Forward in Flight - Winter 2017

Volume 15, Issue 4 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Induction Banquet No. 31 Honoring Wisconsin’s finest A Farm Boy in Europe Williams’ WWI career Winter 2017/2018

Contents Vol. 15 Issue 4/Winter 2017 A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame FLIGHT LOGS 2 Home After Dark Night Flying 101: The planned and unplanned Elaine Kauh, CFI WE FLY 13 World War I A brief history - and family connections John Dorcey MEDICAL MATTERS 4 I, Eye, Aye More than the eye can see Dr. Reid Sousek, AME ASSOCIATION NEWS 14 2017 WAHF Induction Banquet Honoring the finest of Wisconsin aviation RIGHT SEAT DIARIES 6 Professionalism in Flight For anyone in aviation Dr. Heather Monthie FROM THE ARCHIVES 8 Rodney Williams Wisconsin’s first ace Michael Goc TALESPINS 12 The Russians Are Coming How one Russian airplane landed at Marquette Tom Thomas We’re delighted to present this special banquet issue of Forward in Flight. Held October 21, 2017, the annual induction event serves to perpetuate the memory of the persons who have made aviation achievements, and encourage a better sense of appreciation of the origins and growth of aviation in Wisconsin. A large crowd was on hand to honor and welcome this year’s inductees. FROM THE AIRWAYS 22 Cupcakes for Scholarships, and more... EDITOR’S LOG 23 Sharing the Joy of Flight Oh the wonder in a three-year-old’s eyes Rose Dorcey MEMBER SPOTLIGHT 24 Ken Cook, Jr.

President’s Message By Tom Thomas WAHF’s recent annual induction ceremony was a great tribute to the four individuals selected for induction this year for their distinguished aviation careers in Wisconsin and beyond. This event also included our two scholarship winners who have began their educations with the goal of becoming active players in the future aviation industry in coming years. The gathering was akin to a reunion of Wisconsin’s aviation family. They came from far and near to honor this year’s inductees and talk with colleagues from years gone by. Hand-inhand in the national airspace system they worked on methods to improve the system they flew in daily formations crisscrossing the country, oceans – the world. Those who have ‘shaken the stick’ become not only enthralled with their job, but it soon becomes their avocation. Many attendees have become regulars for the opportunity to network with fellow pilots as we continue to carry the banner of fostering and promoting aviation in our own way, in our own worlds. As a flying profession and or hobby, many are compelled by our love of flight to share the love, the joy of flight, and share the passion. Knowing that aircraft are time machines, whether it’s a hot air balloon, crop duster, flight for life helicopter, an F-16 fighter jet, or Boeing 777, the bond is universal. Our induction setting in the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) world headquarters, with aviation of all sorts and sizes, colors and shapes, is fitting, dignifying the WAHF ceremony and inductees. Many of our inductees have had ties with EAA as many of our objectives overlap. We in Wisconsin are truly blessed to have the EAA within our boundary. The seed to develop this worldwide movement and organization began from the heart and soul of Wisconsin itself. Now annually hundreds of thousands of aviation enthusiasts come to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to attend the world’s largest most diverse aviation event. This year alone 15 past inductees attended this year’s ceremony to not only honor but also welcome the new inductees and see old friends. It is in their blood, the bond of the flight. Flying in the sun, through the clouds, sometimes riding the turbulent air deep within cloud systems while occasionally encountering icing conditions forecast (and not forecast) while communicating with air traffic control, other aircraft by radios, light signals and sometimes by hand signals. Stories are shared, and new innovations and requirements proposed are discussed at length. This year’s Ceremony at the EAA Museum was all that and more. Many of those who attended are putting next years event on their calendar for October 2018. Come join in the 2018 Induction Ceremony to help honor those who helped develop Wisconsin’s aviation history and traditions. (l-r) Jerry Mehlhaff, 2005 WAHF Inductee, and John Chmiel, of Wausau Flying Service, found the WAHF induction ceremony a great place to catch up and discuss opportunities and challenges in aviation today. Forward in Flight The only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s events. Rose Dorcey, editor 3980 Sharratt Drive Oshkosh, WI 54901-1276 Phone: 920-279-6029 rdorcey@wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. On the cover: Tracy Nettleship, daughter of Gene Chase, represented her father as he was inducted into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame on October 21, 2017. The thirty-first annual event ushered in a new class of four inductees. Read more beginning on page 14. Photo by Chris Palmer.

FLIGHT LOGS Home After Dark Night Flying 101: The planned and unplanned By Elaine Kauh For the first time in several months, I landed an airplane at night. It’s an unofficial semi-annual ritual that tends to just happen—meaning it’s almost never planned. One minute I’m basking in a bright sun warming me through the window of the Cessna, the next I’m watching the same sun dipping below the horizon and feeling colder. Then I get my wits about me and remind the pilot in the right seat that we ought to “think about turning for home, as it will be just past sundown when we land.” Sure enough, the sun disappears entirely 20 minutes later, leaving a pretty orange but cold halo peeking above the horizon. We’d already flipped on the nighttime and landing lights on the Cessna and by the time we touch down (on a well-lit runway) there’s not much natural light left to see by. Then it’s time to taxi back to parking amid a sea of blue taxiway lights that don’t offer much by way of guiding you in the right direction—just barely enough to keep you on the proper piece of pavement while you slowly grope your way in. Landing lights on small airplanes, as in this case, aren’t going to do more than dimly illuminate the six feet you’re about to roll across, so the slower the better. This is one of the reasons why I don’t prefer to move around in an aircraft in the dark, much less take off and land. It can be daunting enough to spot wildlife scurrying in front of you in the daytime; at night, the threat is more hidden and the margin to react, tiny. But night flights do happen, planned or otherwise, and so a couple times a year this ritual of remembering how to fly at night comes up by surprise and it’s always a matter of reminding ourselves: Oh yes, it’s time to get night current again! It’s always around early March, when the gradually warming weather with lengthening days triggers the need for the springtime version of the ritual and getting night refresher training. I find myself pushing the day’s last flight past 6 o’clock, watching the sun going down. I know that when it’s well over 40 degrees, the threats of icy runways and frosty wings are gone, at least until the next stretch of chilly evenings, which around Wisconsin linger on through June. Daylight savings hasn’t kicked in yet, and so it’s still quite early when we finally turn for home. Then the days start to get later and later until we’re out well past 8 o’clock, still wearing sunglasses, and either sweating our way around the pattern or descending from 6,000 feet because we felt like practicing our glides in the natural air conditioning. Then October rolls around. Even before the dreaded time change from Daylight Savings kicks in, I get caught around that same 6 o’clock window with the sun setting and me (usually with another pilot) realizing that it’s time for a night landing, whether we feel like it or not. That thought always gives me pause, because having plenty of experience landing at night isn’t quite the same as having plenty of recent experience landing at night. Happens every fall. This year, there was just enough dusk left to feel like I still had most of the visual cues landing as during the day: I could see the runway numbers and white stripes along with the runway lights; I could see the pavement flowing beneath the aircraft nose as I gently raised it to make the landing. Would I have been just as comfortable had it been closer to 7 o’clock, an hour after sunset, and totally dark? I’d say not quite as comfortable, as after months of daytime summer flying it does take a night or two to get used to the different environment, where the visual cues we depend on aren’t there and a few extra safety precautions kick in. So that landing the other day was a good way to make the transition. Still, it’s time to get 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame more practice... Flying at night isn’t a common occurrence for those who fly for fun and to see the sights. It’s a necessity for everyone else, who travel on schedules and such, and it’s an occasional requirement for those like me who conduct flight training. From a pure flying standpoint, nights can be a magical time to see the landscape from the air. Watching sunsets on a clear horizon is a favorite sight. City lights are also pretty at night, as are moonlit skies over snow-covered countryside. On those nights, you can see almost as well as at dusk. I’ve seen a full, pearl-like moon reflected on dark lakes around Wisconsin, a visual effect you can only see from flying not too far above the ground in a small airplane. I have even seen the airplane’s shadow zooming across undisturbed fields of snow with a full moon shining above me. On most nights, the flying air is as smooth as it is at dawn. Starting at dusk, the air gets still as winds and solar warming taper off. It is so smooth that you can feel like you’re sitting perfectly still on the ground as you watch the ground go by. Anyone riding with you, even those reluctant passengers, will tell you that flying in such still air really is the way it should be. If only air travel could always be so smooth, at all times of day and in all weather, it would make it seem much more like the “time travel” we’d like it to be, with the idea that you can just sit in a plane for a period, then disembark in a completely different time zone and climate. With all that scenery and silkysmooth air at night, why is it so rare to go

FLIGHT LOGS On most nights, the flying air is as smooth as it is at dawn. Starting at dusk, the air gets still as winds and solar warming taper off. It is so smooth that you can feel like you’re sitting perfectly still on the ground as you watch the ground go by. flying after dark? Summer nights are a great time to enjoy the sights at night without the cold weather, but you must wait until quite late to make it work. Early spring and fall nights aren’t as appealing due to the nighttime chill that sets in. Unless you’re training, or you are traveling on a schedule, the urge to go out in the cold to fly in the dark really does taper off with the shorter days. It can be tough even if you do want to go. Once it hits the right temperatures, frost can settle on aircraft wings while you’re just getting it ready to fly. That’s an automatic no-go. Just a bit of a frosty layer on a wing is enough to disrupt its ability to lift you off the ground. Cleaning it off and keeping it clean until you start the propeller is a tough ordeal, as the frost just reforms once you’ve wiped it off with a warm towel. Then there’s a list of rules and precautions for flying after dark, which is why those learning to fly must get trained in what to expect. At sundown (or prior to sunrise), your airplane must have the small red, green, and white navigation lights on so others in the air can mark your wingtips and tail at night and tell whether you’re moving left, right, towards, or away. So the simplest of aircraft, those without an electrical system or are equipped just for daytime, must be back on the ground before sunset and can’t go back out until sunrise. A landing light, while not strictly required for personal use, is also a great way to be seen and makes taxiing, takeoffs, and landings far safer at night. I’ve Photos by Elaine Kauh Getting properly adjusted to night flying can require some good refresher training. Previous page: Flying at night offers great views of sunsets and airport lighting. had several instances of landing lights not working while trying to land in the dark, even though they were just checked prior to departure. For this reason, I make it a point to have every pilot undergoing night-landing training to practice touchdowns without the landing light, just in case it ever happens to them. Feeling your way to a dark runway for that last few feet, your nose tentatively raised up, not too much and not too little, would be a bit scary if you’ve never done it. And having to do it, with no choice in the matter, isn’t my first choice, but it’s not too bad with a little practice and using more of your peripheral vision. Whether daytime or nighttime, you must have an aircraft with good working everything, not just lights, but at night it’s even more crucial. Best to check your flaps and flight controls during the day outside or in a well-lit hangar. Short of broad daylight, it takes a good, strong light to peek into the fuel tanks and see how much gas is in there, and to inspect the clarity and proper coloring of the fuel when you sample the tanks. Pre-flighting on a cold, dark, poorly lit ramp, even with a big flashlight, is nowhere nearly as good as preflighting in the comfort of a well-lit building, where you will be more thorough. Pilots must also be ready to go at night. To carry passengers more than an hour after sunset requires that they be night current, meaning three takeoffs and landings were done at night in the last 90 days. This ensures that you’ve done at least a small amount of recent practice before taking passengers. From discussing night preparation with others, I’ve also learned that it helps to take an inventory of equipment to make sure you have what you need ready to go and in reach: A good working red-lens flashlight to see maps and other items in the cockpit at night, and a good working white flashlight for emergencies. Now that’s a good semi-annual ritual to put on the calendar for March 1 and November 1—checking the night-flight kit for bulbs and batteries, and while at it, double-checking aircraft lights. This would go a long way to getting home safely after dark when the sun sets sooner than you’d like. Elaine Kauh is a flight instructor and aviation writer who enjoys flying around Wisconsin and elsewhere. E-mail her at elainekauh@icloud.com. 3 Forward in Flight – Winter 2017/2018

