Forward in Flight - Winter 2020

Volume 18, Issue 4 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Winter 2020-2021

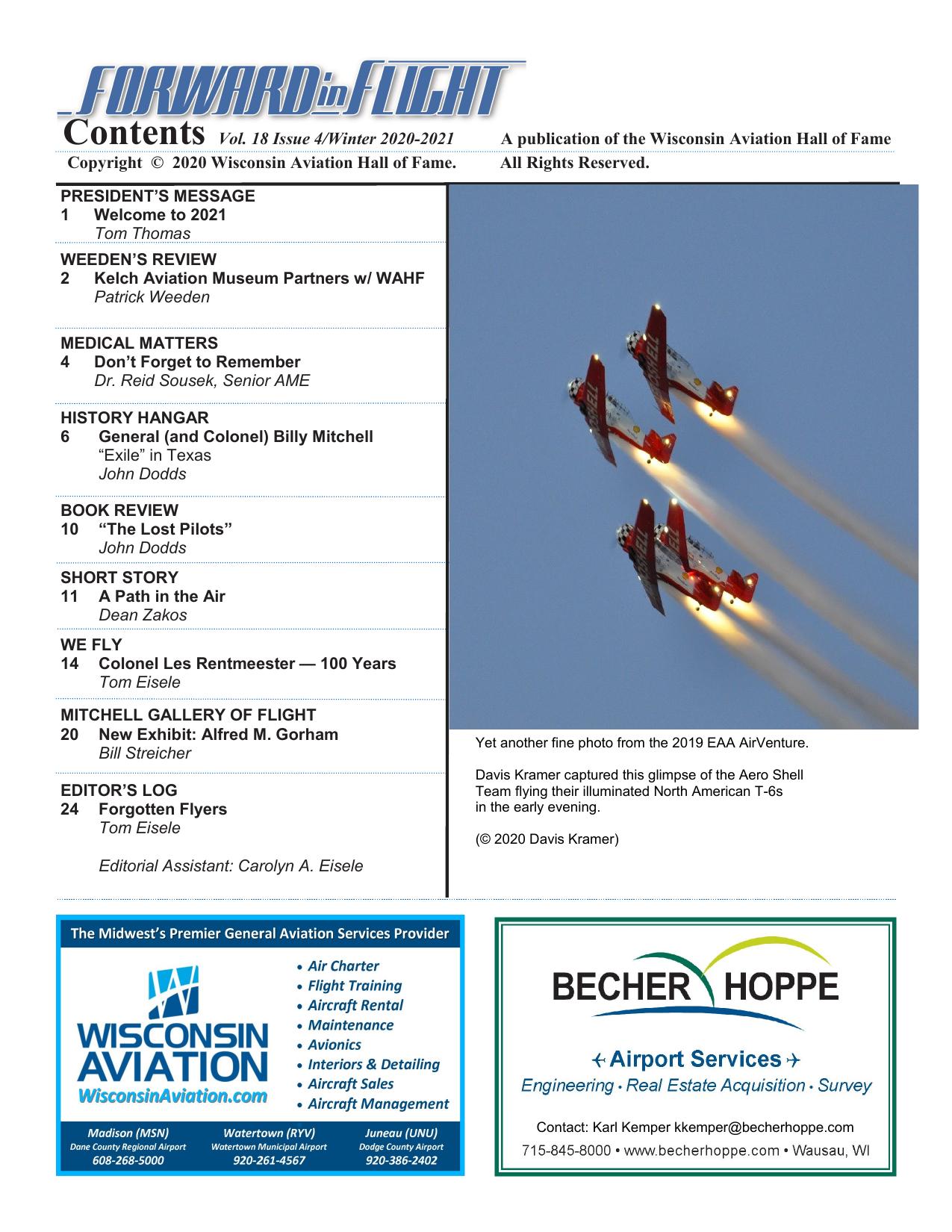

Contents Vol. 18 Issue 4/Winter 2020-2021 Copyright © 2020 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All Rights Reserved. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 1 Welcome to 2021 Tom Thomas WEEDEN’S REVIEW 2 Kelch Aviation Museum Partners w/ WAHF Patrick Weeden MEDICAL MATTERS 4 Don’t Forget to Remember Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME HISTORY HANGAR 6 General (and Colonel) Billy Mitchell “Exile” in Texas John Dodds BOOK REVIEW 10 “The Lost Pilots” John Dodds SHORT STORY 11 A Path in the Air Dean Zakos WE FLY 14 Colonel Les Rentmeester — 100 Years Tom Eisele MITCHELL GALLERY OF FLIGHT 20 New Exhibit: Alfred M. Gorham Bill Streicher EDITOR’S LOG 24 Forgotten Flyers Tom Eisele Yet another fine photo from the 2019 EAA AirVenture. Davis Kramer captured this glimpse of the Aero Shell Team flying their illuminated North American T-6s in the early evening. (© 2020 Davis Kramer) Editorial Assistant: Carolyn A. Eisele Contact: Karl Kemper kkemper@becherhoppe.com

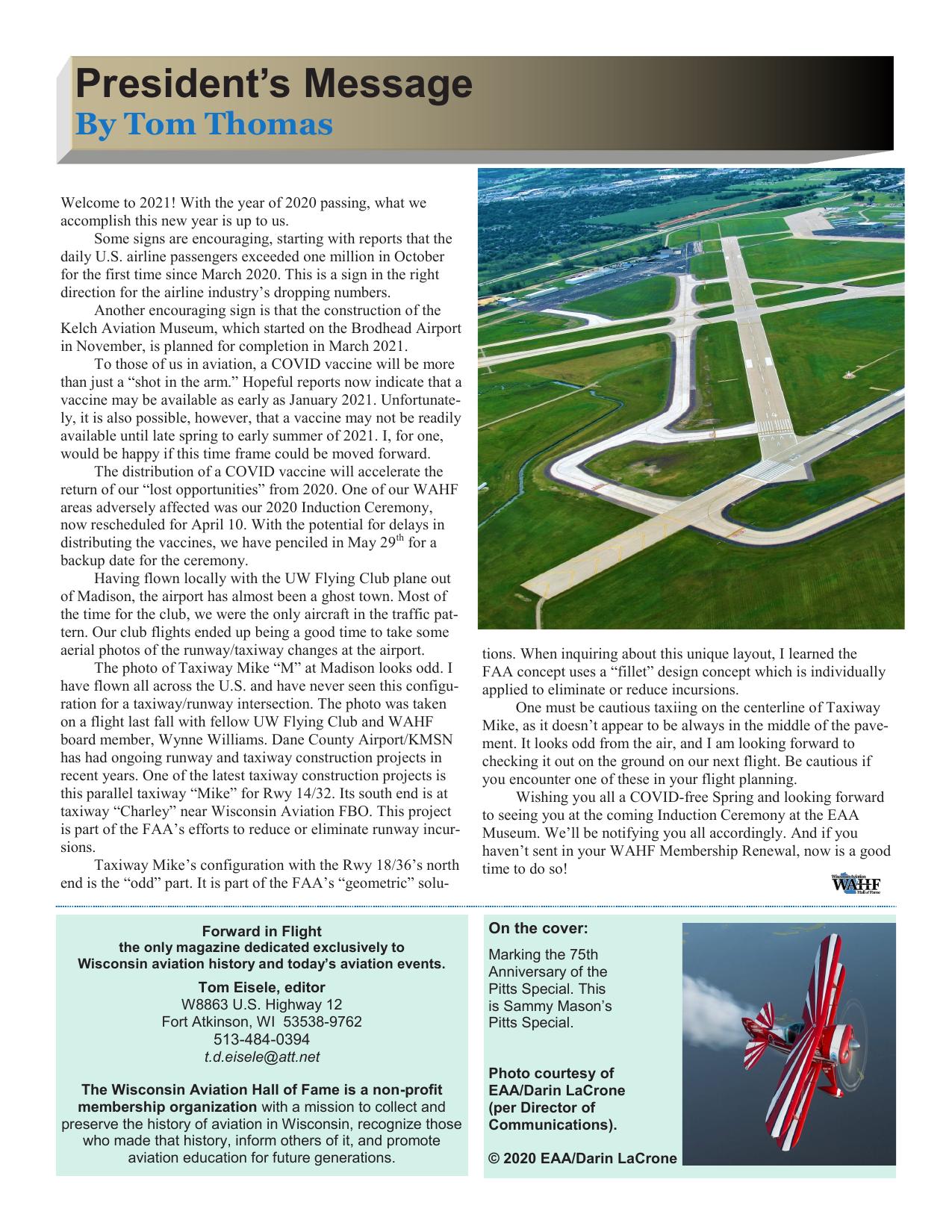

President’s Message By Tom Thomas Welcome to 2021! With the year of 2020 passing, what we accomplish this new year is up to us. Some signs are encouraging, starting with reports that the daily U.S. airline passengers exceeded one million in October for the first time since March 2020. This is a sign in the right direction for the airline industry’s dropping numbers. Another encouraging sign is that the construction of the Kelch Aviation Museum, which started on the Brodhead Airport in November, is planned for completion in March 2021. To those of us in aviation, a COVID vaccine will be more than just a “shot in the arm.” Hopeful reports now indicate that a vaccine may be available as early as January 2021. Unfortunately, it is also possible, however, that a vaccine may not be readily available until late spring to early summer of 2021. I, for one, would be happy if this time frame could be moved forward. The distribution of a COVID vaccine will accelerate the return of our “lost opportunities” from 2020. One of our WAHF areas adversely affected was our 2020 Induction Ceremony, now rescheduled for April 10. With the potential for delays in distributing the vaccines, we have penciled in May 29th for a backup date for the ceremony. Having flown locally with the UW Flying Club plane out of Madison, the airport has almost been a ghost town. Most of the time for the club, we were the only aircraft in the traffic pattern. Our club flights ended up being a good time to take some aerial photos of the runway/taxiway changes at the airport. The photo of Taxiway Mike “M” at Madison looks odd. I have flown all across the U.S. and have never seen this configuration for a taxiway/runway intersection. The photo was taken on a flight last fall with fellow UW Flying Club and WAHF board member, Wynne Williams. Dane County Airport/KMSN has had ongoing runway and taxiway construction projects in recent years. One of the latest taxiway construction projects is this parallel taxiway “Mike” for Rwy 14/32. Its south end is at taxiway “Charley” near Wisconsin Aviation FBO. This project is part of the FAA’s efforts to reduce or eliminate runway incursions. Taxiway Mike’s configuration with the Rwy 18/36’s north end is the “odd” part. It is part of the FAA’s “geometric” soluForward in Flight the only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s aviation events. Tom Eisele, editor W8863 U.S. Highway 12 Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-9762 513-484-0394 tions. When inquiring about this unique layout, I learned the FAA concept uses a “fillet” design concept which is individually applied to eliminate or reduce incursions. One must be cautious taxiing on the centerline of Taxiway Mike, as it doesn’t appear to be always in the middle of the pavement. It looks odd from the air, and I am looking forward to checking it out on the ground on our next flight. Be cautious if you encounter one of these in your flight planning. Wishing you all a COVID-free Spring and looking forward to seeing you at the coming Induction Ceremony at the EAA Museum. We’ll be notifying you all accordingly. And if you haven’t sent in your WAHF Membership Renewal, now is a good time to do so! On the cover: Marking the 75th Anniversary of the Pitts Special. This is Sammy Mason’s Pitts Special. t.d.eisele@att.net The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. Photo courtesy of EAA/Darin LaCrone (per Director of Communications). © 2020 EAA/Darin LaCrone

