Forward in Flight - Winter 2016

Volume 14, Issue 4 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame WAHF Inducts Five History makers honored Green Bay’s Record Aviation, not football Pistons to Jets Baker, a two war pilot Winter 2016

Contents Vol. 14 Issue 4/Winter 2016 A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame FLIGHT LOGS 2 Fun and Really Fun Takeoffs in summer and winter Elaine Kauh, CFI WE FLY 12 Full On Commitment In everything she does Duane Esse MEDICAL MATTERS 4 The HIMS and FAA-SIRI Program What the acronyms mean Dr. Reid Sousek, AME AVIATION ROOTS 16 Flying Two Wars and a Desk Merton Baker John Dorcey RIGHT SEAT DIARIES 6 Eight Things a Student Pilot Should Know Stay focused on your goal Dr. Heather Monthie TALESPINS 18 Milwaukee KC-135 Visits Madison Tom “Talespin” Thomas FROM THE ARCHIVES 8 The Green Bay File Michael Goc BOOK REVIEW 11 Fighters! John Dorcey GUEST AUTHOR 20 KIA Major John C. Nelson ASSOCIATION NEWS 22 WAHF Inducts Five at Annual Banquet MEMBER SPOTLIGHT 28 Mark Wrasse Duane Esse has been a fixture in aviation, and in the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame, for decades, but Jerry LeBarron’s feature will help you learn much more about Duane's career and what he’s doing these days. Photo courtesy of Roger Hamilton.

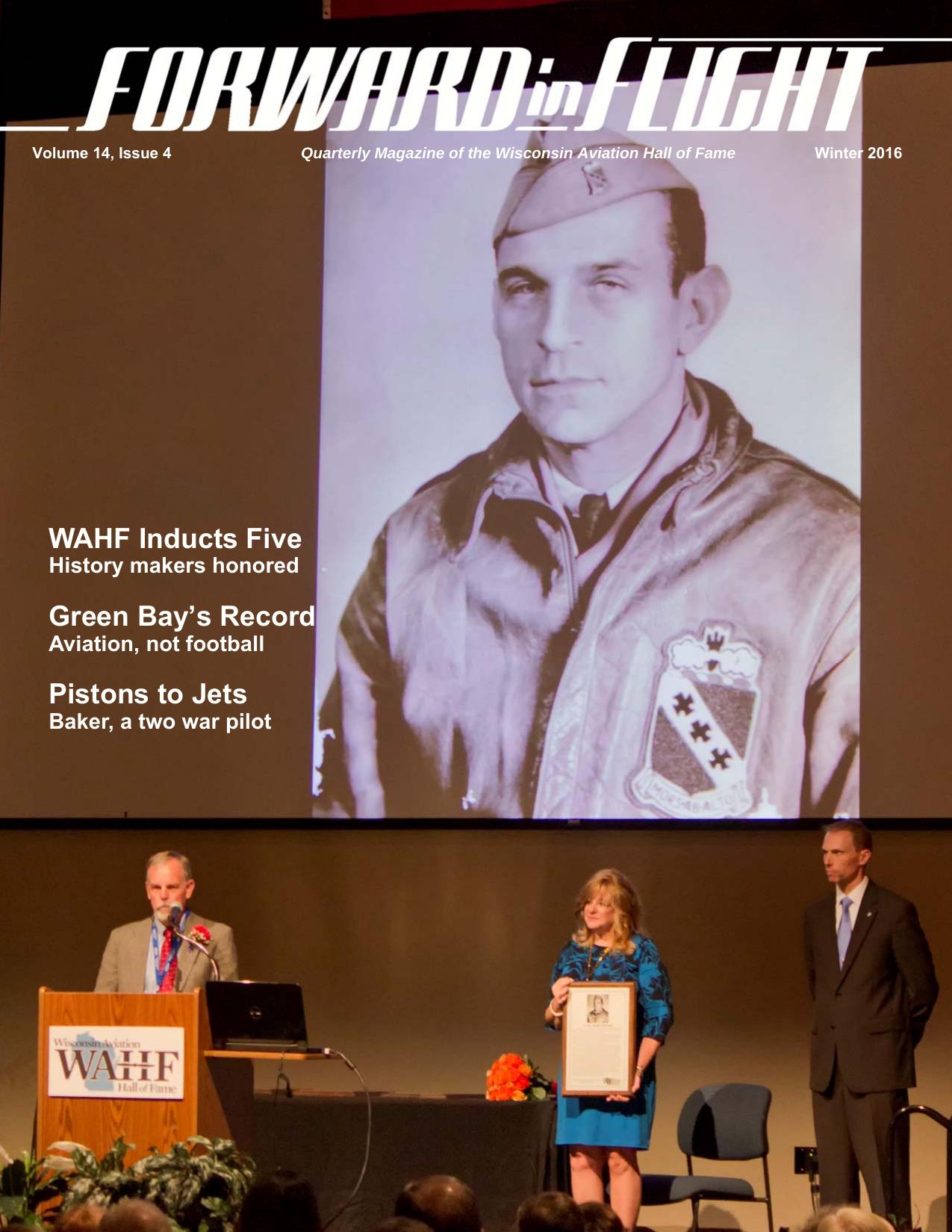

President’s Message By Tom Thomas It was truly humbling and an honor to be elected as the followon president of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Board of Directors at the annual meeting on October 15. Rose Dorcey has served as president for the past 12 years, the longest serving president since the board was established in 1985. WAHF has seen many significant improvements under Rose’s leadership and we’re all pleased that she’s staying on as editor of Forward in Flight magazine. Our mission has stayed on course and with new tools, an enthusiastic board, and WAHF members at large, our flight plan is on file. With the conclusion of this year’s induction ceremony we’ve been cleared for takeoff. My dream of flight has been a lifelong quest. The stories I heard about my three uncles serving in the Army Air Corps in WWII sparked my imagination. In my youth, we lived only four miles from the Madison airport with military and civilian aircraft flying overhead daily, and they kept my eyes skyward. Jumping ahead to 1964, I began flying lessons at Morey Airport with my first flight in December. Field Morey was my instructor and signed me off on March 25, 1965 in a Cessna 150. On March 30, 1965 was a checkout in a C-172, and I’m still flying 172s, now with the UW Flying Club out of Wisconsin Aviation’s East Ramp at Dane County Airport in Madison. In June of 1966, I was commissioned through Air Force ROTC in the USAF and sent to Reese AFB in Lubbock, Texas, for pilot training. Upon graduation actively flew in the Strategic Air Command (SAC) until my commitment was completed in the fall of 1971. Upon returning to Madison and looking for employment, the City of Madison hired me in January 1972 in its Planning Department. At the same time, I enlisted in the Wisconsin Air National Guard Unit in Milwaukee flying the KC97L Stratotankers. Actively flying with the Milwaukee and Madison Guard units blended in well with my flying future. In the fall of 1972, the State Division of Aeronautics advertised for aviation consultants, which was the beginning of a 31-year carrier with the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, flying all over the state. A lot of air has passed over my wings since receiving my private in 1965. Airplanes have taken me across the state, to each coast, and I’ve flown across both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Airplanes are time machines. A month ago when researching some data from the ’70s, a survey of some 40 General Aviation airports in Wisconsin comForward in Flight The only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s events. Rose Dorcey, editor 3980 Sharratt Drive Oshkosh, WI 54901-1276 Phone 920-279-6029 rdorcey@wisconsinaviationhallofame.org The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. piled in 1976 popped up. The Bureau of Airport Operations at the time was responsible for collecting the data and it’s interesting to compare it to where we are today. In 1976, 100/130 avgas averaged 79 cents per gallon, the price of jet fuel averaged 64.5 cents per gallon and oil averaged 90 cents per quart. The comparison for tie downs and hangar rents were also considerably lower than we have now. How times have changed in 40 years! In the 1980s, work began on compiling the history of aviation in Wisconsin by Carl Guell. In 1985, a committee was selected to work on compiling data for Wisconsin’s aviation history book. Duane Esse and I were assigned to the history book committee and I also worked as a Bureau rep to the WAHF Board providing support and historical information on Wisconsin’s airport system and ‘the players’ over the years. Since beginning the task, it has continued to the present in one form or another. I retired from the Bureau of Aeronautics in 2005 and was elected to the WAHF Board of Directors in 2008. I’ve also been actively flying with the UW Flying Club since the early ’90s and currently serve on the UW Flying Club Board of Directors. This also includes working as a part-time flight instructor for Jeff Baum’s Wisconsin Aviation at Dane County Regional Airport (KMSN) in Madison. I look forward to working with the current WAHF board and fulfilling WAHF’s mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. On the cover: WAHF Board Member Kurt Stanich (right) presented Green Bay native Austin Straubel’s induction at the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame’s 31st annual induction ceremony earlier this year in Oshkosh. Aviation history researcher John Dodds accepted Straubel’s plaque (as shown at lectern.) Dodds then presented the plaque to Tom Miller, Executive Director of Green Bay Austin Straubel International Airport (KGRB), where the plaque will be on display. The airport will also feature additional material that will reflect on Straubel’s military career. Watch for more information in a future issue of Forward in Flight. Photo by Jennifer Bowen

FLIGHT LOGS Fun and Really Fun Takeoffs in summer and winter By Elaine Kauh It happens every fall. Just as the leaves start to get that tint of color, we get a crisp, clear day and it’s time to enjoy what I call the Really Fun Takeoffs. All takeoffs are fun, of course, but these are special. That’s when a cooler morning – around 45 to 50 degrees – dramatically changes an airplane’s takeoff performance after months of relatively sluggish departures in the steamy summer months. The fun part of the Really Fun Takeoff is hearing a student, who learned to take off and land over the summer, say “wow” as our little Cessna seems to leap off the runway and climb as if it was a much more powerful airplane. And my pilot is using the same airspeeds as always to take off and climb, yet there’s more runway ahead after liftoff, and the ground falls away quickly, as if an updraft just decided to swoop in underneath and push us up from below. The vertical speed gauge, which usually can’t go beyond 300 to 400 feet per minute on a hot summer day, reads double that during the Really Fun Takeoff. This is more than fun. It’s a dramatic, memorable learning experience that turns airplane performance numbers (not so exciting) into a real flight (really exciting). From an educational standpoint, the contrasts in temperatures throughout the four seasons make for great lessons on airplane performance, one of the major topics we tackle when teaching new pilots. As a cold-weather fan (surprising how few there are in Wisconsin), I must admit I enjoy the relief of not having to climb into a baking cockpit and waiting until we’re a few thousand feet up to cool off. But more importantly, there’s a safety aspect, the true reason we must understand performance and treat it as a collection of bits of useful information, padded with experience, that will keep us out of trouble during takeoffs and landings. That’s why that sensation of a highperformance takeoff is also reassuring. When the airplane is given the atmospheric conditions to perform at its best, or closer to it, safety margins grow fatter. The sooner you can put air between you and the ground and gain altitude, the more options you have should there be a problem with the engine or propeller, which are working at maximum during takeoff. It’s important to pay close attention to any sign of a problem during that critical window of 0 feet at liftoff to about 500 feet (sometimes higher), because it’s risky to be forced into an emergency landing that close to the ground, especially where there aren’t many good places right in front of you to aim for. I like to approach performance as a checklist of hard numbers (calculating performance using an airplane manual’s tables) and more real-life ideas (anticipating what the takeoff/landing will be like). One of the challenges to teaching performance is that the hard numbers only account for certain known weather conditions but never account for everything, and so after taking several minutes with a calculator finding that magic “takeoff roll” figure, you’re only half done and must figure out how to pad that with a safety margin that can only make assumptions for covering the unknowns. Combining exact numbers with imprecise “safety margin” numbers is an exercise in contradictions, but that is how it must be done. As I summed up in a recent safety article, all aircraft performance— everything that characterizes its takeoffs, cruise, and landings—starts with the temperature and pressure of the air it’s flying in. Gather that information before you do anything else and you’re on your way to putting that puzzle together. Air that is “warmer” (we use 60 Fahrenheit as an average) tends to spread out more thinly; we call it “less dense.” Colder air is “more dense,” which gives us a way to know early on if our wings will have “less” or “more” air to work with. Thinner air gives the wings less work with, simply put, and so it doesn’t lift off as well. Thicker air results in that more positive sensation of the airplane more capably lifting off the ground. When it’s 90 degrees outside, that takeoff will be sluggish, no matter what, and we 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame must know that ahead of time and often make contingency plans. Likewise, air pressure (measured in barometric units) has similar, but less noticeable, effects. High pressure (greater than 29.92 inches of mercury) means thicker air, while low pressure means thinner air. So, with two numbers, temperature and pressure, we go to the airplane’s performance tables and get an estimate of how much runway we’ll need to lift off. These tables usually don’t offer a way to estimate vertical speed, so time in the airplane through the seasons tends to be the best gauge of climb performance. Most small airplanes will take off in well under 800 feet on an average day around here, but because every day is different and locations change, it’s important to “run the numbers” any time something is new, such as a higher elevation, an unpaved runway, or a change in temperatures not experienced before. There’s a “wow” on takeoff, but this time it’s the realization that after a few months of expecting a highperformance takeoff, you’re back to that longer roll, slower climb... Sometimes it takes a discussion of the worst-case scenarios to drive home these ideas. So, we look at examples of hot days far from Wisconsin in say, Arizona, where 100-degree summers are normal. Then we look at the airport elevations there and find that the thinner air, coupled with hot temperatures, means you’ll need double, triple, or even quadruple the space to lift off. The most dangerous part of this is not knowing whether our Skyhawk will ever be able to leave