MEDICAL MATTERS I, Eye, Aye More than the eye can see By Dr. Reid Sousek Sometimes we find that a single letter can make a major difference. In aviation, we would generally want more altitude than attitude. In medicine, you would rather take a medication that is PO than PR (opposite of oral route...a truly eye-opening experience). When out in the woods, you would rather have a beer in camp than a bear in camp. Sometimes I am not sure if I’d rather go out for a run or a rum. When your AME is assessing your vision, there is more being assessed than just telling the difference from a “C” and an “O” on the wall chart. The AME Guide (https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/ headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aam/ame/guide/) very specifically documents vision standards and exam techniques. Exam components are numbered 21-58 and correlate with specific blanks on the 8500-8 form (Items 1-20 are completed by the pilot when completing MedXpress on the computer.) Nine of the 37 exam components are related to eyes and vision. These include Eyes, Ophthalmoscopic, Pupils, Ocular Motility, Distance Vision, Intermediate and Near Vision, Color Vision, Field of Vision, and Heterophoria. For the Eyes component, the examiner is assessing for general eye conditions. Red eyes may be a sign of allergies, or worse, a sign of glaucoma. Exophthalmos (abnormal protrusion of eyes) may be a sign of hypothyroidism. Kayser-Fleischer Rings may suggest underlying metabolic disease (abnormal copper metabolism). Consider this portion of the exam like what you look at as you walk up to your plane (any abnormal puddles or leaking fluids, flat tires, etc.). Next, we move to Ophthalmoscopic and Pupils. Initially, we are more closely inspecting the cornea, iris, and pupil. Using the ophthalmoscope, an examiner can look through the pupil and complete the fundoscopic exam to see the retina and optic nerve. The fundus is the back or interior part of the eye. The eye fundus is the only part of the body where blood vessels can be directly visualized, therefore it can give clues to underlying medical conditions. Thickened vessels or asymmetric/nicked vessels may be an indication of high blood pressure. Optic nerve changes may be suggestive of intracranial changes. The fundus or retina exam performed at an aviation exam is limited compared to the view seen by an eye specialist when dilating drops are used, so you still need regular comprehensive eye exams by an optometrist or ophthalmologist. Item No. 34 is Ocular Motility. In medical shorthand, a normal ocular motility exam may be abbreviated PERRLAEOMI. This stands for Pupils Equal Round Reactive to Light and Accommodation - ExtraOcular Movements Intact. The first portion of this test is to evaluate general alignment of the eyes. (See separate discussion of phorias and tropias below.) A quick shine of a light in the eye can assess the response of the pupil, but the opposite eye’s response is also evaluated. Accommodation is assessed as the eyes focus on a very near object and the pupil changes size. The motion of the eyes is controlled by six muscles that move in a coordinated fashion to align the eye during different directional gaze. Four of these muscles are aligned essentially on the “N, S, E, W” quadrants of the eye. Two of 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame these muscles are oblique muscles, which will play a role in torsion or diagonal motions. (Interestingly, there are three different nerves involved in signaling to these six muscles, so failures in certain motions can help pinpoint the location of a brain lesion). I test this by having the patient follow my finger or a light in an “H” like pattern to test all of these planes of motion. Nystagmus, a repetitive beating like motion of one or both eyes, may be an indication of an underlying medical issue (or being under the influence of a substance, which is tested at a DUI test). Possibly the most familiar eye test is reading the wall chart. This is the “Distance Vision” component. You will be asked to read some letters on a wall chart at 20 feet (some clinics use a vision testing machine or a differently sized chart to allow for less than 20-foot viewing distance). A commonly used distance vision chart is the Snellen Chart. This consists of nine or 10 different letters: C, D, E, F, L, O, P, T, and Z. These letters are specifically chosen for the chart as they will help identify errors with horizontal, vertical, or diagonal image components. Visual acuity is often stated as a fraction of “X” over 20. The “X” will be the individual’s result compared to the normal vision at 20 feet. Vison of 20/15 would mean the tested individual can see at 20 feet what the normal individual can see at 15. A vision of 20/100 or worse may meet the criteria for legal blindness. The tested individual must be no more than 20 feet from an object to see what a normal individual can see at 100 feet. The actual vision standards differ based on what class of medical you are seeking. For 1st/2nd class medicals (airline transport/commercial) the distance standard is 20/20. For 3rd class, the minimum is 20/40. This must be achieved in each eye individually and both eyes together. If correction (contacts or glasses) is used to meet these standards, it would then also be needed for flying and a limitation such as “must wear corrective lenses” would appear on the certificate. Three common visual errors that would require corrective lenses (refraction) include hyperopia, myopia, astigmatism. Hyperopia (farsightedness) means that an individual can see distant objects but has difficulty with near objects. In farsighted individuals, the light is not focused on the retina, but rather would focus behind the retina. The refractive power of the eye is not strong enough. This may be due to too little curvature of the cornea/lens or the eyeball being too short. The opposite is true in myopia (nearsightedness). In these individuals, the refracting power of the eye is too strong. The light is focused in front of the retina. A third type of visual refractive error is astigmatism. In these individuals the optics of the eye are not spherical and may not allow light to be focused on a single point. According to the 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES), the percentage of adults over age twenty with a significant refractive error (hyperopia, myopia, astigmatism) is over 51 percent. This number jumps to over 55 percent if looking at just those over age 40. Another aspect of vision tested is near vision. In 1st, 2nd, and 3rd class exams the near vision must meet 20/40. Near vi-

MEDICAL MATTERS Vision screeners, like this one by Keystone, are common at your AME’s office. They test for all of the essential visionary functions including acuity (monocular and binocular), color blindness, peripheral vision, and glare recovery. Right: A Snellen chart is an eye chart that can be used to measure visual acuity. Snellen charts are named after the Dutch ophthalmologist Herman Snellen who developed the chart in 1862. sion is tested at 16 inches using either a specialized vision testing machine or a Near Vision Acuity chart. If glasses are needed to meet this standard but are not needed for distance (i.e. reading glasses), the certificate would then state, “must have corrective lenses available for near vision.” Intermediate vision testing is required only for 1st and 2nd class exams of pilots over age 50. This tests visual acuity at 32 inches...roughly the instrument panel distance from a pilot. Item No. 52 on form 8500-8 is color vision. Up to 8 percent of males have some form of color vision impairment. However, a pilot may have a color vision deficit and still be able to pass the required testing. Color vision may be tested with a specialized vision tester or with color plates (Ishihara plates). The Ishihara plates have multiple differently sized and colored circles with a number on the background created by using different colored sets of circles. For example, if the contrasting color is green on a red background and an individual is red-green deficient they may not see the number pattern whereas an individual with the ability to differentiate the red-green can clearly see the pattern. Even if an airman fails color testing he may be able to fly with the limitation “not valid for night flight or under color signal control.” The tests performed in the office are screening tests and even if failed, a pilot may still have appropriate color vision to safely fly. In these cases, the pilot may be required to pass an Operational Color Vision Test (OCVT) to receive a 3rd class medical. The OCVT consists of a Signal Light Test which requires identification of aviation red/green/white lights. Additionally, the airman must be able to adequately read an aeronautical chart. If needing to upgrade to a 1st or 2nd class certificate, the pilot would then also undergo a Color Vision Medical Flight Test (CVMFT). This is performed in the aircraft and in-flight. These tests are not done by the AME, rather they are done through a Flight Standards District Office (FSDO). If passed, the pilot would then be issued a Letter of Evidence (LOE), which should be provided for the AME at subsequent exams Field of vision testing is also completed. This is testing for loss or decrease of peripheral vision. Loss of a visual field may suggest a condition of the eyeball itself or a problem with the visual pathways in the brain. A vision test not required for 3rd class exams, but included in 1st and 2nd class, is phoria testing. Phoria testing is done with a Maddox Red Rod or specialized vision testing machine. A Photo by Keystone The aviation medical certification requires in depth vision testing. Abnormalities to vision or to the eyes can be related to other chronic medical conditions or simply a matter of optics. phoria is a misalignment of the eyes that happens intermittently or functionally. This is contrasted with a tropia, which is a fixed deviation of eye alignment. Phorias may occur in the vertical or horizontal plane of vision. This may be more prominent during times of fatigue and eye strain and could affect a pilot’s ability to accurately judge depth perception or may lead to double vision (diplopia). If any chronic eye conditions or deficits exist, the FAA may require form 8500-7 (Report of Eye Evaluation) to be completed by an eye specialist. It may speed up your certification process if you have your eye specialist complete this prior to visiting your AME. Medications, such as Plaquenil/ hydroxychloroquine used for certain types of arthritis, can affect the eye, and would require a form 8500-7 with each medical application. Chronic eye conditions such as Glaucoma will also require specialist evaluation and may not be disqualifying if stable and controlled. Another vision related consideration for pilots even after the exam is sunglass choice. Polarized sunglasses may be an issue if the windscreen is polarized or the glass on a PFD or instrument is polarized. Additionally, “blue-blocker” glasses may block specific wavelengths of light coming from some glass cockpit instrument screens and are not recommended. The aviation medical certification requires in depth vision testing. Abnormalities to vision or to the eyes can be related to other chronic medical conditions or simply a matter of optics. There really is “more than the eye can see” when it comes to an aviation medical eye exam. 5 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018

RIGHT SEAT DIARIES Professionalism in Flight For anyone in aviation By Dr. Heather Monthie I will never forget the time I was working line service at the airport when I was 20 years old and had my first experience with a pilot who was rude and condescending towards me. I was there to greet him and his crew and to find out if they needed fuel. Inside the FBO, he saw a small garbage can next to the front that was too full for his liking. This was absolutely nothing to do with anything we were discussing, and it was like a switch flipped. He used this tiny garbage can with the receptionists take out bag in it as an opportunity to belittle and degrade me and to try really hard to embarrass me in front of my co-workers and the first officer. The look the first officer had on her face as he was trying to tear me down was one of “I am so sorry. He does this all the time and I don’t know what to do.” It was at that point in my life that I realized that not everyone understands the idea of treating others with respect and maintaining a professional attitude. When I saw him use a small thing as the excuse to try to manipulate, belittle, and degrade others for no reason, it became a pet peeve about professionalism for me. Before writing this article about professionalism, I posted a question in a few aviation Facebook groups that I am a part of. I wanted to know what some of the other pet peeves people having regarding professionalism (or non-professionalism) in aviation. There were a lot of great responses that fell into the eight categories listed below. While this is in the context of aviation, flight training, and the airport environment, they can and should apply across all areas of life! Professional communication Most of the comments I received about professional communication were related to radio communications. Keep it professional on the radios and know what you’re going to say. This one is tough for me because I know how intimidating radio communications can be for student pilots or pilots who don’t have a lot of experience on the radios. Most of the suggestions were to just sound professional, don’t say things you don’t need to say, like “with you”, or starting all your calls with “and...”. Also make sure your mic is a proper distance from your mouth, so your call isn’t muffled or makes you sound like you’re mumbling. I always say that working at a grocery store in high school and having to call for price checks over the intercom prepared me for flying lessons! Put the cell phone away This is one where I can certainly see both sides. Of course, I think more people need to put down their cell phones and interact with each other. In fact, I make it a habit to not immediately 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame get on my cell phone on elevators to avoid awkward silence with the others in the elevator. When other people aren’t on their cell phones, I’ll say hi and make some quick small talk. Try it sometime. You’ll realize how many people get on their phones right away when the doors close. I also understand that this may be the only time that someone can check in with their families, see what the kids are doing, or say hello to someone they really need to talk to. Point is, rather than mindlessly scrolling to pass the time, say hello to the person next to you instead. Dress professionally The way you dress is going to be a bit different based on the type of flying you’re doing. I was surprised to hear several airline pilots say that rather than wearing the required black pants, they’ve seen women wearing black yoga pants instead. Now, trust me. I love yoga pants, but I still don’t think they’re acceptable in a professional setting. If you’re not tied to a uniform in the type of flying you’re doing, make sure you are dressed for needing to hike yourself out of a field should something happen. If you’re a student pilot, you still want to look professional and put together. You never know who you might meet while at your home airport or visiting the FBO on your cross-country flights. This means making sure your hair isn’t a mess, that your nails are groomed, and your clothes are wrinklefree. Nothing says hot mess like looking like you just rolled out of bed. Treat others how you want to be treated There’s always going to be weather, maintenance issues, and other stresses related to flying. Be kind to the ramp personnel, gate agents, front desk staff, van drivers, etc. There really is no excuse for being rude, condescending, or constantly complaining. When you’re talking to those who are trying to help you out, learn their names, be appreciative of