WEEDEN’S REVIEW Kelch Aviation Museum Partners with WAHF By Patrick Weeden I love my job, but folks, let me be frank: opening a new aviation museum in the upper Midwest is a daunting task, even under normal conditions. This region is chock-full of fine collections of vintage aircraft and memorabilia specialty and local history museums. And, in Wisconsin itself, the EAA Aviation Museum offers an incredible world-class collection practically in our backyard! Add to that, the countless smaller volunteerrun museums and organizations scattered around the state, and we’ve got a treasure trove of aviation history available to be cherished and visited often. This is not a competition, of course, since museums with a similar focus can all complement and enhance each other, instead of fighting for visitors and donations. Yet perhaps the most difficult challenge for a new institution is differentiating ourselves from the rest, with a story and a mission all our own. Attendance to museums and cultural institutions has been changing for years, thanks to the digital age and YouTube in our pockets for “on-demand” knowledge. Add to that, 2020’s global pandemic, and the future of small museums can seem as precarious as landing a Luscombe in a stiff crosswind! Excited to share a unique niche of aviation history – the Golden Age between the wars – we at the Kelch Museum took off, in spite of the challenges. Back when the Kelch Aviation Museum was formally organized in 2014, we created a plan to provide an educational function in the local community. The museum would focus on vintage aviation, yes, but we would also actively support STEM-based knowledge and education through classes and seminars. Engineering, science, and math drove the innovation that was key to the “Golden Age of Aviation” between 1920 and 1940, and, to this day, they keep our modern world moving. The meeting of old and new, the way history informs our present as well as our past, is a cornerstone of Kelch Aviation Museum. Our goal is be as inclusive as possible, and to open up the sometimes secretive world of aviation to a wide diverse audience. Being the new kids on the block, as it were, the museum leadership looked early on for supporters and organizations to legitimize our new venture. Articles in prominent magazines helped tremendously, as did significant donations from philanthropists and foundations, both near and far. Word began to spread by 2016, financial support for the new museum facility really took off in 2018 – and, in July 2020, we received perhaps one of the most significant affirmations a new museum could hope to get: The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. WAHF president Tom Thomas had contacted me earlier in the year to explore the possibility of partnering with Kelch to provide a home for all of the “stuff” that the Hall of Fame had collected over 30 years. The collection – photos, historical rec2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ords, artwork, membership rosters, and more – had lived in the basement of John and Rose Dorcey’s Oshkosh home, but the collection needed somewhere more secure. The brand-new Kelch museum building was the perfect place: Climatecontrolled, already home to our own archives, and just a short drive away from Oshkosh. Tom T. and Chris Campbell visited the museum hangar in July and agreed the space would make a perfect home for the “stuff.” So, I set out to make it happen. The Kelch Aviation Museum board of directors had already signaled that a partnership between the two organizations would be beneficial to both. A little more selfishly, having the confidence of Tom and the rest of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame leadership would be a nice big feather in the cap of a new aviation museum’s quest for legitimacy. We drafted a memorandum of understanding about how everything would be physically stored, who would have access from either organization, and a general timeline of when the “stuff” would be moved. (When Tom wasn’t paying attention, we made sure he was responsible for all the heavy lifting!) Now, to be clear, I have my fingers in both organizations and I want to be transparent about that. I am now proudly serving on the board of directors of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame, and of course, I am the Executive Director and ex-officio board member of the Kelch Aviation Museum. (Ex-officio is a fancy way of saying I get to speak, but not vote. In other words, they don’t have to listen to me.) Bringing the two together and creating a permanent “home base” for WAHF was never about me, nor will it ever be. It is about creating a mutually favorable arrangement regardless of who is running the show years from now. Arrangements were made. During the summer, several trucks and vans made the journey from Dorcey’s to Brodhead Airport. Boxes were photographed and numbered as they were loaded and unloaded, and everything was stacked neatly on pallets in the newly completed museum hangar for temporary safe-keeping.

WEEDEN’S REVIEW PHOTO SPECTRUM: Overview of the airport during a fly-in; a new building at Kelch Aviation Museum; and the “stuff” from WAHF Once the museum’s climate-controlled archive space is completed over the winter, most everything will be moved there for permanent storage. It will be separated from the extensive archive that the museum holds, yet all items will be part of our library inventory system that tracks the location and status of every item in the building. Best of all, the museum will dedicate space for a permanent display or exhibit for the Hall of Fame. The Kelch Aviation Museum is technically still closed to the public for the time being, and not only because of the pandemic. Our building project is divided into three phases, and we are just starting phase two in November. Phase one was our 12,000 sq. ft. main hangar, which was completed in March, 2020. But it is currently just an airplane hangar, so there is no public access until the rest of the facility is built. Once phase two is complete, planned for April, 2021, the display areas, restrooms, offices, and the aforementioned archive space, will allow us to open the doors. Plan on a springtime grand opening in 2021, COVID-19 notwithstanding. It is important to note that our entire museum project is expected to cost $1.4 Million by the time it is complete, and every dollar of that will have been donated. The museum is not borrowing any money. We have raised well over $1 Million to date, which is a testament to the broad support we enjoy from the local public and the aviation community around the world. This effort would simply not be possible without the backing of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame and the high regard in which you all are held. We will strive to live up to the high standards set by WAHF and the trust you have placed in us. After all, there’s no such thing as having too many aviation museums. Photos courtesy of Patrick Weeden Patrick Weeden is the Executive Director of the Kelch Aviation Museum at Brodhead Airport (C37), a Board member of the Brodhead Pietenpol Assn., and a Board member of WAHF. He is a private pilot and has been involved with vintage aircraft operation and restoration since childhood. 3 Forward in Flight – Winter 2020-2021

MEDICAL MATTERS Don’t Forget to Remember Blood Clots: DVTs and PEs By Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME Many activities in life have their own quirky sayings. For basketball, it may be, “You miss every shot you don’t take.” If you’ve ever played a pick-up game at the “Y,” you will see many players who strongly subscribe to this belief. For a barn-find collector car, it may be, “It ran the last time I drove it,” even though multiple families of mice have feasted on the wiring. In aviation: “How do you make a little money flying? Start with a lot.” In medical training, the mantra, “You miss every pulmonary embolism you don’t look for,” is repeatedly reinforced. A few years ago, my birthday fell on the day of a Packer game. As this was a “decade starting birthday,” we wanted to have a get-together with family and friends. We chose a local sports bar that would provide everyone a good view of the game and have enough room to move around. Family and friends often bounce medical questions off me. This was no different. In this case I was asked about a swollen leg. I recall the Packers were making a 4th quarter comeback and my distracted response was something to the effect of, “Yeah, that is not right, you should get that looked at,” when I noted that one of his legs was indeed larger than the other. The next day my friend called me and we discussed things a little more in depth. He did not recall any injury or new activity. It had been present for maybe a few days or a week or two at most ... hard to really pin down. It ached a little but was not really painful. He did not remember a bite or sting and had not noticed any redness to the skin. He did mention that he felt more tired than usual. Tiredness can mean a lot of different things to different people. In this case it was not “sleepy” tired. He had noted that he was more tired on his bike rides, barely able to go a mile or two, compared to his normal 20+ mile rides. The presence of leg-swelling and decreased exercise tolerance immediately makes two critical diagnoses jump off the chart ... a heart-related source; or a blood clot-related source. With the leg swelling in this case being one-sided, it pointed towards the Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE). These are large, blood-flow obstructing clots in the veins of the legs and lungs. While this case turned out to be pretty clear-cut, the diagnosis of a DVT or PE is not always this obvious. 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame The Basics Let’s go back to the basics. Plain and simple, our blood is an amazing collection of ingredients. In addition to carrying oxygen and nutrients, our blood also has the ability to make sure it stays where it is supposed to ... in the vessel ... even when the vessel is damaged. The blood needs to be able to remain liquid when in the vessel; but, at the same time, it must rapidly form a plug/clot when the vessel is damaged. Unfortunately, a system this complex has numerous steps where things can go awry. Problems in clotting or coagulation can generally be broken down into one of three categories, which are collectively known as Virchow’s Triad. Virchow’s Triad: -- Changes in blood flow -- Damage to the blood vessel -- Alterations to blood clotting chemicals In many patients with a clot, there is more than just one abnormality of Virchow’s Triad present. A 2006 study (Journal General Internal Medicine, 2006:21(7) 722) reviewed the charts of patients with confirmed blood clots (PE or DVT). This study found well over half of the patients with a confirmed clot had multiple risk factors present at the time of a clot. Conversely, only 10% of such patients had no identifiable risk factor The first of the triad listed above is changes in blood flow. This generally refers to decreased flow or stasis. Extended periods of immobilization can lead to clot formation, most commonly involving the legs. A leg being in a cast, or an excessive time spent seated, such as on an extended flight (generally considered over 4 hours), may meet this criterion. Another example may be extended immobilization while being hospitalized. This is why many hospitalized patients are started on preventive blood thinners when hospitalized or bed-ridden. The second category refers to damage or chemical changes to the blood vessel, generally the lining (also known as the endothelial surface of the vessel). Changes in the blood vessel may be noted during times of severe infection, or in the presence of chronic disease, such as hypertension or smoking. The third general category is alterations to the function of the blood itself. The physiology of blood and the coagulation cascade is one of the most challenging for any medical student;

MEDICAL MATTERS blood is not just red water. Numerous chemicals and proteins balance the forces of clotting and not-clotting. Some common medications (such as oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapies) carry increased risk. Other common medications, such as certain antidepressant medications, also alter the coagulation cascade. Another condition that carries significantly increased risk of clot formation is cancer. Malignancy throws the whole body into disarray and even alters clotting in areas unrelated to the actual site of the cancer. In some cases, the presence of a DVT or PE will trigger the search for an otherwise undiagnosed cancer. The other large component of this third category would be a genetic or acquired alteration to the clotting factors. Conditions such as Factor V leiden, antiphospholipid syndrome, protein C or S deficiency, would fall into this category. tailed family history of clotting disorders may be needed. If lab testing to evaluate for a clotting disorder was performed, those test results should be submitted as well. In some cases, an evaluation for a hidden cancer or malignancy is also indicated. For those treated with Warfarin, a minimum six-week monitoring period is required, plus at least six blood tests (INR) to confirm that therapeutic levels are achieved and stable. For those treated with an Eliquis- or Xarelto-type medication, a minimum two-week monitoring period is required. If the above information is reviewed and favorable, an AME Assisted Special Issuance (AASI) is generally granted by the FAA. An AASI is usually valid for three to five years and allows the AME to issue a certificate yearly and submit documentation to the FAA after the exam. This is different from a regular Special Issuance, where the FAA must review the documentation prior to issuance of the medical certificate. Treatment At future examinations, for the AME to issue, the pilot must Fortunately, treatment has progressed significantly over the past few years. For many years the mainstays of treatment were IV provide certain required documentation. This will generally inheparin and then starting oral warfarin. (Interesting side note -clude an updated status report from the treating provider, includWarfarin was developed by researchers at the University of ing the dose of any medication. If monitoring lab work is done, Wisconsin. Its name comes from the acronym WARF for this will also be included. The treating provider should specificalWisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.) Next came the development of low molecular weight hepa- ly comment on the lack of any side-effects, and also the lack of rin, such as Lovenox. This allowed for subcutaneous administra- any episodes of significant bleeding or new DVT/PE formation. If all documentation is present and the AME feels all criteria tion of medication, rather than the IV administration required of are met, a time-limited certificate will be issued with a limitation, heparin. This greatly improved patient comfort because it al“Not Valid For Any Class after MM/DD/YYYY”. This time lowed for outpatient treatment rather than hospitalization while limitation will generally expire the last day of the month twelve on the intravenous heparin. More recently came the development of direct oral antico- months in the future. If a new DVT/PE develops during this year, or prior to the agulants (DOAC). These are medications such as Xarelto, next exam, the airman would be expected to ground himself (14 Eliquis, and Pradaxa. These medications have been a gamechanger because they do not require the frequent blood draws CFR 61.53 Prohibition on Operations During a Medical Deficienand dose changes that coumadin requires. cy) FAA Medical Certification Now that we have a little background, this brings us to the topic of FAA medical certification in the presence or history of a DVT or PE. In most cases, a 3rd class applicant with a remote history of a single, isolated DVT/PE, and no current symptoms or need for treatment, will not have an issue being certified. However, 1st and 2nd class applicants, or those with multiple episodes and ongoing treatment, will need an FAA decision for certification. This determination cannot be made by the AME alone. As with every medical condition that requires an FAA decision, the airman will need to submit records, records, and more medical records. If hospitalization was required, the admission and discharge summary are good starting places. Any test reports (such as ultrasound or CT) should also be included. Depending on whether there was a clear explanation of the reason why the clot developed (provoked vs. unprovoked), a de- Closing Back to my friend at the birthday party. The day after the party and after our discussion, he was convinced he needed to see his doctor. He was diagnosed with an extensive DVT and Pulmonary Embolism and was admitted to the hospital. He now takes Eliquis and has been able to get back to biking 40 miles a day. The most important point of this column is to listen to your body. Not every case of swelling, shortness of breath, or chest pain, will be due to a clot. But, if you don’t consider a DVT/PE, you will certainly miss it. And missing a PE may cost a life. [Dr. Reid Sousek is an FAA-designated Senior Aviation Medical Examiner, who offers Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 Pilot Medical Exams; and an HIMS AME, for drug/alcohol exams. Dr. Sousek has offices near Oshkosh and Menasha.] 5 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2020-2021

