. A cold front was coming, and a line of steel gray overcast was stretched tight on a diagonal across the sky in the distance, with broken puffs of cumulus hanging, backlighted, against the setting sun. With the front would come rain. But there was enough time. Enough time to fly. Loose gravel crunched under his feet as he walked toward the tie-down area. His light cotton jacket was open, despite the slight chill in the air, since he knew once he was in the cockpit the warmth of his body would be enough. The Piper Archer was parked in the first tie-down spot west of the taxiway. As he approached the airplane he looked at the wings and then the tail, searching for any sign of irregularity a wing down, an uneven line – any asymmetry in the otherwise clean, straight lines of leading edges, dihedrals, and wing cords. Three tie down ropes were in place. The "Remove Before Flight" ribbon fluttered beneath the well-worn cowl plugs. He walked slowly around the airplane, coming to a stop at the right wing root, and placed his flight bag on the ground. He stepped up, unlocked both door latches, and entered the cockpit, resting one knee on the right front seat. A faint, stale smell of aviation gasoline permeated the seat fabric. The bungee cord securing the control yokes was in place. He quickly unfastened it and slipped it into the pocket behind the right seat. Next, he checked the Hobbs meter and scrawled the time on the tach board he had brought with him from the clubhouse. A quick glance at the instruments, noting that the radio avionics switch was in the off position, was all he needed before he flipped on the master switch. The gyros, needles, and the low voltage light all came to life. The fuel tanks each showed three-quarters full. He rolled the stabilator trim wheel until the mark lined up for normal takeoff position. He reached down between the seats and slowly pulled up on the flap handle, waiting to hear each successive click as the flaps extended. With a quick look around, he pressed the master switch back to the "off" position and exited the airplane. Preflighting an airplane had become second nature to him. He knew what to look for; he knew where to look. He knew what the airplane felt like; he knew what it smelled like. And he knew, after walking around one last time and performing all of the checks he knew so well, that the airplane was ready to fly. 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame He adjusted the seat and buckled himself in. The two prongs of the cord attached to his headset slipped easily into place on the lower left corner of the instrument panel. The headset, with its familiar green ear cups, was balanced on top of the panel just to the left the compass. His movements now became slow and deliberate as he scanned the "Starting Engine" checklist. A couple of shots from the primer. Throttle pumped three times and opened just a scootch. Master switch on. Electric fuel pump on. Mixture to full rich. Rotating beacon on. Confirm that no one is around the airplane. Open the storm window. "Clear!" The engine turned over slowly at first, so slowly he thought he could almost count the spinning prop blades. As he cranked, he pumped the throttle twice. The engine caught. He knew it would catch, expected it to catch. The engine vibration was steady, comfortable. He settled into the left seat, rocked slightly, and scanned the instruments. R-O-R-F-L-D. Rpm one thousand. Oil pressure in the green. Radio avionics switch on. Flaps up. Lights. Directional gyro set. Brakes released, throttle forward, slowly the airplane began to taxi across the matted grass toward the single paved runway. "Westosha Traffic, Archer 2241 PAPA back-taxiing Runway 21, Westosha." Turning to the right, the Archer bumped onto the hard surface of the runway and began tracking the faded white centerline. After the run-up, he was ready to go. He looked down the strip, making sure it was clear, and then once more looked at the sky, verifying that no one was on short final or had sneaked into the traffic pattern unannounced. "Westosha Traffic, Archer 2241 PAPA departing Runway 21, Westosha. Staying in the pattern." Glancing again at the instruments, he confirmed he was ready to go. Full aileron deflection into the wind. Smoothly to full throttle. Track the runway centerline. Right rudder. Roll out the aileron slowly. Good RPM. Good oil pressure. Fiftynine knots. Rotate. He pulled back on the yoke and the Archer lifted easily into the air. Tracking the runway heading, the ground slipped away beneath him. Flagpole and clubhouse passed under the left wing. Rpm good. Oil pressure good. Wings level. Heading is two one zero degrees. "Westosha Traffic, Archer 2241 PAPA departing Runway 21, Westosha. Staying in the pattern for a touch-and-go." At one thousand three hundred feet, he started his left turn, using aileron and rudder to bank the airplane into the first leg of the rectangular pattern. The low clouds had started to move in. © Dean R. Zakos 2019 All Rights Reserved. Images by the author.

SHORT STORY Sticky puffs of cotton, some smudged and dirty, as if they had been dragged along a garage floor, floated in clumps or were stretched thin by the wind just overhead. TPA was one thousand five hundred feet. The clouds would easily be a few hundred feet higher. But still close enough to see them - really see them - in a way he never could see them when he was standing on the ground. Close enough, at times, that he thought he could almost reach out and touch them. See them stream through his fingers. Feel the cold, damp chill. Know what it was like to be in a place where, as a small boy, he thought only angels could know. As he reached one thousand five hundred feet he throttled back and began his turn downwind, pointing the nose of the airplane to a heading of zero three zero degrees. "Westosha Traffic, Archer 41 POP entering left downwind for Runway 21, Westosha." He crabbed slightly to compensate for the light crosswind. The sun was setting. Its fading light continued to backlight the approaching clouds stretched across the horizon. The area surrounding the airstrip, cast in its patchwork quilt of fall browns and golds, spanned out beneath him, and the flat black ribbon of runway, intersected by his left wing tip, was neatly parallel to his path of flight. The twin lakes to the west shimmered in the remnants of the late afternoon light. B-G-U-M-P-C. Boost on. Gas on fullest tank. Undercarriage down. Mixture full rich. Prop. Carb heat. He touched each lever or noted each item as he went through his short checklist. Photo image courtesy of Dean Zakos He looked first at the runway, then the tie-down area, looking to see if there was other traffic he would need to locate. The clubhouse was at the southwestern end of the runway, with a row of T-hangars running alongside to just before the end. The T-hangars had red and white striped roofs. Somebody had thought that this color scheme would improve visibility. It did, but was really only of use during the summer months, when the dark green of the grass made the small structures stand out at a distance of a few miles. Looking straight ahead again, he adjusted the pitch attitude slightly, inched the throttle back to achieve 2100 rpm, and confirmed the altitude of one thousand five hundred feet. No traffic on the ground. No traffic in the pattern. The airplane was now almost opposite the spot on the runway where the man intended the airplane to touch down. He throttled back to 1500 rpm and adjusted the nose of the aircraft to a point just above the horizon that he knew would give him best glide pitch attitude and airspeed. This was the part he liked best. With the engine almost at idle, the Archer was gliding gracefully back to earth. With best glide pitch attitude, the airspeed started to fall. As the needle passed into the white arc of the airspeed indicator, the man reached for the flap handle. He pulled it up, stopping at the first audible detent in the mechanism - one notch. Flaps down, nose down. The man adjusted the pitch attitude slightly to maintain 7 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2020

SHORT STORY seventy-five knots of indicated airspeed. The end of the runway had passed under the left wingtip of the Archer and the distance between them was now increasing. Looking first forward, then at the airspeed, the man looked several times over his left shoulder at the runway. He then scanned forward again, extending himself slightly to see any traffic which may have been approaching from the north. When the angle between the intended touchdown point and the position of the Archer appeared to be about fortyfive degrees, he banked the airplane to the left. "Westosha Traffic, Archer 41 POP turning left base for Runway 21, Westosha." He gently rolled the airplane out of the turn with the directional gyro indicating three zero zero degrees. The sun was nestled comfortably between the horizon and clouds now. The sky to the west had been painted in soft pastels by a master’s brush. Airspeed seventy-five knots. Key position. Distance looks good. Altitude looks good. Add one notch of flaps. Flaps down, nose down. The Archer was gliding northwest, descending steadily, predictably, traveling a line perpendicular to the runway, between one-half and three-quarters mile away. The man looked ahead, checked his airspeed, looked to his right, and then looked down the left wing, locating the runway threshold. He didn't know how many times he had landed an airplane. You could have asked to see his logbooks. The ratings, the aircraft, the trips, the significant events were all recorded there. "An equal number of take-offs and landings," he would have said dryly to the person posing such a question. You might as well have asked him how many times he had cut the grass in the tie-down area or how many gallons of gasoline he had pumped into the wing tanks of the club airplanes when he was a teenager. After a while, the number of hours no longer had any real meaning. It wasn't the number that was important anyway. It was the experience. For him, flying an airplane, landing an airplane, was an experience like no other. It wasn't like work, or sports, or trying to get along with people he didn't really care for. It was planning, and experience, and using his head to manage. Almost everything about his flying depended on him. He made the decisions; he complied with the rules; he anticipated, and acted, and reacted. It was satisfying and challenging, and just plain fun, in so many ways that life's other endeavors, both small and large, were not – and could never be. Looking to his right, then swiveling his head left, the man checked for traffic again. No traffic. No radio chatter. "Westosha Traffic, Archer 41 POP turning final for Runway 21, Westosha. Touch-and-go." As the man keyed the microphone, he turned the yoke to the left and touched the left rudder pedal, causing the Archer to enter a gentle bank. He held the turn until the white spinner of 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame the propeller lined up just off center of the extended centerline of the runway, crabbing slightly for the crosswind. The aircraft was now on a glide path the center of which would bring the Archer straight down to the middle of the runway threshold. From this position the world always looked beautiful. The runway numbers and markings, painted white against the darker background of the asphalt, stood out against the pavement, occupying a spot approximately one-half the way down the windshield in front of him. “Just keep the numbers there and watch them grow larger,” his primary instructor used to say. If the numbers started moving up, he knew he was falling below the intended glide path. If the numbers started moving down, he knew he was above the intended glide path. The numbers didn't move. They stayed put. The man used the controls judiciously, making small corrections as needed to keep the numbers centered. Airspeed seventy knots. Descending at about four hundred feet per minute. Flap handle. Add the last notch of flaps. Flaps down, nose down. The runway threshold for 21 always looked a little imposing for newcomers. It wasn't what every pilot was used to. The runway itself was fine, not as long or wide as some, with two thousand eight hundred fifty feet in length and a thirty-eight foot width. At the threshold of 21 was a drop-off of some thirty or forty feet, opening into a shallow valley wedged between the surrounding farm fields. You wouldn't want to be short coming in at this end. The man thought back to that early evening when he was returning from his first check ride. He had earned his private license that late November afternoon, and flew back to Westosha in the gathering darkness. He called about five miles out. Mel was still in the clubhouse finishing the last of the day's coffee. "I'll put the lights on for you," he said. As the man thought back to that day, he smiled to himself. For a moment, he was once again on that short final. The air was still that night, and the twin rows of runway lights sparkled invitingly before him as he gently glided earthward. He would always remember that landing in the dying light at the end of that day. Photo image courtesy of Dean Zakos