FLIGHT LOGS on. Get to know your airplane’s takeoff performance and you’ll never be short of runway. the runway or climb at all once it does, and accelerating down a strip at the speed of a car on a highway is not the time to find out the airplane doesn’t have enough air. Sadly, these things have happened. Therefore, even at your average airport in Wisconsin on a typical summer day, we won’t depart in a fuel-laden plane from a short runway, especially with trees or power lines at the other end, unless we’re certain it can be done with a comfortable safety margin. Another concern with performance is the unknown gap between what the aircraft tables show and what really happens. In aircraft manuals, performance tables only account for a few variables in round numbers, and they vary among the different airplane models. So, if you’re flying lighter than the maximum weight, have obstacles of unknown height to clear and gusting, variable winds on a humid summer day, there’s no accurate way to calculate takeoff or landing lengths. In the end, there’s only one realistic way to ensure a safe outcome every time; it’s a combination of increasing the margins by a healthy amount, plus building on experience. When new pilots are learning performance, we run our estimates in different weather conditions using the “book numbers,” then we pad Photo by Elaine Kauh that with a “safety margin” of at least a third, round it up, then we go fly. For a calculated takeoff roll of 700 feet on a cool, calm day from a Wisconsin airport, we’re going to assume we’ll need at least 950 feet, and we might as well make that an even 1,000 to make it easier to estimate what we can expect on a 3,000-foot runway. If we can be reasonably assured we’ll take off (and land) in the first onethird of a given runway, we’ll go fly it. Not only have we rounded up our numbers, we’ve allowed ourselves most of the runway to account for any number of unknown variables, such as humidity (which hurts performance), changing winds, and less-than-perfect takeoff technique. (In fact, we emphasize to everyone that no one will ever have the perfect conditions and takeoff technique the test pilots had when they created those tables.) Now for the fun part: We go fly. While it’s often difficult to measure a takeoff roll, we can get a good idea of how much runway has zoomed by during takeoff by planning certain visual markers, such as the runway intersection a third of the way down, or a taxiway, or even the windsock or another landmark. Some longer runways offer runwayremaining signs to let you know when you have 5,000, 4,000 feet left, and so Once you’ve flown throughout the four seasons around Wisconsin, where airport elevations aren’t too different from one another, you have a decent portfolio of knowledge to draw from to help adjust expectations as the months go by and the weather changes. And you know every spring to beware of that first warm day, when the opposite of what happened in October happens. There’s a “wow” on takeoff, but this time it’s the realization that after a few months of expecting a high-performance takeoff, you’re back to that longer roll, slower climb, and sometimes an eye-opening reminder that this is where the real-world experience really comes into play. After a lot of takeoff practice from familiar runways, using the prescribed airspeeds for consistency, you get to know the airplane’s performance. Then you do the same thing on a warmer day, a windier day, and so on. After a while, you can use that experience to know what you can expect. Should you expect something to be different on a future flight, a shorter runway than you’ve experienced, or a full-weight takeoff, back to the books you go to take a fresh look at the situation. I’m aware that in September or October when that first cold day arrives, most of us dread the signs of approaching winter. But to offset that, we just go flying and enjoy that high-performance takeoff we’ve been craving all summer. And just as the airplane seems eager to leave the ground, it’s reluctant to come back down. Cold, dense air is packed with lift, and so it often takes some coaxing (i.e. shedding power) and perhaps some massaging (deploying extra flaps, if you have them) or other maneuvers to simply get low enough to land on the desired spot on the runway. Flight lessons like these, where the weather’s effects on wings become something you can see and feel, are among the most fun and memorable ones. While the weather always changes, what’s constant is the wing’s love for air. The more the better. Elaine Kauh is a flight instructor and aviation writer who enjoys flying in all seasons around eastern Wisconsin. Email Elaine at: ekauh@wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org 3 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016

MEDICAL MATTERS The HIMS and FAA-SSRI Programs What the acronyms mean Dr. Reid Sousek, AME For my second article, I’ll cover some of what I learned at my recent HIMS training. As any good conference attendee would do, I arrived at the conference room early to secure a nice, back row seat…just like in church. Getting to Denver had been easy; getting home, not so much. The flights home were quite interesting; but since it was at the end of my travel, I’ll keep you in suspense until the end of the article. HIMS is a program that many, even in the aviation world, may not have even heard of. HIMS stands for Human Intervention and Motivation Study. (There is no “HERS” program that I’m aware of.) The HIMS program is designed for treatment and monitoring of pilots with alcohol and drug abuse and dependence illnesses. The HIMS framework allows pilots to enter treatment, follow appropriate monitoring and ongoing treatment requirements and hopefully, return to the cockpit. The program’s success relies on not only the affected pilot but also a peer sponsor, a chief pilot (in airline setting), an Independent Medical Sponsor (IMS) or HIMS-AME, and other supporting individuals. A possible course of events begins with some form of intervention identifying a pilot with a substance abuse issue (32 per cent self-report, 28 per cent DUI, 12 per cent positive random testing). The affected individual is evaluated by a substance abuse professional and enters a minimum 28-day treatment facility. Most treatment facilities follow a “12-step” treatment ideology. Assuming an appropriate “buy-in”, the pilot will be discharged to intensive outpatient treatment and aftercare program. After discharge, most are expected to attend “90 in 90” (a minimum of 90 Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in 90 days). Over the next few months, as sobriety is maintained and further recovery stabilizes the pilot, he/she may be ready to undergo in-depth psychological and psychiatric testing and evaluation. The role of the HIMS-AME or IMS is to oversee this testing and monitoring. Over time, when all testing is done and the condition is stable (possibly over a year), the case is then ready to be submitted to the FAA. Simply putting in time or waiting will not lead to progression through the program. The FAA psychiatrist will thoroughly review all office notes, treatment records, AA attendance logs, and any other available info. At that point, a special issuance may be given by the FAA. This special issuance will outline very clearly what ongoing monitoring and follow-up is needed. It is not “alcoholwasm” but rather “alcoholism.” Therefore, the 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame special issuance is not an endpoint, but rather a starting point to return to flying. Over the next few years, an extensive monitoring program is continued and frequent re-evaluations are completed. Absolute sobriety is essential. One measure of the success of the HIMS program is relapse rates, which are much lower for participants of the HIMS program than most other treatment/ monitoring programs. Documented sobriety rates of 85 per cent occur versus 10-30 per cent in programs of other types or for other professions. Confirming ongoing sobriety is based on peer observation and clinical testing. For example, a device called Soberlink, analogous to a breathalyzer, takes a picture of the individual doing the test and submits results real time over cellular networks to the appropriate monitor. Therefore, the monitoring provider gets real-time data and confirmation of sobriety. This may be done twice daily and combined with hair, nail, and blood testing to confirm sobriety. The frequency and type of testing may vary over the years of the monitoring period. The HIMS program is not cheap. An airline that sponsors one of their pilots is not doing it purely out of altruism. United Airlines’ cost analysis shows that it is ultimately more cost effective to support a pilot in this program than to fire and hire someone new. Not only do they do the right thing morally, they also retain a highly trained individual and see lower costs over the remaining career of that pilot. Just over a quarter of pilots may enter a program like this due to a DUI. However, though you must report a DUI to the FAA, just because you are a pilot and get a DUI does not mean you will be required to enter an intensive program like HIMS. Failure to comply with reporting requirements may result in denial of application or revocation/suspension of any current certificate or rating. Ignoring the reporting requirement or just not disclosing is a poor choice. Any one carrying a medical cer- Storm clouds in Dr. Sousek’s flight path. Next page: Minneapolis to Appleton via western Minnesota.