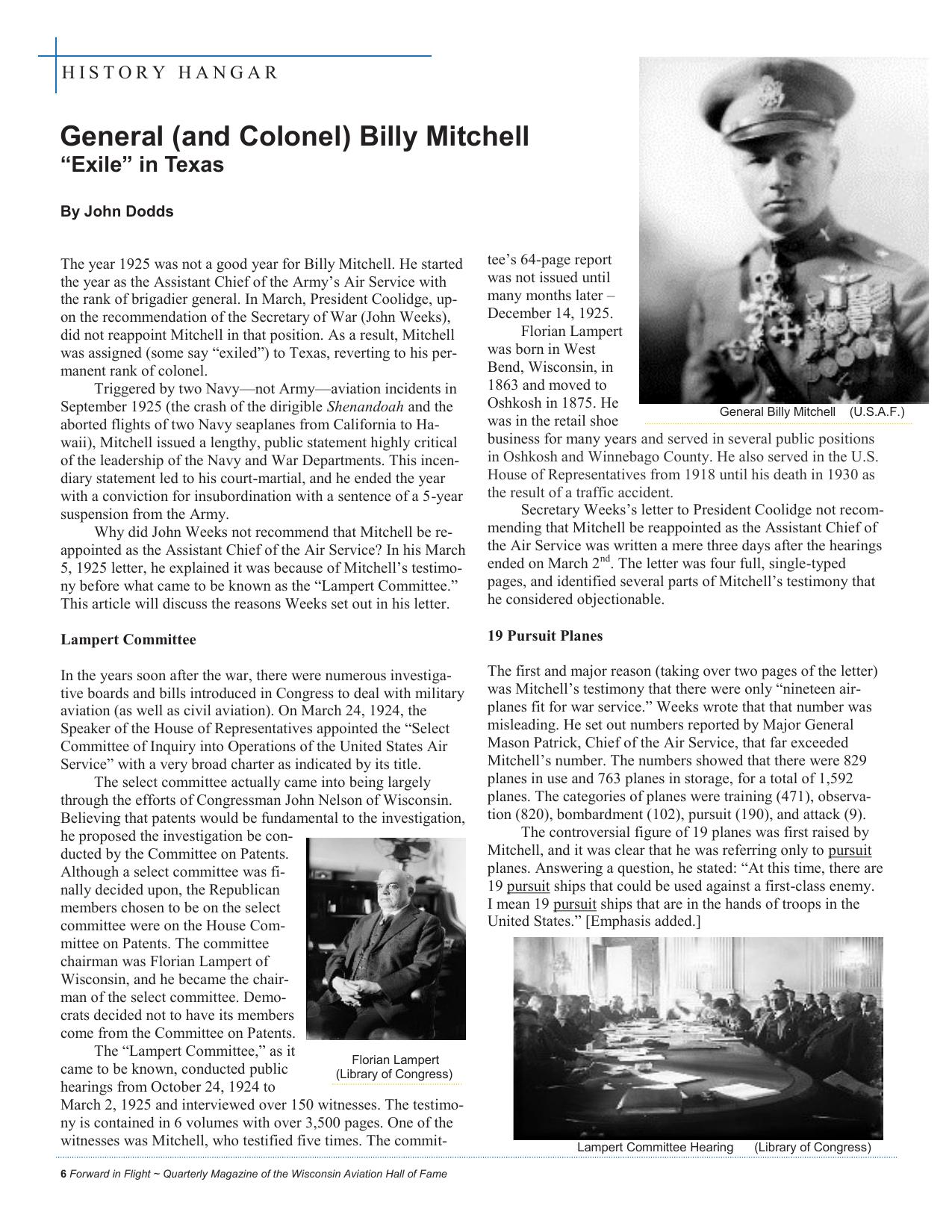

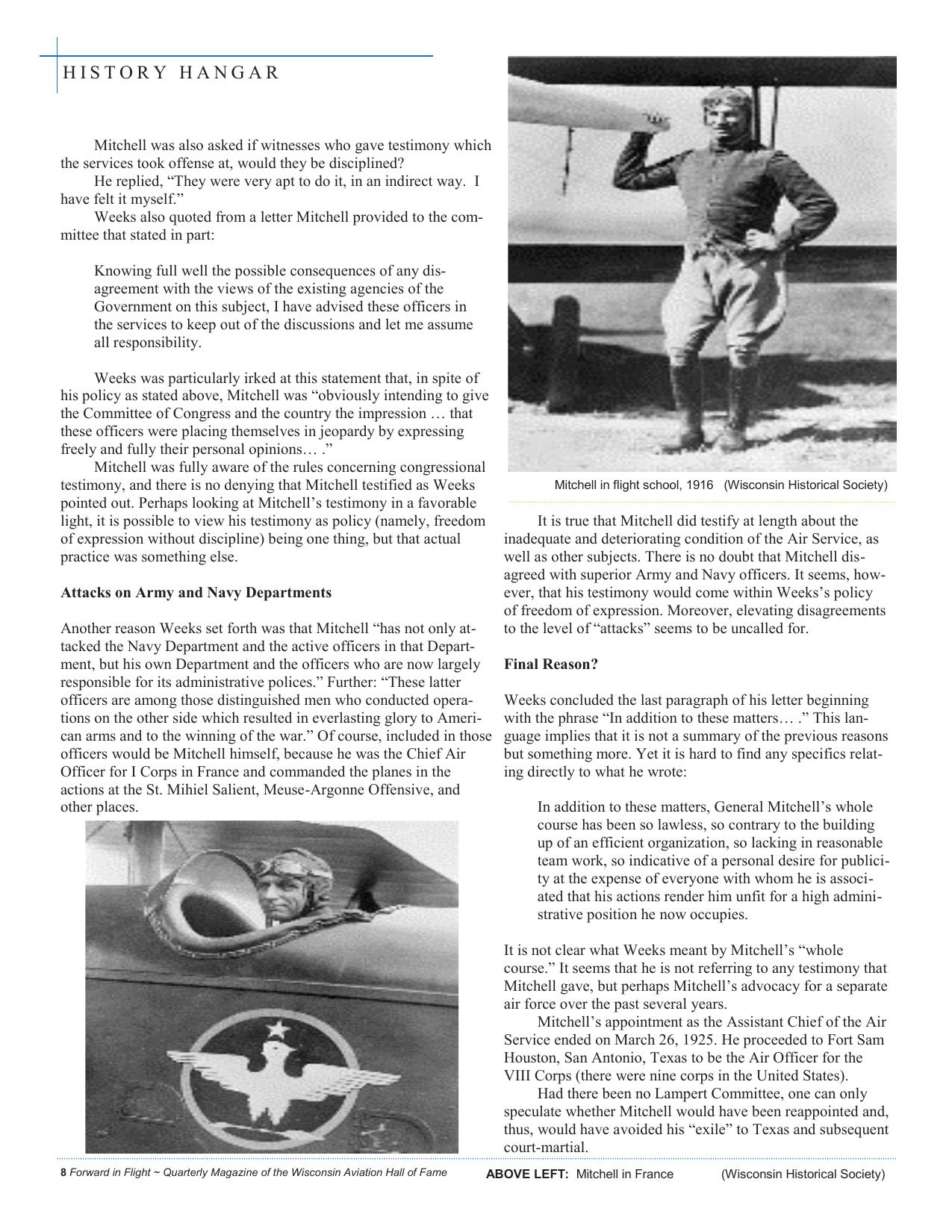

HISTORY HANGAR General (and Colonel) Billy Mitchell “Exile” in Texas By John Dodds The year 1925 was not a good year for Billy Mitchell. He started the year as the Assistant Chief of the Army’s Air Service with the rank of brigadier general. In March, President Coolidge, upon the recommendation of the Secretary of War (John Weeks), did not reappoint Mitchell in that position. As a result, Mitchell was assigned (some say “exiled”) to Texas, reverting to his permanent rank of colonel. Triggered by two Navy—not Army—aviation incidents in September 1925 (the crash of the dirigible Shenandoah and the aborted flights of two Navy seaplanes from California to Hawaii), Mitchell issued a lengthy, public statement highly critical of the leadership of the Navy and War Departments. This incendiary statement led to his court-martial, and he ended the year with a conviction for insubordination with a sentence of a 5-year suspension from the Army. Why did John Weeks not recommend that Mitchell be reappointed as the Assistant Chief of the Air Service? In his March 5, 1925 letter, he explained it was because of Mitchell’s testimony before what came to be known as the “Lampert Committee.” This article will discuss the reasons Weeks set out in his letter. tee’s 64-page report was not issued until many months later – December 14, 1925. Florian Lampert was born in West Bend, Wisconsin, in 1863 and moved to Oshkosh in 1875. He General Billy Mitchell (U.S.A.F.) was in the retail shoe business for many years and served in several public positions in Oshkosh and Winnebago County. He also served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1918 until his death in 1930 as the result of a traffic accident. Secretary Weeks’s letter to President Coolidge not recommending that Mitchell be reappointed as the Assistant Chief of the Air Service was written a mere three days after the hearings ended on March 2nd. The letter was four full, single-typed pages, and identified several parts of Mitchell’s testimony that he considered objectionable. Lampert Committee 19 Pursuit Planes In the years soon after the war, there were numerous investigative boards and bills introduced in Congress to deal with military aviation (as well as civil aviation). On March 24, 1924, the Speaker of the House of Representatives appointed the “Select Committee of Inquiry into Operations of the United States Air Service” with a very broad charter as indicated by its title. The select committee actually came into being largely through the efforts of Congressman John Nelson of Wisconsin. Believing that patents would be fundamental to the investigation, he proposed the investigation be conducted by the Committee on Patents. Although a select committee was finally decided upon, the Republican members chosen to be on the select committee were on the House Committee on Patents. The committee chairman was Florian Lampert of Wisconsin, and he became the chairman of the select committee. Democrats decided not to have its members come from the Committee on Patents. The “Lampert Committee,” as it Florian Lampert came to be known, conducted public (Library of Congress) hearings from October 24, 1924 to March 2, 1925 and interviewed over 150 witnesses. The testimony is contained in 6 volumes with over 3,500 pages. One of the witnesses was Mitchell, who testified five times. The commit- The first and major reason (taking over two pages of the letter) was Mitchell’s testimony that there were only “nineteen airplanes fit for war service.” Weeks wrote that that number was misleading. He set out numbers reported by Major General Mason Patrick, Chief of the Air Service, that far exceeded Mitchell’s number. The numbers showed that there were 829 planes in use and 763 planes in storage, for a total of 1,592 planes. The categories of planes were training (471), observation (820), bombardment (102), pursuit (190), and attack (9). The controversial figure of 19 planes was first raised by Mitchell, and it was clear that he was referring only to pursuit planes. Answering a question, he stated: “At this time, there are 19 pursuit ships that could be used against a first-class enemy. I mean 19 pursuit ships that are in the hands of troops in the United States.” [Emphasis added.] 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Lampert Committee Hearing (Library of Congress)

HISTORY HANGAR The committee was confused about the difference in the number of planes, but it was easily explained by information submitted by General Patrick, the Chief of the Air Service. Patrick had previously prepared a report on the number of airplanes. The report contained this cautionary note: “Particular attention is invited to the legend appearing at the foot of this tabulation which establishes the requirements in connection with the different aircraft as ‘first line,’ ‘second line,’ and ‘reserve.’” And the footnote legend described “first line” as “First service, would be ordered in a war emergency.” “Second line” was described as “would not be ordered in an emergency but compare reasonably well with foreign types. Fit for war use.” “Reserve” was described as “unfit for hard usage of war, fatally handicapped in relative performance, use for tactical training.” The number of first-line pursuit planes was 21, very close to the number cited by Mitchell. When Weeks testified, he was questioned whether he was acquainted with the three lines of airplanes. His response: “That division does not appeal to me. I prefer to talk about planes as in the classes in which they are given in that list – observation, training, bombardment, pursuit, and attack.” He was referring to Patrick’s report mentioned above. He was directly asked if he disputed that there were only 19 firstSecretary John Weeks line pursuit planes. Unbelievably, he responded: “I would like to have it made definite what a first line plane is.” It was then explained to him what the lines were. He was also asked that if the report (by Patrick) shows 21 planes, and since two were lost, would that not be 19 planes? He seemed to be clearly frustrated and responded: “That has not been clear from the standpoint of the country. The country thinks we only have 19 machines of any kind.” Weeks did not explain who “the country” was or why the country “thinks” that. Mitchell’s testimony clearly referred to “first-class pursuit planes” and Patrick’s report clearly revealed the different lines (first, second, and reserve). The hearing, in which it was clearly explained to Weeks the different lines of pursuit planes, was held on February 28, 1925. Undaunted, it was only five days later that Weeks sent his March 5th letter to President Coolidge. He concluded this subject by stating that when Mitchell testified as to the 19 pursuit planes, he “apparently endeavored to startle the country by testifying that only nineteen planes were fit for service, at the same time making no reasonable explanation of the number of planes on hand and their condition.” Curiously, Weeks did not inform President Coolidge that the matter of the 19 airplanes was clearly explained to him only several days before. Accordingly, it could be argued that Weeks misled President Coolidge when he did not lay out the full explanation about the 19 pursuit planes. ABOVE: TIME magazine archives Organization of the Air Service Secretary Weeks also wrote: “I think I ought to add that in my judgment the organization of the Air Service… is sound.” A major issue in the hearing was whether there should be an air force separate from the Army. Mitchell had testified repeatedly with great fervor that the Air Service should be removed from the Army and made a separate service and that all services should be under a Defense Department. But Weeks in his letter did not refer to any of Mitchell’s testimony on this subject. It is not clear why Weeks added this gratuitous statement in the letter since it is not stated to be an actual reason for not recommending Mitchell to continue in his position. “Muzzled” The second reason was explained by Weeks as follows: Furthermore, General Mitchell has given the country the impression that officers of the Army are muzzled and do not dare to express their views. “Muzzled” was a word that appeared in the press and was not used by Mitchell. Weeks pointed out that if any officer felt that way, then he was not informed of Army policy which he could have obtained “by making the slightest inquiry.” He then quoted the instructions on this subject that he had given, as well as those given by his predecessor, which he said were known to Mitchell. This policy concerned testifying before Congressional committees. His predecessor’s instructions made clear that “officers are free to testify as to their opinions and beliefs when summoned before appropriate” Congressional committees.” Weeks was just as clear: “In testifying before Congressional Committees, if their views are contrary to the views of the War Department, they will state to the committee that they are not speaking for the Department policy but are expressing their own personal views, and should do so without reservation.” The freedom to give opinions before congressional committees was an unanticipated subject that came up in Mitchell’s testimony. Mitchell’s testimony not only concerned committee members, but it also created a firestorm in the press. He explained that his term as Assistant Chief was up on March 26th and that, if he were not reappointed by the President, he would be assigned elsewhere. One Congressman surmised that his appointment “has probably gone through.” Mitchell said it had not, “so I imagine that it may not be made on the account of the evidence that I have given before the committees.” Weeks pointed out in his letter that Mitchell had testified that it would be impossible for the committee to obtain correct information from the services because of “fear of officers that if they testified, they would be subject to indirect disciplinary action by their departments.” Mitchell did so testify. He was asked this question: “How can a congressional committee get evidence from the various branches from the service unless someone comes and tells what he thinks?” Mitchell responded, “It cannot. It is impossible.” 7 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2020-2021