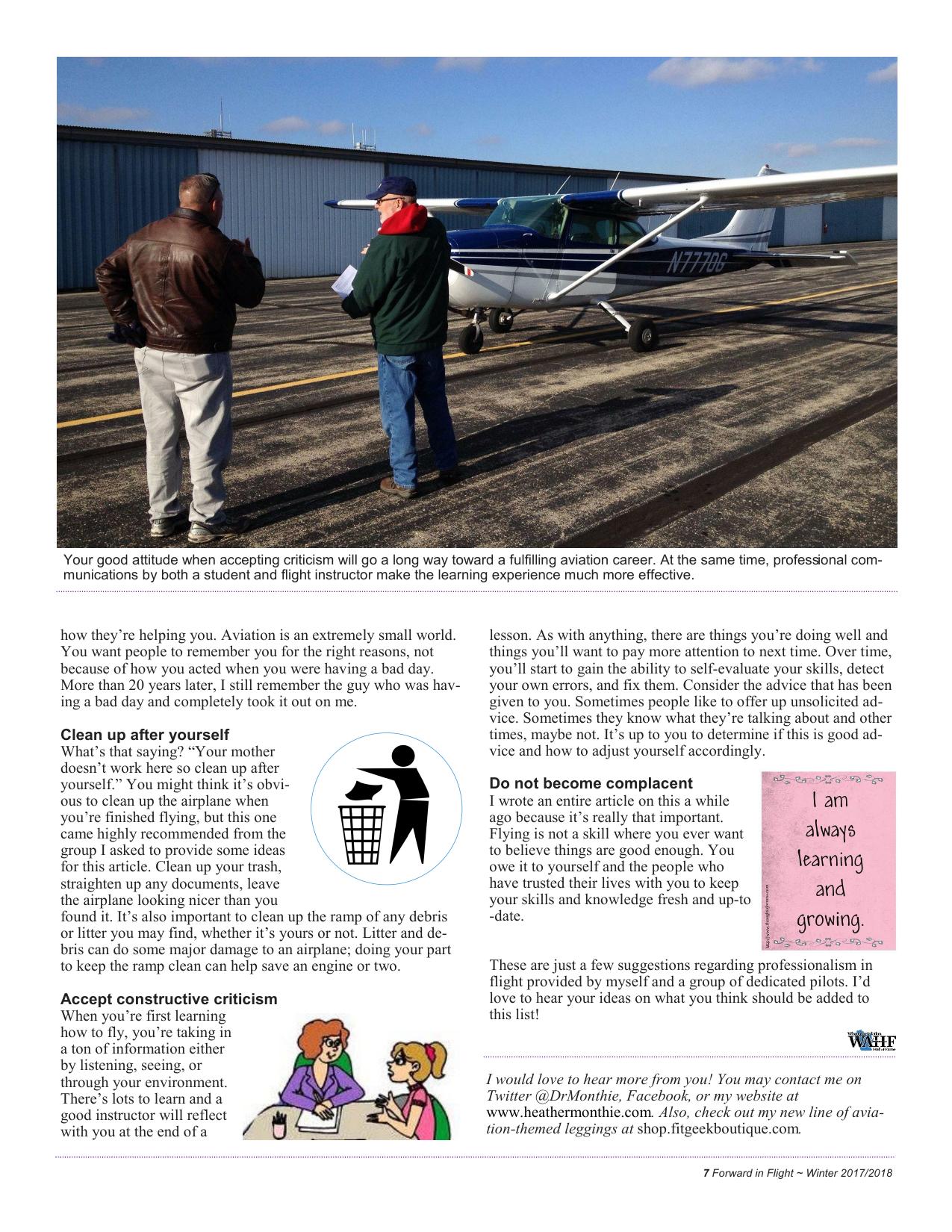

Your good attitude when accepting criticism will go a long way toward a fulfilling aviation career. At the same time, professional communications by both a student and flight instructor make the learning experience much more effective. how they’re helping you. Aviation is an extremely small world. You want people to remember you for the right reasons, not because of how you acted when you were having a bad day. More than 20 years later, I still remember the guy who was having a bad day and completely took it out on me. Clean up after yourself What’s that saying? “Your mother doesn’t work here so clean up after yourself.” You might think it’s obvious to clean up the airplane when you’re finished flying, but this one came highly recommended from the group I asked to provide some ideas for this article. Clean up your trash, straighten up any documents, leave the airplane looking nicer than you found it. It’s also important to clean up the ramp of any debris or litter you may find, whether it’s yours or not. Litter and debris can do some major damage to an airplane; doing your part to keep the ramp clean can help save an engine or two. Accept constructive criticism When you’re first learning how to fly, you’re taking in a ton of information either by listening, seeing, or through your environment. There’s lots to learn and a good instructor will reflect with you at the end of a lesson. As with anything, there are things you’re doing well and things you’ll want to pay more attention to next time. Over time, you’ll start to gain the ability to self-evaluate your skills, detect your own errors, and fix them. Consider the advice that has been given to you. Sometimes people like to offer up unsolicited advice. Sometimes they know what they’re talking about and other times, maybe not. It’s up to you to determine if this is good advice and how to adjust yourself accordingly. Do not become complacent I wrote an entire article on this a while ago because it’s really that important. Flying is not a skill where you ever want to believe things are good enough. You owe it to yourself and the people who have trusted their lives with you to keep your skills and knowledge fresh and up-to -date. These are just a few suggestions regarding professionalism in flight provided by myself and a group of dedicated pilots. I’d love to hear your ideas on what you think should be added to this list! I would love to hear more from you! You may contact me on Twitter @DrMonthie, Facebook, or my website at www.heathermonthie.com. Also, check out my new line of aviation-themed leggings at shop.fitgeekboutique.com. 7 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018

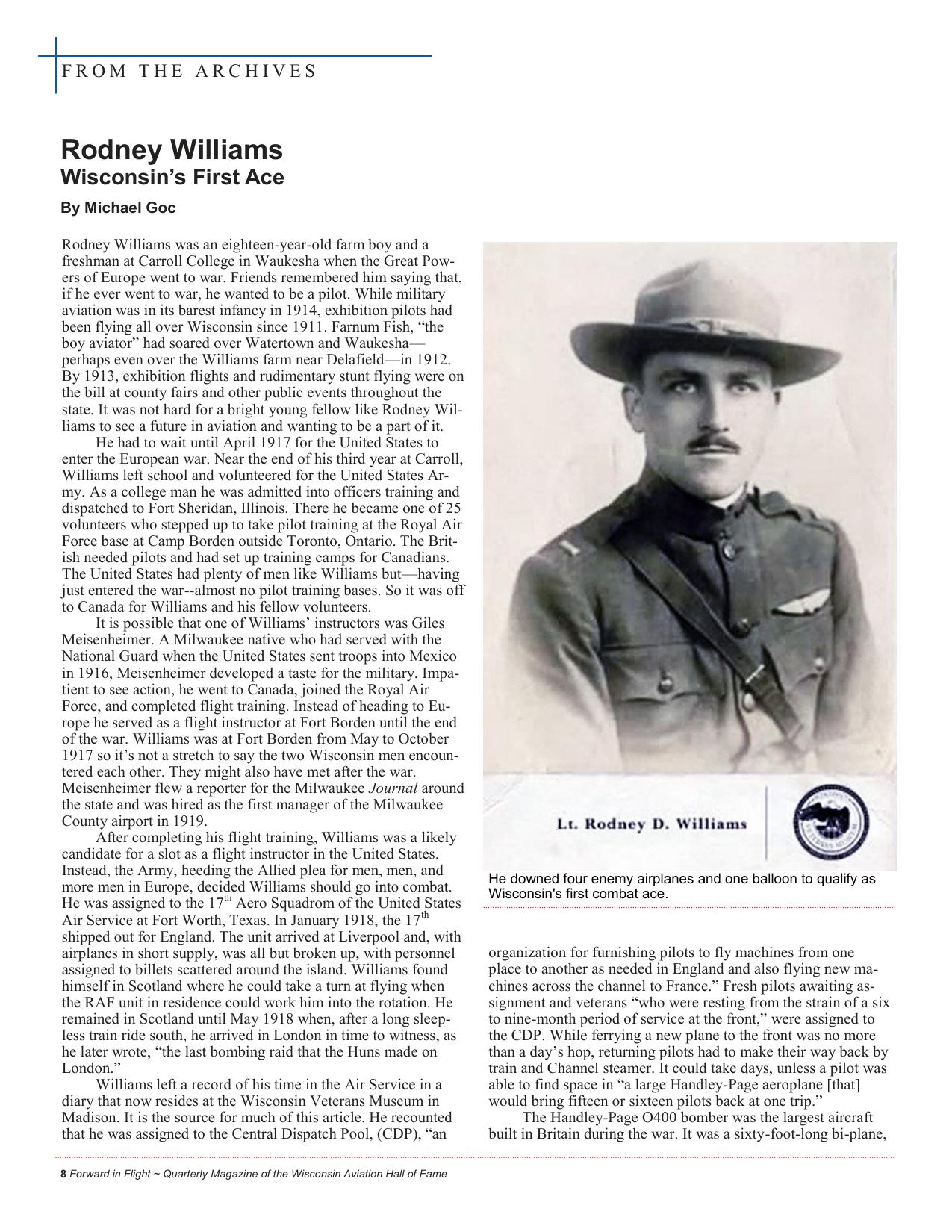

FROM THE ARCHIVES Rodney Williams Wisconsin’s First Ace By Michael Goc Rodney Williams was an eighteen-year-old farm boy and a freshman at Carroll College in Waukesha when the Great Powers of Europe went to war. Friends remembered him saying that, if he ever went to war, he wanted to be a pilot. While military aviation was in its barest infancy in 1914, exhibition pilots had been flying all over Wisconsin since 1911. Farnum Fish, “the boy aviator” had soared over Watertown and Waukesha— perhaps even over the Williams farm near Delafield—in 1912. By 1913, exhibition flights and rudimentary stunt flying were on the bill at county fairs and other public events throughout the state. It was not hard for a bright young fellow like Rodney Williams to see a future in aviation and wanting to be a part of it. He had to wait until April 1917 for the United States to enter the European war. Near the end of his third year at Carroll, Williams left school and volunteered for the United States Army. As a college man he was admitted into officers training and dispatched to Fort Sheridan, Illinois. There he became one of 25 volunteers who stepped up to take pilot training at the Royal Air Force base at Camp Borden outside Toronto, Ontario. The British needed pilots and had set up training camps for Canadians. The United States had plenty of men like Williams but—having just entered the war--almost no pilot training bases. So it was off to Canada for Williams and his fellow volunteers. It is possible that one of Williams’ instructors was Giles Meisenheimer. A Milwaukee native who had served with the National Guard when the United States sent troops into Mexico in 1916, Meisenheimer developed a taste for the military. Impatient to see action, he went to Canada, joined the Royal Air Force, and completed flight training. Instead of heading to Europe he served as a flight instructor at Fort Borden until the end of the war. Williams was at Fort Borden from May to October 1917 so it’s not a stretch to say the two Wisconsin men encountered each other. They might also have met after the war. Meisenheimer flew a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal around the state and was hired as the first manager of the Milwaukee County airport in 1919. After completing his flight training, Williams was a likely candidate for a slot as a flight instructor in the United States. Instead, the Army, heeding the Allied plea for men, men, and more men in Europe, decided Williams should go into combat. He was assigned to the 17th Aero Squadrom of the United States Air Service at Fort Worth, Texas. In January 1918, the 17 th shipped out for England. The unit arrived at Liverpool and, with airplanes in short supply, was all but broken up, with personnel assigned to billets scattered around the island. Williams found himself in Scotland where he could take a turn at flying when the RAF unit in residence could work him into the rotation. He remained in Scotland until May 1918 when, after a long sleepless train ride south, he arrived in London in time to witness, as he later wrote, “the last bombing raid that the Huns made on London.” Williams left a record of his time in the Air Service in a diary that now resides at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum in Madison. It is the source for much of this article. He recounted that he was assigned to the Central Dispatch Pool, (CDP), “an 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame He downed four enemy airplanes and one balloon to qualify as Wisconsin's first combat ace. organization for furnishing pilots to fly machines from one place to another as needed in England and also flying new machines across the channel to France.” Fresh pilots awaiting assignment and veterans “who were resting from the strain of a six to nine-month period of service at the front,” were assigned to the CDP. While ferrying a new plane to the front was no more than a day’s hop, returning pilots had to make their way back by train and Channel steamer. It could take days, unless a pilot was able to find space in “a large Handley-Page aeroplane [that] would bring fifteen or sixteen pilots back at one trip.” The Handley-Page O400 bomber was the largest aircraft built in Britain during the war. It was a sixty-foot-long bi-plane,