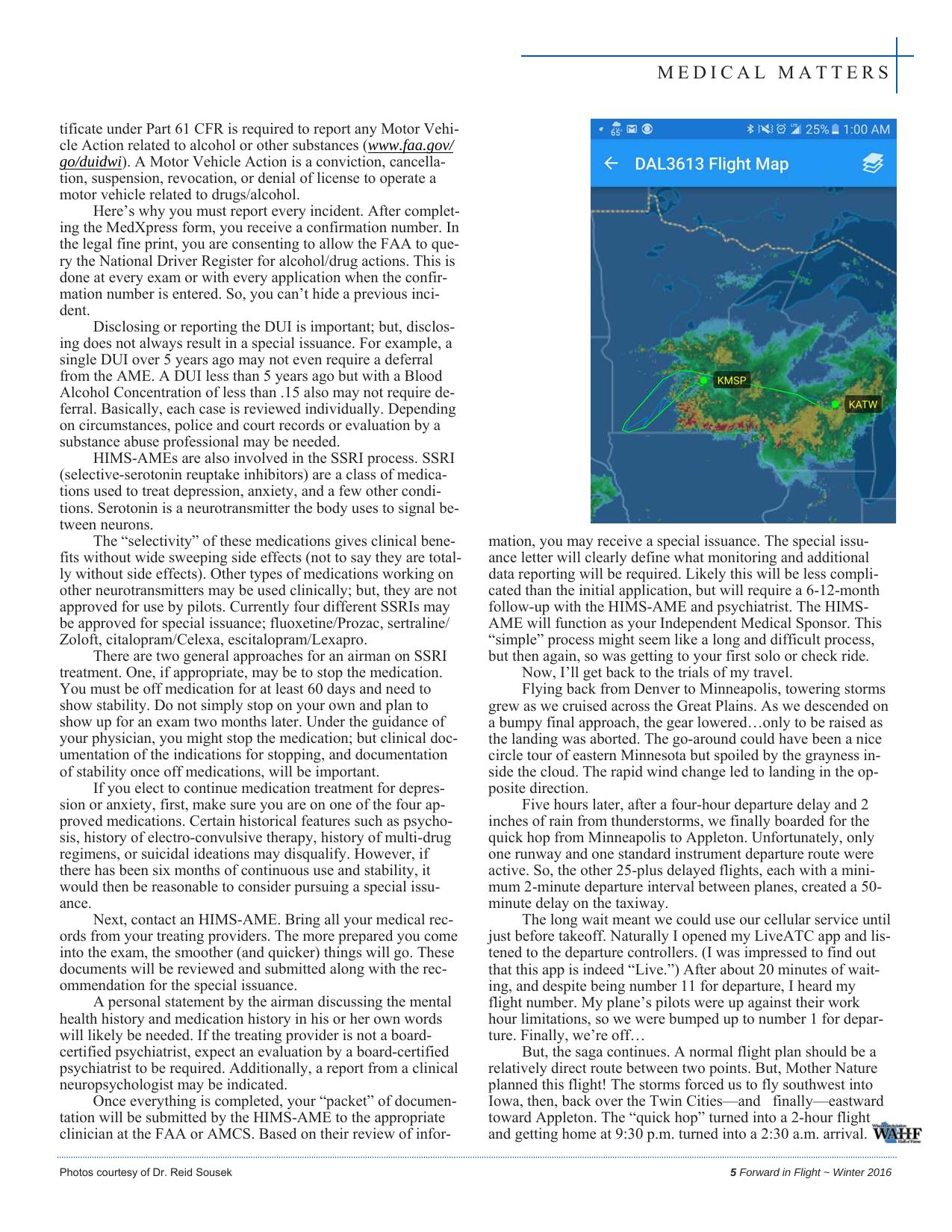

MEDICAL MATTERS tificate under Part 61 CFR is required to report any Motor Vehicle Action related to alcohol or other substances (www.faa.gov/ go/duidwi). A Motor Vehicle Action is a conviction, cancellation, suspension, revocation, or denial of license to operate a motor vehicle related to drugs/alcohol. Here’s why you must report every incident. After completing the MedXpress form, you receive a confirmation number. In the legal fine print, you are consenting to allow the FAA to query the National Driver Register for alcohol/drug actions. This is done at every exam or with every application when the confirmation number is entered. So, you can’t hide a previous incident. Disclosing or reporting the DUI is important; but, disclosing does not always result in a special issuance. For example, a single DUI over 5 years ago may not even require a deferral from the AME. A DUI less than 5 years ago but with a Blood Alcohol Concentration of less than .15 also may not require deferral. Basically, each case is reviewed individually. Depending on circumstances, police and court records or evaluation by a substance abuse professional may be needed. HIMS-AMEs are also involved in the SSRI process. SSRI (selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are a class of medications used to treat depression, anxiety, and a few other conditions. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter the body uses to signal between neurons. The “selectivity” of these medications gives clinical benefits without wide sweeping side effects (not to say they are totally without side effects). Other types of medications working on other neurotransmitters may be used clinically; but, they are not approved for use by pilots. Currently four different SSRIs may be approved for special issuance; fluoxetine/Prozac, sertraline/ Zoloft, citalopram/Celexa, escitalopram/Lexapro. There are two general approaches for an airman on SSRI treatment. One, if appropriate, may be to stop the medication. You must be off medication for at least 60 days and need to show stability. Do not simply stop on your own and plan to show up for an exam two months later. Under the guidance of your physician, you might stop the medication; but clinical documentation of the indications for stopping, and documentation of stability once off medications, will be important. If you elect to continue medication treatment for depression or anxiety, first, make sure you are on one of the four approved medications. Certain historical features such as psychosis, history of electro-convulsive therapy, history of multi-drug regimens, or suicidal ideations may disqualify. However, if there has been six months of continuous use and stability, it would then be reasonable to consider pursuing a special issuance. Next, contact an HIMS-AME. Bring all your medical records from your treating providers. The more prepared you come into the exam, the smoother (and quicker) things will go. These documents will be reviewed and submitted along with the recommendation for the special issuance. A personal statement by the airman discussing the mental health history and medication history in his or her own words will likely be needed. If the treating provider is not a boardcertified psychiatrist, expect an evaluation by a board-certified psychiatrist to be required. Additionally, a report from a clinical neuropsychologist may be indicated. Once everything is completed, your “packet” of documentation will be submitted by the HIMS-AME to the appropriate clinician at the FAA or AMCS. Based on their review of inforPhotos courtesy of Dr. Reid Sousek mation, you may receive a special issuance. The special issuance letter will clearly define what monitoring and additional data reporting will be required. Likely this will be less complicated than the initial application, but will require a 6-12-month follow-up with the HIMS-AME and psychiatrist. The HIMSAME will function as your Independent Medical Sponsor. This “simple” process might seem like a long and difficult process, but then again, so was getting to your first solo or check ride. Now, I’ll get back to the trials of my travel. Flying back from Denver to Minneapolis, towering storms grew as we cruised across the Great Plains. As we descended on a bumpy final approach, the gear lowered…only to be raised as the landing was aborted. The go-around could have been a nice circle tour of eastern Minnesota but spoiled by the grayness inside the cloud. The rapid wind change led to landing in the opposite direction. Five hours later, after a four-hour departure delay and 2 inches of rain from thunderstorms, we finally boarded for the quick hop from Minneapolis to Appleton. Unfortunately, only one runway and one standard instrument departure route were active. So, the other 25-plus delayed flights, each with a minimum 2-minute departure interval between planes, created a 50minute delay on the taxiway. The long wait meant we could use our cellular service until just before takeoff. Naturally I opened my LiveATC app and listened to the departure controllers. (I was impressed to find out that this app is indeed “Live.”) After about 20 minutes of waiting, and despite being number 11 for departure, I heard my flight number. My plane’s pilots were up against their work hour limitations, so we were bumped up to number 1 for departure. Finally, we’re off… But, the saga continues. A normal flight plan should be a relatively direct route between two points. But, Mother Nature planned this flight! The storms forced us to fly southwest into Iowa, then, back over the Twin Cities—and finally—eastward toward Appleton. The “quick hop” turned into a 2-hour flight and getting home at 9:30 p.m. turned into a 2:30 a.m. arrival. 5 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES Eight Things a Student Pilot Should Know Focus on your goal By Dr. Heather Monthie When people find out that I know a little bit about aviation, I am normally asked a couple of questions and the conversation is just about always the same. The information forthcoming may be beneficial to those out there who are considering taking the leap and starting flying lessons! Flight Training Expenses Probably the question I am asked the most is “how much does it cost to learn how to fly?” No, it’s certainly not a cheap hobby, but if you plan for some of the expenses you’re better prepared for the cash you’ll need to come up with down the road. My response to this question is usually an explanation that the cost is about the same as buying a decent used car. Of course, there are the upfront costs that people are normally aware of: the cost of the plane and the cost of the instructor. I always suggest having about half of what it’s going to cost you in the bank so that you can fly more regularly. Trying to come up with the money as you go will often put a damper on the frequency that you can fly. And always keep the money in your own bank account. Don’t pay for flight training up front. It happens all too often; flight schools close, instructors bail, etc. Then there’s what I like to call the “hidden costs” of learning to fly. The things that people aren’t usually aware of before chasing the dream of becoming a pilot. Invest in some good equipment. Some items are probably more necessary than others, such as headsets, a nice flight bag, flight planning software, cool looking aviator sunglasses, fuel testers, and more. Some of these items can be expensive, so it’s important to know right away that you’ll probably enjoy spending some money on these kinds of things! Flight Training Takes Time Think of it like a part time job. The second most popular question I am asked about what it takes to learn how to fly is how long it takes. This is a harder question to answer since there are so many variables to consider. You need to take into consideration all the other responsibilities you have going on. Do you have time to take on a part time job? The amount of time you’ll need to dedicate to learning is like having a part-time job. If you’re working 60 hours a week and have an hour commute every day, it’s probably going to take you longer than someone who can devote a couple of hours a day to learning. When I was first learning how to fly, it took me about four months from first flight to checkride. I was 19 years old, was working part-time, didn’t have a mortgage or other major life responsibilities yet. I could dedicate a couple of hours a week to flying and a couple of hours a day were dedicated to ground school and studying. Fast forward to today – I have a career, a commute, I’m a competitive athlete, and have a family with 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame whom I like to spend time. This means I need to divide my time between work, training in the gym, family, and day-to-day responsibilities. Now if I add something like learning to fly into that mix, time management becomes so important. Maybe I can’t spend 2-3 hours a day studying like I could when I was 19, but I could listen to some great audiobooks during my commute to help with studying. You’ve just got to take all the responsibilities in your life into consideration and move those pieces around a bit to add in flight training. You might even conclude that right now is not the best time, but maybe next summer will be. It’s Not Just about Flying the Airplane A couple of weeks ago, I was attending a conference in another city. My Uber driver was telling me about his father-in-law who takes him flying and lets him fly the plane. He lets him take off and fly, but he doesn’t let him land. He told me that he could get his certificate any time. All he needed to do was take the test. Throughout that conversation, I realized he didn’t understand how much more there is to being a good pilot than just knowing how to fly the plane. You will need to know regulations, aerodynamics, aircraft systems, flight planning and navigation, calculating measurements such as fuel use, takeoff distance, and more. Sure, you may know how to fly the plane very well, but if you don’t understand the context of why and how you’re flying the plane then you’re just not ready yet. Which brings me to my next point. Don’t Wait to Start Ground School Some of you reading this may be educators as well. You’re probably aware that there’s this natural tendency for many people to want to just jump right into something and get their hands dirty. In my professional role as an educator, I see students learning technical skills who want to get in and write code or design information systems without first having a solid foundation. Yes, it helps with motivation to do these activities right away but there does come a point where you need to start solidifying foundational knowledge. Don’t wait until you’re well past your first solo to start ground school. A lot of the knowledge areas that you’ll learn in ground school will apply to your actual flight training. It helps to put a lot of sometimes difficult topics into context. A lot of fight schools will offer a ground school in a classroom setting. This is a great idea for anyone who needs the structure of a classroom, such as regular schedule, structured lessons, learning in a group environment, and ability to interact with others who are also learning the same things. Some prefer the self-paced courses and others may prefer one-on-one ground lessons with an instructor. Regardless of enrolling in an official ground

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES school, it’s important to understand that your flight instructor, who is providing the actual flight lessons, is also required to give you formal ground instruction as well. Many people choose to supplement this with additional ground instruction in the formats I described above. Make Sure Your Spouse is Onboard I am not a marriage expert, but it seems to me that taking on a new endeavor is a lot easier when you have the support of your spouse. Some people, myself included, may have started flying before meeting their spouse. Others are bitten by the flying bug after meeting their spouse. Learning to fly takes a lot of time and money. Your spouse may not like the amount of time you’re spending at the airport. Adding flying lessons into your life may not align with some of your financial goals you have as a couple. This past summer in Oshkosh, I spoke to someone who turned down a student once he found out the student was putting all his flying expenses on his credit card and that it was creating tension in his marriage. This instructor felt as though he couldn’t be a part of that stress. I think we’ve all heard about spouses who aren’t supportive of flying but maybe sometimes it’s just rising credit card balances that are creating the tension. Take Care of Your Stuff! Your stuff is expensive. Take care of it and it will last you a long time. This goes for more than just flying obviously! I’ve seen so many airplanes sitting outside, completely run down and seemingly abandoned on a ramp. Pay attention to how you store your headsets so cables last longer. Pay attention to the little details on your airplane. Failure to do so can make those little details into a big deal someday. Stay Grounded You’ve probably heard this joke: How do you know if there’s a pilot in the room? He/She will tell you! Of course, we all love to talk about flying when we are not flying. But this is not a hobby where you want to let your ego drive your decisions. A little humility goes a long way in aviation. You are always learning and can learn something from every aviator you meet, regardless of experience. Staying humble will help keep you out of dangerous situations. Keeping an open mind with everyone you meet will open some great opportunities for you! Keep a Growth Mindset As an educator, I am always keeping an eye on whether someone has a fixed or growth mindset in certain situations, myself included. A fixed mindset is the thought that you can’t change how smart you are. Having thoughts like “maybe I am just not smart enough to do this” or “I’m not good at math” are going to hold you back when learning to fly. Of course, we all have days where we feel like we suck at life. Have your five-minute pity party and move on! A growth mindset is the belief that failure is your chance to learn. Sometimes just having a bit more confidence in your skills makes it easier to have a growth mindset. A study done with Aviation Technology students at Purdue University found that there was a small change in students having less of a fixed mindset by their senior years . Perhaps having a bit more experience and confidence can help shift away from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset. Being prepared for obstacles is part of successful flight training. Things will happen and keeping these things in mind prior to starting will help keep you focused on your end goal! I hope that some of these points clear up questions you may have prior to learning to fly. Maybe you’ll even want to share this with someone you know who is on the fence about starting their flight training. 10 Growth Mindset Statements What can I say to myself? Instead of: I’m not good at this… I’m awesome at this… I give up… This is too hard… I can’t make this any better… I just can’t do math... I made a mistake… She’s so smart, I’ll never be that smart… It’s good enough… Plan “A” didn’t work... Try thinking: What am I missing? I’m on the right track. I’ll use some of the strategies I’ve learned. This may take some time and effort. I can always improve so I'll keep trying. I’m going to train my brain in Math. Mistakes help me to learn better. I’m going to igure out how she does it. Is it really my best work? Good thing the alphabet has 25 more letters. 7 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016

FROM THE ARCHIVES The Green Bay File By Michael Goc After witnessing Kurt Stanich and John Dodds make their fine presentations on Austin Straubel at our last induction banquet on October 15, I resolved to see what our archives contain on the history of aviation in Green Bay. First, I encountered information on a couple of Wisconsin’s earliest homebuilders and pilots. Next came a nice packet of material compiled by local historian Steve Milquet on Alfred Lawson and the investors who backed his venture into military aircraft construction in 1917-’18. We also have a copy of a booklet published in honor of the dedication of the new terminal at “Austin Straubel Field” in 1965 that presents a time-capsule view of aviation in the Green Bay area at the time. Let’s begin with the pioneers. The summer of 1911 saw airplanes making exhibition flights at county fairs and other events throughout Wisconsin. They made an impression in Green Bay. The program for the graduation ceremony at Green Bay High that year was entitled “The Aeroplane.” Aviation was in the air, so to speak and two members of the class of 1911, Harry Tees and Earl Knowland, had inhaled deeply. Tees and Knowland started building an airplane modeled on the popular Curtiss pusher design in the Tees backyard on Walnut Street in Green Bay. They acquired a four-cylinder engine, mounted it behind the pilot seat, fixed a prop and were ready to fly in the summer of 1912—so they thought. They transported the plane to a clearing near the Oak Circle area in Green Bay and prepared for takeoff. Young Harry, who may have seen an airplane in flight once in his life but had had no instruction, was at the controls. As many another pioneer pilot learned, getting a flying machine into the air was the easy part. Landing without breaking your neck was harder. Tees did get into the air and stayed there long enough for his effort to be a flight—not just a hop. He did not break his neck on landing, but did severely damage his airplane. He repaired and reassembled it, made another flight, and crashed again. The damage was serious enough to ground the Tees Flyer. Still interested in aviation, Harry answered an ad for an aircraft mechanic in a magazine placed by an exhibition pilot from Tennessee. He spent the next five years or so on the air exhibition circuit. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, he was drafted into the infantry where he served for the duration, despite his many attempts to convince his superiors that someone with his experience should be in the Air Service. After Tees left Green Bay in 1912, his friend Earl Knowland picked up the pieces of the Tees Flyer and rebuilt it. Perhaps hoping for softer landings, he converted it into a “hydro -aeroplane” by mounting floats on the wings. He made many successful flights off the waters of Green Bay in 1913 before grounding the machine. Tees did not get back in to aviation after World War I. However, his machine was the first airplane we know of that was built entirely in Wisconsin that could actually fly. Wausau’s John Schwister was flying a good year before Tees, but he started building his airplane in Minnesota and only completed it in Wisconsin. That’s why he called it the “Minnesota Badger.” 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Young Harry Tees at the controls of his homebuilt flyer in Green Bay, 1912. Knowland’s redo of Tees’ plane is, as far as we know, the first floatplane built in this state. Knowland was part of the Hoberg papermaking family of Green Bay and young Earl’s experience might have made a difference when Alfred Lawson came to town in the spring of 1917. Energetic and eccentric, Alfred Lawson was well-known as the publisher of aviation periodicals whose pages were filled with illustrations of fanciful aircraft. Lawson claimed to have invented the term, as well as airliner. He saw the imminent American entry into the European war as an opportunity to turn his ideas on aircraft design into reality. He had a plan for a military trainer that he believed was superior to the already established JNs that Glenn Curtiss had introduced in 1914 and was manufacturing in Canada. With the US in the war Curtiss could bring his operation back to this country without violating neutrality laws. Curtiss would soon build the largest airplane factory in the world at Buffalo, New York. Undaunted, Lawson left his headquarters in Philadelphia in search of investors. He tried Chicago and Milwaukee with little success, but had better luck after accepting an invitation to come to Green Bay. “I should like to establish an aeroplane plant in Green Bay for several reasons,” he told the directors of the Green Bay Association of Commerce in March 1917, a few weeks before the American declaration of war. “Green Bay is on the Great Lakes and will permit quick delivery of aircraft to sportsmen…. Many motorboat owners are taking up flying. Railroad facilities permit receiving of material….and shipping of constructed aircraft to all parts of the country.” The Lawson Aircraft Company was incorporated in Wisconsin on April 5, 1917, one day before Congress declared war WAHF Archives photos