HISTORY HANGAR Mitchell was also asked if witnesses who gave testimony which the services took offense at, would they be disciplined? He replied, “They were very apt to do it, in an indirect way. I have felt it myself.” Weeks also quoted from a letter Mitchell provided to the committee that stated in part: Knowing full well the possible consequences of any disagreement with the views of the existing agencies of the Government on this subject, I have advised these officers in the services to keep out of the discussions and let me assume all responsibility. Weeks was particularly irked at this statement that, in spite of his policy as stated above, Mitchell was “obviously intending to give the Committee of Congress and the country the impression … that these officers were placing themselves in jeopardy by expressing freely and fully their personal opinions… .” Mitchell was fully aware of the rules concerning congressional Mitchell in flight school, 1916 (Wisconsin Historical Society) testimony, and there is no denying that Mitchell testified as Weeks pointed out. Perhaps looking at Mitchell’s testimony in a favorable light, it is possible to view his testimony as policy (namely, freedom It is true that Mitchell did testify at length about the of expression without discipline) being one thing, but that actual inadequate and deteriorating condition of the Air Service, as practice was something else. well as other subjects. There is no doubt that Mitchell disagreed with superior Army and Navy officers. It seems, however, that his testimony would come within Weeks’s policy Attacks on Army and Navy Departments of freedom of expression. Moreover, elevating disagreements Another reason Weeks set forth was that Mitchell “has not only atto the level of “attacks” seems to be uncalled for. tacked the Navy Department and the active officers in that Department, but his own Department and the officers who are now largely Final Reason? responsible for its administrative polices.” Further: “These latter officers are among those distinguished men who conducted operaWeeks concluded the last paragraph of his letter beginning tions on the other side which resulted in everlasting glory to Ameri- with the phrase “In addition to these matters… .” This lancan arms and to the winning of the war.” Of course, included in those guage implies that it is not a summary of the previous reasons officers would be Mitchell himself, because he was the Chief Air but something more. Yet it is hard to find any specifics relatOfficer for I Corps in France and commanded the planes in the ing directly to what he wrote: actions at the St. Mihiel Salient, Meuse-Argonne Offensive, and other places. In addition to these matters, General Mitchell’s whole course has been so lawless, so contrary to the building up of an efficient organization, so lacking in reasonable team work, so indicative of a personal desire for publicity at the expense of everyone with whom he is associated that his actions render him unfit for a high administrative position he now occupies. It is not clear what Weeks meant by Mitchell’s “whole course.” It seems that he is not referring to any testimony that Mitchell gave, but perhaps Mitchell’s advocacy for a separate air force over the past several years. Mitchell’s appointment as the Assistant Chief of the Air Service ended on March 26, 1925. He proceeded to Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas to be the Air Officer for the VIII Corps (there were nine corps in the United States). Had there been no Lampert Committee, one can only speculate whether Mitchell would have been reappointed and, thus, would have avoided his “exile” to Texas and subsequent court-martial. 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ABOVE LEFT: Mitchell in France (Wisconsin Historical Society)

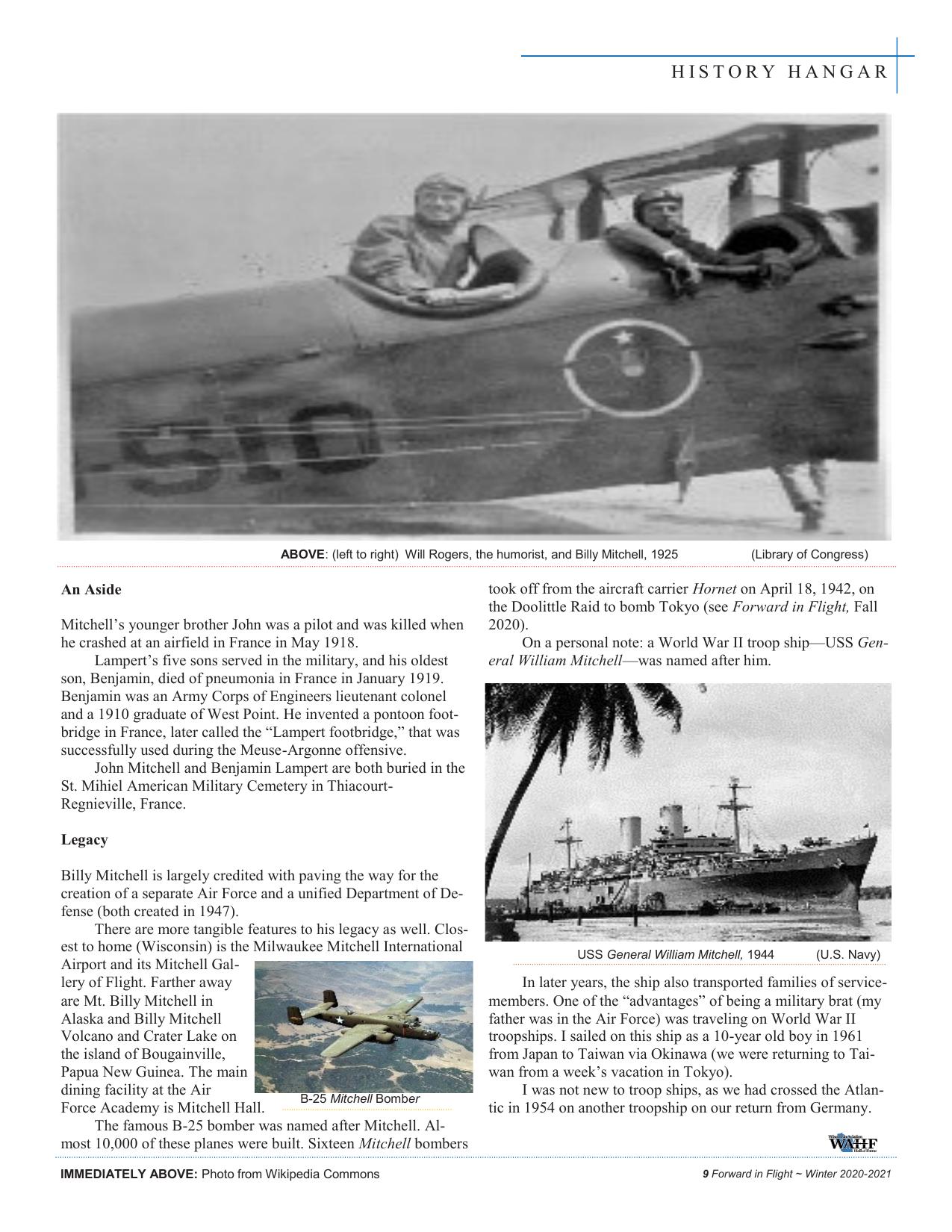

HISTORY HANGAR ABOVE: (left to right) Will Rogers, the humorist, and Billy Mitchell, 1925 An Aside Mitchell’s younger brother John was a pilot and was killed when he crashed at an airfield in France in May 1918. Lampert’s five sons served in the military, and his oldest son, Benjamin, died of pneumonia in France in January 1919. Benjamin was an Army Corps of Engineers lieutenant colonel and a 1910 graduate of West Point. He invented a pontoon footbridge in France, later called the “Lampert footbridge,” that was successfully used during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. John Mitchell and Benjamin Lampert are both buried in the St. Mihiel American Military Cemetery in ThiacourtRegnieville, France. (Library of Congress) took off from the aircraft carrier Hornet on April 18, 1942, on the Doolittle Raid to bomb Tokyo (see Forward in Flight, Fall 2020). On a personal note: a World War II troop ship—USS General William Mitchell—was named after him. Legacy Billy Mitchell is largely credited with paving the way for the creation of a separate Air Force and a unified Department of Defense (both created in 1947). There are more tangible features to his legacy as well. Closest to home (Wisconsin) is the Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport and its Mitchell Gallery of Flight. Farther away are Mt. Billy Mitchell in Alaska and Billy Mitchell Volcano and Crater Lake on the island of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea. The main dining facility at the Air B-25 Mitchell Bomber Force Academy is Mitchell Hall. The famous B-25 bomber was named after Mitchell. Almost 10,000 of these planes were built. Sixteen Mitchell bombers IMMEDIATELY ABOVE: Photo from Wikipedia Commons USS General William Mitchell, 1944 (U.S. Navy) In later years, the ship also transported families of servicemembers. One of the “advantages” of being a military brat (my father was in the Air Force) was traveling on World War II troopships. I sailed on this ship as a 10-year old boy in 1961 from Japan to Taiwan via Okinawa (we were returning to Taiwan from a week’s vacation in Tokyo). I was not new to troop ships, as we had crossed the Atlantic in 1954 on another troopship on our return from Germany. 9 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2020-2021

BOOK REVIEW “The Lost Pilots: The Spectacular Rise and Scandalous Fall of Aviation’s Golden Couple” Murder or Suicide? By John Dodds Displayed on a shelf at my local library, this book’s intriguing cover and title caught my eye. After a quick glance at the inside cover, I decided to check out the book. I was not disappointed; in fact, it is a fascinating book. “Aviation’s Golden Couple” referred to in the subtitle are Bill Lancaster, an English aviator who flew in World War I, and Jessie “Chubbie” Miller, a young woman from Australia. Flying from England to Australia in 1927-1928 in a two-seater bi-plane certainly gave them their well-deserved fame for a while. While I am not convinced that they were aviation’s golden couple, I am convinced that they were a couple (although not married) in the Golden Age of Aviation. Or should I say Golden Age of Flight? The Air & Space Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., has an exhibit titled “Golden Age of Flight” described on its website as follows: Americans were wild about aviation in the 1920s and '30s, the period between the two world wars that came to be known as the Golden Age of Flight. Air races and daring record-setting flights dominated the news. Airplanes evolved from wood-and-fabric biplanes to streamlined metal monoplanes. The military services embraced air power. Aviation came of age. Notably, the main plane featured in the exhibit is the Wittman Buster that hangs near the entrance to the exhibit. This airplane began life in 1931 as Chief Oshkosh and was modified over the years. Following a crash in 1938 and long-term storage, it was rebuilt and re-emerged as Buster in 1947. Steve Wittman was inducted into the WAHF in 1986. ABOVE: Wittman Buster (Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum) 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame The opening scene of the book is a party (more about this party later) in London in June 1927 where Chubbie meets Bill. She learns of his plan to fly solo from England to Australia, a “record-setting flight” for a light aircraft. Over the next couple weeks, she convinces him to take her along (she was not a pilot). Both are married, although unhappily. After several months of preparation, they left England in mid-October. The plane was named Red Rose, which was Bill’s mother’s nickname in the flower club to which she belonged. Left unsaid in the book, it seems clear that her nickname was derived from her last name of Lancaster. In England’s War of the Roses in the 1400s, the symbol of the House of Lancaster was the red rose and that of the House of York the white rose. The same is true today in Pennsylvania, for example, for the cities of Lancaster (red rose) and York (white rose). The plane they flew was an Avro Avian. Avro also made the famous World War II bomber, the Avro Lancaster. Later, Avro made the nuclear-capable Vulcan bomber that was featured in the 1965 James Bond movie Thunderball (my favorite 007 movie). The book describes the route they flew, so it is easy to follow along as you read. I did come to a jarring halt, however, when the book states that they flew from Tripoli to Benghazi via Homs, Syria. Syria? The distance from Tripoli to Benghazi is about 425 miles, and it is 2,240 miles if you detour to Homs, Syria. With a quick trip to Libya via Google Earth, I discovered that the real destination was Khoms, a town in Libya between Tripoli and Benghazi. I contacted the author who acknowledged the error. [book review continued at page 22] BOOK COVER: All rights reserved by the author, Corey Mead, and the publisher, Macmillan (Flatiron Books, 2018).