SHORT STORY The Archer's airspeed was now at sixty-six knots. Small control inputs, pitch for airspeed, power for altitude, kept the light airplane on its intended course. From this point, the Archer could glide in on its own. The man knew he had the runway made. He throttled the engine back to idle. He pitched the nose up slightly and the airspeed hovered at about sixty knots. The runway numbers flashed under the wings. He applied slight back pressure to the yoke, causing the nose to move gently upward, and leveled the airplane about fifteen to twenty feet above the runway. As the man held this attitude, keeping the wings level and the nose tracking above the runway centerline, the aircraft's speed began to bleed off. The man now looked down the left side of the engine cowling to a moving spot about two hundred feet out and equi-distant between the runway centerline and the edge of the runway. As he focused on this distant spot, he began to sense the deceleration of the aircraft and continued to apply slight back pressure to the yoke. The Archer continued to slow and settle. Each moment brought the minute, familiar sensations of pitch, bank, and yaw as the aircraft passed over the asphalt. Track the centerline. Bank a little right. Left rudder pedal. Back pressure. Track the centerline. Bank a little left. The Archer’s mains were barely above the surface. Airspeed continuing to decelerate. Pull the yoke back. Slowly. Slowly. Back ... Back ... Back. The rubber tires chirped lightly as they contacted the abrasive surface. Hold the nose wheel off. Off. Now, let it down gently. Gently. On the runway centerline. Full aileron deflection into the wind. Flaps up. Smoothly to full power. Adjust the ailerons. Right rudder. Track the runway centerline. 2700 RPM. Fifty-nine knots. Rotate. "Westosha Traffic, Archer 2241 PAPA, departing Runway 21, Westosha, staying in the pattern." The man didn’t need to think about the just completed landing, although he felt pleased. Pleased to be flying. He would think more about it later. Now a few small drops of rain were spattering on the windshield, smearing the fall colors and the scenery below. He flew the rectangular pattern twice more that afternoon. Each time he flew it, he thought about the small corrections that he would need to make, the perceptive adjustments that would result in the Archer being at the right airspeed at the right position in the pattern at the right time. And he would think of other memories and special times in his life. He knew he was happiest when he was flying. The Archer exited the runway and pulled on to a narrow concrete taxiway. The man stepped hard on the right rudder Photo image courtesy of Dean Zakos pedal, resulting in a sharp turn into the first open tie-down spot. He reached over and retarded the throttle while in the turn. The aircraft rolled slowly forward, engine at idle, propeller whistling softly, until the tie down ropes, lying coiled in the grass, disappeared under the wings. The man touched the toe brakes, easing the pressure at the last instant, bringing the Archer to a smooth stop. He methodically went through the "Stopping Engine" checklist, pulling the mixture and waiting for the shudder of the engine as it gasped for fuel before going silent. The only sounds remaining were the gyros spinning down and the light rain skidding intermittently on the aluminum skin of the aircraft. The lingering smell of the warm engine mixed with the scent of the man's own perspiration in the cramped cockpit. The man unbuckled his safety belt. As he stepped down from the wing he looked up into the mottled gray sky. The small, cold droplets softly pelted his face. He stood next to the Archer for a moment. He did not have to say it. He did not even have to think it. He knew in his heart he loved to fly. He knew he always would. * * * [Dean Zakos learned to fly at Batten Field in Racine (KRAC) and at the Westosha airport in Westosha (5K6). Dean was born in Fond du Lac, and currently lives in Madison. He is a member of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), the EAA, and several local chapters of the EAA. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin—Madison, and he has a law degree from Marquette University Law School. Laughing with the Wind: Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot (Square Peg Books, 2019), is available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Square Peg Bookshop.] 9 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2020