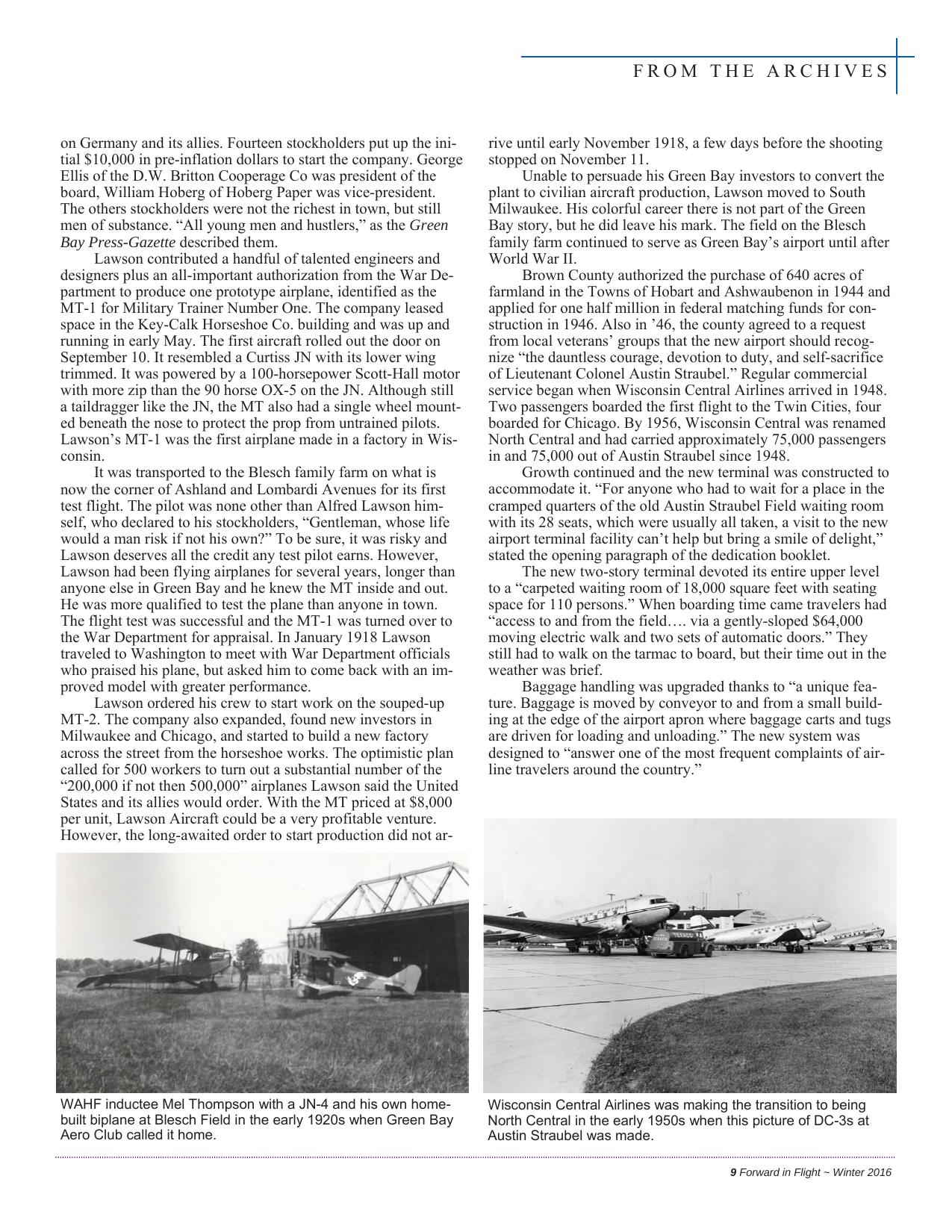

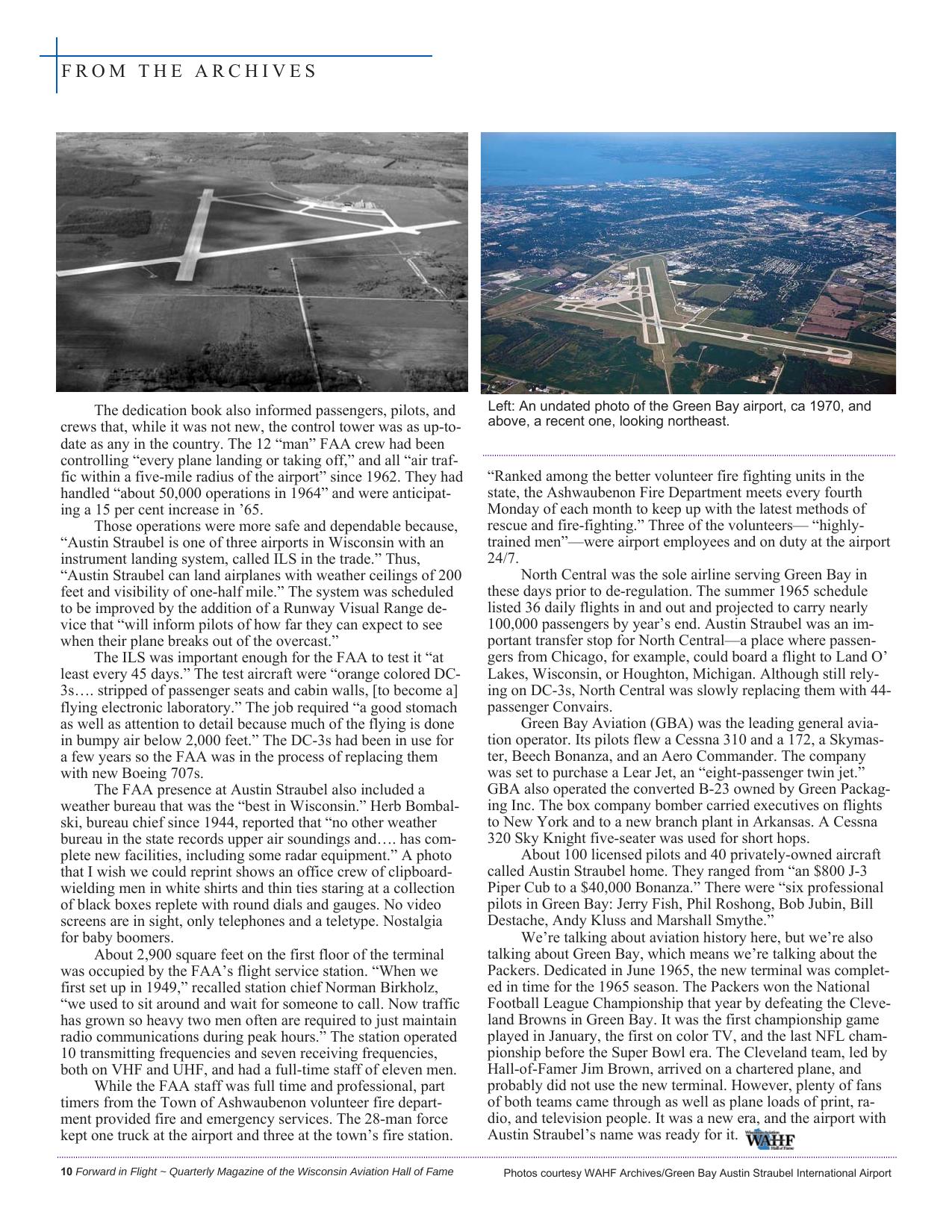

FROM THE ARCHIVES on Germany and its allies. Fourteen stockholders put up the initial $10,000 in pre-inflation dollars to start the company. George Ellis of the D.W. Britton Cooperage Co was president of the board, William Hoberg of Hoberg Paper was vice-president. The others stockholders were not the richest in town, but still men of substance. “All young men and hustlers,” as the Green Bay Press-Gazette described them. Lawson contributed a handful of talented engineers and designers plus an all-important authorization from the War Department to produce one prototype airplane, identified as the MT-1 for Military Trainer Number One. The company leased space in the Key-Calk Horseshoe Co. building and was up and running in early May. The first aircraft rolled out the door on September 10. It resembled a Curtiss JN with its lower wing trimmed. It was powered by a 100-horsepower Scott-Hall motor with more zip than the 90 horse OX-5 on the JN. Although still a taildragger like the JN, the MT also had a single wheel mounted beneath the nose to protect the prop from untrained pilots. Lawson’s MT-1 was the first airplane made in a factory in Wisconsin. It was transported to the Blesch family farm on what is now the corner of Ashland and Lombardi Avenues for its first test flight. The pilot was none other than Alfred Lawson himself, who declared to his stockholders, “Gentleman, whose life would a man risk if not his own?” To be sure, it was risky and Lawson deserves all the credit any test pilot earns. However, Lawson had been flying airplanes for several years, longer than anyone else in Green Bay and he knew the MT inside and out. He was more qualified to test the plane than anyone in town. The flight test was successful and the MT-1 was turned over to the War Department for appraisal. In January 1918 Lawson traveled to Washington to meet with War Department officials who praised his plane, but asked him to come back with an improved model with greater performance. Lawson ordered his crew to start work on the souped-up MT-2. The company also expanded, found new investors in Milwaukee and Chicago, and started to build a new factory across the street from the horseshoe works. The optimistic plan called for 500 workers to turn out a substantial number of the “200,000 if not then 500,000” airplanes Lawson said the United States and its allies would order. With the MT priced at $8,000 per unit, Lawson Aircraft could be a very profitable venture. However, the long-awaited order to start production did not ar- rive until early November 1918, a few days before the shooting stopped on November 11. Unable to persuade his Green Bay investors to convert the plant to civilian aircraft production, Lawson moved to South Milwaukee. His colorful career there is not part of the Green Bay story, but he did leave his mark. The field on the Blesch family farm continued to serve as Green Bay’s airport until after World War II. Brown County authorized the purchase of 640 acres of farmland in the Towns of Hobart and Ashwaubenon in 1944 and applied for one half million in federal matching funds for construction in 1946. Also in ’46, the county agreed to a request from local veterans’ groups that the new airport should recognize “the dauntless courage, devotion to duty, and self-sacrifice of Lieutenant Colonel Austin Straubel.” Regular commercial service began when Wisconsin Central Airlines arrived in 1948. Two passengers boarded the first flight to the Twin Cities, four boarded for Chicago. By 1956, Wisconsin Central was renamed North Central and had carried approximately 75,000 passengers in and 75,000 out of Austin Straubel since 1948. Growth continued and the new terminal was constructed to accommodate it. “For anyone who had to wait for a place in the cramped quarters of the old Austin Straubel Field waiting room with its 28 seats, which were usually all taken, a visit to the new airport terminal facility can’t help but bring a smile of delight,” stated the opening paragraph of the dedication booklet. The new two-story terminal devoted its entire upper level to a “carpeted waiting room of 18,000 square feet with seating space for 110 persons.” When boarding time came travelers had “access to and from the field…. via a gently-sloped $64,000 moving electric walk and two sets of automatic doors.” They still had to walk on the tarmac to board, but their time out in the weather was brief. Baggage handling was upgraded thanks to “a unique feature. Baggage is moved by conveyor to and from a small building at the edge of the airport apron where baggage carts and tugs are driven for loading and unloading.” The new system was designed to “answer one of the most frequent complaints of airline travelers around the country.” WAHF inductee Mel Thompson with a JN-4 and his own homebuilt biplane at Blesch Field in the early 1920s when Green Bay Aero Club called it home. Wisconsin Central Airlines was making the transition to being North Central in the early 1950s when this picture of DC-3s at Austin Straubel was made. 9 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016

FROM THE ARCHIVES The dedication book also informed passengers, pilots, and crews that, while it was not new, the control tower was as up-todate as any in the country. The 12 “man” FAA crew had been controlling “every plane landing or taking off,” and all “air traffic within a five-mile radius of the airport” since 1962. They had handled “about 50,000 operations in 1964” and were anticipating a 15 per cent increase in ’65. Those operations were more safe and dependable because, “Austin Straubel is one of three airports in Wisconsin with an instrument landing system, called ILS in the trade.” Thus, “Austin Straubel can land airplanes with weather ceilings of 200 feet and visibility of one-half mile.” The system was scheduled to be improved by the addition of a Runway Visual Range device that “will inform pilots of how far they can expect to see when their plane breaks out of the overcast.” The ILS was important enough for the FAA to test it “at least every 45 days.” The test aircraft were “orange colored DC3s…. stripped of passenger seats and cabin walls, [to become a] flying electronic laboratory.” The job required “a good stomach as well as attention to detail because much of the flying is done in bumpy air below 2,000 feet.” The DC-3s had been in use for a few years so the FAA was in the process of replacing them with new Boeing 707s. The FAA presence at Austin Straubel also included a weather bureau that was the “best in Wisconsin.” Herb Bombalski, bureau chief since 1944, reported that “no other weather bureau in the state records upper air soundings and…. has complete new facilities, including some radar equipment.” A photo that I wish we could reprint shows an office crew of clipboardwielding men in white shirts and thin ties staring at a collection of black boxes replete with round dials and gauges. No video screens are in sight, only telephones and a teletype. Nostalgia for baby boomers. About 2,900 square feet on the first floor of the terminal was occupied by the FAA’s flight service station. “When we first set up in 1949,” recalled station chief Norman Birkholz, “we used to sit around and wait for someone to call. Now traffic has grown so heavy two men often are required to just maintain radio communications during peak hours.” The station operated 10 transmitting frequencies and seven receiving frequencies, both on VHF and UHF, and had a full-time staff of eleven men. While the FAA staff was full time and professional, part timers from the Town of Ashwaubenon volunteer fire department provided fire and emergency services. The 28-man force kept one truck at the airport and three at the town’s fire station. 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Left: An undated photo of the Green Bay airport, ca 1970, and above, a recent one, looking northeast. “Ranked among the better volunteer fire fighting units in the state, the Ashwaubenon Fire Department meets every fourth Monday of each month to keep up with the latest methods of rescue and fire-fighting.” Three of the volunteers— “highlytrained men”—were airport employees and on duty at the airport 24/7. North Central was the sole airline serving Green Bay in these days prior to de-regulation. The summer 1965 schedule listed 36 daily flights in and out and projected to carry nearly 100,000 passengers by year’s end. Austin Straubel was an important transfer stop for North Central—a place where passengers from Chicago, for example, could board a flight to Land O’ Lakes, Wisconsin, or Houghton, Michigan. Although still relying on DC-3s, North Central was slowly replacing them with 44passenger Convairs. Green Bay Aviation (GBA) was the leading general aviation operator. Its pilots flew a Cessna 310 and a 172, a Skymaster, Beech Bonanza, and an Aero Commander. The company was set to purchase a Lear Jet, an “eight-passenger twin jet.” GBA also operated the converted B-23 owned by Green Packaging Inc. The box company bomber carried executives on flights to New York and to a new branch plant in Arkansas. A Cessna 320 Sky Knight five-seater was used for short hops. About 100 licensed pilots and 40 privately-owned aircraft called Austin Straubel home. They ranged from “an $800 J-3 Piper Cub to a $40,000 Bonanza.” There were “six professional pilots in Green Bay: Jerry Fish, Phil Roshong, Bob Jubin, Bill Destache, Andy Kluss and Marshall Smythe.” We’re talking about aviation history here, but we’re also talking about Green Bay, which means we’re talking about the Packers. Dedicated in June 1965, the new terminal was completed in time for the 1965 season. The Packers won the National Football League Championship that year by defeating the Cleveland Browns in Green Bay. It was the first championship game played in January, the first on color TV, and the last NFL championship before the Super Bowl era. The Cleveland team, led by Hall-of-Famer Jim Brown, arrived on a chartered plane, and probably did not use the new terminal. However, plenty of fans of both teams came through as well as plane loads of print, radio, and television people. It was a new era, and the airport with Austin Straubel’s name was ready for it. Photos courtesy WAHF Archives/Green Bay Austin Straubel International Airport