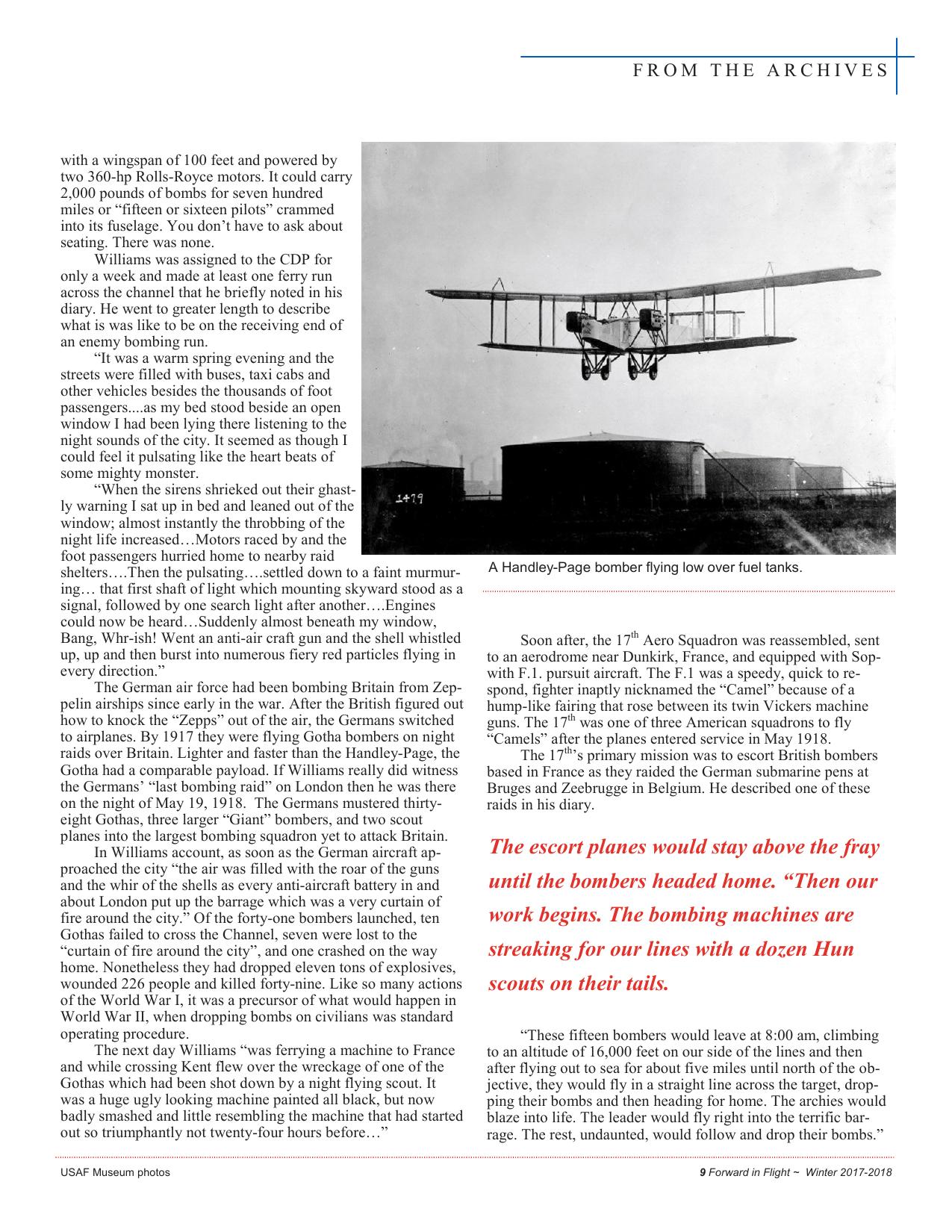

FROM THE ARCHIVES with a wingspan of 100 feet and powered by two 360-hp Rolls-Royce motors. It could carry 2,000 pounds of bombs for seven hundred miles or “fifteen or sixteen pilots” crammed into its fuselage. You don’t have to ask about seating. There was none. Williams was assigned to the CDP for only a week and made at least one ferry run across the channel that he briefly noted in his diary. He went to greater length to describe what is was like to be on the receiving end of an enemy bombing run. “It was a warm spring evening and the streets were filled with buses, taxi cabs and other vehicles besides the thousands of foot passengers....as my bed stood beside an open window I had been lying there listening to the night sounds of the city. It seemed as though I could feel it pulsating like the heart beats of some mighty monster. “When the sirens shrieked out their ghastly warning I sat up in bed and leaned out of the window; almost instantly the throbbing of the night life increased…Motors raced by and the foot passengers hurried home to nearby raid shelters….Then the pulsating….settled down to a faint murmuring… that first shaft of light which mounting skyward stood as a signal, followed by one search light after another….Engines could now be heard…Suddenly almost beneath my window, Bang, Whr-ish! Went an anti-air craft gun and the shell whistled up, up and then burst into numerous fiery red particles flying in every direction.” The German air force had been bombing Britain from Zeppelin airships since early in the war. After the British figured out how to knock the “Zepps” out of the air, the Germans switched to airplanes. By 1917 they were flying Gotha bombers on night raids over Britain. Lighter and faster than the Handley-Page, the Gotha had a comparable payload. If Williams really did witness the Germans’ “last bombing raid” on London then he was there on the night of May 19, 1918. The Germans mustered thirtyeight Gothas, three larger “Giant” bombers, and two scout planes into the largest bombing squadron yet to attack Britain. In Williams account, as soon as the German aircraft approached the city “the air was filled with the roar of the guns and the whir of the shells as every anti-aircraft battery in and about London put up the barrage which was a very curtain of fire around the city.” Of the forty-one bombers launched, ten Gothas failed to cross the Channel, seven were lost to the “curtain of fire around the city”, and one crashed on the way home. Nonetheless they had dropped eleven tons of explosives, wounded 226 people and killed forty-nine. Like so many actions of the World War I, it was a precursor of what would happen in World War II, when dropping bombs on civilians was standard operating procedure. The next day Williams “was ferrying a machine to France and while crossing Kent flew over the wreckage of one of the Gothas which had been shot down by a night flying scout. It was a huge ugly looking machine painted all black, but now badly smashed and little resembling the machine that had started out so triumphantly not twenty-four hours before…” USAF Museum photos A Handley-Page bomber flying low over fuel tanks. Soon after, the 17th Aero Squadron was reassembled, sent to an aerodrome near Dunkirk, France, and equipped with Sopwith F.1. pursuit aircraft. The F.1 was a speedy, quick to respond, fighter inaptly nicknamed the “Camel” because of a hump-like fairing that rose between its twin Vickers machine guns. The 17th was one of three American squadrons to fly “Camels” after the planes entered service in May 1918. The 17th’s primary mission was to escort British bombers based in France as they raided the German submarine pens at Bruges and Zeebrugge in Belgium. He described one of these raids in his diary. The escort planes would stay above the fray until the bombers headed home. “Then our work begins. The bombing machines are streaking for our lines with a dozen Hun scouts on their tails. “These fifteen bombers would leave at 8:00 am, climbing to an altitude of 16,000 feet on our side of the lines and then after flying out to sea for about five miles until north of the objective, they would fly in a straight line across the target, dropping their bombs and then heading for home. The archies would blaze into life. The leader would fly right into the terrific barrage. The rest, undaunted, would follow and drop their bombs.” 9 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017-2018