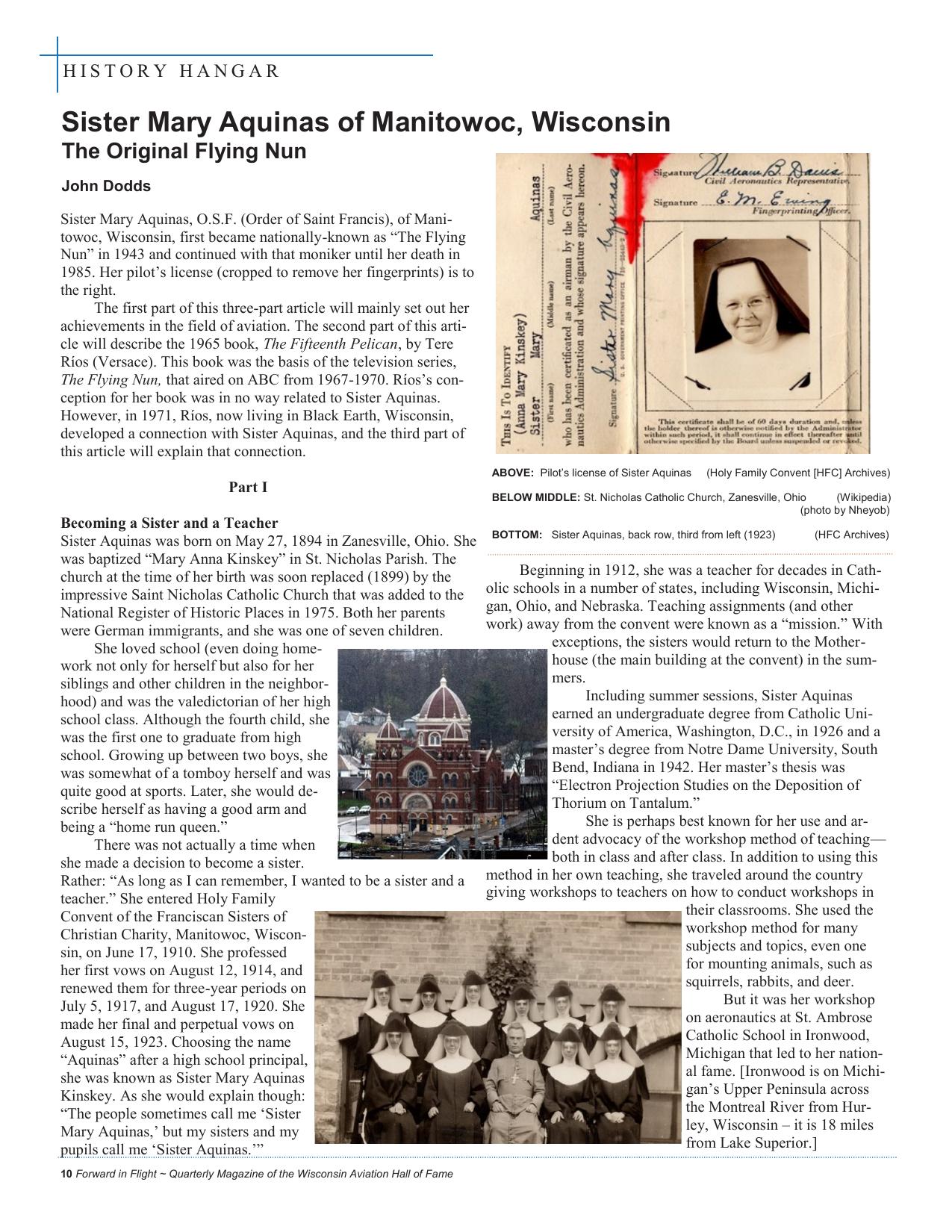

HISTORY HANGAR Sister Mary Aquinas of Manitowoc, Wisconsin The Original Flying Nun John Dodds Sister Mary Aquinas, O.S.F. (Order of Saint Francis), of Manitowoc, Wisconsin, first became nationally-known as “The Flying Nun” in 1943 and continued with that moniker until her death in 1985. Her pilot’s license (cropped to remove her fingerprints) is to the right. The first part of this three-part article will mainly set out her achievements in the field of aviation. The second part of this article will describe the 1965 book, The Fifteenth Pelican, by Tere Ríos (Versace). This book was the basis of the television series, The Flying Nun, that aired on ABC from 1967-1970. Ríos’s conception for her book was in no way related to Sister Aquinas. However, in 1971, Ríos, now living in Black Earth, Wisconsin, developed a connection with Sister Aquinas, and the third part of this article will explain that connection. ABOVE: Pilot’s license of Sister Aquinas Part I (Holy Family Convent [HFC] Archives) BELOW MIDDLE: St. Nicholas Catholic Church, Zanesville, Ohio (Wikipedia) (photo by Nheyob) Becoming a Sister and a Teacher (HFC Archives) Sister Aquinas was born on May 27, 1894 in Zanesville, Ohio. She BOTTOM: Sister Aquinas, back row, third from left (1923) was baptized “Mary Anna Kinskey” in St. Nicholas Parish. The Beginning in 1912, she was a teacher for decades in Cathchurch at the time of her birth was soon replaced (1899) by the olic schools in a number of states, including Wisconsin, Michiimpressive Saint Nicholas Catholic Church that was added to the gan, Ohio, and Nebraska. Teaching assignments (and other National Register of Historic Places in 1975. Both her parents work) away from the convent were known as a “mission.” With were German immigrants, and she was one of seven children. exceptions, the sisters would return to the MotherShe loved school (even doing homehouse (the main building at the convent) in the sumwork not only for herself but also for her mers. siblings and other children in the neighborIncluding summer sessions, Sister Aquinas hood) and was the valedictorian of her high earned an undergraduate degree from Catholic Unischool class. Although the fourth child, she versity of America, Washington, D.C., in 1926 and a was the first one to graduate from high master’s degree from Notre Dame University, South school. Growing up between two boys, she Bend, Indiana in 1942. Her master’s thesis was was somewhat of a tomboy herself and was “Electron Projection Studies on the Deposition of quite good at sports. Later, she would deThorium on Tantalum.” scribe herself as having a good arm and She is perhaps best known for her use and arbeing a “home run queen.” dent advocacy of the workshop method of teaching— There was not actually a time when both in class and after class. In addition to using this she made a decision to become a sister. method in her own teaching, she traveled around the country Rather: “As long as I can remember, I wanted to be a sister and a giving workshops to teachers on how to conduct workshops in teacher.” She entered Holy Family their classrooms. She used the Convent of the Franciscan Sisters of workshop method for many Christian Charity, Manitowoc, Wisconsubjects and topics, even one sin, on June 17, 1910. She professed for mounting animals, such as her first vows on August 12, 1914, and squirrels, rabbits, and deer. renewed them for three-year periods on But it was her workshop July 5, 1917, and August 17, 1920. She on aeronautics at St. Ambrose made her final and perpetual vows on Catholic School in Ironwood, August 15, 1923. Choosing the name Michigan that led to her nation“Aquinas” after a high school principal, al fame. [Ironwood is on Michishe was known as Sister Mary Aquinas gan’s Upper Peninsula across Kinskey. As she would explain though: the Montreal River from Hur“The people sometimes call me ‘Sister ley, Wisconsin – it is 18 miles Mary Aquinas,’ but my sisters and my from Lake Superior.] pupils call me ‘Sister Aquinas.’” 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame

HISTORY HANGAR Aeronautics Workshop and Becoming a Pilot Sister Aquinas’s workshop on aeronautics involved not only the theory of flight but also the building of model airplanes. Students designed the planes, using individual sticks of balsa wood they would select from the “woodpile.” Later, they built the models from kits in the interest of time. There were three types of models: the basic glider, a plane powered by a rubber band, and a plane powered by a small gas engine. She traveled to Chicago to buy the balsa wood from Carl Goldberg, a noted designer of model airplanes. He also traveled to give demonstrations, and Sister Aquinas had him come to her school several times. He was later inducted in the first class of the Model Aviation Hall of Fame. To further her knowledge of airplanes, she (and a couple other sisters) took flying lessons in the summer of 1942 at the Manitowoc airport. Since she could drive, she would drive to the convent near the airport (Holy Innocents) twice a week to spend the night. Alfred Haen (later manager of the West Bend, Wisconsin airport) from the airport would pick them up at 5:30 the next morning and take them to the airport for their lesson. Their lessons were over by 7:00 a.m., allowing them to have breakfast back at the Holy Innocents convent and then be back to the Mother House by 9:00 a.m. They also had flights at noon and night but not in bad weather. Here is part of her description of flying: And I can’t begin to tell you how wonderful it was to see those clouds of fog roll in from the lake and roll over Manitowoc and fly up and through that fog and into the bright sunshine and into the blue sky and looking over the city of Manitowoc with the crosses of those churches peaking up through that cloud. And you surely saw the silver lining of those clouds. Nobody can ever have the experience that you have in this, in riding airplanes. However, she repeatedly made clear that she learned to fly not to have a career in flying—it was only to make her a more knowledgeable and better teacher. Catholic University and National Fame Upon observing her workshop, a Michigan school inspector recommended her for a teaching position at Catholic University. As a result, she became the head of Air Age Education with two other sisters as assistants in the summers of 1943 and 1944. The purpose of her classes was to teach other sisters so that they in turn could teach aeronautics to their high school classes. Her courses can generally be described as pre-flight instruction, including topics such as aircraft structure, theory of flight, meteorology, and radio/communications. The courses were conducted under the auspices of the Civil Aeronautics Authority. Media coverage was scant prior to her going to Washington: “Flying Nun Becomes an Aviation Instructor” (The Racine Journal-Times, May 4, 1943) “Flying Nun, Sister Friend Chart Course” (The Wisconsin State Journal, May 30, 1943) “Sister Aquinas, Flying Nun” (The Charlotte Observer, May 16, 1943) Once her classes started, newspaper coverage exploded across the country. In the month of June 1943 alone, there were about 75 newspaper articles from 25 states referring to her as the “Flying Nun.” Extensive coverage in the newspapers continued that year until the classes were over that summer. In June 1943, Ann Rosener, a photographer from the Office of War Information, took a number of photographs of Sister Aquinas and her students, some of which appeared in the newspapers. The photograph above shows her putting some glue on a model of a P-38. That was the plane flown by Dick Bong who had the most aerial victories (40) in World War II and was known as the “Ace of Aces” (Forward in Flight, Spring 2019). Flying out of New Guinea, Bong achieved his 11 th aerial victory that month by shooting down a Japanese fighter (Nakajima Ki43 “Oscar”). After her time at Catholic University and for many years, she was asked to speak and give demonstrations in schools not only directly to children but also to teachers to help them in teaching aeronautics and other subjects. In addition, she spurred and helped the formation of hundreds of aviation clubs in the schools for all children, not just those in high school. “The Pilot” – Television Show In November 1956, CBS aired a one-hour show on Sister Aquinas as part of its Studio One drama series. The show portrayed Sister Aquinas and her workshop method of instruction, focusing primarily on her workshop on aeronautics. Nancy Kelly, a wellknown actress, portrayed Sister Aquinas and was nominated for an Emmy award in the category of “Best Single Performance by an Actress.” Margaret Sullavan, another famous actress, was Nancy Kelly, “The Pilot” (CBS) to have portrayed Sister Aquinas, but she backed out on the date the play was to be aired (October 8th). The show was delayed until November 12. Caption and credit for P-38 photo: Sister Aquinas at Catholic University, Library of Congress. 11 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2020