SHORT STORY A Path in the Air For Bill, who loved to fly By Dean Zakos 1945 was a good year. It was autumn, but the leaves were still weeks away from curling brown and crisp. The war had ended. High school graduation was last June. I planned to enlist in the Navy after two years of college. I wanted to be a Naval Aviator. The Navy had a program so I could enlist, go to college for two years, fly for the Navy, and then complete the second two years of my education and get my degree. I wanted to be an engineer. I glued kites and model airplanes out of balsa wood and tissue paper as soon as I could safely handle a scissors and pocketknife at about five or six years of age. I learned to fly a Piper J3 Cub in the summer of 1944. Cappy, my flight instructor, said I had the makings of a good pilot. I hoped so. I had not flown for a few weeks – money and time were always tight. I finished early at my part-time job at the hardware store. Some daylight still remained. The shadows were growing longer and the light softer as I cuffed my faded corduroy trousers and pointed my bike toward the airport. Late September’s sights, smells, and sounds greeted me everywhere. A freshly mown lawn. Victory gardens. The Fitzgeralds, with all nine kids, talking and laughing, on their front porch. Doris Day singing “Sentimental Journey” on a radio somewhere. Railroad men, lunch buckets swinging from their grease-stained hands, walking home from the rail yard. Bells chiming in the steeple of St. Mary’s. The aromas of suppers being prepared on kitchen stoves. The ding-ding as a ’37 Ford coupe pulled into the Clark gas station on the corner. As I followed the road away from the edge of town, I peered out over rolling acres of soonto-be-harvested corn, standing high in straight rows with tassels swaying in unison in the mild breeze. I took in the pungent odor of dairy cows and manure. A redwing blackbird sat alone on a fence post. I travelled that country road many times over the years. I started washing airplanes and doing odd jobs around the airport when I was twelve in hopes of getting rides and, eventually, when I was old enough, some lessons. Even then, airplanes had a lot of surface area to pay attention to. I was always sure to be careful with the cotton/linen and dope fabric coverings, particularly the taped seams. A few Pipers and Taylorcraft, a Stinson, a Luscombe. There was even a Pheasant H-10 on the field. I washed them all. Arriving at the old shed serving as a hangar, I leaned my bike against the wall. I muscled apart the two halves of the door, suspended by wheels in a dented and weather-beaten overhead track, until both sides reached their stops. Within, it smelled of old wood, gasoline, and musty earth. The Cub, painted in Lockhaven yellow with a black lightning bolt stripe, sat still and ready on the hard-packed dirt floor. The 35 foot wing barely fit the space. At 18, I could lift the tail off the © Dean Zakos 2020. All rights reserved ground and pull the Cub out of the hangar by myself. Once I was satisfied that the machine would fly, I was ready to start up. Reaching in, I cracked the throttle and pushed the fuel lever to “On.” Today, there are not many pilots who will hand prop an airplane. When I started out, every pilot did. I reached back in and gave the engine two shots from the primer. I walked around to the nose and pulled the wooden propeller through three or four times. Set the blades to the ten o’clock and four o’clock positions. Back at the door, I reached over and above the rear seat, turning the magneto switch to “Both.” Standing next to the cowl, in front of the chocked tire, I placed my right hand on the prop and left hand on the tubular frame at the edge of the door. Steadied my feet. Gave it a spin. If done right, it is that simple. Started right up. Kicked the chock out. Settled into the rear seat and belted in. That day in late September, my life was in front of me. My personal horizon was as wide as the view out of the Cub’s windshield at a couple thousand feet. I did not know where fate would take me, but I knew I would be going by air. Back then, I was full of hope and aspirations. I did not have a special girl, but I thought I would eventually meet someone. And I did. At Pensacola. Barbara was a Southerner – her family was from Kentucky. I fell first for her expressive eyes, kind ways, and wonderful drawl. Then, I fell in love with her. We were married in her parents’ backyard under a painted gazebo covered in colorful spring flowers. Barbara in her wedding dress and me in my khaki Ensign uniform. The panel in the Piper was spartan. Airspeed, altimeter, oil pressure, oil temperature. A whiskey compass. In a Cub, everything happens at 60 miles an hour. I taxied out, lined up in the center of the turf runway, held the stick back in the fingers of my right hand, and wrapped my left palm around the black ball at the end of the throttle lever. Confirming there was nothing in front of me, I gently pushed the throttle forward to the stop. I did not need to look at the tachometer. I knew how much power was being made by the sound and vibration of the little four cylinder engine. Looking over the empty front seat, I confirmed that oil temp and pressure were normal. The wheels rolled forward, slowly at first. I pressed on the right rudder pedal. As speed increased and the tail came up, I moved the stick to neutral. I kept pressure on the right rudder pedal as needed to maintain directional control. Flying speed. Stick slightly back, the Cub flew itself into the air. 11 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2020-2021

SHORT STORY If you fly, you know the feeling. I experienced it on my first solo in the Cub and I know it still today so many, many years, and logged hours, later. The anticipation. The exhilaration. The concentration. The satisfaction. We are the lucky few. Climbing gracefully through clouds and sky, watching the earth fall away, we can make the horizon tilt and rise and fall and bend to our will. For me, I first saw flying as practical and, perhaps, a way out of a small town. In time, and with Barbara’s influence, I came to see flying as having more of a connection with poetry, a subject she knew well. Unlike poets, pilots do not write with words on a page. Instead, we write with airplanes on the vast and open expanse of the sky. The sky is a blank sheet, and what we can scribe there depends solely on our skills and experience and dreams. I banked the Cub south toward the river. When I was at about 500 feet above the ground, I nudged the throttle back and leveled off. The lower half of the Cub’s door was down, and the upper window half was up. If you cannot fly in an open cockpit airplane, the next best thing is to fly in an airplane with a window open or the canopy slid back, inviting the rattling slipstream in to swirl and buffet around you. At that altitude, the sights and smells of the world below are still clear and sharp. The sound and vibration of the engine were rhythmic and steady. Scattered clouds above me reflected the sun’s rays as it journeyed to meet the horizon. Pewter-white, edged in violets, silvers, and golds, the clouds reflected the angles of the end-of-day light in the melting blue of the sky. At that moment, it seemed as if my airplane was the only one in the world. There is a road coming up. Its direction perpendicular to my flight path. As I crossed, I turned the Cub to the left, holding a steady bank and noting the wind drift. As I crossed the road again, I banked to the right. After a few more S-turns, perfecting my track with each pass, I proceeded on my original course to the river. Few things teach you more about coordinated flight, wind, and wind drift than S-turns. I flew Corsairs and Avengers for the Navy. Too late for World War II and too early for Korea. Carrier qualified on both. I liked the Corsair for the speed, the Avenger for the room. I was stationed in Virginia with an anti-submarine squadron. I could fly the Avenger home on some weekends. Often, I would take a couple 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame of enlisted men with Wisconsin connections along with me. So long as we were back on the naval air station by 0800 Monday, there was no problem. The Navy wanted us to fly. Reaching the river, I inched the throttle back and started a gentle descent until the bald eagles, sitting patiently on tree limbs along the sandy banks, came clearly into view. I maneuvered the Cub as the river meandered, parallel with its line. First right, then left, then straight, then right again. There is a freedom and meaning in flight that most people could never hope to find on the ground. I am one with the Cub. I think “go right” and my little ship responds immediately. Hands and feet and ailerons and rudder move together - deliberately and responsively – exactly in accordance with my desires. Following the river’s contours, I lose myself in the moment. I am where I want to be. Eventually, the wire and cork fuel gauge bobbing on the cowl helps me to regain my focus. The mark showed about one-quarter full. It was getting late. Time to steer the Cub back toward the airport. Only about four miles away to the northwest. Still enough daylight to see the fields and county roads below and the few hangars and turf runway beyond. I will be there soon. I owned two Cessna Skyhawks (one a straight tail) over the years. Good, practical airplanes. I built an RV-7 with a tail wheel and flew it for many years. I have always liked the challenge of designing and building things. There is something special about using your ingenuity and your two hands to create some object that is useful and of value. Barbara and I flew the Skyhawks and the RV-7 as often as we could. Trips to North Carolina, Kentucky, Florida, and Texas. Even to Alaska – twice. Flew into Oshkosh and camped for the week almost every year. We had a good life. Did all my plans and dreams come true? No. But I have no real complaints either. I have always told my children not to wait for things to get easier, or simpler, or better. Life will always have disappointments and complications. Learn to be happy now. Otherwise, you will run out of time. If you have family and friends, and you can laugh and enjoy life – and fly airplanes – you are blessed. All images courtesy of Dean Zakos

SHORT STORY Barbara is gone now. She passed four years ago. I miss her every day. To help fill the emptiness, I sold the RV-7 and started to build a Zenith 701. It looks like it will be a fun airplane to fly. I have a small barn and workshop on my property. The work is slow going, but I have the time. Wings, tail, and fuselage are mostly complete. Engine is in a crate in the corner. Working on the panel layout. Entering the pattern on a left downwind to land to the west, I slide the throttle back. Slight crab angle to the south to compensate for a little drift. I swap the stick to my left hand as I reach forward with my right toward the front right side of the fuselage to pull the carb heat on, being careful not to push inadvertently on the stick as I stretch. I throttle back again as I turn base and final. I am on airspeed and altitude, nose held slightly low, with the grass strip growing larger in front of me. Crabbing a little to my left. Over the threshold, I close the throttle, lower the left wing a bit, raise the nose slightly, and hold it. Work the rudder pedals to center the nose on the middle of the runway. Hold it. No hurry. Hold it. Stick all the way back. Work the pedals. Hold it. The Cub settles gently, quietly, firmly. First the left wheel, then the right. I am down. Stick back in my stomach and to the left. Keep bumping the rudder pedals to stay straight. I remind myself, as Cappy told me, to continue to fly the airplane. On the ground, I slowly weave the nose of the Cub back and forth to allow some forward visibility until I am shut down in front of the hangar. I position the tail of the Cub toward the opening. Lifting at the hand hold, I pull backward, trudging carefully so as not to catch a wingtip on the door frame, until the cowl and prop pass under the door track and the main wheels settle into their indentations in the floor. After chocking a wheel, I pause for a moment in front of the open doors, slightly more darkness inside the hangar than out, listening to the crickets in the nearby meadow, the metallic ticking of the engine, and feeling the lingering warmth of the 65 horsepower Continental. I add some gas from a five gallon can to the Cub’s tank, wipe her All images courtesy of Dean Zakos down, and remove the few bugs that found their demise on the windshield or leading edges. The flight was at an end. I could hardly wait to do it all again. Heading back toward my little town that night in 1945, I could feel the chill in the air through my thin flannel shirt, reminding me that long, warm summer days were almost at an end. I was content. I did not know then where my flying, and my life, would take me. I did know flying gave me a sense of confidence and accomplishment that would serve me well. The moon, pale and orange, was rising in the east. The dark blue sky of twilight was fading into the deep black velvet of night. The quiet of evening was settling in. Streetlights began to flicker on as I continued toward home. Muted, golden glows appeared in windows and open doorways of the houses I passed, casting intricate patterns of lights and shadows on the lawns and trees. I was almost to my street. As I pedaled, I looked forward to bounding up our back porch, opening the screen door of our kitchen, and stepping into the warmth and comfort I knew I would find there. Ma said she was making meatloaf tonight. [Dean Zakos learned to fly at Batten Field in Racine (KRAC) and at the Westosha airport in Westosha (5K6). Dean was born in Fond du Lac, and currently lives in Madison. He is a member of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), the EAA, and several local chapters of the EAA. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin—Madison, and he has a law degree from Marquette University Law School. His recent book, Laughing with the Wind: Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot (Square Peg Books, 2019), is available at Amazon and at Barnes & Noble.] 13 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2020-2021