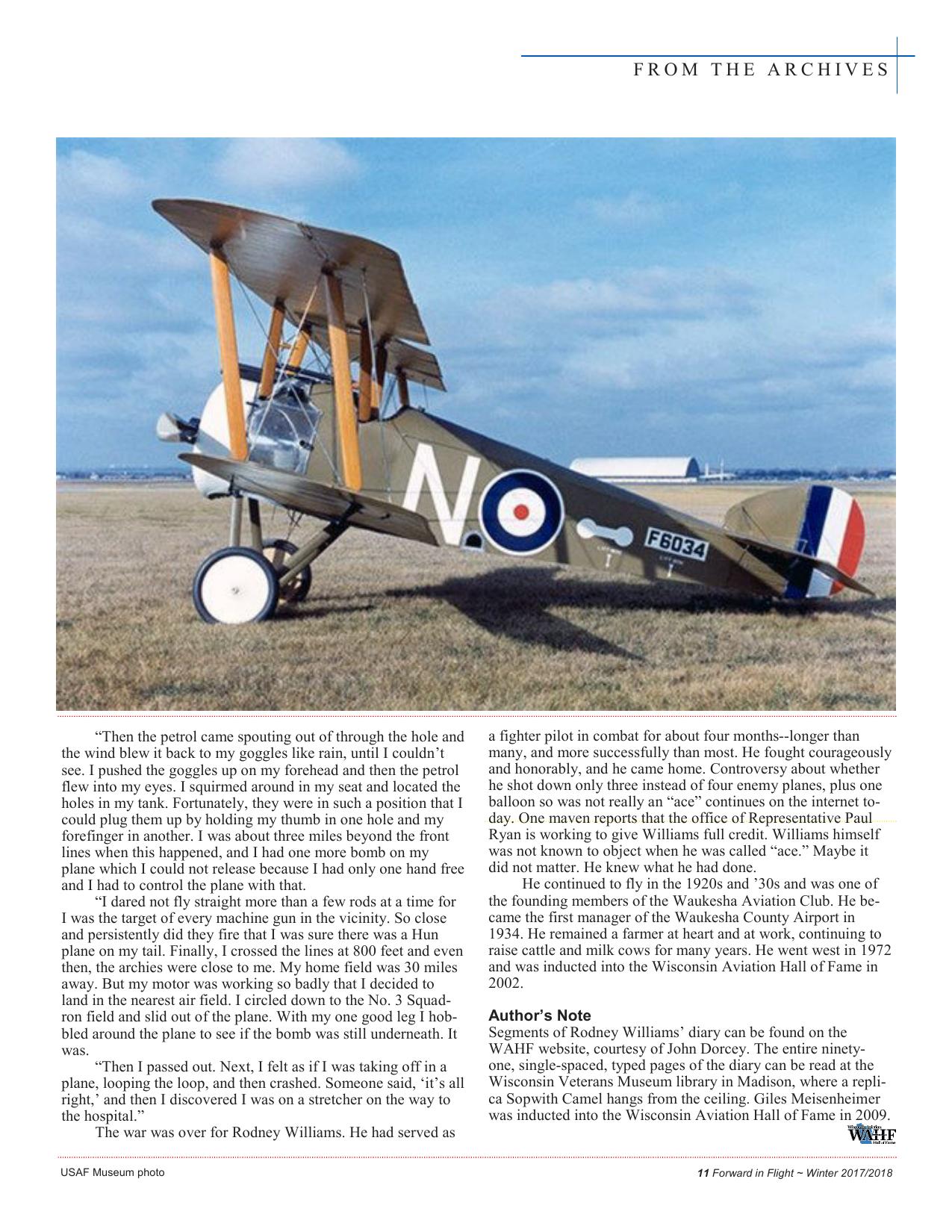

FROM THE ARCHIVES The escort planes would stay above the fray until the bombers headed home. “Then our work begins. The bombing machines are streaking for our lines with a dozen Hun scouts on their tails. Down we dive on the Germans and they scatter, leaving the slow bombers to find their way back home. We fly on the bombers’ tails until they are safely home. Then we retire to the mess to fight the battle all over again.” On one of these missions, Williams became the first pilot in his squadron to score a combat victory. On one of these missions, Williams became the first pilot in his squadron to score a combat victory. He was 17,000 feet above the North Sea port of Ostend in a dogfight with the enemy when his machine guns jammed. He was able to clear the jam and he returned to the battle. Bullets flashed past his cockpit and when he looked back he could just make out an enemy plane diving on him out of the sun. The German roared past and Williams was able to get close on his tail. Twenty-five yards away, Williams fired and knocked the enemy out of the sky. “Any aviator who tells you he was perfectly calm during a dog fight is handling you baloney,” he told a reporter fifteen years later. “All about you is the terrific noise of the motors and the machine guns. The pilot is intensely keyed up, continually looking back to see if an enemy is on his tail. When I used to get back to the field, I’d have a sore neck from watching the rear of my ship.” Sore necks or not, the escort work continued throughout the summer. In August, Williams and five of his squadron mates were returning from a bombing run when they “were attacked by eight enemy planes along the English Channel.” Two of the American pilots had jammed guns and streaked for home. A German plane got on the tail of one of Williams’ mates, dived on it and shot it down. He watched as it “turned crazily and fell into the English Channel.” “Meanwhile, Lieut. Ralph W. Snoke was in the toughest fight I ever saw. Three German planes were diving at him, and Snoke side-slipped and dived like a devil, shooting whenever he could. He was doing some of the best maneuvering I ever saw during the war. I flew to help him, but the Germans withdrew before I got close.” Williams got close enough to down a total of four enemy airplanes and one balloon. He described his balloon busting adventure as if it were a Sunday morning jaunt in the park. “Another pilot and I flew high above the balloon, pretending we were on a mission. Then suddenly we dove straight for the balloon. The observers jumped out in parachutes and the ground men began to pull it down. Down to 100 feet from the bag we came, firing incendiary bullets. Suddenly the whole balloon flamed up and fell to the ground. We zoomed off, closely followed by the archies.” It sounds simpler than it was. On another mission, luck played a major role. Williams was on a scouting patrol inside enemy lines near Lille, when three airplanes of a type he had never seen before appeared out the clouds. At first, he thought they were friendly, but the black crosses on their fuselages soon proved they were enemies. 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame The diving owl insignia of the 17th Aero Squadron. Right: Sopwith F.1. Camel at the United States Air Force Museum, Dayton, Ohio. Outnumbered, Williams attacked. He fired a burst at the first plane but soon found a second on his tail. Hundreds of bullets “whizzed past” but at least one penetrated his primary fuel tank. With fuel leaking and threatening to explode into flames, he feinted and plunged into a fluttering dive for 5,000 feet. The Germans thought he was a goner and hesitated long enough to let him disappear into a cloud bank. Now all he had to deal with was an empty fuel tank. Fortunately, the Sopwith was equipped with a small reserve tank and Williams was not wounded. He managed to get back across the front line and land in a field about five miles from home. When he examined the plane for damage he found dozens of holes in the fuselage and one incendiary bullet lodged in the main fuel tank. It had failed to ignite. He was not quite as lucky, but lucky enough on his last mission. He was ordered to cross enemy lines and reconnoiter movement of transport trucks carrying supplies for an assault on Allied lines. “At 3,000 feet we could see many transports on the roads, so the leader gave us the signal to attack. Each of us picked out a different road and down we went. The road upon which I descended was lined with motor trucks. Diving down to 100 feet I let two bombs go and then zoomed up to see the effect of the explosion. All this while machine guns were firing around me. Also, our own artillery barrage was bursting on the ground directly below me. From one machine gun placement I could see three gunners firing at me. I circled and dropped a bomb on them. Just as I pulled the machine out of the dive, a machine gun bullet came crashing through the petrol tank and then struck me in the hip. There is very little room in the seat of a Camel plane but when that bullet hit me it slammed me against the side of the cockpit as if I had been kicked by a mule. USAF Museum photo

FROM THE ARCHIVES “Then the petrol came spouting out of through the hole and the wind blew it back to my goggles like rain, until I couldn’t see. I pushed the goggles up on my forehead and then the petrol flew into my eyes. I squirmed around in my seat and located the holes in my tank. Fortunately, they were in such a position that I could plug them up by holding my thumb in one hole and my forefinger in another. I was about three miles beyond the front lines when this happened, and I had one more bomb on my plane which I could not release because I had only one hand free and I had to control the plane with that. “I dared not fly straight more than a few rods at a time for I was the target of every machine gun in the vicinity. So close and persistently did they fire that I was sure there was a Hun plane on my tail. Finally, I crossed the lines at 800 feet and even then, the archies were close to me. My home field was 30 miles away. But my motor was working so badly that I decided to land in the nearest air field. I circled down to the No. 3 Squadron field and slid out of the plane. With my one good leg I hobbled around the plane to see if the bomb was still underneath. It was. “Then I passed out. Next, I felt as if I was taking off in a plane, looping the loop, and then crashed. Someone said, ‘it’s all right,’ and then I discovered I was on a stretcher on the way to the hospital.” The war was over for Rodney Williams. He had served as USAF Museum photo a fighter pilot in combat for about four months--longer than many, and more successfully than most. He fought courageously and honorably, and he came home. Controversy about whether he shot down only three instead of four enemy planes, plus one balloon so was not really an “ace” continues on the internet today. One maven reports that the office of Representative Paul Ryan is working to give Williams full credit. Williams himself was not known to object when he was called “ace.” Maybe it did not matter. He knew what he had done. He continued to fly in the 1920s and ’30s and was one of the founding members of the Waukesha Aviation Club. He became the first manager of the Waukesha County Airport in 1934. He remained a farmer at heart and at work, continuing to raise cattle and milk cows for many years. He went west in 1972 and was inducted into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame in 2002. Author’s Note Segments of Rodney Williams’ diary can be found on the WAHF website, courtesy of John Dorcey. The entire ninetyone, single-spaced, typed pages of the diary can be read at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum library in Madison, where a replica Sopwith Camel hangs from the ceiling. Giles Meisenheimer was inducted into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame in 2009. 11 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018

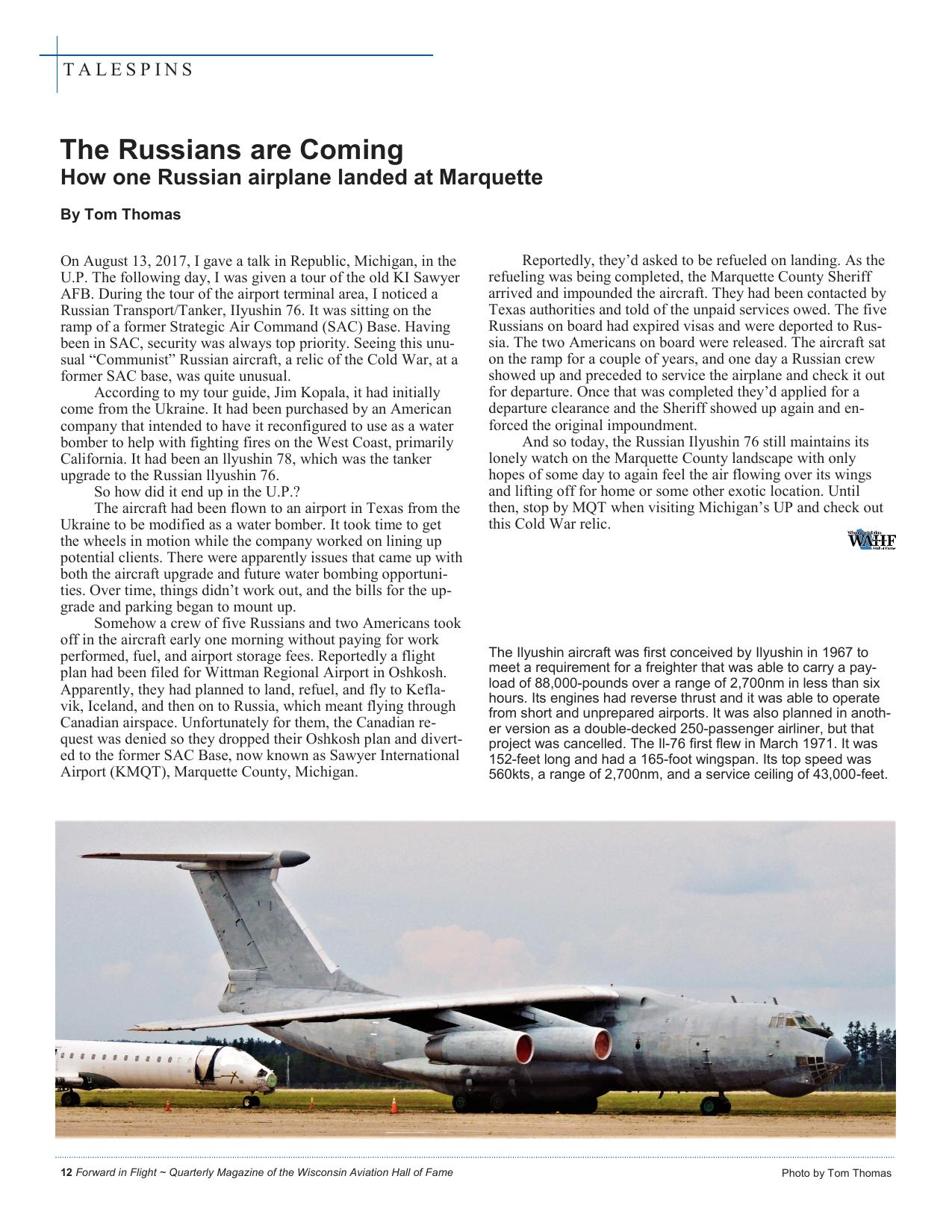

TALESPINS The Russians are Coming How one Russian airplane landed at Marquette By Tom Thomas On August 13, 2017, I gave a talk in Republic, Michigan, in the U.P. The following day, I was given a tour of the old KI Sawyer AFB. During the tour of the airport terminal area, I noticed a Russian Transport/Tanker, IIyushin 76. It was sitting on the ramp of a former Strategic Air Command (SAC) Base. Having been in SAC, security was always top priority. Seeing this unusual “Communist” Russian aircraft, a relic of the Cold War, at a former SAC base, was quite unusual. According to my tour guide, Jim Kopala, it had initially come from the Ukraine. It had been purchased by an American company that intended to have it reconfigured to use as a water bomber to help with fighting fires on the West Coast, primarily California. It had been an llyushin 78, which was the tanker upgrade to the Russian llyushin 76. So how did it end up in the U.P.? The aircraft had been flown to an airport in Texas from the Ukraine to be modified as a water bomber. It took time to get the wheels in motion while the company worked on lining up potential clients. There were apparently issues that came up with both the aircraft upgrade and future water bombing opportunities. Over time, things didn’t work out, and the bills for the upgrade and parking began to mount up. Somehow a crew of five Russians and two Americans took off in the aircraft early one morning without paying for work performed, fuel, and airport storage fees. Reportedly a flight plan had been filed for Wittman Regional Airport in Oshkosh. Apparently, they had planned to land, refuel, and fly to Keflavik, Iceland, and then on to Russia, which meant flying through Canadian airspace. Unfortunately for them, the Canadian request was denied so they dropped their Oshkosh plan and diverted to the former SAC Base, now known as Sawyer International Airport (KMQT), Marquette County, Michigan. 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Reportedly, they’d asked to be refueled on landing. As the refueling was being completed, the Marquette County Sheriff arrived and impounded the aircraft. They had been contacted by Texas authorities and told of the unpaid services owed. The five Russians on board had expired visas and were deported to Russia. The two Americans on board were released. The aircraft sat on the ramp for a couple of years, and one day a Russian crew showed up and preceded to service the airplane and check it out for departure. Once that was completed they’d applied for a departure clearance and the Sheriff showed up again and enforced the original impoundment. And so today, the Russian Ilyushin 76 still maintains its lonely watch on the Marquette County landscape with only hopes of some day to again feel the air flowing over its wings and lifting off for home or some other exotic location. Until then, stop by MQT when visiting Michigan’s UP and check out this Cold War relic. The Ilyushin aircraft was first conceived by Ilyushin in 1967 to meet a requirement for a freighter that was able to carry a payload of 88,000-pounds over a range of 2,700nm in less than six hours. Its engines had reverse thrust and it was able to operate from short and unprepared airports. It was also planned in another version as a double-decked 250-passenger airliner, but that project was cancelled. The Il-76 first flew in March 1971. It was 152-feet long and had a 165-foot wingspan. Its top speed was 560kts, a range of 2,700nm, and a service ceiling of 43,000-feet. Photo by Tom Thomas