HISTORY HANGAR Sister Aquinas reviewed the script beforehand and marked her changes in blue pencil. One of her comments objected to a greeting of “Hi, Jeff” to a student. In blue pencil, she circled the word “Hi” and wrote in the word “Hello” and also stated, “You shouldn’t have me using slang.” [Interestingly, this show was the first film credit for Jerry Stiller, who later regularly appeared on “Seinfeld” and “The King of Queens.” He recently passed away in May 2020.] Sister Aquinas appeared at the end of the broadcast, stating in part: It [the program] shows some scenes of workshop activity in classrooms. Many teachers are interested in this method of instruction, so our work is only beginning. We need many colleges to instruct teachers in this method of education. We ourselves are planning on erecting such a college. This television program was part of a larger plan that would include a follow-on book and a feature film, thus providing the funds for the new college (actually, an addition to the existing Holy Family College). The two key outside persons involved in this effort were Robert Guiterman, manager of the Capitol Theater on 8 th Street in Manitowoc, and Bryan D. Stoner, manager of the central division of Paramount Film Distributing Corp., based in Chicago, Illinois. On November 27, 1956 (two weeks after the show aired), Guiterman, Stoner, Sister Aquinas, and Mother Superior met to discuss the terms of an agreement for a feature film on the life of Sister Aquinas. Guiterman was the “aide” to the Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity. The Sisters were to have approval of the screenplay, script, and dialogue, and would have financial participation in the “feature motion picture.” They would also have to agree to the producer, director, talent for lead roles, etc. Following the meeting, Stoner wrote to Guiterman: I can’t begin to put into words the appreciation I feel for the tremendous help you gave in finalizing this matter, to say nothing of the debt of gratitude that is owed for you suggesting the story and arranging with the Sisters to do nothing with anyone without your sitting in. On the same day, he wrote to Mother Superior: Words cannot express the thrill that is and has been mine since our meeting Tuesday. I have the utmost confidence that when the dream, if it can be called that, that was the substance of our conversation Tuesday is a reality in the form of a finished motion picture, you will be pleased and proud far beyond your present imagination. In furtherance of this effort, Sister Aquinas soon made a number of audio tapes describing her life up until the time of the tapes: 1957. There are many references in the tapes to a resulting motion picture. There are also times where she gives suggestions for the film as if she is talking to someone, even using 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame the word “you” a couple times. Most likely, that “you” is Bryan Stoner because she mentioned at one point adding some material based on his earlier comments. [The tapes total over nine hours of time and have been transferred to CDs. These sound recordings (along with transcripts that were later prepared) are at the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives in Madison, Wisconsin.] It is not clear whether this agreement was ever signed. As for the proposed book, it was decided that it would be written by one of the sisters rather than an outside author. A sample questionnaire was mailed to many people who were acquainted with Sister Aquinas over the years, and there were numerous responses. The book effort was not supposed to detract from that sister’s other duties. However, it was an overwhelming task, and the book was never written. Nor was a film ever made. Sister Aquinas in B-52 simulator (HFC Archives) Air Force Association Award The Air Force Association (AFA) is a voluntary civilian organization independent of the Department of the Air Force. Its mission is to educate the public on the need for aerospace power, advocate for aerospace power, and support air and space forces. The AFA holds an annual convention where it presents a number of awards and publishes the monthly Air Force Magazine. The 1957 AFA Convention celebrated the Jubilee Anniversary (50 years) of the Air Force. The Aeronautical Division of the U.S. Army Signal Corp was established in 1907. For her work in air-age education based in large part on her workshops, Sister Aquinas received an award for “Outstanding Contributions to the Advancement of Airpower in the Interest of National Security and World Peace” (plaque shown at right). Mrs. Carl Spaatz, wife of Carl “Tooey” Spaatz, the first Credit: Air Force Association award, HFC Archives.

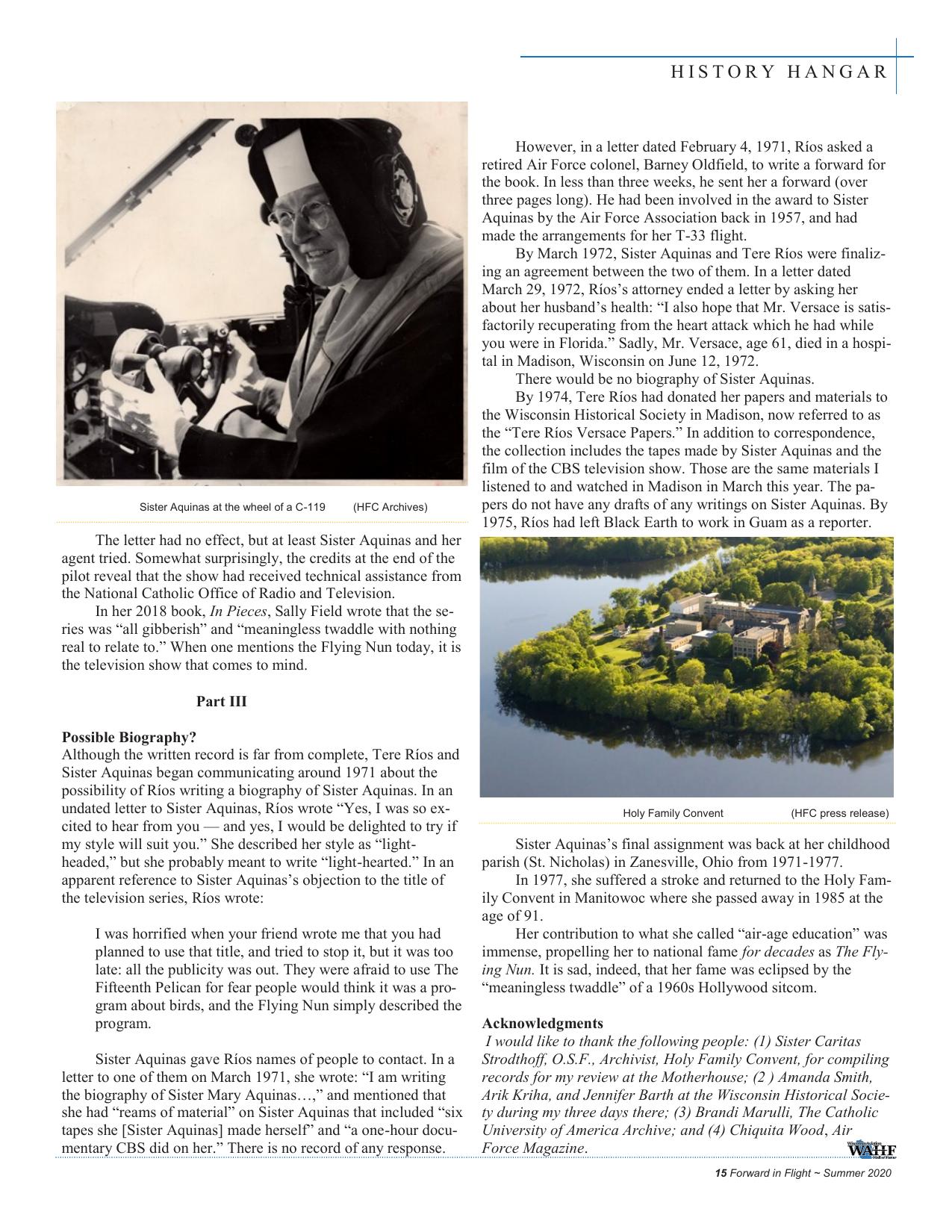

HISTORY HANGAR Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, presented the award to her. The picture to the right shows Sister Aquinas with Joanne Alford who was designated “Miss Airpower.” [Alford was a recent Purdue University graduate and while at Purdue went on several dates with Neil Armstrong—later the first man on the moon.] The next issue of Air Force Magazine reported Sister Aquinas’s award and referred to her as “the famous ‘Flying Nun.’” Flights and Visits At the AFA convention, Sister Aquinas “cornered” four-star Air Force general Earle Partridge, Commander of North American Defense Command in Colorado Springs, and told him she had two unanswered prayers: go to heaven when she died, and fly a jet. He told her he could not help with the first one, but he could with the second. And so it came to be that later that month, she flew as a passenger in a T-33 trainer jet from Truax Field, Madison, Wisconsin, to McGuire A.F.B., New Jersey. The plane was the “personal plane” of General Partridge. The plane was piloted by a major on his staff, but she handled the controls briefly along the way. The plane traveled 525 miles per hour and was “painted” numerous times by military radar sites. The actual purpose of her trip was to conduct a workshop in Morristown, New Jersey. Several years later (July 1959), she conducted a workshop in San Francisco and arranged for her students to fly on a C-119 “Flying Boxcar.” The plane took off from and landed back at Hamilton A.F.B., California; during the flight Sister Aquinas flew the plane for a time. In addition to these two military flights, she had occasion to visit military bases to observe military planes C-119 “Flying Boxcar” (U.S.A.F.) and other equipment, including a KC-97 tanker (Otis AFB, Massachusetts), a Nike-Ajax missile at the U.S. Army Air Defense School (Ft. Bliss, Texas), and the maintenance shops at Alameda Naval Air Station (Alameda, California), and a B-52 simulator. In addition, Sister Aquinas was a member of the Civil Air Patrol and received a service award from the USO (United Services Organization, Inc.). It cannot be emphasized enough that in the extensive media coverage of her travels to conduct workshops over many years and all around the country, she was invariably referred to as the “Flying Nun.” And that was especially true for the years 1943 to 1967. The latter year will become significant in the next part of this article. Credits: Sister Aquinas and Joanne Alford (top), Air Force Association; and Front cover, The Fifteenth Pelican (right), book at HFC Archives. Part II The Fifteenth Pelican In December 1965, the book The Fifteenth Pelican by Tere Ríos was published. It is the book upon which the television series “The Flying Nun” (1967-1970) was based. The book was in no way related to Sister Aquinas. However, Tere Ríos and Sister Aquinas linked up in 1971 as we shall see in Part III. Tere Ríos Versace (her pen name was Tere Ríos) was the wife of a career Army officer, Humberto Roque Versace (West Point Class of 1933) whom she married in 1936. From 1955-1959, they lived in Madison, Wisconsin (on Flambeau Street) while he was the senior Army advisor to the Wisconsin National Guard. Following his retirement in 1962, they bought a farm and moved to Black Earth, Wisconsin. A devout Catholic, she was a prolific author who wrote many articles and three books over the years (beginning in the late 1940s). Many of her writings had religious themes. The Fifteenth Pelican was her third book. The book is about Sister Bertrille of the Daughters of Charity, weighing 75 pounds and described as probably the smallest nun in the world. The veil (headdress) of that order was called a “cornette” and was quite distinctive. Ríos described the folded cornettes “like big white birds in flight.” Apart from the book, Daughters of Charity were sometimes referred to as “God’s Geese.” Newly-arrived in Puerto Rico from New York, Sister Bertrille discovered that with the gusty winds in Puerto Rico, she could fly with the combination of her low weight and the airfoil formed by her cornette (by raising her arms she could make more of an airfoil). As Ríos explained, flight is possible where “lift + thrust is greater than load + drag.” Ríos knew about flying because she had been a pilot in the Civil Air Patrol. At night, Sister Bertrille would join the end of a formation of 14 pelicans as they flew over the convent. On one flight at night, the pelicans swooped in over a secret military installation, but Sister Bertrille could not maneuver out and crash landed. In a humorous chain of events, she was apprehended by military personnel, interrogated by a civilian from some unnamed intelligence agency, taken before a judge, and finally released back at the convent. 13 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2020