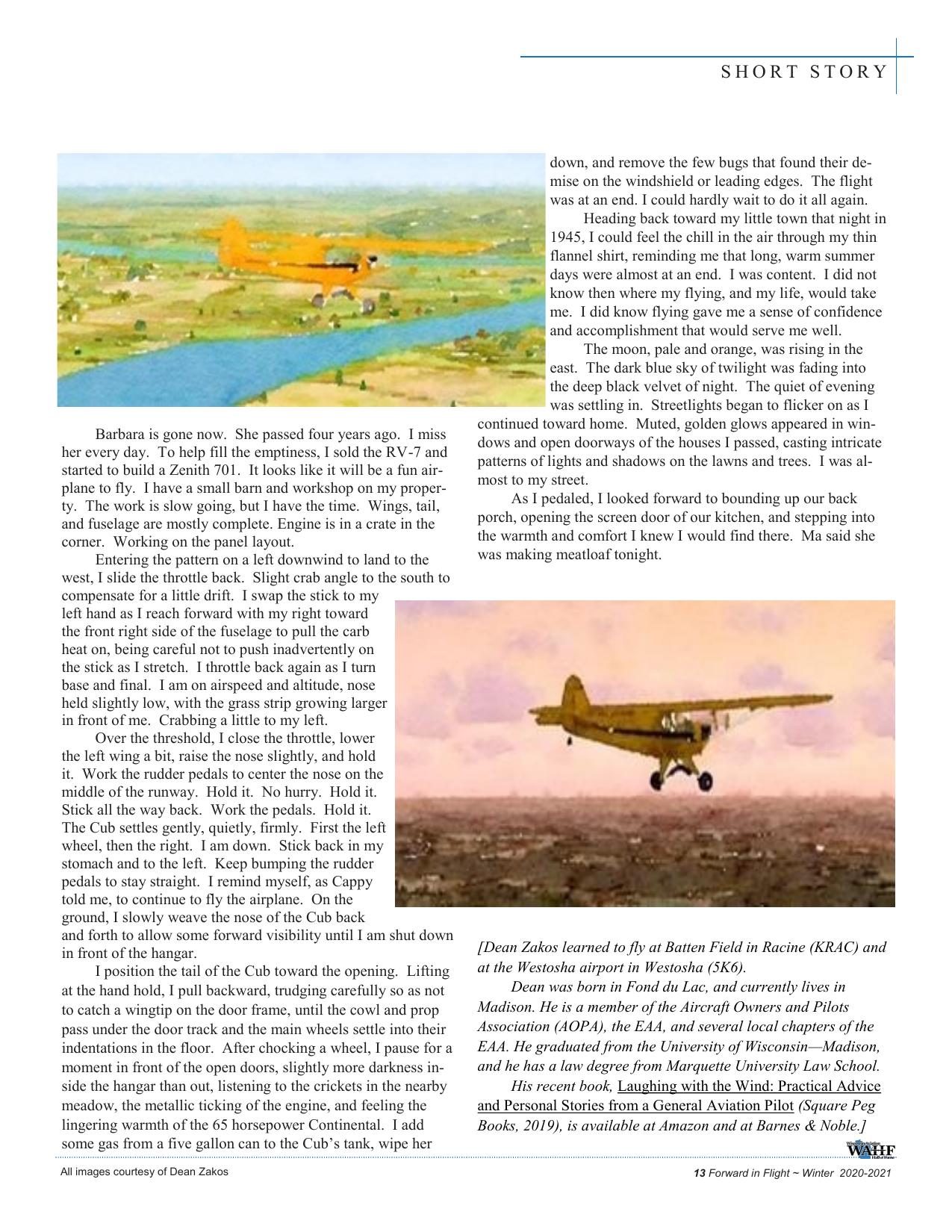

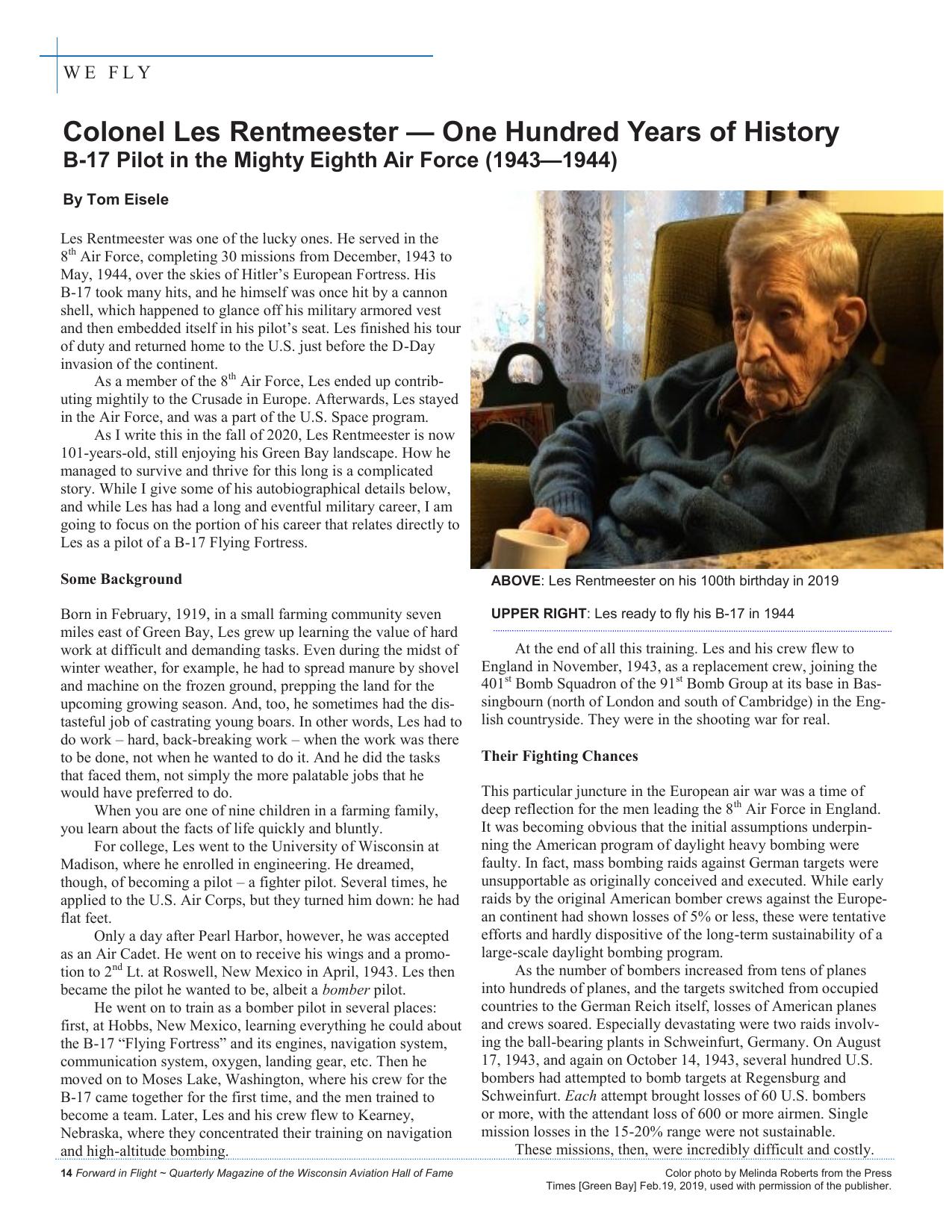

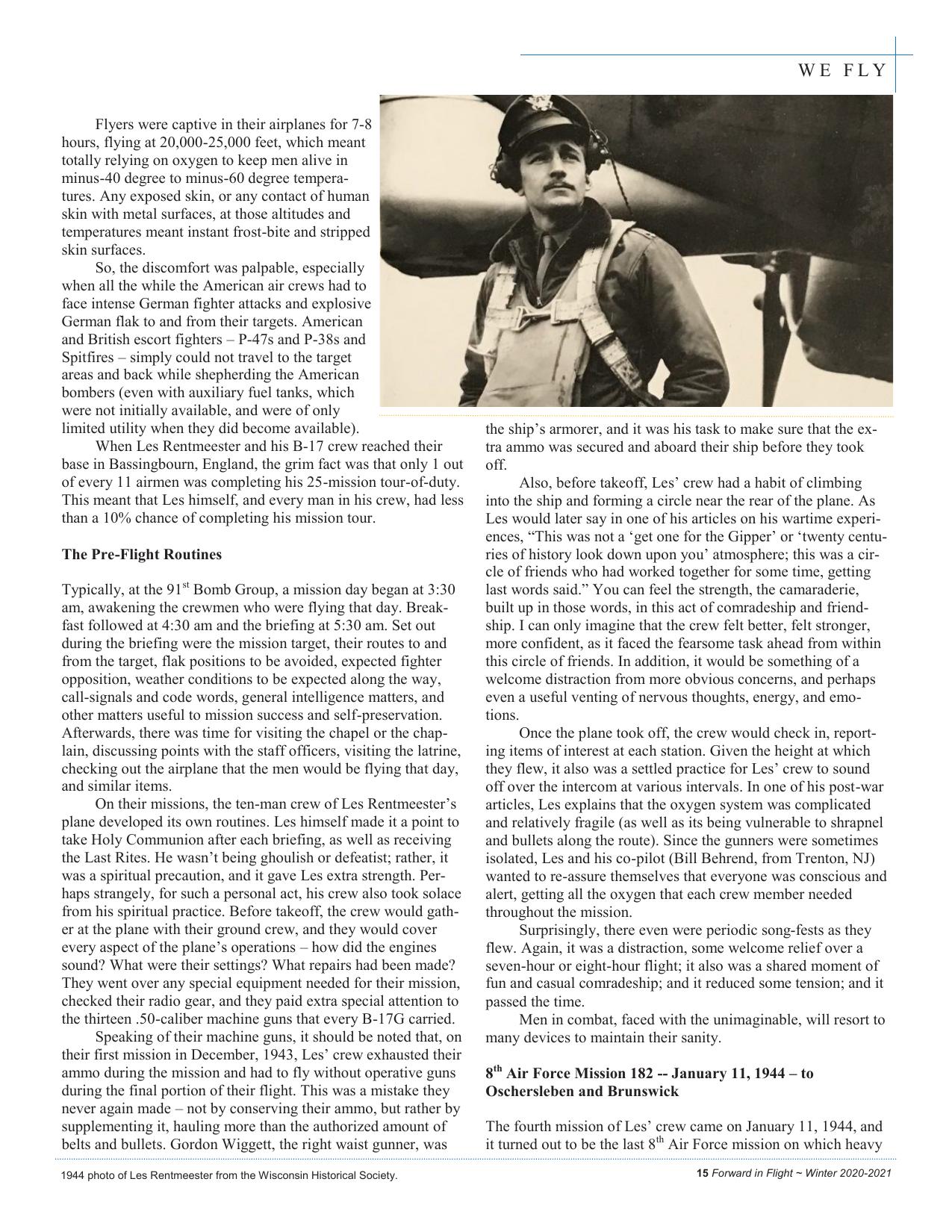

WE FLY Colonel Les Rentmeester — One Hundred Years of History B-17 Pilot in the Mighty Eighth Air Force (1943—1944) By Tom Eisele Les Rentmeester was one of the lucky ones. He served in the 8th Air Force, completing 30 missions from December, 1943 to May, 1944, over the skies of Hitler’s European Fortress. His B-17 took many hits, and he himself was once hit by a cannon shell, which happened to glance off his military armored vest and then embedded itself in his pilot’s seat. Les finished his tour of duty and returned home to the U.S. just before the D-Day invasion of the continent. As a member of the 8th Air Force, Les ended up contributing mightily to the Crusade in Europe. Afterwards, Les stayed in the Air Force, and was a part of the U.S. Space program. As I write this in the fall of 2020, Les Rentmeester is now 101-years-old, still enjoying his Green Bay landscape. How he managed to survive and thrive for this long is a complicated story. While I give some of his autobiographical details below, and while Les has had a long and eventful military career, I am going to focus on the portion of his career that relates directly to Les as a pilot of a B-17 Flying Fortress. Some Background ABOVE: Les Rentmeester on his 100th birthday in 2019 Born in February, 1919, in a small farming community seven miles east of Green Bay, Les grew up learning the value of hard work at difficult and demanding tasks. Even during the midst of winter weather, for example, he had to spread manure by shovel and machine on the frozen ground, prepping the land for the upcoming growing season. And, too, he sometimes had the distasteful job of castrating young boars. In other words, Les had to do work – hard, back-breaking work – when the work was there to be done, not when he wanted to do it. And he did the tasks that faced them, not simply the more palatable jobs that he would have preferred to do. When you are one of nine children in a farming family, you learn about the facts of life quickly and bluntly. For college, Les went to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he enrolled in engineering. He dreamed, though, of becoming a pilot – a fighter pilot. Several times, he applied to the U.S. Air Corps, but they turned him down: he had flat feet. Only a day after Pearl Harbor, however, he was accepted as an Air Cadet. He went on to receive his wings and a promotion to 2nd Lt. at Roswell, New Mexico in April, 1943. Les then became the pilot he wanted to be, albeit a bomber pilot. He went on to train as a bomber pilot in several places: first, at Hobbs, New Mexico, learning everything he could about the B-17 “Flying Fortress” and its engines, navigation system, communication system, oxygen, landing gear, etc. Then he moved on to Moses Lake, Washington, where his crew for the B-17 came together for the first time, and the men trained to become a team. Later, Les and his crew flew to Kearney, Nebraska, where they concentrated their training on navigation and high-altitude bombing. UPPER RIGHT: Les ready to fly his B-17 in 1944 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame At the end of all this training. Les and his crew flew to England in November, 1943, as a replacement crew, joining the 401st Bomb Squadron of the 91st Bomb Group at its base in Bassingbourn (north of London and south of Cambridge) in the English countryside. They were in the shooting war for real. Their Fighting Chances This particular juncture in the European air war was a time of deep reflection for the men leading the 8th Air Force in England. It was becoming obvious that the initial assumptions underpinning the American program of daylight heavy bombing were faulty. In fact, mass bombing raids against German targets were unsupportable as originally conceived and executed. While early raids by the original American bomber crews against the European continent had shown losses of 5% or less, these were tentative efforts and hardly dispositive of the long-term sustainability of a large-scale daylight bombing program. As the number of bombers increased from tens of planes into hundreds of planes, and the targets switched from occupied countries to the German Reich itself, losses of American planes and crews soared. Especially devastating were two raids involving the ball-bearing plants in Schweinfurt, Germany. On August 17, 1943, and again on October 14, 1943, several hundred U.S. bombers had attempted to bomb targets at Regensburg and Schweinfurt. Each attempt brought losses of 60 U.S. bombers or more, with the attendant loss of 600 or more airmen. Single mission losses in the 15-20% range were not sustainable. These missions, then, were incredibly difficult and costly. Color photo by Melinda Roberts from the Press Times [Green Bay] Feb.19, 2019, used with permission of the publisher.

WE FLY Flyers were captive in their airplanes for 7-8 hours, flying at 20,000-25,000 feet, which meant totally relying on oxygen to keep men alive in minus-40 degree to minus-60 degree temperatures. Any exposed skin, or any contact of human skin with metal surfaces, at those altitudes and temperatures meant instant frost-bite and stripped skin surfaces. So, the discomfort was palpable, especially when all the while the American air crews had to face intense German fighter attacks and explosive German flak to and from their targets. American and British escort fighters – P-47s and P-38s and Spitfires – simply could not travel to the target areas and back while shepherding the American bombers (even with auxiliary fuel tanks, which were not initially available, and were of only limited utility when they did become available). When Les Rentmeester and his B-17 crew reached their base in Bassingbourn, England, the grim fact was that only 1 out of every 11 airmen was completing his 25-mission tour-of-duty. This meant that Les himself, and every man in his crew, had less than a 10% chance of completing his mission tour. The Pre-Flight Routines Typically, at the 91st Bomb Group, a mission day began at 3:30 am, awakening the crewmen who were flying that day. Breakfast followed at 4:30 am and the briefing at 5:30 am. Set out during the briefing were the mission target, their routes to and from the target, flak positions to be avoided, expected fighter opposition, weather conditions to be expected along the way, call-signals and code words, general intelligence matters, and other matters useful to mission success and self-preservation. Afterwards, there was time for visiting the chapel or the chaplain, discussing points with the staff officers, visiting the latrine, checking out the airplane that the men would be flying that day, and similar items. On their missions, the ten-man crew of Les Rentmeester’s plane developed its own routines. Les himself made it a point to take Holy Communion after each briefing, as well as receiving the Last Rites. He wasn’t being ghoulish or defeatist; rather, it was a spiritual precaution, and it gave Les extra strength. Perhaps strangely, for such a personal act, his crew also took solace from his spiritual practice. Before takeoff, the crew would gather at the plane with their ground crew, and they would cover every aspect of the plane’s operations – how did the engines sound? What were their settings? What repairs had been made? They went over any special equipment needed for their mission, checked their radio gear, and they paid extra special attention to the thirteen .50-caliber machine guns that every B-17G carried. Speaking of their machine guns, it should be noted that, on their first mission in December, 1943, Les’ crew exhausted their ammo during the mission and had to fly without operative guns during the final portion of their flight. This was a mistake they never again made – not by conserving their ammo, but rather by supplementing it, hauling more than the authorized amount of belts and bullets. Gordon Wiggett, the right waist gunner, was 1944 photo of Les Rentmeester from the Wisconsin Historical Society. the ship’s armorer, and it was his task to make sure that the extra ammo was secured and aboard their ship before they took off. Also, before takeoff, Les’ crew had a habit of climbing into the ship and forming a circle near the rear of the plane. As Les would later say in one of his articles on his wartime experiences, “This was not a ‘get one for the Gipper’ or ‘twenty centuries of history