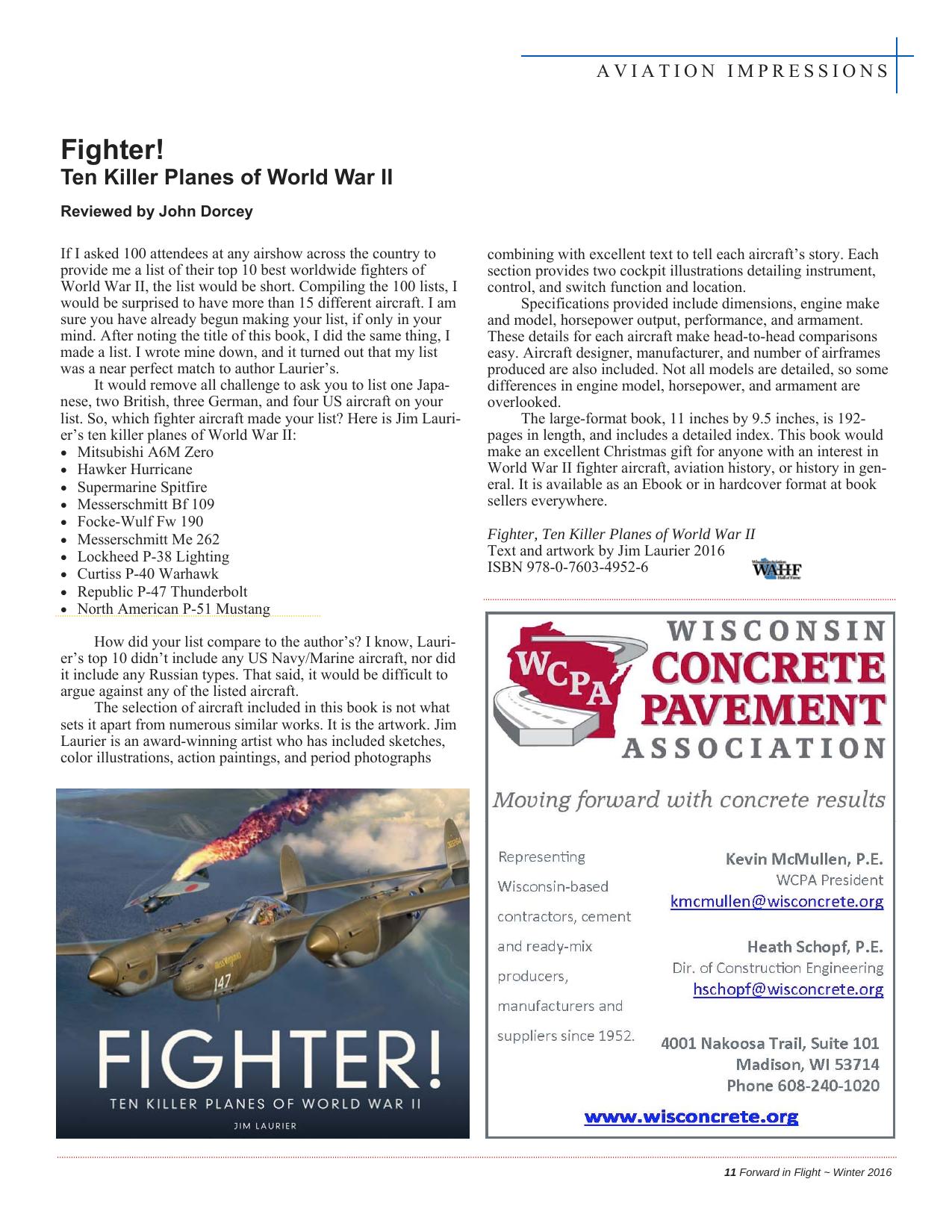

AVIATION IMPRESSIONS Fighter! Ten Killer Planes of World War II Reviewed by John Dorcey If I asked 100 attendees at any airshow across the country to provide me a list of their top 10 best worldwide fighters of World War II, the list would be short. Compiling the 100 lists, I would be surprised to have more than 15 different aircraft. I am sure you have already begun making your list, if only in your mind. After noting the title of this book, I did the same thing, I made a list. I wrote mine down, and it turned out that my list was a near perfect match to author Laurier’s. It would remove all challenge to ask you to list one Japanese, two British, three German, and four US aircraft on your list. So, which fighter aircraft made your list? Here is Jim Laurier’s ten killer planes of World War II: Mitsubishi A6M Zero Hawker Hurricane Supermarine Spitfire Messerschmitt Bf 109 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 Messerschmitt Me 262 Lockheed P-38 Lighting Curtiss P-40 Warhawk Republic P-47 Thunderbolt North American P-51 Mustang combining with excellent text to tell each aircraft’s story. Each section provides two cockpit illustrations detailing instrument, control, and switch function and location. Specifications provided include dimensions, engine make and model, horsepower output, performance, and armament. These details for each aircraft make head-to-head comparisons easy. Aircraft designer, manufacturer, and number of airframes produced are also included. Not all models are detailed, so some differences in engine model, horsepower, and armament are overlooked. The large-format book, 11 inches by 9.5 inches, is 192pages in length, and includes a detailed index. This book would make an excellent Christmas gift for anyone with an interest in World War II fighter aircraft, aviation history, or history in general. It is available as an Ebook or in hardcover format at book sellers everywhere. Fighter, Ten Killer Planes of World War II Text and artwork by Jim Laurier 2016 ISBN 978-0-7603-4952-6 How did your list compare to the author’s? I know, Laurier’s top 10 didn’t include any US Navy/Marine aircraft, nor did it include any Russian types. That said, it would be difficult to argue against any of the listed aircraft. The selection of aircraft included in this book is not what sets it apart from numerous similar works. It is the artwork. Jim Laurier is an award-winning artist who has included sketches, color illustrations, action paintings, and period photographs 11 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016

WE FLY Full On Commitment In everything she does By Duane Esse When Rose Dorcey announced at the October 2015 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame (WAHF) annual meeting that she would serve for one more year, and then not seek re-election the following year, there were several concerned looks among the attendees. Then, at the October 2016 meeting it became a reality when she announced that she was stepping down from the WAHF presidency and not seeking re-election to the board. Rose has raised the bar by development of WAHF’s flagship Forward in Flight magazine, adding new programs, and increasing membership. While we’re aware of her many contributions to the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame, let’s find out about her life outside of WAHF. RACING AND FLYING Rose was born June 5, 1961 in Wisconsin Rapids, and I’m sure she became an overachiever as soon as she could talk. There hasn’t been much she has shied away from since. Growing up in the tiny Village of Biron, she was one of six children whose parents, Carl and Rose Schaetz, taught them to be responsible and selfreliant. When Rose bought her first car at age 16, a Dodge Dart with slant six, her dad taught her to do oil changes and other simple maintenance. In her pre-teen years, Rose was a member of the Biron Swim Team. “I was not a standout swimmer,” she said, “but I enjoyed relays, and never gave up on the longer, tiring events.” She was on homecoming court, and served as president of the Distributive Education Clubs of America (DECA) in high school, while working part-time in retail. Graduating from Wisconsin Rapids Lincoln High School in 1979, Rose took Marketing and Business courses at Mid-State Technical College. She graduated summa cum laude—with a double major—from Lakeland College with a Bachelor of Business Administration and Marketing. Soon after graduating from high school, Rose developed an interest in motorcycle racing—hillclimb to be exact, though she did some grass drag racing as well. Hillclimb races are won by either being the fastest to the top of the hill in Rose likes to set goals for the number of different airports she wants to fly to each year. your division, or for particularly tough hills, by climbing the farthest distance toward the top. She earned several American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) District 16 championships in the 100cc class, and became the first woman to win an AMA national amateur hillclimb championship. It didn’t necessarily come easy. At her first national championship race in 1982 in Charlemont, Massachusetts, she placed third, after an interrupted season nursing a broken shoulder suffered at a race earlier in the year. In 1983, pregnant with her first child, she sat out the season. A year later, in 1984, Rose got back on her bike, trained all summer, and then in fall won her first AMA National Amateur Hillclimb Championship in Prestonburg, Kentucky. In 1985, she did it again, placing first at the nationals in Everett, Pennsylvania. She competed again in 1986, earning the runner-up spot. She still owns a motorcycle today, a Suzuki DR200 dual purpose (on/off road) bike. With the birth of her daughter, Ja- 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame mie, in 1983, and son Luke, in 1987, it didn’t take long for her kids to start racing, mini bikes at first, and on to larger bikes. She and her first husband, Jay Parmeter, traveled with the kids to races throughout the state and country. Luke raced with great success, becoming a three-time AMA Racing Grand Champion. He was named the AMA Hillclimber of the Year for wins in three National Amateur Hillclimb classes: 250cc, Four Stroke, and 750cc classes. Luke’s racing experiences helped shape his future career path. He is currently the Video Production Manager for Feld Motorsports’ Supercross series and producer of its Chasing the Dream television series, which airs on Fox Sports 1. During this same period, Rose started Tae Kwon Do training, competing in tournaments, and progressing through the belt levels up to probationary black belt. She was weeks away from testing for the black belt when she started flight training, which resulted in her discontinuing Tae Kwon Do. She had taken an in-

WE FLY troductory flight, in part because of her interest in seeing her hometown from above. After that flight, everything changed. “I was so hooked, and no longer interested in karate classes,” Rose explained. She said she had a lifelong curiosity about flying, having grown up near cranberry marshes in Biron. As a youth, she would watch from a distance with wonder when crop-dusters sprayed the marshes. Her first airplane flight was in 1982, a trip from Mosinee’s Central Wisconsin Airport to New York LaGuardia, and then on to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and she loved everything about it. But it wasn’t until her 30th birthday, in 1991, when she took that first intro flight. She became a private pilot in June 1992, passing her check ride with Examiner Harold “Duffy” Gaier, flying out of Neillsville Municipal Airport (VIQ). Being an adventuresome person, she then asked two other new pilots with whom she had frequently studied with and trained, to go on a Canadian flight adventure. Over three days, they took turns flying segments from Wisconsin Rapids to Duluth, and then to the Canadian airports at Thunder Bay, Marathon, Wawa, and Sault St. Marie, and then to Green Bay to clear customs before returning to Wisconsin Rapids. “It was a fantastic trip for new pilots like us,” Rose said. “We had bad weather at one point and made a no-go decision, staying in Canada an extra night,” she said. “It was a great way to see beautiful Canada and continue our learning experiences.” For her instrument training 10 years later, her then fiancé, John Dorcey, used vacation days from work to conduct a 10day concentrated instrument training program with Rose. They drove 45 minutes from Wisconsin Rapids, where Rose lived at the time, to Marshfield, and rented a Cessna 172 from Duffy’s Aircraft Sales and Leasing. John quizzed Rose on the drive to and from Marshfield. They flew in the morning, broke for lunch, and flew again in the afternoon. More quizzing on the drive home. Flying 43 hours in 10 days, in hot summer weather, Rose said, “A couple times our tempers were as heated as the 85 – 90 degree days. This was just a few months before John and I were to be married, and we called the experience a good test of our relationship.” On the 11th day she flew the check ride with Pilot Examiner Gaier, and passed. She called it a “full immersion” training experience, and enjoyed it through and through. Oh, and that thing about testing their relationship, they went ahead with their wedding plans, tying the knot in the Fergus Chapel on the EAA grounds in Oshkosh on November 16, 2002. Rose and John completed an exciting flying adventure in 2010, flying to all 60 Wisconsin counties that have a public use airport. They did it in four separate flights, averaging 15 airports each, throughout the summer. Rose took pictures, started a blog and wrote about it at FlyingWisconsin.Wordpress.com. Later, she and John were asked to give presentations to EAA chapters and other groups about the adventure. “It was great when I heard from other pilots that our adventure inspired them to fly similar challenges,” Rose said. She’s currently working on commercial maneuvers and hopes for one final successful check ride with Duffy before he retires. Flying isn’t the only activity Rose enjoys. She has always loved the outdoors and biking. In 1995 she saw 1,400 bicyclists peddle through Wisconsin Rapids while participating in the 500-mile Great Annual Bicycle Adventure Along the Wisconsin River (GRABAAWR). She decided she wanted to do that, and a year later, she and her sister-in-law, Connie Schaetz, took it on. They started in Eagle River and finished six days later in Prairie du Chein. One day during the ride, Rose rode 100 miles, from Merrill to Wisconsin Rapids and then some, completing her one and only century ride. Rose’s brother, Rich, took her turkey hunting in 2014, and she shot a jake (young male) her first time out. John bought Rose a sturgeon spearing shack a few years ago and she has used it for at least three seasons on frozen Lake Winnebago, but she hasn’t speared a stur- Above: A flight with her sister-in-law, Connie, and nieces Amber and Monica, 2011. Right: A successful hunt with her brother, Rich. Photos courtesy of Rose Dorcey 13 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016