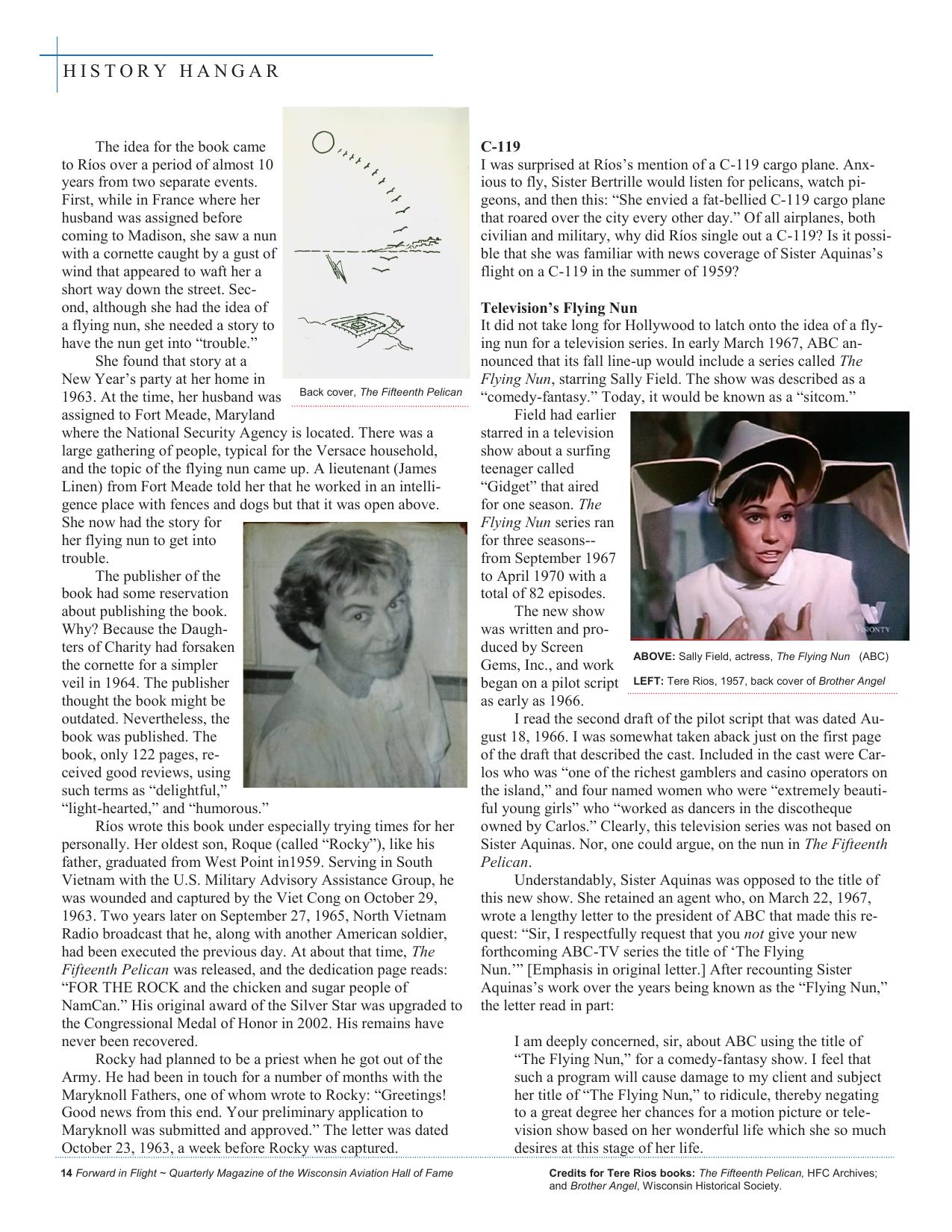

HISTORY HANGAR The idea for the book came to Ríos over a period of almost 10 years from two separate events. First, while in France where her husband was assigned before coming to Madison, she saw a nun with a cornette caught by a gust of wind that appeared to waft her a short way down the street. Second, although she had the idea of a flying nun, she needed a story to have the nun get into “trouble.” She found that story at a New Year’s party at her home in 1963. At the time, her husband was Back cover, The Fifteenth Pelican assigned to Fort Meade, Maryland where the National Security Agency is located. There was a large gathering of people, typical for the Versace household, and the topic of the flying nun came up. A lieutenant (James Linen) from Fort Meade told her that he worked in an intelligence place with fences and dogs but that it was open above. She now had the story for her flying nun to get into trouble. The publisher of the book had some reservation about publishing the book. Why? Because the Daughters of Charity had forsaken the cornette for a simpler veil in 1964. The publisher thought the book might be outdated. Nevertheless, the book was published. The book, only 122 pages, received good reviews, using such terms as “delightful,” “light-hearted,” and “humorous.” Ríos wrote this book under especially trying times for her personally. Her oldest son, Roque (called “Rocky”), like his father, graduated from West Point in1959. Serving in South Vietnam with the U.S. Military Advisory Assistance Group, he was wounded and captured by the Viet Cong on October 29, 1963. Two years later on September 27, 1965, North Vietnam Radio broadcast that he, along with another American soldier, had been executed the previous day. At about that time, The Fifteenth Pelican was released, and the dedication page reads: “FOR THE ROCK and the chicken and sugar people of NamCan.” His original award of the Silver Star was upgraded to the Congressional Medal of Honor in 2002. His remains have never been recovered. Rocky had planned to be a priest when he got out of the Army. He had been in touch for a number of months with the Maryknoll Fathers, one of whom wrote to Rocky: “Greetings! Good news from this end. Your preliminary application to Maryknoll was submitted and approved.” The letter was dated October 23, 1963, a week before Rocky was captured. 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame C-119 I was surprised at Ríos’s mention of a C-119 cargo plane. Anxious to fly, Sister Bertrille would listen for pelicans, watch pigeons, and then this: “She envied a fat-bellied C-119 cargo plane that roared over the city every other day.” Of all airplanes, both civilian and military, why did Ríos single out a C-119? Is it possible that she was familiar with news coverage of Sister Aquinas’s flight on a C-119 in the summer of 1959? Television’s Flying Nun It did not take long for Hollywood to latch onto the idea of a flying nun for a television series. In early March 1967, ABC announced that its fall line-up would include a series called The Flying Nun, starring Sally Field. The show was described as a “comedy-fantasy.” Today, it would be known as a “sitcom.” Field had earlier starred in a television show about a surfing teenager called “Gidget” that aired for one season. The Flying Nun series ran for three seasons-from September 1967 to April 1970 with a total of 82 episodes. The new show was written and produced by Screen ABOVE: Sally Field, actress, The Flying Nun (ABC) Gems, Inc., and work began on a pilot script LEFT: Tere Rios, 1957, back cover of Brother Angel as early as 1966. I read the second draft of the pilot script that was dated August 18, 1966. I was somewhat taken aback just on the first page of the draft that described the cast. Included in the cast were Carlos who was “one of the richest gamblers and casino operators on the island,” and four named women who were “extremely beautiful young girls” who “worked as dancers in the discotheque owned by Carlos.” Clearly, this television series was not based on Sister Aquinas. Nor, one could argue, on the nun in The Fifteenth Pelican. Understandably, Sister Aquinas was opposed to the title of this new show. She retained an agent who, on March 22, 1967, wrote a lengthy letter to the president of ABC that made this request: “Sir, I respectfully request that you not give your new forthcoming ABC-TV series the title of ‘The Flying Nun.’” [Emphasis in original letter.] After recounting Sister Aquinas’s work over the years being known as the “Flying Nun,” the letter read in part: I am deeply concerned, sir, about ABC using the title of “The Flying Nun,” for a comedy-fantasy show. I feel that such a program will cause damage to my client and subject her title of “The Flying Nun,” to ridicule, thereby negating to a great degree her chances for a motion picture or television show based on her wonderful life which she so much desires at this stage of her life. Credits for Tere Rios books: The Fifteenth Pelican, HFC Archives; and Brother Angel, Wisconsin Historical Society.