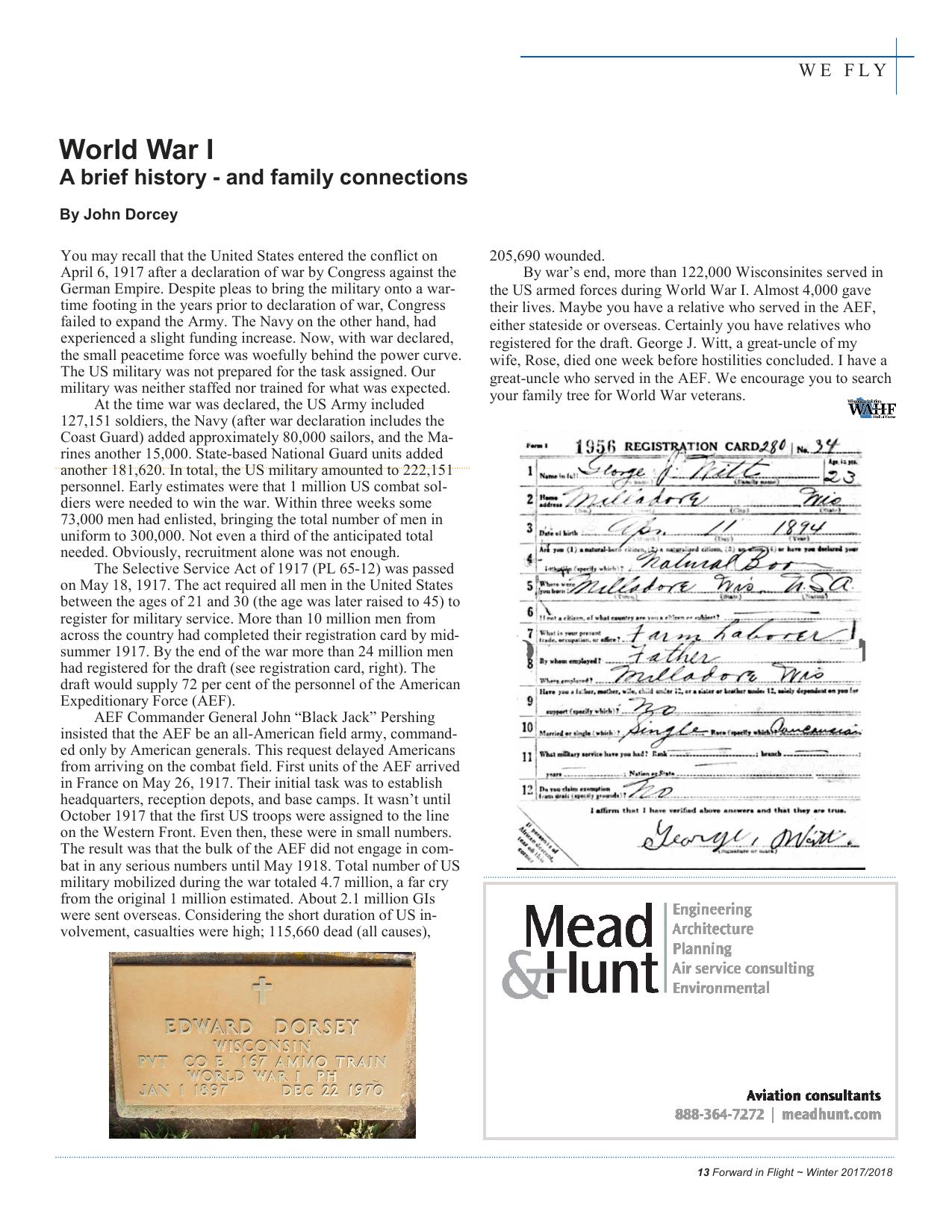

WE FLY World War I A brief history - and family connections By John Dorcey You may recall that the United States entered the conflict on April 6, 1917 after a declaration of war by Congress against the German Empire. Despite pleas to bring the military onto a wartime footing in the years prior to declaration of war, Congress failed to expand the Army. The Navy on the other hand, had experienced a slight funding increase. Now, with war declared, the small peacetime force was woefully behind the power curve. The US military was not prepared for the task assigned. Our military was neither staffed nor trained for what was expected. At the time war was declared, the US Army included 127,151 soldiers, the Navy (after war declaration includes the Coast Guard) added approximately 80,000 sailors, and the Marines another 15,000. State-based National Guard units added another 181,620. In total, the US military amounted to 222,151 personnel. Early estimates were that 1 million US combat soldiers were needed to win the war. Within three weeks some 73,000 men had enlisted, bringing the total number of men in uniform to 300,000. Not even a third of the anticipated total needed. Obviously, recruitment alone was not enough. The Selective Service Act of 1917 (PL 65-12) was passed on May 18, 1917. The act required all men in the United States between the ages of 21 and 30 (the age was later raised to 45) to register for military service. More than 10 million men from across the country had completed their registration card by midsummer 1917. By the end of the war more than 24 million men had registered for the draft (see registration card, right). The draft would supply 72 per cent of the personnel of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). AEF Commander General John “Black Jack” Pershing insisted that the AEF be an all-American field army, commanded only by American generals. This request delayed Americans from arriving on the combat field. First units of the AEF arrived in France on May 26, 1917. Their initial task was to establish headquarters, reception depots, and base camps. It wasn’t until October 1917 that the first US troops were assigned to the line on the Western Front. Even then, these were in small numbers. The result was that the bulk of the AEF did not engage in combat in any serious numbers until May 1918. Total number of US military mobilized during the war totaled 4.7 million, a far cry from the original 1 million estimated. About 2.1 million GIs were sent overseas. Considering the short duration of US involvement, casualties were high; 115,660 dead (all causes), 205,690 wounded. By war’s end, more than 122,000 Wisconsinites served in the US armed forces during World War I. Almost 4,000 gave their lives. Maybe you have a relative who served in the AEF, either stateside or overseas. Certainly you have relatives who registered for the draft. George J. Witt, a great-uncle of my wife, Rose, died one week before hostilities concluded. I have a great-uncle who served in the AEF. We encourage you to search your family tree for World War veterans. 13 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018

2017 Induction Banquet Honoring the finest of Wisconsin aviation Photos by Jessica Voruda and Chris Palmer (unless noted) The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame’s 32nd Annual Investiture Dinner and Ceremony on October 21, 2017 honored a new class of inductees: Donald Cacic, William “Bill” Amorde, Gene Chase, and Charles “Chuck” Swain. More than 200 friends, family, and aviation aficionados attended the event, held in the Founder’s Wing at the EAA Aviation Museum in Oshkosh. A look at the inductees’ aviation careers follows. Donald Richard Cacic Born in 1931, Don moved from Lyons, Illinois, with his family to a farm near Montello, Wisconsin, in March 1946. He learned to fly at LaGrange Field earning his private pilot certificate at age 17. He enlisted in the USAF in 1950. Don first served as a gunner, later becoming an officer and pilot flying the Douglas B-26 Invader, and Boeing B-29 Superfortress. 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Cacic flew as an instructor pilot with the 122nd Bombardment Wing, as part of the 4400th Combat Crew Training Group, Ninth Air Force (TAC) at Langley Air Force Base. On one of his training flights a B-26 had an issue with its nose gear on takeoff, causing the aircraft to cartwheel and catch fire. Don survived with burns, the student did not survive. Don flew two tours during the Korean War flying the B-26 while stationed at Pusan-East Air Base (K-9), South Korea with the 17th Bomb Group, and the North American P-51. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (multiple), Purple Heart, Good Conduct, and the United Nations Service Medals. His military service included time with Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin Air National Guard units. Cacic returned home in 1955 and became active in the Wisconsin Wing of the Civil Air Patrol in 1955. He attained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Don earned the FAA’s Mechanic Certificate with Airframe and Powerplant ratings (A&P) and the Inspection Authorization (IA). In 1989 Don was named airport manager at the Alexander Field-South County Airport (ISW) in Wisconsin Rapids. He ran the FBO providing fuel service, aircraft maintenance, flight instruction, and aircraft rental. He retired in 1999. Over the years Don owned more than 40 aircraft, restoring many of them. Don went west in October 2004. Cacic family photo