WE FLY geon, yet. Hang on—surely soon she will. Rose is a member of the WellArmed Woman, an organization with a mission to educate, equip, and empower women gun owners. She enjoys training with her Smith & Wesson .38 Special, and has a Wisconsin concealed carry permit. She also enjoys shooting sporting clays with her brother, Dave, and her niece and nephew. She began another challenge as she approached 50: running. “I can’t say I’m crazy about running,” she said, but she has participated in 5K and 10K races. FAMILY Talk with Rose for a short time and you’ll soon realize how much her family means to her. John and Rose have two grandchildren and another due in July. Their combined families offer plenty of opportunities for get togethers. Luke and his wife, Caitlin, have a son, Logan, who has captured Grandmother Rose’s heart. She drives from Oshkosh to Wisconsin Rapids once a week to spend time with him. “Being a grandmother is far more fun than I ever could have imagined,” Rose said. “I absolutely cherish every moment I spend with him.” Rose’s daughter Jamie chose an unconventional career path, but one that Mom avidly supports. She’s a Dominican Sister with the Dominican Sisters of St. Cecilia in Nashville, Tennessee, and middle school teacher in Kennesaw, Georgia. Sister has done mission work throughout the U.S. and world, traveling to several European countries and Australia, before and after entering the convent. She took a flight lesson or two before entering the convent, but flying wasn’t for her. However, she does enjoy a view from above, having recently climbed several 14ers; 14,000 foot peaks in the Rockies. VARIED CAREER Rose feels fortunate to have been a stayat-home mom with her kids while they were growing up. During her flight training, however, she worked a night shift as a radio DJ for a station in Wisconsin Rapids. When her kids were teens, she became co-owner and office manager of Golden Eagle Log Homes in Wisconsin Rapids, doing bookkeeping, payroll, and other management duties. Her experience in motorcycle racing led her to explore another love, writing. She has been a freelance writer since Rose loves spending time with her family, especially her grandson, Logan. She also enjoys occasional rides on her motorcycle. Page 15: with her son and daughter in 2013. June 1980, writing for motorcycle and aviation magazines, including: American Motorcyclist, Cycle News, Cycle USA, EAA Sport Aviation, and Aviation for Women, to name a few. She worked for three years as an assistant editor at EAA. In 2006, the Wisconsin Airport Management Association recognized Rose with its Blue Light Award, for her “excellence in reporting Wisconsin avia- 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame tion news and information.” Rose started as an Independent Consultant with the Wisconsin-based company, L’BRI PURE n’ NATURAL, in February 2015. She promoted to Senior Consultant by September 2015, and promoted again on April 1, 2016 to Supervisor. “Influenced by my older sisters, Diane and Lori, I’ve always loved messing with my hair and makeup,” Rose ex-

WE FLY Some of those accomplishments include: Tripled membership; planned and carried out the 100 for 100 membership drive in 2003. Wrote, produced, and found sponsors for WAHF’s centennial booklet in 2003, Blue Sky Moments. Began a Silent Auction in 2005 and since then more than plained. “It turns out, this is a career I absolutely love; it’s great being able to share information about healthy, aloe-based skincare ingredients with my customers, and get back to having my own business.” When she’s not serving her clients, or spending time with her family, she loves hiking trails at state parks and traveling, though she says she hasn’t done enough of that lately. She’s an active member of Most Blessed Sacrament Parish in Oshkosh, as a lector, extraordinary minister of holy communion, volunteer photographer, and cupcake baker. She has held leadership roles in the Oshkosh Women in Aviation chapter, and in 2015 was awarded the Dorothy Hilbert Chapter Volunteer of the Year award by Women in Aviation International. She’s a member of the Winnebago Flying Club, based at Wittman Regional Airport (KOSH) and serves as its newsletter editor and events co-chair. She’s also a Lead Representative for the FAA Safety Team. $27,000 has been raised to fund WAHF’s scholarships and educational outreach projects. Established and served as administrator for WAHF’s social media accounts in 2007. Wisconsin Aviation Centennial projects in 2009. Co-produced and found sponsors for WAHF’s 25th Anniversary booklet in 2010. Grew from one annual scholarship of $1,000 to four awards providing up to $4,000 annually. Took a two-page annual letter from the president and turned it into a 32-page quarterly magazine, Forward in Flight. Says Rose, “When I attended my first board meeting, I saw the organization as one with great potential for growth, and always looked for ways we could improve members’ experiences,” she explained. “The early board members did admirable work in recording our state’s early aviation history. I was fortunate to work with a dedicated team of board members, and WAHF member/supporters, who were willing to roll up their sleeves and carry out some successful programs. I’ll always support this volunteer organization for the important work it does, and I’m so thankful for the great people I’ve met through WAHF.” WHAT’S NEXT? By now you may subconsciously feel exhausted after reading about the interests, activities, and accomplishments of Rose thus far. When she develops an interest in something it becomes a full commitment, and certainly the bar is raised in everything she starts. The WAHF and its member/supporters will miss her leadership, but can feel fortunate that she will continue as editor of Forward in Flight. As she takes a much overdue rest, we’ll be listening and watching for her involvement in new initiatives and programs. Thanks for the past 15 years. WAHF With Rose retiring from the WAHF board and presidency, Board Member Chuck Swain made an eloquent presentation at the organization’s 31st annual induction banquet on October 15, 2016, summarizing Roses’ accomplishments in her 15 years’ involvement with the board. “Rose was a member of the WAHF Board of Directors for 15 years, serving as president for 12,” Swain said. “She was the sixth and longest serving WAHF president. She has led the organization as we have grown, in size and in value to our community, and we are better for her leadership. Rose would be the first to admit that everything our organization has done, every change we’ve experienced, all that was accomplished over those 15 years is due to our volunteer board and our members. Those of us who have worked alongside her, whether as board members or as volunteers, know that our organization has become what it is today due to her tireless efforts. We know that it was her inspiration, drive, and vision of what WAHF could be that has brought us to this point.” As president, Rose addressed the guests at the last twelve WAHF banquets. Photos courtesy Rose Dorcey/WAHF 15 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016