HISTORY HANGAR Sister Aquinas at the wheel of a C-119 (HFC Archives) However, in a letter dated February 4, 1971, Ríos asked a retired Air Force colonel, Barney Oldfield, to write a forward for the book. In less than three weeks, he sent her a forward (over three pages long). He had been involved in the award to Sister Aquinas by the Air Force Association back in 1957, and had made the arrangements for her T-33 flight. By March 1972, Sister Aquinas and Tere Ríos were finalizing an agreement between the two of them. In a letter dated March 29, 1972, Ríos’s attorney ended a letter by asking her about her husband’s health: “I also hope that Mr. Versace is satisfactorily recuperating from the heart attack which he had while you were in Florida.” Sadly, Mr. Versace, age 61, died in a hospital in Madison, Wisconsin on June 12, 1972. There would be no biography of Sister Aquinas. By 1974, Tere Ríos had donated her papers and materials to the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, now referred to as the “Tere Ríos Versace Papers.” In addition to correspondence, the collection includes the tapes made by Sister Aquinas and the film of the CBS television show. Those are the same materials I listened to and watched in Madison in March this year. The papers do not have any drafts of any writings on Sister Aquinas. By 1975, Ríos had left Black Earth to work in Guam as a reporter. The letter had no effect, but at least Sister Aquinas and her agent tried. Somewhat surprisingly, the credits at the end of the pilot reveal that the show had received technical assistance from the National Catholic Office of Radio and Television. In her 2018 book, In Pieces, Sally Field wrote that the series was “all gibberish” and “meaningless twaddle with nothing real to relate to.” When one mentions the Flying Nun today, it is the television show that comes to mind. Part III Possible Biography? Although the written record is far from complete, Tere Ríos and Sister Aquinas began communicating around 1971 about the possibility of Ríos writing a biography of Sister Aquinas. In an undated letter to Sister Aquinas, Ríos wrote “Yes, I was so excited to hear from you — and yes, I would be delighted to try if my style will suit you.” She described her style as “lightheaded,” but she probably meant to write “light-hearted.” In an apparent reference to Sister Aquinas’s objection to the title of the television series, Ríos wrote: I was horrified when your friend wrote me that you had planned to use that title, and tried to stop it, but it was too late: all the publicity was out. They were afraid to use The Fifteenth Pelican for fear people would think it was a program about birds, and the Flying Nun simply described the program. Sister Aquinas gave Ríos names of people to contact. In a letter to one of them on March 1971, she wrote: “I am writing the biography of Sister Mary Aquinas…,” and mentioned that she had “reams of material” on Sister Aquinas that included “six tapes she [Sister Aquinas] made herself” and “a one-hour documentary CBS did on her.” There is no record of any response. Holy Family Convent (HFC press release) Sister Aquinas’s final assignment was back at her childhood parish (St. Nicholas) in Zanesville, Ohio from 1971-1977. In 1977, she suffered a stroke and returned to the Holy Family Convent in Manitowoc where she passed away in 1985 at the age of 91. Her contribution to what she called “air-age education” was immense, propelling her to national fame for decades as The Flying Nun. It is sad, indeed, that her fame was eclipsed by the “meaningless twaddle” of a 1960s Hollywood sitcom. Acknowledgments I would like to thank the following people: (1) Sister Caritas Strodthoff, O.S.F., Archivist, Holy Family Convent, for compiling records for my review at the Motherhouse; (2 ) Amanda Smith, Arik Kriha, and Jennifer Barth at the Wisconsin Historical Society during my three days there; (3) Brandi Marulli, The Catholic University of America Archive; and (4) Chiquita Wood, Air Force Magazine. 15 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2020

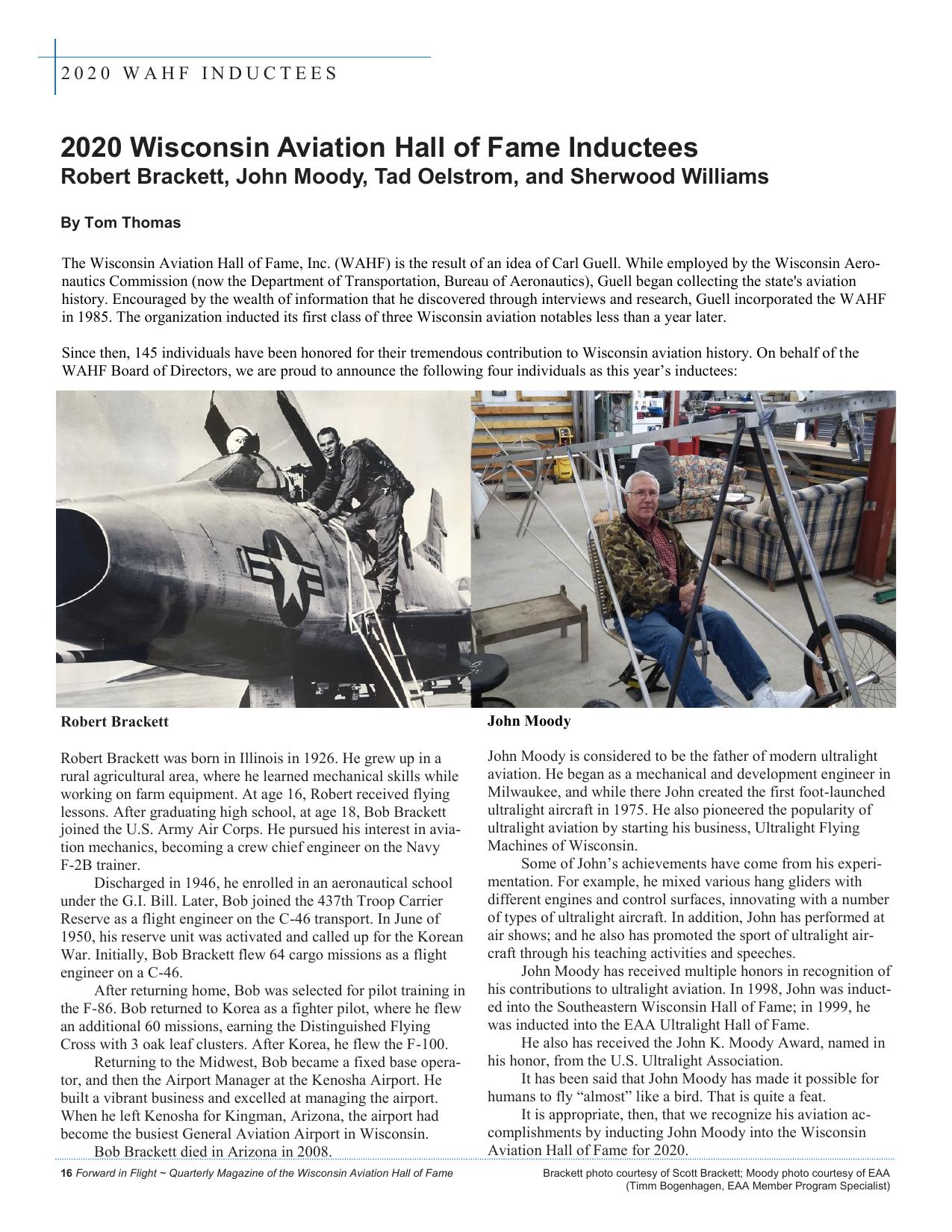

2020 WAHF INDUCTEES 2020 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Inductees Robert Brackett, John Moody, Tad Oelstrom, and Sherwood Williams By Tom Thomas The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame, Inc. (WAHF) is the result of an idea of Carl Guell. While employed by the Wisconsin Aeronautics Commission (now the Department of Transportation, Bureau of Aeronautics), Guell began collecting the state's aviation history. Encouraged by the wealth of information that he discovered through interviews and research, Guell incorporated the WAHF in 1985. The organization inducted its first class of three Wisconsin aviation notables less than a year later. Since then, 145 individuals have been honored for their tremendous contribution to Wisconsin aviation history. On behalf of the WAHF Board of Directors, we are proud to announce the following four individuals as this year’s inductees: Robert Brackett John Moody Robert Brackett was born in Illinois in 1926. He grew up in a rural agricultural area, where he learned mechanical skills while working on farm equipment. At age 16, Robert received flying lessons. After graduating high school, at age 18, Bob Brackett joined the U.S. Army Air Corps. He pursued his interest in aviation mechanics, becoming a crew chief engineer on the Navy F-2B trainer. Discharged in 1946, he enrolled in an aeronautical school under the G.I. Bill. Later, Bob joined the 437th Troop Carrier Reserve as a flight engineer on the C-46 transport. In June of 1950, his reserve unit was activated and called up for the Korean War. Initially, Bob Brackett flew 64 cargo missions as a flight engineer on a C-46. After returning home, Bob was selected for pilot training in the F-86. Bob returned to Korea as a fighter pilot, where he flew an additional 60 missions, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross with 3 oak leaf clusters. After Korea, he flew the F-100. Returning to the Midwest, Bob became a fixed base operator, and then the Airport Manager at the Kenosha Airport. He built a vibrant business and excelled at managing the airport. When he left Kenosha for Kingman, Arizona, the airport had become the busiest General Aviation Airport in Wisconsin. Bob Brackett died in Arizona in 2008. John Moody is considered to be the father of modern ultralight aviation. He began as a mechanical and development engineer in Milwaukee, and while there John created the first foot-launched ultralight aircraft in 1975. He also pioneered the popularity of ultralight aviation by starting his business, Ultralight Flying Machines of Wisconsin. Some of John’s achievements have come from his experimentation. For example, he mixed various hang gliders with different engines and control surfaces, innovating with a number of types of ultralight aircraft. In addition, John has performed at air shows; and he also has promoted the sport of ultralight aircraft through his teaching activities and speeches. John Moody has received multiple honors in recognition of his contributions to ultralight aviation. In 1998, John was inducted into the Southeastern Wisconsin Hall of Fame; in 1999, he was inducted into the EAA Ultralight Hall of Fame. He also has received the John K. Moody Award, named in his honor, from the U.S. Ultralight Association. It has been said that John Moody has made it possible for humans to fly “almost” like a bird. That is quite a feat. It is appropriate, then, that we recognize his aviation accomplishments by inducting John Moody into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame for 2020. 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Brackett photo courtesy of Scott Brackett; Moody photo courtesy of EAA (Timm Bogenhagen, EAA Member Program Specialist)