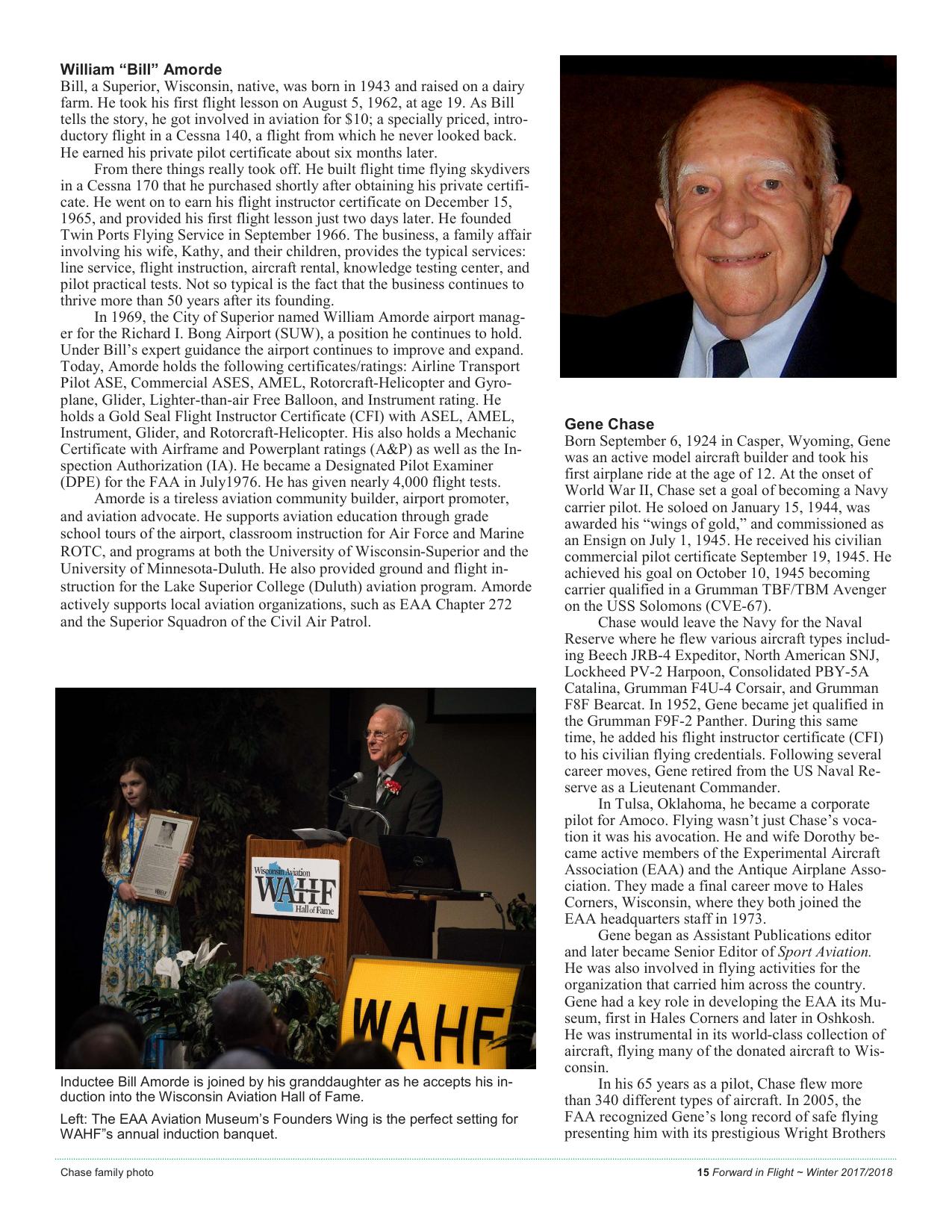

William “Bill” Amorde Bill, a Superior, Wisconsin, native, was born in 1943 and raised on a dairy farm. He took his first flight lesson on August 5, 1962, at age 19. As Bill tells the story, he got involved in aviation for $10; a specially priced, introductory flight in a Cessna 140, a flight from which he never looked back. He earned his private pilot certificate about six months later. From there things really took off. He built flight time flying skydivers in a Cessna 170 that he purchased shortly after obtaining his private certificate. He went on to earn his flight instructor certificate on December 15, 1965, and provided his first flight lesson just two days later. He founded Twin Ports Flying Service in September 1966. The business, a family affair involving his wife, Kathy, and their children, provides the typical services: line service, flight instruction, aircraft rental, knowledge testing center, and pilot practical tests. Not so typical is the fact that the business continues to thrive more than 50 years after its founding. In 1969, the City of Superior named William Amorde airport manager for the Richard I. Bong Airport (SUW), a position he continues to hold. Under Bill’s expert guidance the airport continues to improve and expand. Today, Amorde holds the following certificates/ratings: Airline Transport Pilot ASE, Commercial ASES, AMEL, Rotorcraft-Helicopter and Gyroplane, Glider, Lighter-than-air Free Balloon, and Instrument rating. He holds a Gold Seal Flight Instructor Certificate (CFI) with ASEL, AMEL, Instrument, Glider, and Rotorcraft-Helicopter. His also holds a Mechanic Certificate with Airframe and Powerplant ratings (A&P) as well as the Inspection Authorization (IA). He became a Designated Pilot Examiner (DPE) for the FAA in July1976. He has given nearly 4,000 flight tests. Amorde is a tireless aviation community builder, airport promoter, and aviation advocate. He supports aviation education through grade school tours of the airport, classroom instruction for Air Force and Marine ROTC, and programs at both the University of Wisconsin-Superior and the University of Minnesota-Duluth. He also provided ground and flight instruction for the Lake Superior College (Duluth) aviation program. Amorde actively supports local aviation organizations, such as EAA Chapter 272 and the Superior Squadron of the Civil Air Patrol. Inductee Bill Amorde is joined by his granddaughter as he accepts his induction into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. Left: The EAA Aviation Museum’s Founders Wing is the perfect setting for WAHF”s annual induction banquet. Chase family photo Gene Chase Born September 6, 1924 in Casper, Wyoming, Gene was an active model aircraft builder and took his first airplane ride at the age of 12. At the onset of World War II, Chase set a goal of becoming a Navy carrier pilot. He soloed on January 15, 1944, was awarded his “wings of gold,” and commissioned as an Ensign on July 1, 1945. He received his civilian commercial pilot certificate September 19, 1945. He achieved his goal on October 10, 1945 becoming carrier qualified in a Grumman TBF/TBM Avenger on the USS Solomons (CVE-67). Chase would leave the Navy for the Naval Reserve where he flew various aircraft types including Beech JRB-4 Expeditor, North American SNJ, Lockheed PV-2 Harpoon, Consolidated PBY-5A Catalina, Grumman F4U-4 Corsair, and Grumman F8F Bearcat. In 1952, Gene became jet qualified in the Grumman F9F-2 Panther. During this same time, he added his flight instructor certificate (CFI) to his civilian flying credentials. Following several career moves, Gene retired from the US Naval Reserve as a Lieutenant Commander. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, he became a corporate pilot for Amoco. Flying wasn’t just Chase’s vocation it was his avocation. He and wife Dorothy became active members of the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) and the Antique Airplane Association. They made a final career move to Hales Corners, Wisconsin, where they both joined the EAA headquarters staff in 1973. Gene began as Assistant Publications editor and later became Senior Editor of Sport Aviation. He was also involved in flying activities for the organization that carried him across the country. Gene had a key role in developing the EAA its Museum, first in Hales Corners and later in Oshkosh. He was instrumental in its world-class collection of aircraft, flying many of the donated aircraft to Wisconsin. In his 65 years as a pilot, Chase flew more than 340 different types of aircraft. In 2005, the FAA recognized Gene’s long record of safe flying presenting him with its prestigious Wright Brothers 15 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018

Master Pilot Award. He has been personally involved with the restoration of several vintage aircraft including his own Davis D -1-W. He served on the Board of Directors of the Vintage Aircraft Association. Gene Chase served as a distinguished military aviator, corporate pilot, flight instructor, aviation museum director, author, restorer of vintage aircraft, and editor of aviation publications. Passing away in January 2017, Gene’s lifetime devotion to aviation has and will continue to inspire countless others. Charles Swain Born in 1946 and raised in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, Charles always had an interest in aviation. He joined the Dodge County Squadron of the USAF Auxiliary-Civil Air Patrol and rose through the ranks to become a cadet officer and commander of the cadet squadron. Upon graduating from Wayland Academy, he attended Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University (Daytona Beach) earning a Bachelor of Science degree in Aviation Maintenance. Today, Swain holds an Aircraft Mechanic Certificate with Airframe and Powerplant ratings (A&P) and the Inspection Authorization (IA). His first job out of school was with Boeing Aircraft. Chuck soon learned however that Boeing was cutting back; he received his first check and his furlough notice at the same time. His second job in aviation soon followed as an aircraft mechanic with Delta Airlines at Chicago O’Hare (ORD). About this same time, he married Tina Spangler. As oft times happen, children soon entered the picture and the urge to return home was too strong to ignore. The Swains returned home to Beaver Dam and eventually there were five: Chuck, Tina, Charles Jr, Andy, and Molly. Swain went to work for Paul Baker, founder/owner of Beaver Aviation, located at Dodge County Airport, Juneau, Wisconsin (KUNU). Paul mentored Chuck and after working together for a few years Chuck purchased Beaver Aviation in 1975. Chuck trained with WAHF inductee Roy Reabe and earned his Private Pilot Certificate. He owned a Piper Tri-Pacer until he and Tina realized they couldn’t raise a family in an airplane, so he sold it in favor of their house. After 30 years in business, Swain sold Beaver Aviation to Eric Nelson in 2005, but he still works there part-time. Swain is not one to sit back and watch the world go by. He participates and gives of his time and talents when and where he can make an impact. After getting reestablished at home in Beaver Dam, Chuck was elected a County Board Supervisor and then County Board Chair. He served on numerous committees and chaired some of them. He is an active and long-time member of the Beaver Dam Kiwanis. Swain became an FAA Accident Prevention Counselor and was a long-time member of Wisconsin Bureau of Aeronautics Conference Planning Committee. The Governor appointed him to a special accident investigation committee and another committee to design the overhaul of the State of Wisconsin Air Services. Chuck was a member of the Wisconsin Aviation Trades Association (WATA) becoming a board member and eventually chairman. He is a supporter of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame and in 2005 was elected to serve on its board. Chuck continues to provide guidance, counsel, professionalism, and labor to the aviation industry. All of aviation is better for it. 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Submitted and Jessica Voruda/Chris Palmer photos

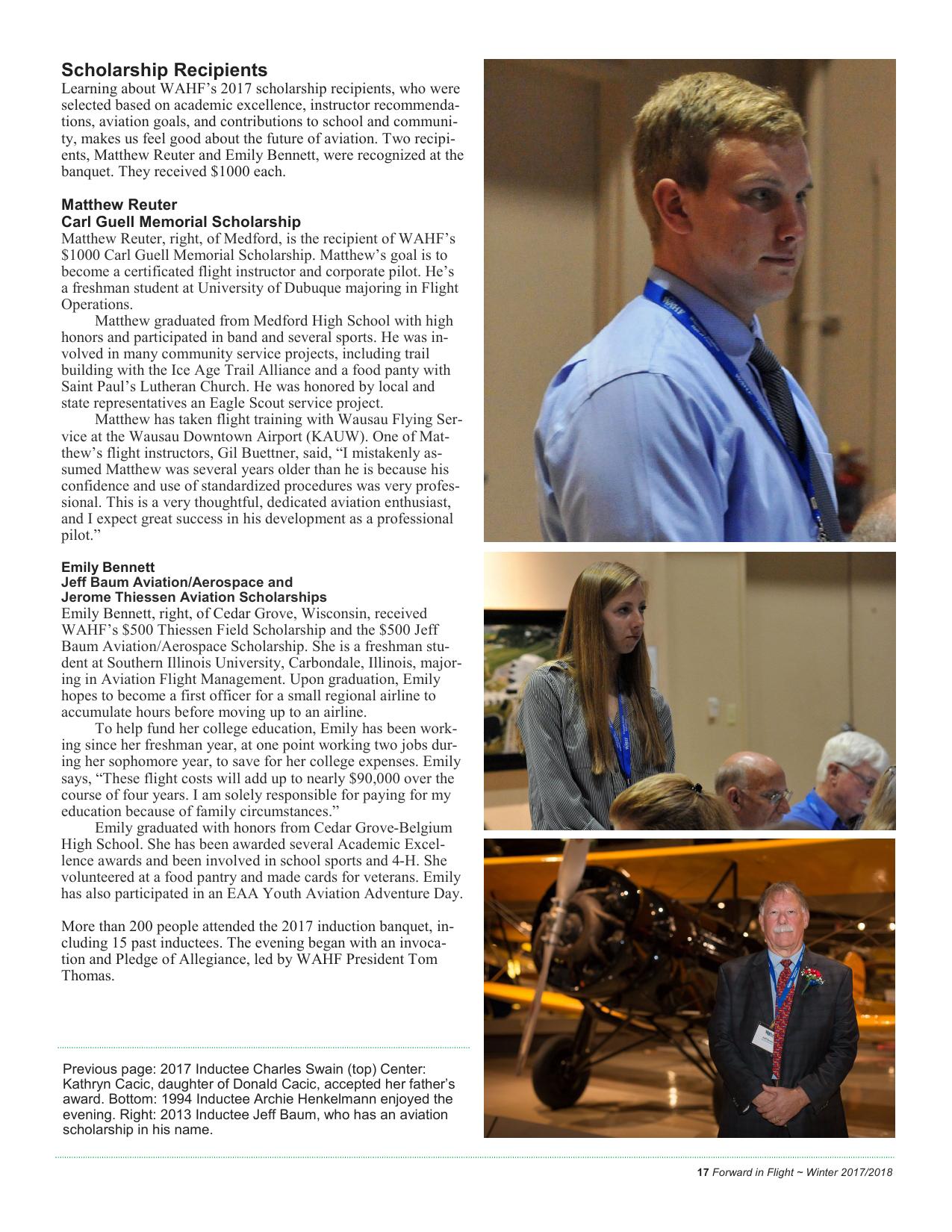

Scholarship Recipients Learning about WAHF’s 2017 scholarship recipients, who were selected based on academic excellence, instructor recommendations, aviation goals, and contributions to school and community, makes us feel good about the future of aviation. Two recipients, Matthew Reuter and Emily Bennett, were recognized at the banquet. They received $1000 each. Matthew Reuter Carl Guell Memorial Scholarship Matthew Reuter, right, of Medford, is the recipient of WAHF’s $1000 Carl Guell Memorial Scholarship. Matthew’s goal is to become a certificated flight instructor and corporate pilot. He’s a freshman student at University of Dubuque majoring in Flight Operations. Matthew graduated from Medford High School with high honors and participated in band and several sports. He was involved in many community service projects, including trail building with the Ice Age Trail Alliance and a food panty with Saint Paul’s Lutheran Church. He was honored by local and state representatives an Eagle Scout service project. Matthew has taken flight training with Wausau Flying Service at the Wausau Downtown Airport (KAUW). One of Matthew’s flight instructors, Gil Buettner, said, “I mistakenly assumed Matthew was several years older than he is because his confidence and use of standardized procedures was very professional. This is a very thoughtful, dedicated aviation enthusiast, and I expect great success in his development as a professional pilot.” Emily Bennett Jeff Baum Aviation/Aerospace and Jerome Thiessen Aviation Scholarships Emily Bennett, right, of Cedar Grove, Wisconsin, received WAHF’s $500 Thiessen Field Scholarship and the $500 Jeff Baum Aviation/Aerospace Scholarship. She is a freshman student at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, majoring in Aviation Flight Management. Upon graduation, Emily hopes to become a first officer for a small regional airline to accumulate hours before moving up to an airline. To help fund her college education, Emily has been working since her freshman year, at one point working two jobs during her sophomore year, to save for her college expenses. Emily says, “These flight costs will add up to nearly $90,000 over the course of four years. I am solely responsible for paying for my education because of family circumstances.” Emily graduated with honors from Cedar Grove-Belgium High School. She has been awarded several Academic Excellence awards and been involved in school sports and 4-H. She volunteered at a food pantry and made cards for veterans. Emily has also participated in an EAA Youth Aviation Adventure Day. More than 200 people attended the 2017 induction banquet, including 15 past inductees. The evening began with an invocation and Pledge of Allegiance, led by WAHF President Tom Thomas. Previous page: 2017 Inductee Charles Swain (top) Center: Kathryn Cacic, daughter of Donald Cacic, accepted her father’s award. Bottom: 1994 Inductee Archie Henkelmann enjoyed the evening. Right: 2013 Inductee Jeff Baum, who has an aviation scholarship in his name. 17 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018