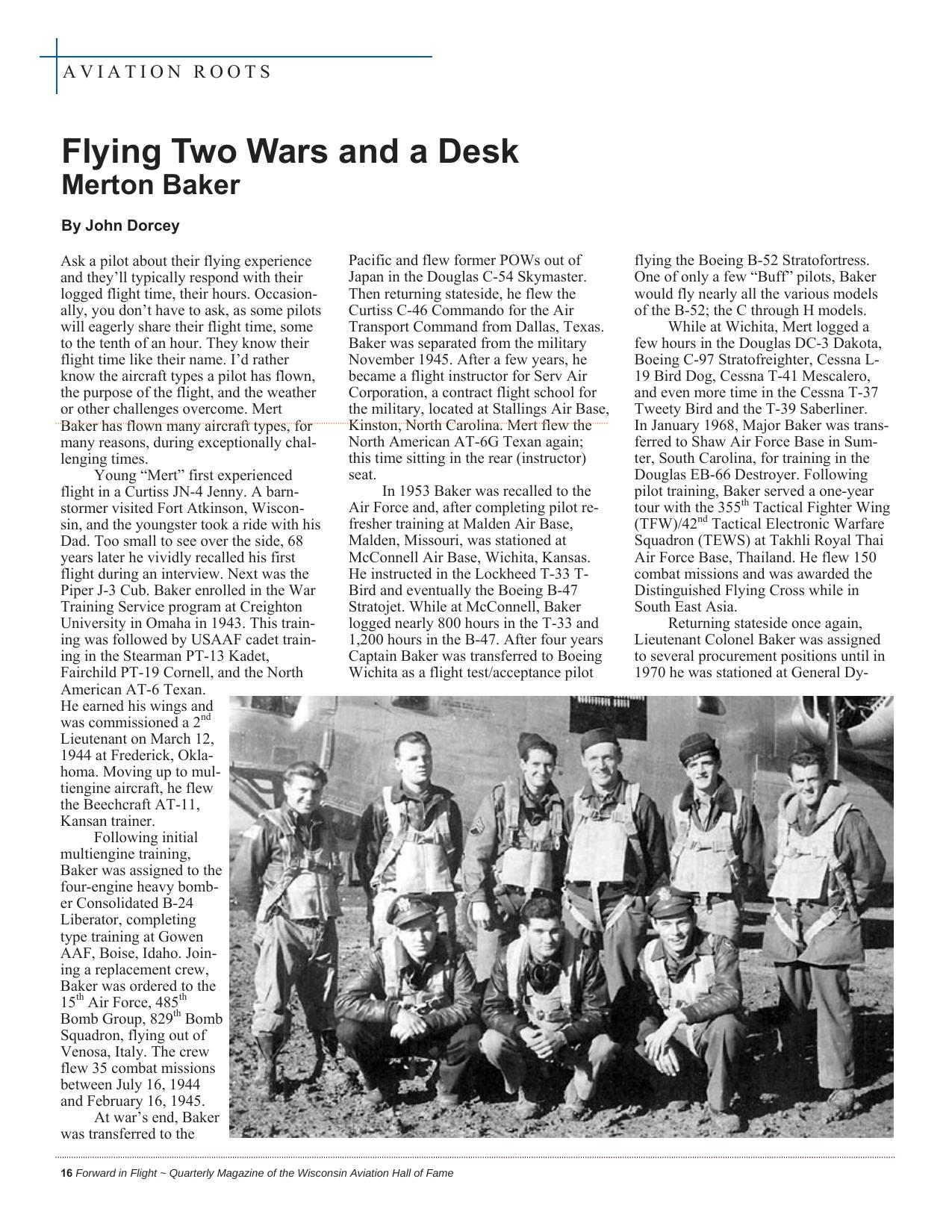

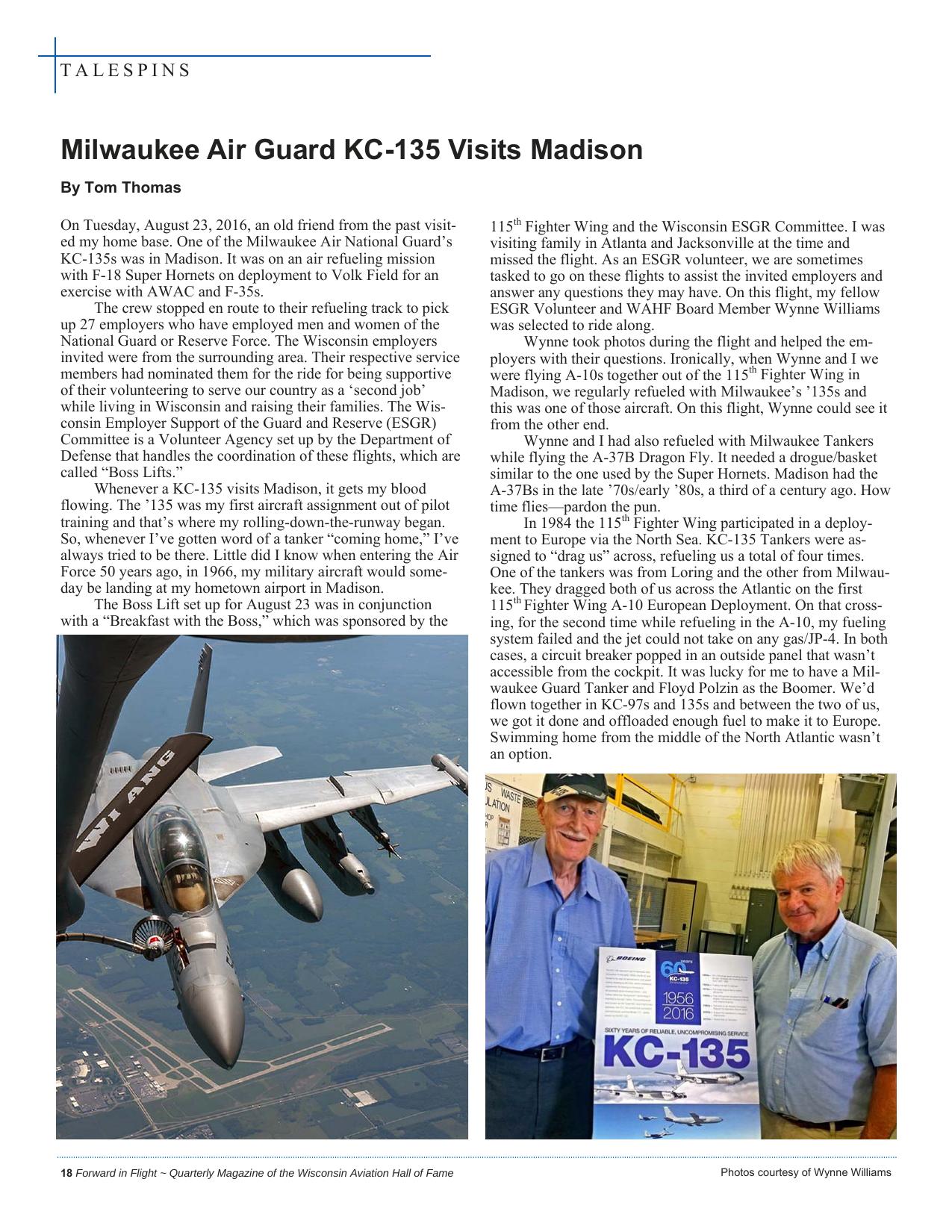

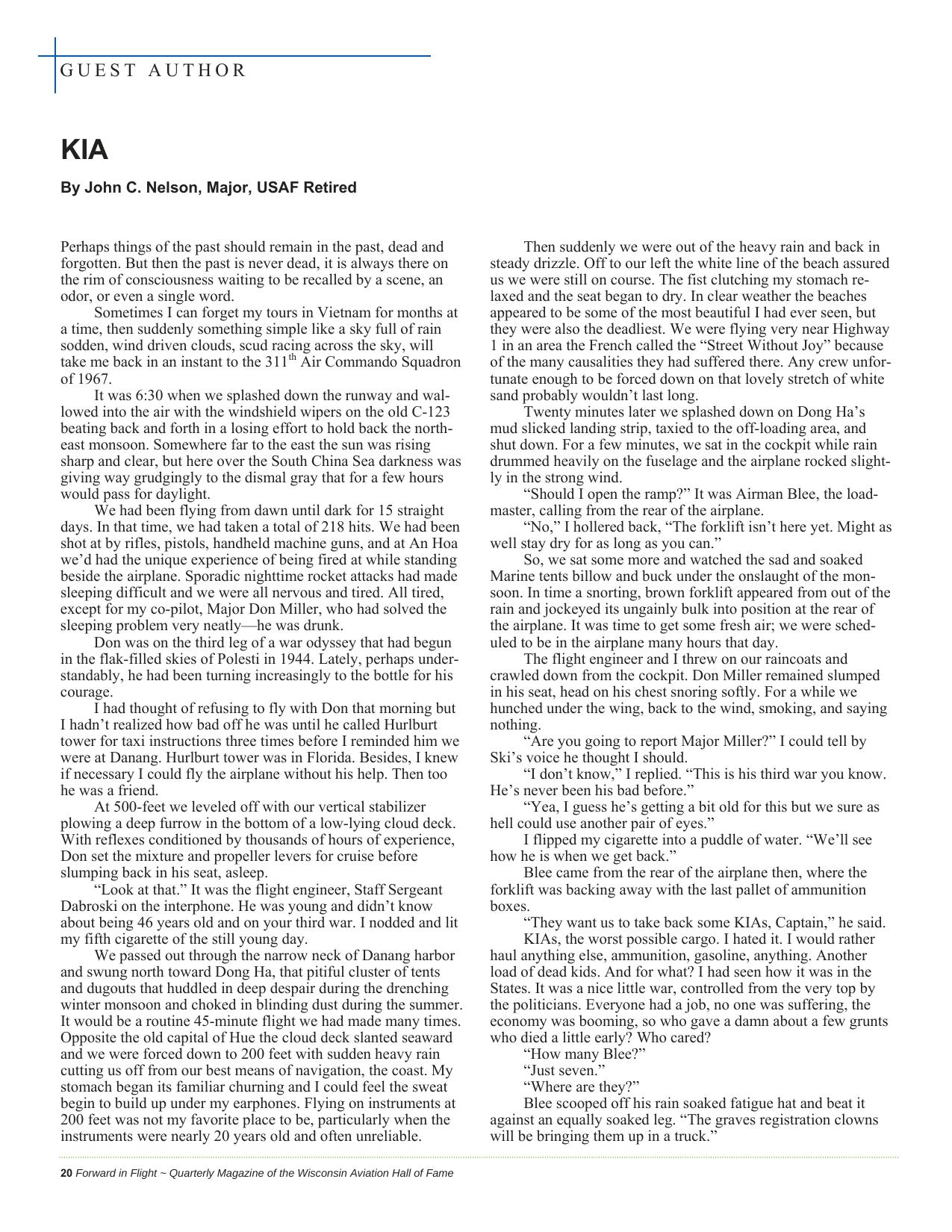

AVIATION ROOTS Flying Two Wars and a Desk Merton Baker By John Dorcey Ask a pilot about their flying experience and they’ll typically respond with their logged flight time, their hours. Occasionally, you don’t have to ask, as some pilots will eagerly share their flight time, some to the tenth of an hour. They know their flight time like their name. I’d rather know the aircraft types a pilot has flown, the purpose of the flight, and the weather or other challenges overcome. Mert Baker has flown many aircraft types, for many reasons, during exceptionally challenging times. Young “Mert” first experienced flight in a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny. A barnstormer visited Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin, and the youngster took a ride with his Dad. Too small to see over the side, 68 years later he vividly recalled his first flight during an interview. Next was the Piper J-3 Cub. Baker enrolled in the War Training Service program at Creighton University in Omaha in 1943. This training was followed by USAAF cadet training in the Stearman PT-13 Kadet, Fairchild PT-19 Cornell, and the North American AT-6 Texan. He earned his wings and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant on March 12, 1944 at Frederick, Oklahoma. Moving up to multiengine aircraft, he flew the Beechcraft AT-11, Kansan trainer. Following initial multiengine training, Baker was assigned to the four-engine heavy bomber Consolidated B-24 Liberator, completing type training at Gowen AAF, Boise, Idaho. Joining a replacement crew, Baker was ordered to the 15th Air Force, 485th Bomb Group, 829th Bomb Squadron, flying out of Venosa, Italy. The crew flew 35 combat missions between July 16, 1944 and February 16, 1945. At war’s end, Baker was transferred to the Pacific and flew former POWs out of Japan in the Douglas C-54 Skymaster. Then returning stateside, he flew the Curtiss C-46 Commando for the Air Transport Command from Dallas, Texas. Baker was separated from the military November 1945. After a few years, he became a flight instructor for Serv Air Corporation, a contract flight school for the military, located at Stallings Air Base, Kinston, North Carolina. Mert flew the North American AT-6G Texan again; this time sitting in the rear (instructor) seat. In 1953 Baker was recalled to the Air Force and, after completing pilot refresher training at Malden Air Base, Malden, Missouri, was stationed at McConnell Air Base, Wichita, Kansas. He instructed in the Lockheed T-33 TBird and eventually the Boeing B-47 Stratojet. While at McConnell, Baker logged nearly 800 hours in the T-33 and 1,200 hours in the B-47. After four years Captain Baker was transferred to Boeing Wichita as a flight test/acceptance pilot 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame flying the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress. One of only a few “Buff” pilots, Baker would fly nearly all the various models of the B-52; the C through H models. While at Wichita, Mert logged a few hours in the Douglas DC-3 Dakota, Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter, Cessna L19 Bird Dog, Cessna T-41 Mescalero, and even more time in the Cessna T-37 Tweety Bird and the T-39 Saberliner. In January 1968, Major Baker was transferred to Shaw Air Force Base in Sumter, South Carolina, for training in the Douglas EB-66 Destroyer. Following pilot training, Baker served a one-year tour with the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW)/42nd Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron (TEWS) at Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. He flew 150 combat missions and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross while in South East Asia. Returning stateside once again, Lieutenant Colonel Baker was assigned to several procurement positions until in 1970 he was stationed at General Dy-