look down upon you’ atmosphere; this was a circle of friends who had worked together for some time, getting last words said.” You can feel the strength, the camaraderie, built up in those words, in this act of comradeship and friendship. I can only imagine that the crew felt better, felt stronger, more confident, as it faced the fearsome task ahead from within this circle of friends. In addition, it would be something of a welcome distraction from more obvious concerns, and perhaps even a useful venting of nervous thoughts, energy, and emotions. Once the plane took off, the crew would check in, reporting items of interest at each station. Given the height at which they flew, it also was a settled practice for Les’ crew to sound off over the intercom at various intervals. In one of his post-war articles, Les explains that the oxygen system was complicated and relatively fragile (as well as its being vulnerable to shrapnel and bullets along the route). Since the gunners were sometimes isolated, Les and his co-pilot (Bill Behrend, from Trenton, NJ) wanted to re-assure themselves that everyone was conscious and alert, getting all the oxygen that each crew member needed throughout the mission. Surprisingly, there even were periodic song-fests as they flew. Again, it was a distraction, some welcome relief over a seven-hour or eight-hour flight; it also was a shared moment of fun and casual comradeship; and it reduced some tension; and it passed the time. Men in combat, faced with the unimaginable, will resort to many devices to maintain their sanity. 8th Air Force Mission 182 -- January 11, 1944 – to Oschersleben and Brunswick The fourth mission of Les’ crew came on January 11, 1944, and it turned out to be the last 8th Air Force mission on which heavy 15 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2020-2021

WE FLY bombers heading to German targets were not escorted all the way to their target. After this date, the 8th Air Force was able to provide escorting fighter cover to and from the targets – this huge improvement in bomber protection was partly due to added external fuel tanks and partly due to the introduction of the P-51B Mustang fighter as a full-time available escort. But, on January 11th in 1944, the 8th Air force did not have full-course or full-route escort protection for their bombers. Instead, as always, it would be a matter of the bombers maintaining their formation integrity, keeping their box formations as tight as possible, and presenting as few as possible vulnerabilities or holes to the German defending fighters. And, of course, the German flak simply had to be suffered; there was no way to avoid running the flak gauntlet around the targets. The bombers certainly avoided or dodged known flak concentrations whenever they could, on their way to and from the targets, but at some point on their bomb runs, they had to maintain their formation positions and take their chances with the anti-aircraft fire coming up at them. On this Mission 182 for the 8th Air Force, it was a group comprising more than 660 bombers from all three Air Divisions, and they were heading for three distinct targets in Germany, all of the targets relating to the German aviation industry in some way or another. The 8th AF wanted to put the Luftwaffe out of action permanently. Les’ B-17 was in the group headed toward the Focke-Wulf plants in Oschersleben, and their plane was in a formation of 6-planes forming the low squadron for the 91 st Bomb Group within their wing of bombers. The cloud cover in England caused delays in takeoffs and forming up, and some of the heavy bombers were recalled by General Jimmy Doolittle, now the commanding officer of the 8th Air Force. Les’ group was not recalled, however, so they pressed on, gradually reaching their bombing altitude of 24,000-ft. as they crossed the English Channel and entered European air space. As they crossed over Holland and Belgium, the flak began appearing, somewhat sporadically at first, but then it got heavier as they approached Germany. Suddenly, approximately 40 FW190s appeared in their 10-o’clock high position, and roared in, guns firing. A favored tactic by the Germans was to attack from a higher position, rolling through the bomber formation, and spinning away and down to safety, avoiding as many of the defending .50-caliber machine guns as possible. No immediate casualties were suffered by Les’ squadron from the first attack of these Holland-based German fighters. As it turned out, however, this was only the beginning of a nightmarish engagement. For whatever reason, today the German Luftwaffe was out in full force. Les Rentmeester later reported that, for six full hours, from the time of crossing the coastline to the time of their return to the English Channel, the 8th Air Force bombers were under fighter attack. It is estimated that anywhere from 350-500 German defending fighters took part in this air battle of January 11, 1944. Next up were formations of twin-engine ME-110s and ME-210s, staying outside the bomber formations but firing at the bombers with cannons and wing mounted rockets. There 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame was very little fine-tuned aiming going on in these particular engagements, because the twin-engine defenders rarely got close to the bombers. Rather, the German tactic was designed simply to toss large-scale ammo and fireworks into the bomber formations. If a bomber happened to be hit, it would go down – these largescale munitions had incredible destructive power. But, often times, the defenders’ goal simply was to break up the formations, scatter the bombers, and then leave the stragglers and smaller groups of bombers to be picked off by the more nimble singleengine fighters, such as the ME-109s and the FW-190s. The air battle became chaotic. Another wave of FW-190s flashed through Les’ squadron. The gunners in his B-17 hit several of the attacking fighters, but one of those fighters that they hit then careened into the B-17 immediately off the wing of Les’ plane, slicing through it – both the American bomber and the German fighter, on fire and out of control, twisted slowly, helplessly, toward the ground below. Then, in quick succession, two more bombers in Les’ squadron were hit: one went into a flat spin, the other blew up in a massive explosion, apparently from a direct hit on its bomb-load. Fires on the ground, with thick black smoke in the form of funeral pyres, were everywhere, as were the littered frames of burned out airplanes, American and German. Just then, the gunners in Les’ plane reported a gaggle of 30-40 single-engine German fighters approaching their formation from 2-o’clock low. To the men in Les’ crew, their total destruction seemed imminent. Out of nowhere, a single intrepid P-51B Mustang flashed by. It dove into the gathering of German fighters, taking out two of the enemy fighters on its first pass. Then it swung around and reengaged the mass of German fighters, which scattered at the sight of the determined American fighter pilot. From despair to delicious euphoria, the bomber pilots cheered their “little friend” who saved the day. This single action, so unexpected by both friend and foe, blunted the fighter attack on the bomber formation. Later, as the bomber pilots who survived the mission reported back to their intelligence briefers, the men were able to learn the identity of their timely protector. Major James (Tex) Howard in his P-51 Mustang shot down 4-6 of the German fighters. He was suitably recognized for his courageous action with the Congressional Medal of Honor. But that was later. By the time that the B-17s in Les’ group reached their target, eight of his accompanying planes had been shot down, and most of the rest had become scattered. Les realized that he was pretty much flying alone now in the “low squadron” position, and he quickly eased his B-17 upward, so that it could slide into a gap left open in the lead squadron ahead. He might be the “tail-end Charlie” in that formation, but at least he was a part of a formation, any formation. And the bomber formation gave his plane strength and added protection from fighter attack. The group of B-17s turned at the IP into their bomb run, and the planes were turned over to the bombardiers to fly them to the target. Les’ plane had over 4000 pounds of incendiaries, and they hit the target squarely. His crew saw explosions, flames, and bursts of smoke leaping from the Focke-Wulf plant works. They had done their job.