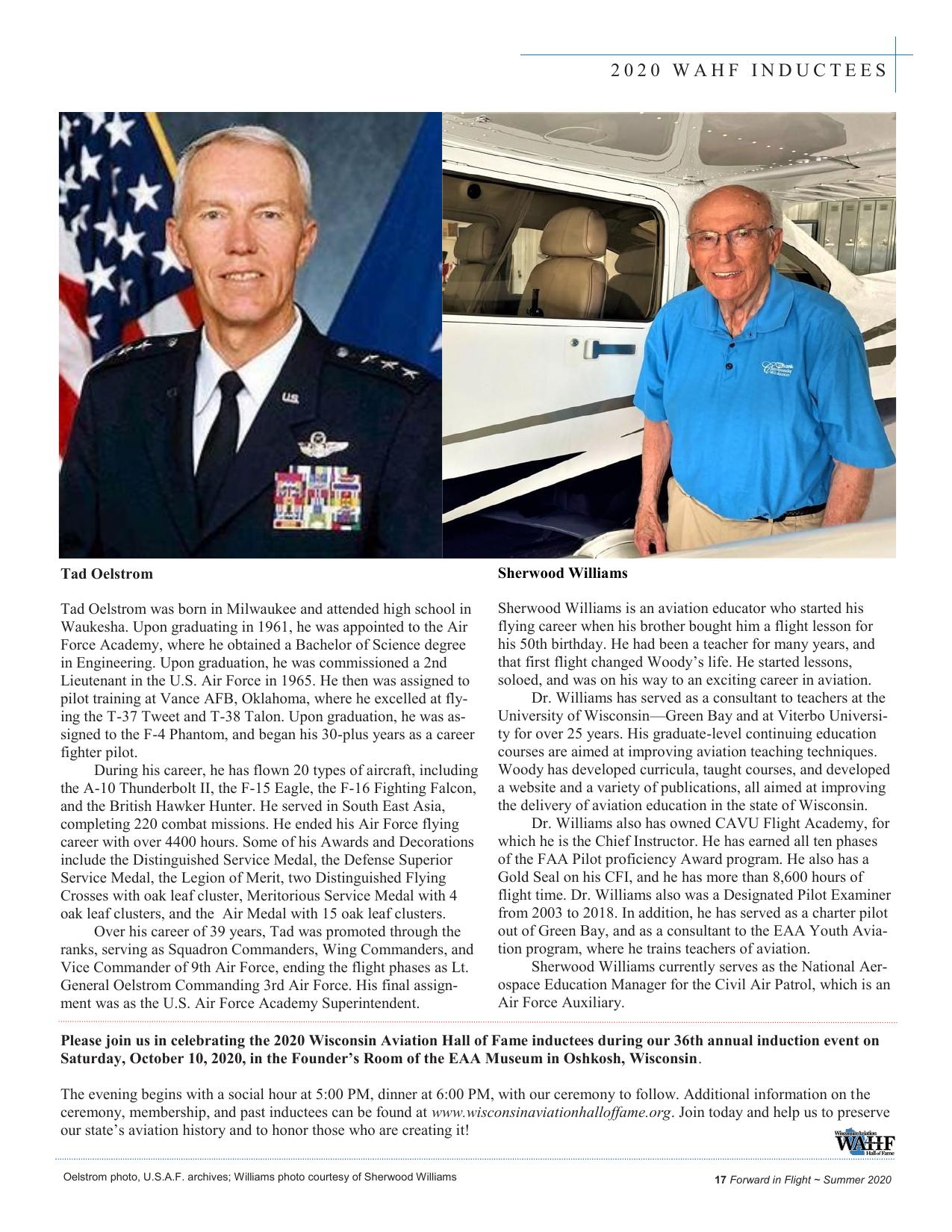

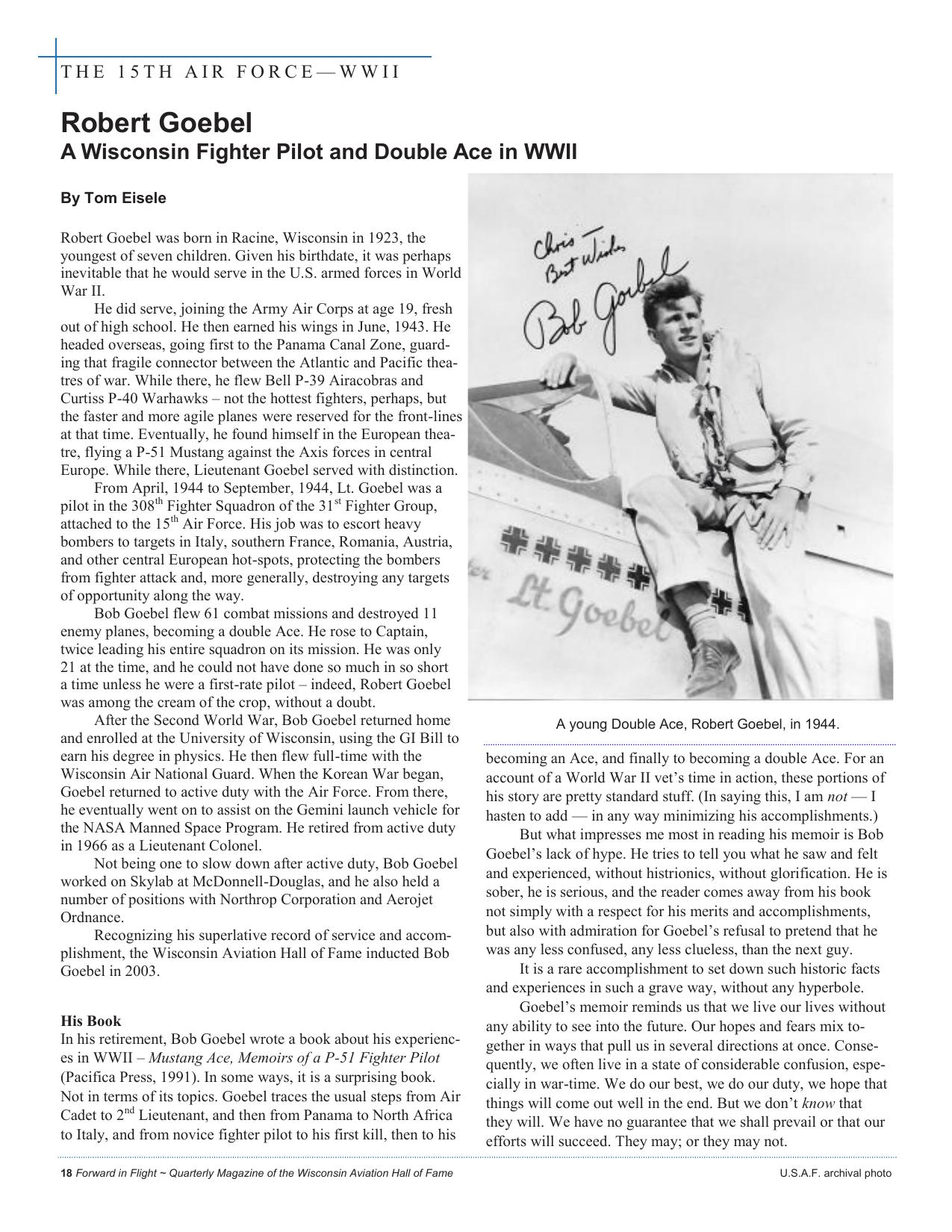

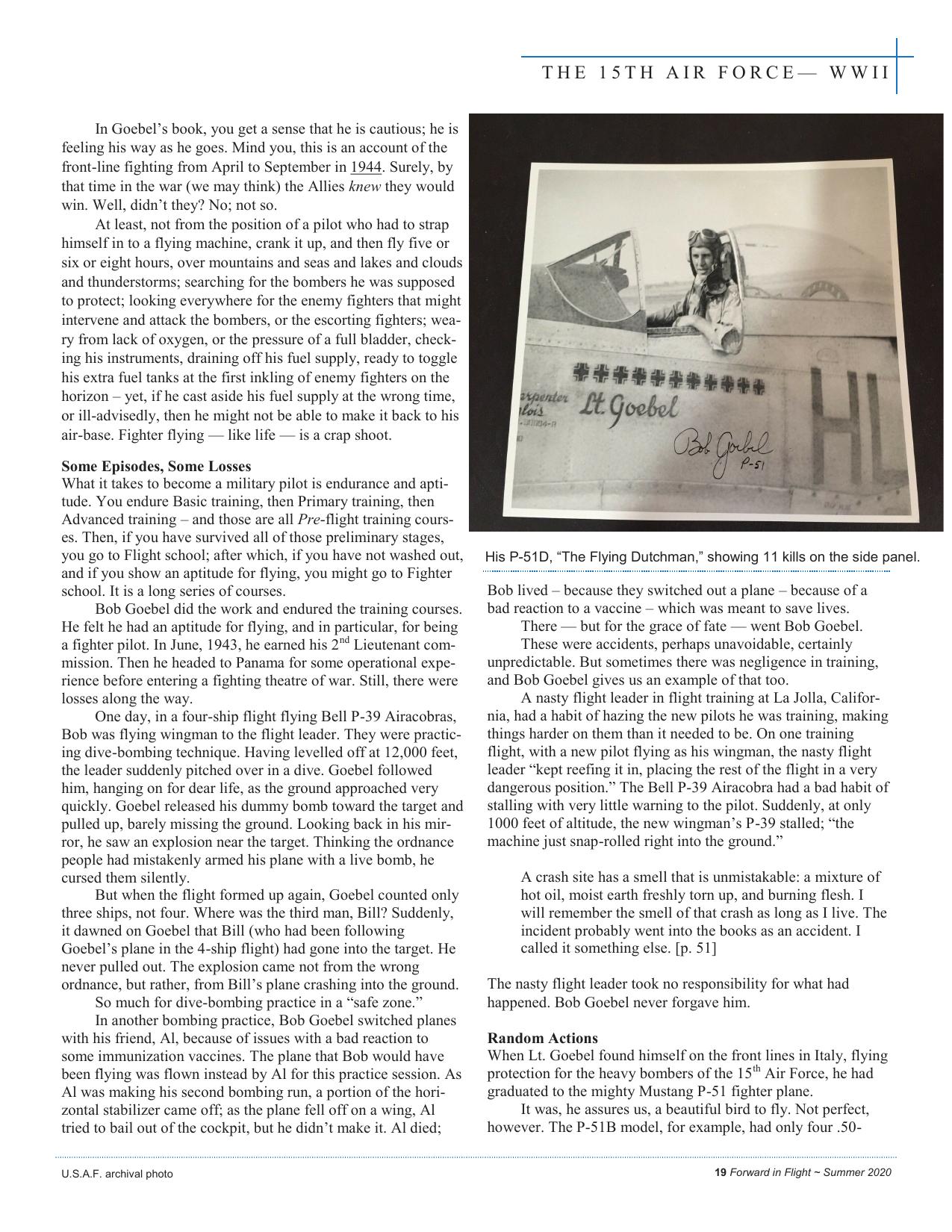

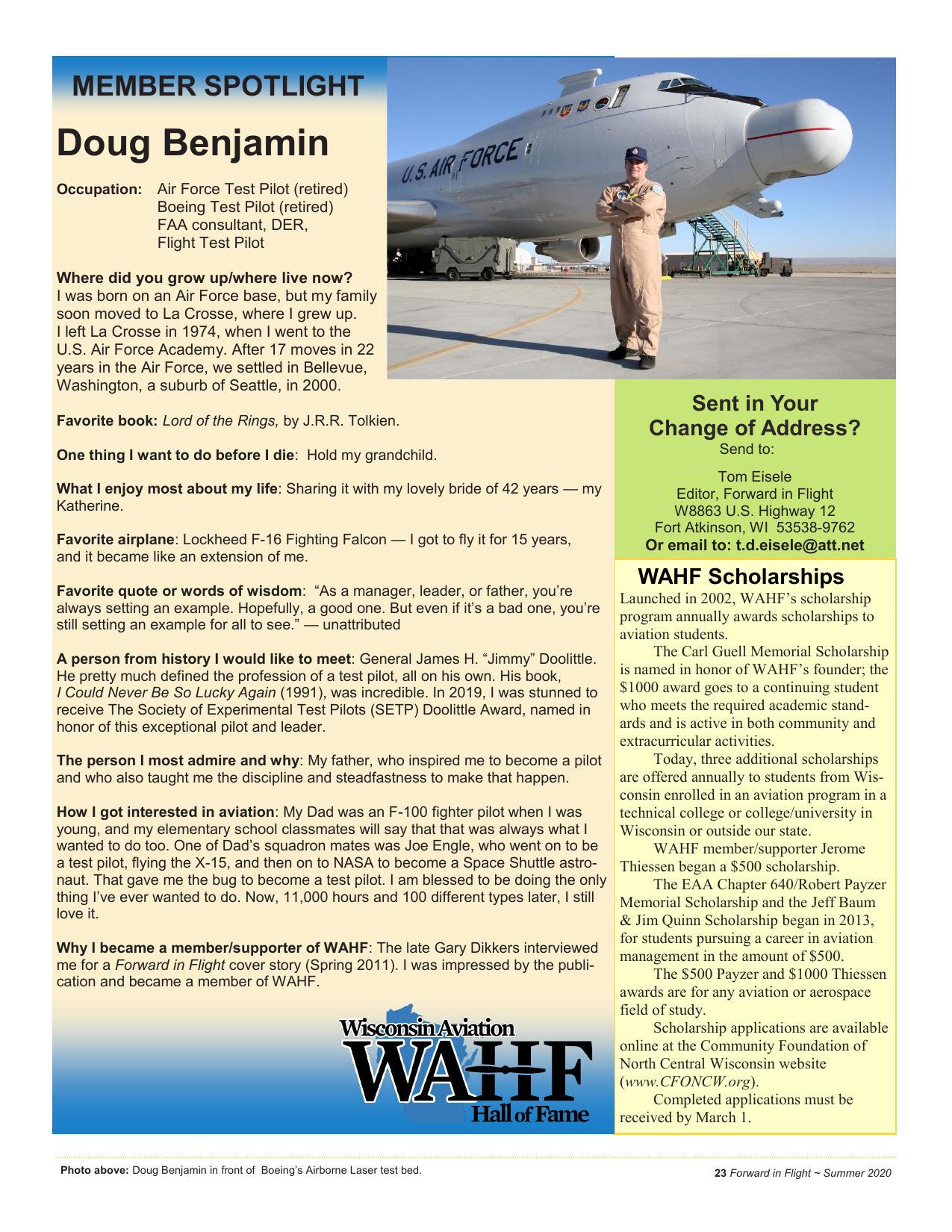

2020 WAHF INDUCTEES Tad Oelstrom Sherwood Williams Tad Oelstrom was born in Milwaukee and attended high school in Waukesha. Upon graduating in 1961, he was appointed to the Air Force Academy, where he obtained a Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering. Upon graduation, he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force in 1965. He then was assigned to pilot training at Vance AFB, Oklahoma, where he excelled at flying the T-37 Tweet and T-38 Talon. Upon graduation, he was assigned to the F-4 Phantom, and began his 30-plus years as a career fighter pilot. During his career, he has flown 20 types of aircraft, including the A-10 Thunderbolt II, the F-15 Eagle, the F-16 Fighting Falcon, and the British Hawker Hunter. He served in South East Asia, completing 220 combat missions. He ended his Air Force flying career with over 4400 hours. Some of his Awards and Decorations include the Distinguished Service Medal, the Defense Superior Service Medal, the Legion of Merit, two Distinguished Flying Crosses with oak leaf cluster, Meritorious Service Medal with 4 oak leaf clusters, and the Air Medal with 15 oak leaf clusters. Over his career of 39 years, Tad was promoted through the ranks, serving as Squadron Commanders, Wing Commanders, and Vice Commander of 9th Air Force, ending the flight phases as Lt. General Oelstrom Commanding 3rd Air Force. His final assignment was as the U.S. Air Force Academy Superintendent. Sherwood Williams is an aviation educator who started his flying career when his brother bought him a flight lesson for his 50th birthday. He had been a teacher for many years, and that first flight changed Woody’s life. He started