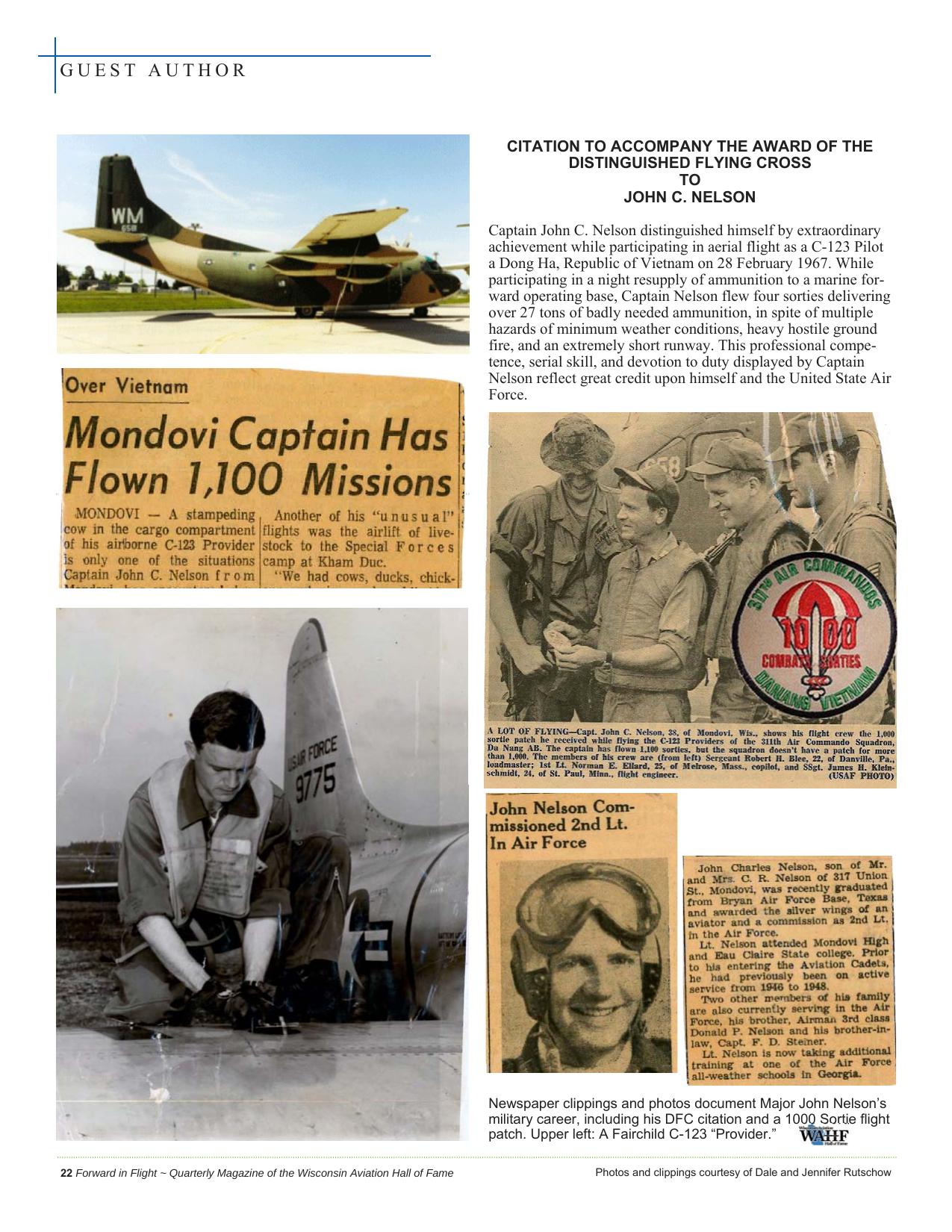

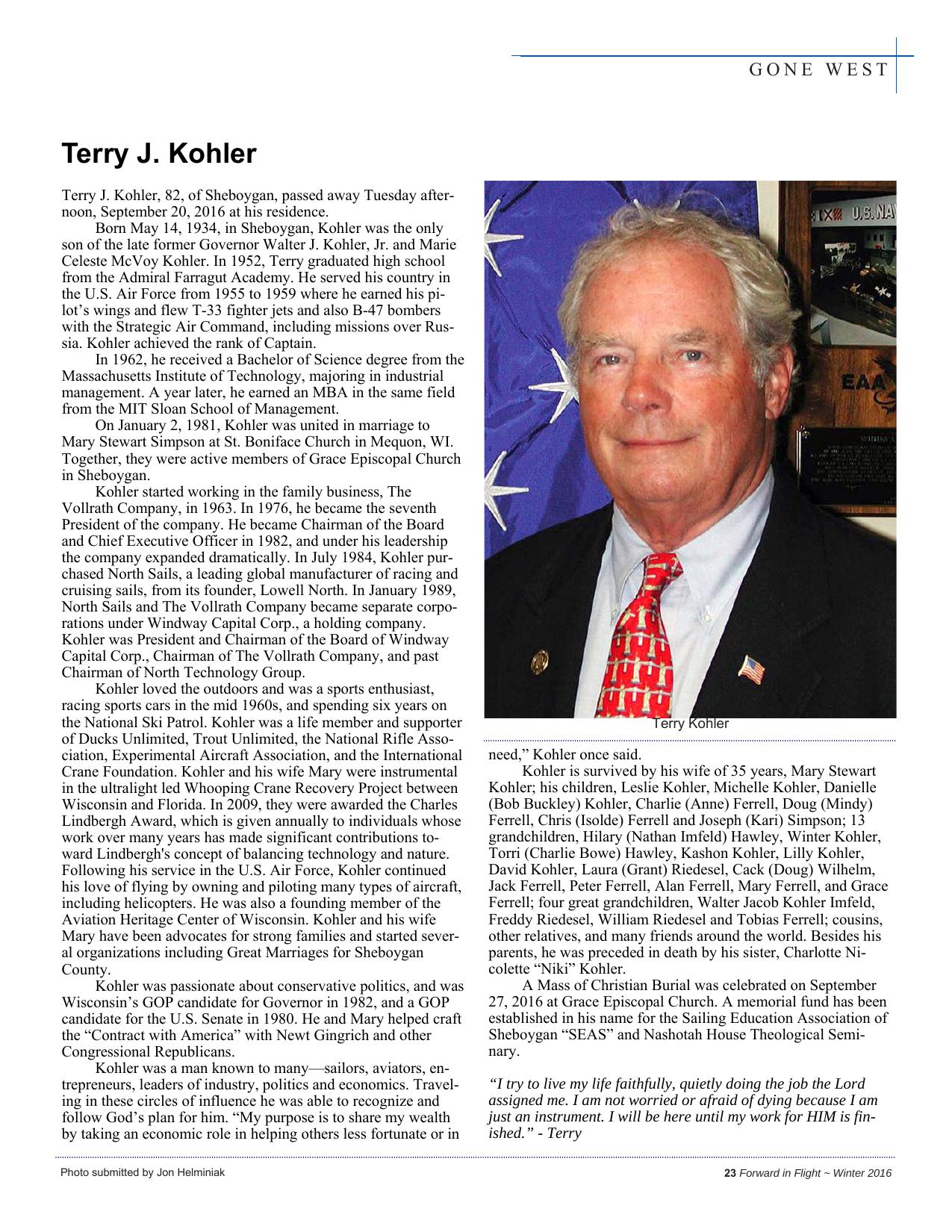

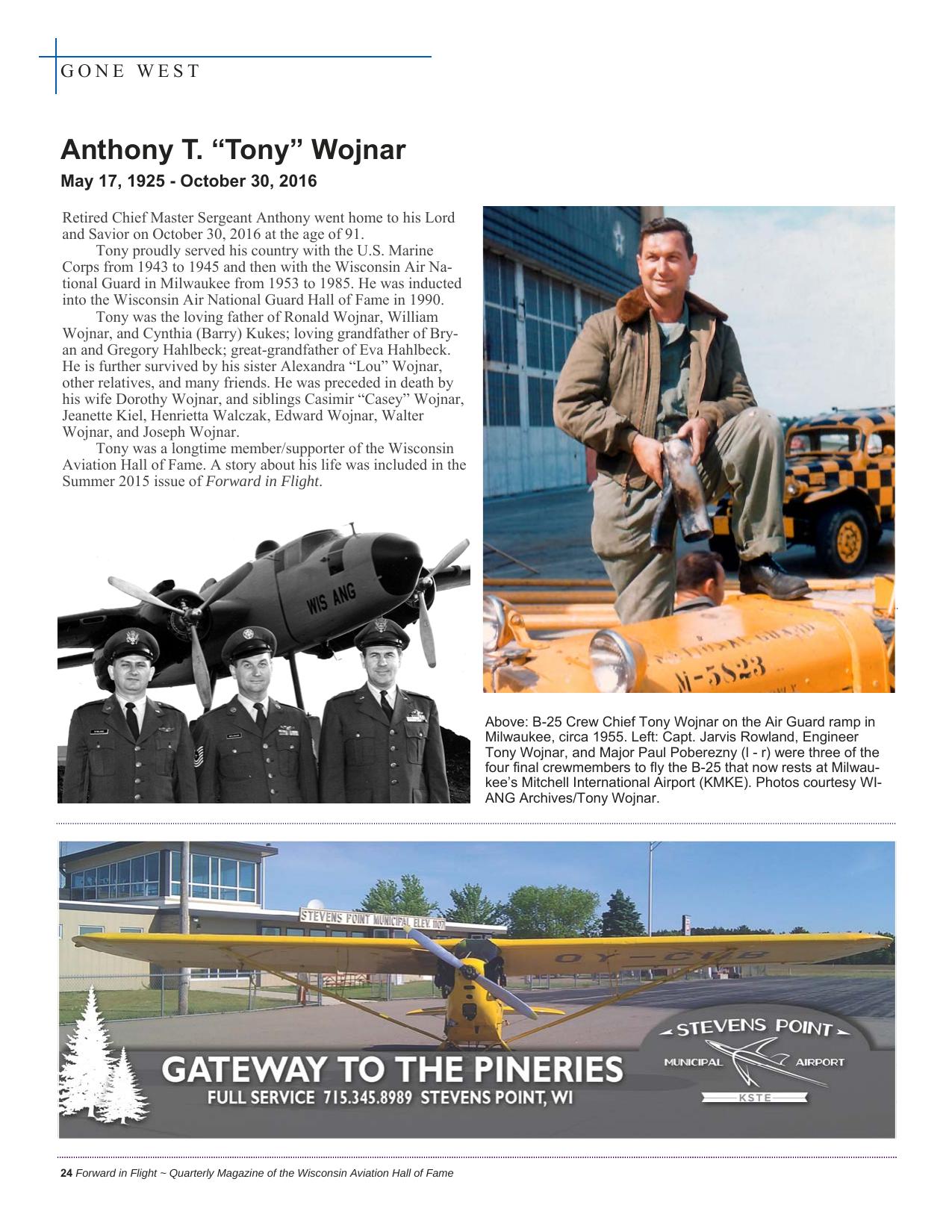

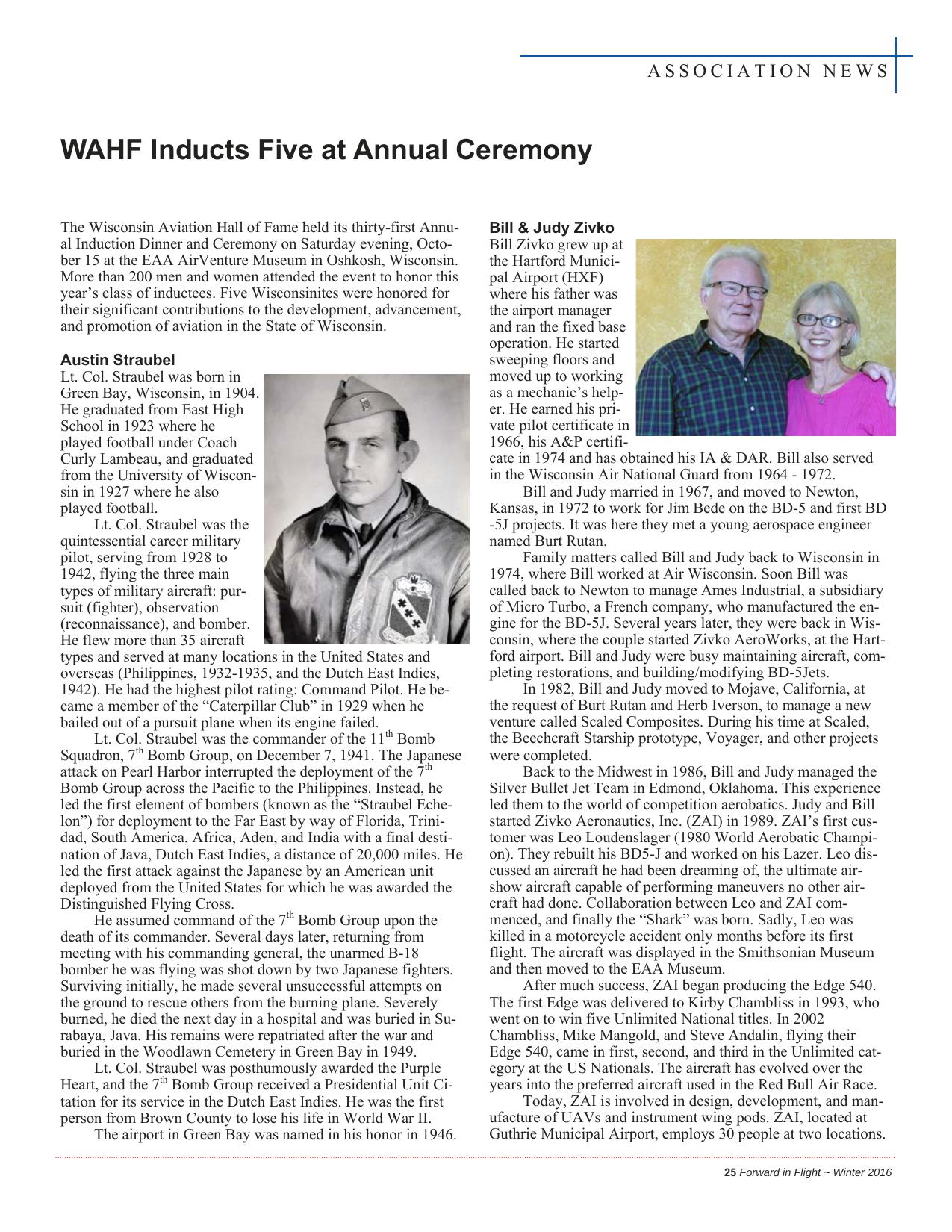

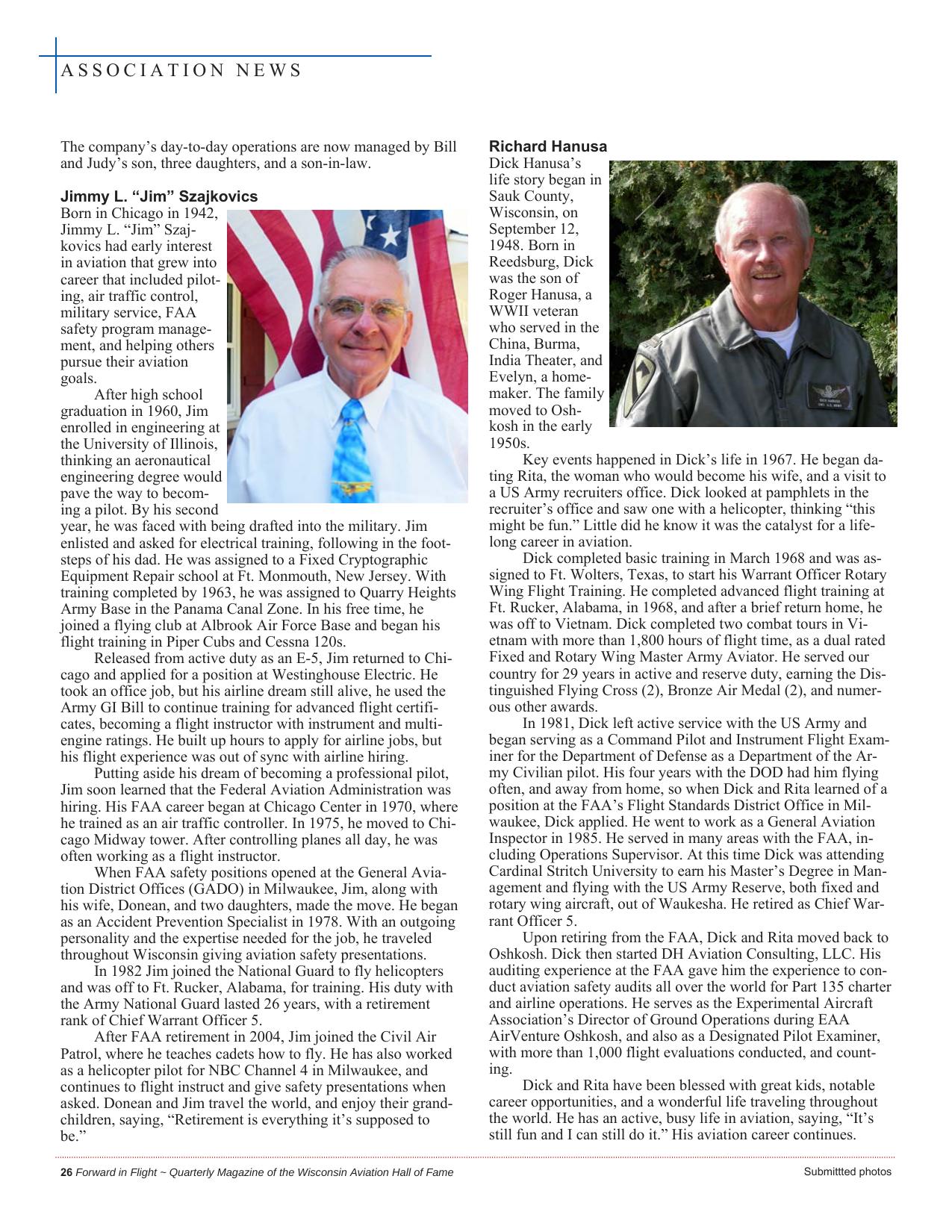

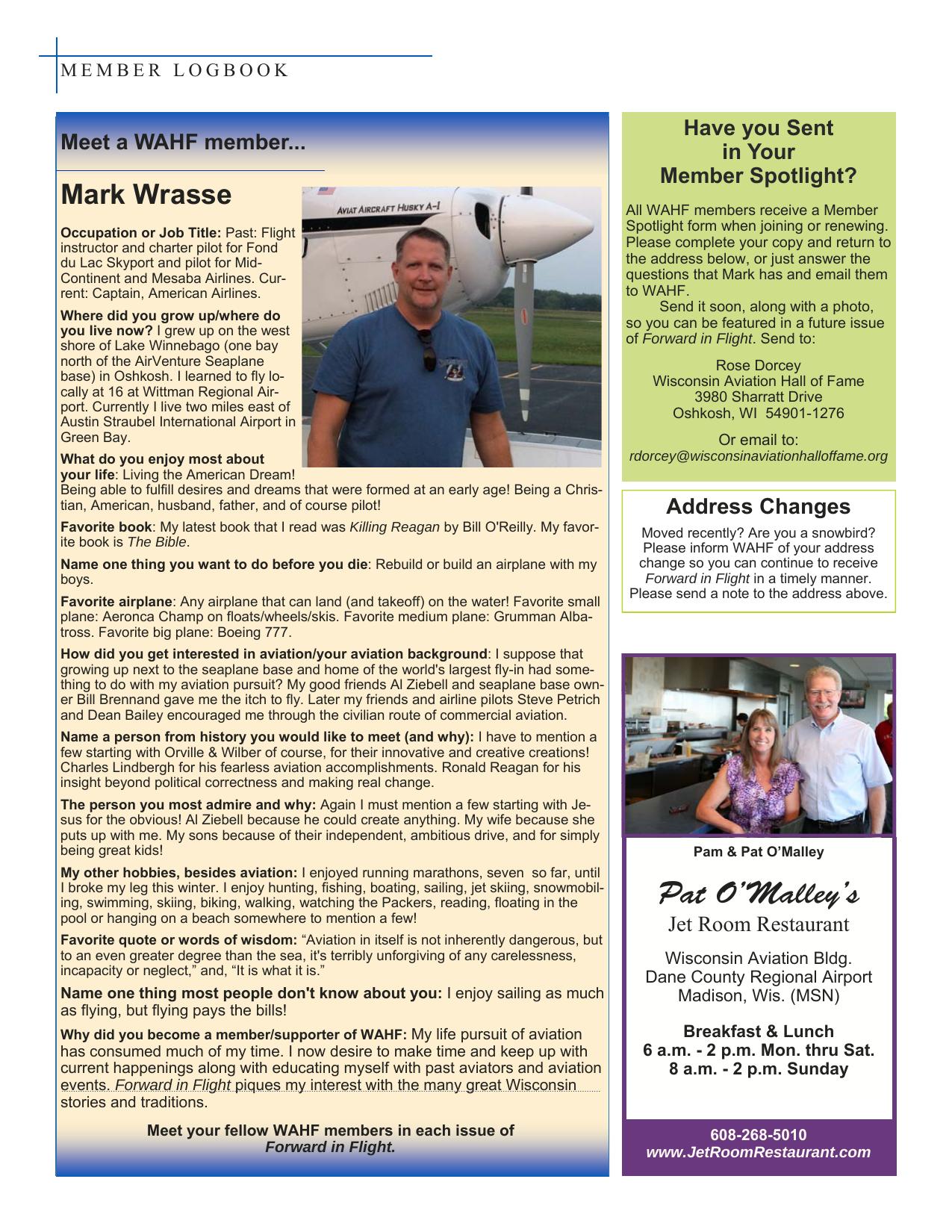

AVIATION ROOTS namics, Fort Worth, Texas as Air Force Plant Representative. While on this assignment, he flew the supersonic General Dynamics FB-111 Aardvark. During a December 30, 1997, oral history interview, when asked about his flight time Major General Baker responded, “Hmm, a little over 7,000 hours.” When asked about the aircraft he flew he provided specifics, many with detailed stories; stories of 185 combat missions, training flights, and award-winning flights. Baker flew at least 20 different types and different models of those types. MGen Baker was born in Tomahawk in 1924, grew up in Fort Atkinson, and graduated from Evansville High School in 1942. He attended Whitewater State Teachers College for one semester before transferring to Creighton University in Omaha. His military decorations and awards include the Legion of Merit with oak leaf, Distinguished Flying Cross, Meritorious Service Medal, and the Air Medal with 11 oak leaf clusters, among others. Merton Baker died in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on July 19, 2000. He is a nominee for induction into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. Previous page: Consolidated B-24 “Liberator” Homeward Angel crew Venosa, Italy ca Aug 1944. Baker is front row on right. Clockwise: Main gate, Malden Air Base, Malden, Missouri, ca 1950s. Douglas EB-66 “Destroyer” 42nd TEWS, Takhli Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand. Merton W. Baker, Major General, USAF June 1980. Photos courtesy of USAAF/USAF and Malden Army Airfield Preservation Steering Committee 17 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2016