Clockwise from top left: WAHF Board Member Ron Wojnar presented the Gene Chase induction. Catching up on life were Jeanne Thomas and 2010 WAHF Inductee Bob Kunkel, who now resides in Texas. Next page: Duane Esse, an inductee in 2005, found much to discuss at the banquet. At 104, 2009 Inductee Paul Johns was all smiles at the banquet. Robert Clarke, 2006, posed for a formal shot. Harold “Duffy” Gaier, inducted in 2009, enjoyed the evening with family and friends. WAHF President Tom Thomas closed the evening with a prayer. 18 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Bill “Mr. Pietenpol” Rewey, posed with his favorite aircraft. Photos by Chris Palmer and Jessica Voruda

19 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018

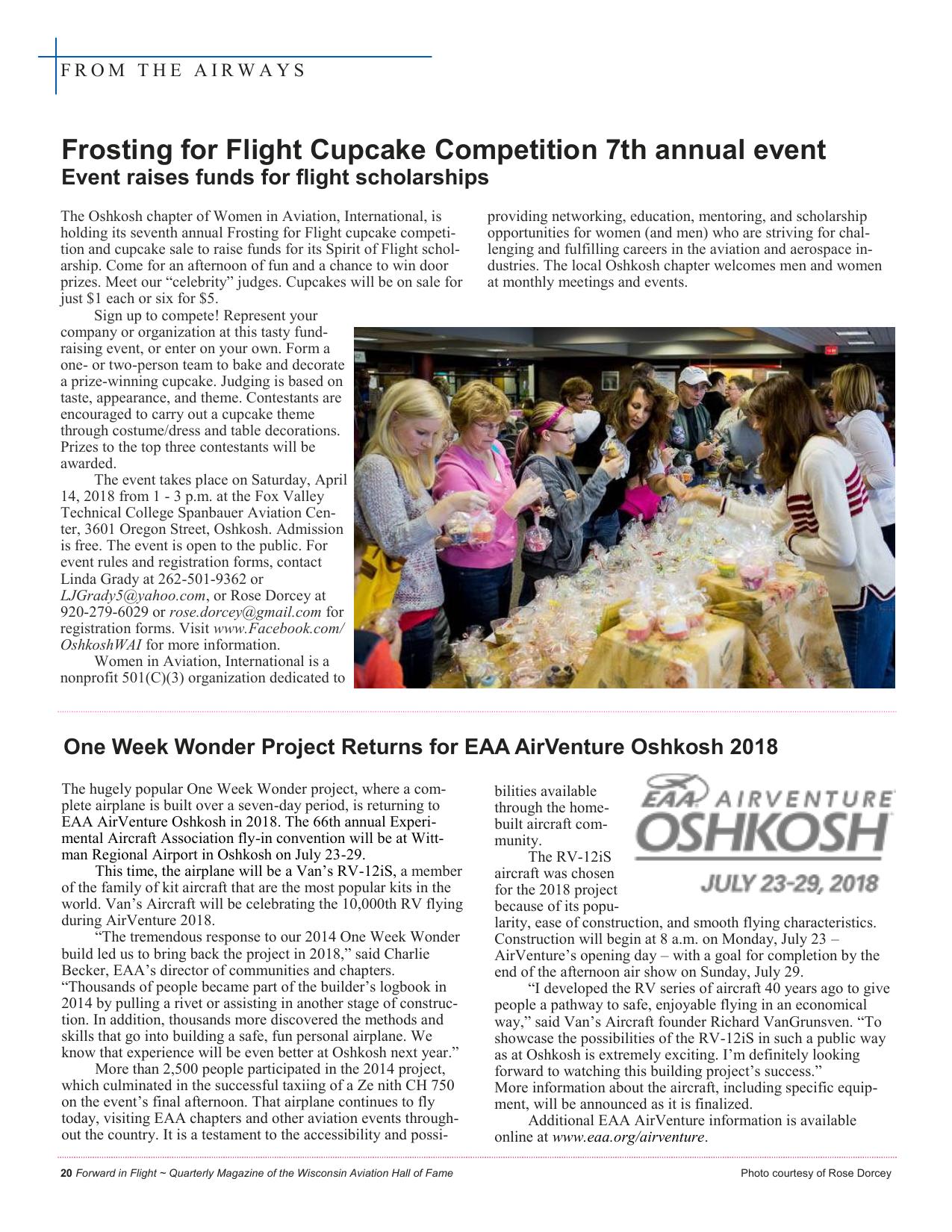

FROM THE AIRWAYS Frosting for Flight Cupcake Competition 7th annual event Event raises funds for flight scholarships The Oshkosh chapter of Women in Aviation, International, is holding its seventh annual Frosting for Flight cupcake competition and cupcake sale to raise funds for its Spirit of Flight scholarship. Come for an afternoon of fun and a chance to win door prizes. Meet our “celebrity” judges. Cupcakes will be on sale for just $1 each or six for $5. Sign up to compete! Represent your company or organization at this tasty fundraising event, or enter on your own. Form a one- or two-person team to bake and decorate a prize-winning cupcake. Judging is based on taste, appearance, and theme. Contestants are encouraged to carry out a cupcake theme through costume/dress and table decorations. Prizes to the top three contestants will be awarded. The event takes place on Saturday, April 14, 2018 from 1 - 3 p.m. at the Fox Valley Technical College Spanbauer Aviation Center, 3601 Oregon Street, Oshkosh. Admission is free. The event is open to the public. For event rules and registration forms, contact Linda Grady at 262-501-9362 or LJGrady5@yahoo.com, or Rose Dorcey at 920-279-6029 or rose.dorcey@gmail.com for registration forms. Visit www.Facebook.com/ OshkoshWAI for more information. Women in Aviation, International is a nonprofit 501(C)(3) organization dedicated to providing networking, education, mentoring, and scholarship opportunities for women (and men) who are striving for challenging and fulfilling careers in the aviation and aerospace industries. The local Oshkosh chapter welcomes men and women at monthly meetings and events. One Week Wonder Project Returns for EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2018 The hugely popular One Week Wonder project, where a complete airplane is built over a seven-day period, is returning to EAA AirVenture Oshkosh in 2018. The 66th annual Experimental Aircraft Association fly-in convention will be at Wittman Regional Airport in Oshkosh on July 23-29. This time, the airplane will be a Van’s RV-12iS, a member of the family of kit aircraft that are the most popular kits in the world. Van’s Aircraft will be celebrating the 10,000th RV flying during AirVenture 2018. “The tremendous response to our 2014 One Week Wonder build led us to bring back the project in 2018,” said Charlie Becker, EAA’s director of communities and chapters. “Thousands of people became part of the builder’s logbook in 2014 by pulling a rivet or assisting in another stage of construction. In addition, thousands more discovered the methods and skills that go into building a safe, fun personal airplane. We know that experience will be even better at Oshkosh next year.” More than 2,500 people participated in the 2014 project, which culminated in the successful taxiing of a Ze nith CH 750 on the event’s final afternoon. That airplane continues to fly today, visiting EAA chapters and other aviation events throughout the country. It is a testament to the accessibility and possi20 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame bilities available through the homebuilt aircraft community. The RV-12iS aircraft was chosen for the 2018 project because of its popularity, ease of construction, and smooth flying characteristics. Construction will begin at 8 a.m. on Monday, July 23 – AirVenture’s opening day – with a goal for completion by the end of the afternoon air show on Sunday, July 29. “I developed the RV series of aircraft 40 years ago to give people a pathway to safe, enjoyable flying in an economical way,” said Van’s Aircraft founder Richard VanGrunsven. “To showcase the possibilities of the RV-12iS in such a public way as at Oshkosh is extremely exciting. I’m definitely looking forward to watching this building project’s success.” More information about the aircraft, including specific equipment, will be announced as it is finalized. Additional EAA AirVenture information is available online at www.eaa.org/airventure. Photo courtesy of Rose Dorcey

FROM THE AIRWAYS Wisconsin Airport Management Association News Aviation awards and 63rd annual conference planning The Wisconsin Airport Management Association is seeking nominations for its 2018 WAMA Aviation Awards. To nominate a person or project submit an online Award Nomination Form. Your nomination must be submitted before March 16, 2018. Award winners will be recognized at the 2018 Wisconsin Aviation Conference. To view past aviation award recipients, click on the award name below: · Distinguished Service Award - Awarded to the persons who have made an outstanding contribution to aviation. · Blue Light Award - Awarded to persons in the media who have distinguished themselves by their excellent reporting on Wisconsin Aviation. · Person of the Year Award - Awarded to persons who have distinguished themselves in Wisconsin Aviation during the past calendar year. · Lifetime Service Award - Awarded to persons who have devoted themselves to promoting and serving Wisconsin aviation for at least ten years. · Airport Engineering Award - Awarded to persons who have made significant professional contributions in the airport engineering or architecture fields in Wisconsin. Registration is now open for the 63rd annual Wisconsin Aviation Conference. Taking place at the Wilderness Hotel and Golf Resort May 6 - 8, the conference will be filled with timely topics for all attendees including Wisconsin airports, consultants, and representatives from the state and FAA. The WAC planning committee is excited for its new conference format. It opens on Sunday with sporting clays and golfing available. Conference attendees are encouraged to bring their families to enjoy all the Wilderness Hotel has to offer. Monday and Tuesday of the conference will once again feature speed dating with the FAA Chicago Airport District Office personnel. Speed Dating is your opportunity as an airport sponsor to meet face-to-face with representatives of the Chicago Airports District Office (ADO) about issues specific to YOUR Airport. You must sign up in advance to schedule/reserve an appointment; appointments are limited. Contact Bob O’Brien for details (608-739-2011). Space is limited. For more information visit www.WIAMA.org. EAA’s Jack Pelton Receives Honors Jack J. Pelton, CEO and chairman of the board for the Experimental Aircraft Association, received multiple honors recently from the National Aeronautic Association, Federal Aviation Administration, and the Kansas Aviation Hall of Fame. Pelton was named one of six 2017 recipients of NAA’s Wesley McDonald Distinguished Statesman of Aviation Award. The award recognizes “outstanding living Americans who, by their efforts over an extended period of years, have made contributions of significant value to aeronautics, and have reflected credit upon America and themselves.” Pelton received that award during NAA’s annual fall awards program on November 29, 2017 in Arlington, Virginia. On November 28, Pelton received the Friend of Safety Award from the FAA’s Aviation Safety organization. It honored Pelton’s leadership in developing low-cost, safety-enhancing equipment for general aviation cockpits. Those awards followed Pelton’s November 11 induction into the Kansas Aviation Hall of Fame, which recognizes Kansas citizens who have made contributions to aviation of statewide or national significance. Along with his leadership of EAA, Pelton was recognized for his tenure as president, CEO, and chairman of Cessna Aircraft Company. Pelton first headed EAA in October 2012, serving in a volunteer role as chairman of the board and providing transition leadership for a three-year period. The EAA board then named him CEO/chairman, a fulltime position, in November 2015. Share Your News with WAHF Your business or personal news is of interest to us, and our readers. Please submit your news, and appropriate photo(s), to Rose Dorcey at rose.dorcey@gmail.com. Photo courtesy of EAA 21 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2017/2018