lessons, soloed, and was on his way to an exciting career in aviation. Dr. Williams has served as a consultant to teachers at the University of Wisconsin—Green Bay and at Viterbo University for over 25 years. His graduate-level continuing education courses are aimed at improving aviation teaching techniques. Woody has developed curricula, taught courses, and developed a website and a variety of publications, all aimed at improving the delivery of aviation education in the state of Wisconsin. Dr. Williams also has owned CAVU Flight Academy, for which he is the Chief Instructor. He has earned all ten phases of the FAA Pilot proficiency Award program. He also has a Gold Seal on his CFI, and he has more than 8,600 hours of flight time. Dr. Williams also was a Designated Pilot Examiner from 2003 to 2018. In addition, he has served as a charter pilot out of Green Bay, and as a consultant to the EAA Youth Aviation program, where he trains teachers of aviation. Sherwood Williams currently serves as the National Aerospace Education Manager for the Civil Air Patrol, which is an Air Force Auxiliary. Please join us in celebrating the 2020 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame inductees during our 36th annual induction event on Saturday, October 10, 2020, in the Founder’s Room of the EAA Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The evening begins with a social hour at 5:00 PM, dinner at 6:00 PM, with our ceremony to follow. Additional information on the ceremony, membership, and past inductees can be found at www.wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org. Join today and help us to preserve our state’s aviation history and to honor those who are creating it! Oelstrom photo, U.S.A.F. archives; Williams photo courtesy of Sherwood Williams 17 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2020