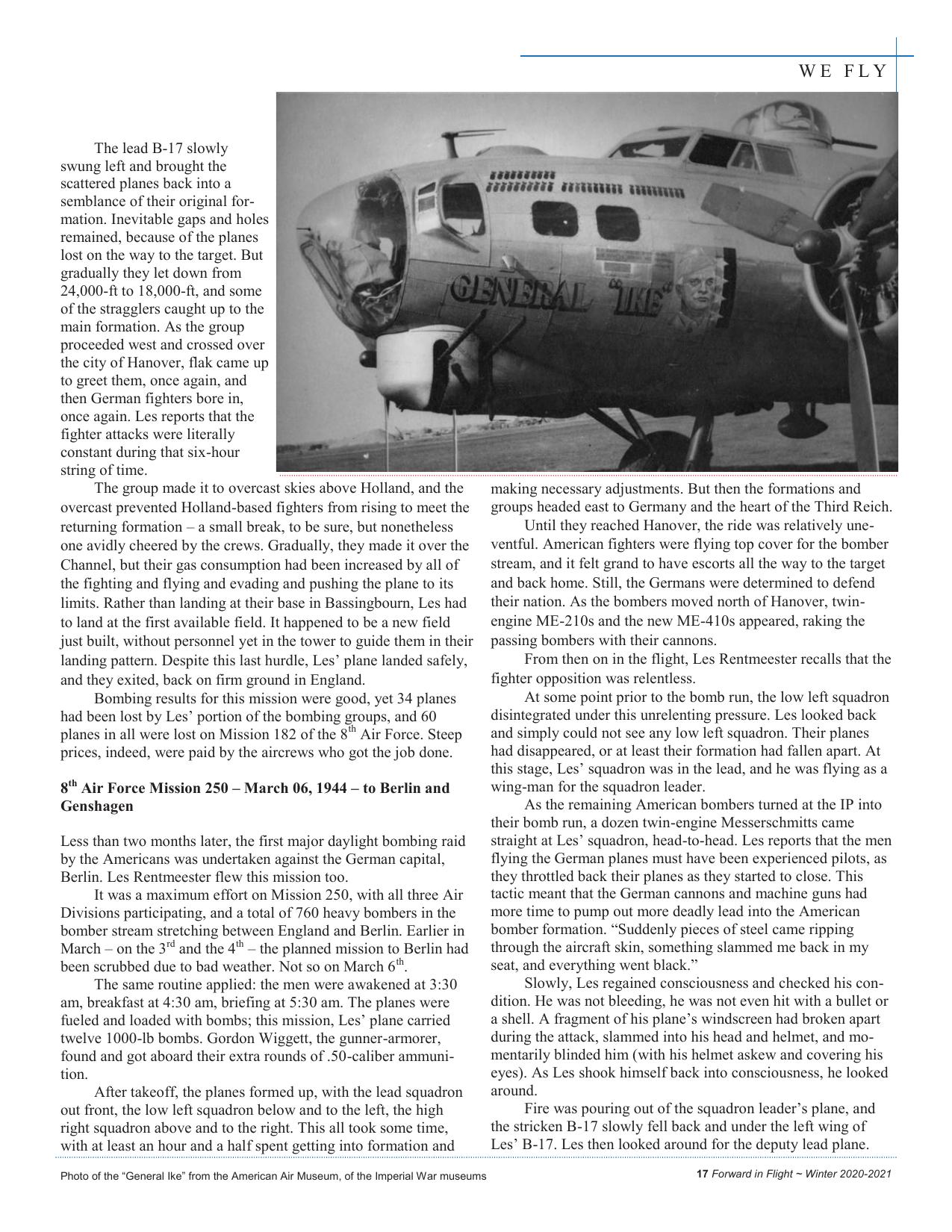

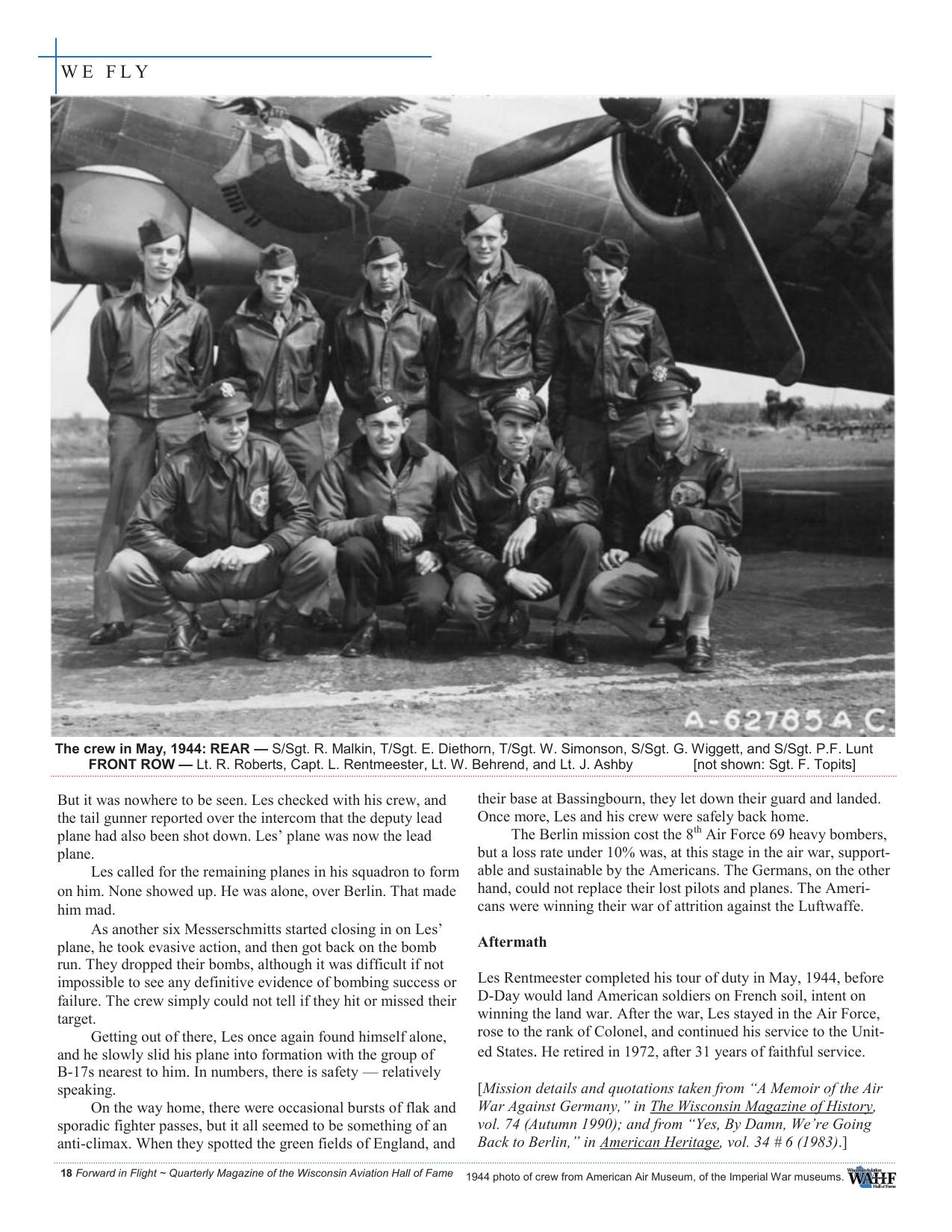

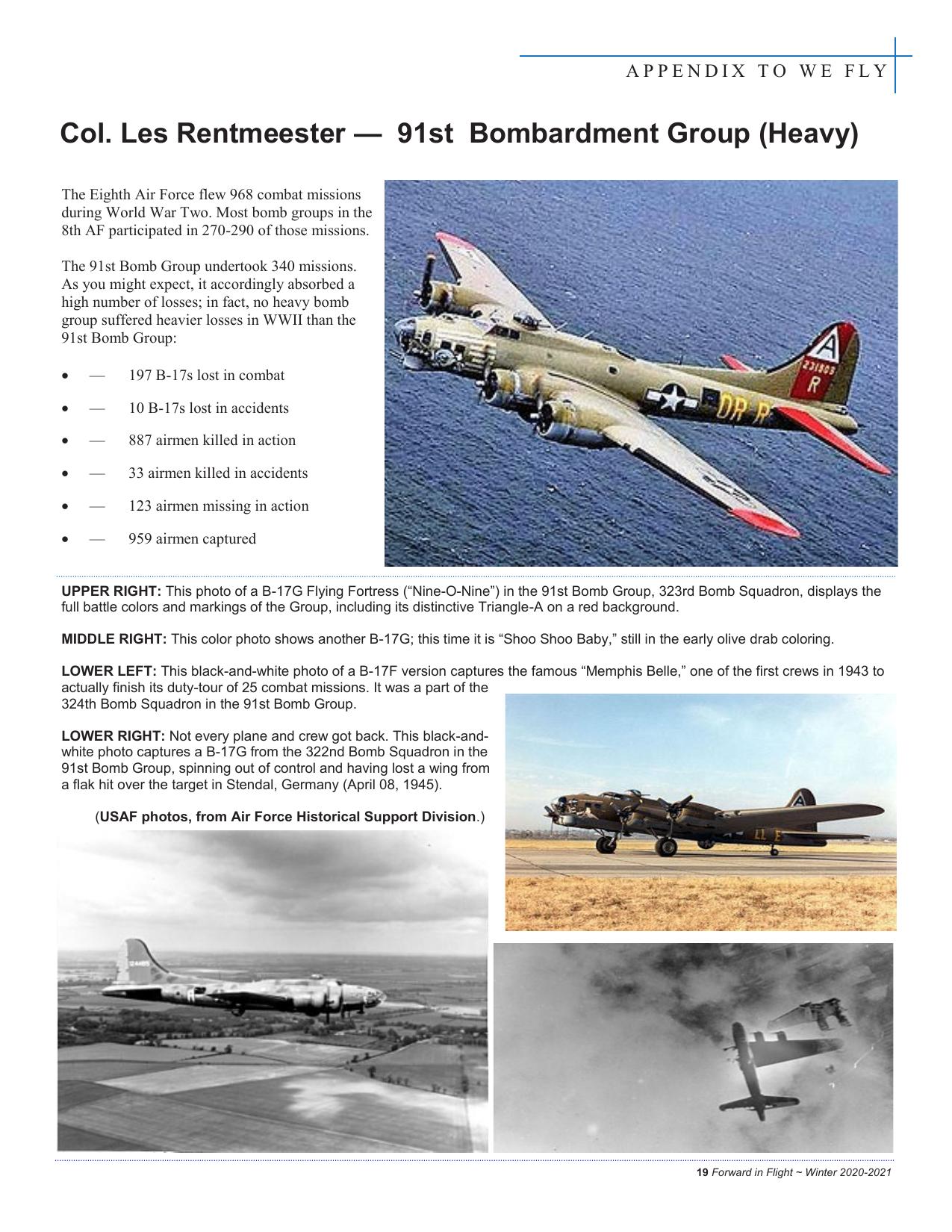

WE FLY The lead B-17 slowly swung left and brought the scattered planes back into a semblance of their original formation. Inevitable gaps and holes remained, because of the planes lost on the way to the target. But gradually they let down from 24,000-ft to 18,000-ft, and some of the stragglers caught up to the main formation. As the group proceeded west and crossed over the city of Hanover, flak came up to greet them, once again, and then German fighters bore in, once again. Les reports that the fighter attacks were literally constant during that six-hour string of time. The group made it to overcast skies above Holland, and the overcast prevented Holland-based fighters from rising to meet the returning formation – a small break, to be sure, but nonetheless one avidly cheered by the crews. Gradually, they made it over the Channel, but their gas consumption had been increased by all of the fighting and flying and evading and pushing the plane to its limits. Rather than landing at their base in Bassingbourn, Les had to land at the first available field. It happened to be a new field just built, without personnel yet in the tower to guide them in their landing pattern. Despite this last hurdle, Les’ plane landed safely, and they exited, back on firm ground in England. Bombing results for this mission were good, yet 34 planes had been lost by Les’ portion of the bombing groups, and 60 planes in all were lost on Mission 182 of the 8 th Air Force. Steep prices, indeed, were paid by the aircrews who got the job done. 8th Air Force Mission 250 – March 06, 1944 – to Berlin and Genshagen Less than two months later, the first major daylight bombing raid by the Americans was undertaken against the German capital, Berlin. Les Rentmeester flew this mission too. It was a maximum effort on Mission 250, with all three Air Divisions participating, and a total of 760 heavy bombers in the bomber stream stretching between England and Berlin. Earlier in March – on the 3rd and the 4th – the planned mission to Berlin had been scrubbed due to bad weather. Not so on March 6 th. The same routine applied: the men were awakened at 3:30 am, breakfast at 4:30 am, briefing at 5:30 am. The planes were fueled and loaded with bombs; this mission, Les’ plane carried twelve 1000-lb bombs. Gordon Wiggett, the gunner-armorer, found and got aboard their extra rounds of .50-caliber ammunition. After takeoff, the planes formed up, with the lead squadron out front, the low left squadron below and to the left, the high right squadron above and to the right. This all took some time, with at least an hour and a half spent getting into formation and Photo of the “General Ike” from the American Air Museum, of the Imperial War museums making necessary adjustments. But then the formations and groups headed east to Germany and the heart of the Third Reich. Until they reached Hanover, the ride was relatively uneventful. American fighters were flying top cover for the bomber stream, and it felt grand to have escorts all the way to the target and back home. Still, the Germans were determined to defend their nation. As the bombers moved north of Hanover, twinengine ME-210s and the new ME-410s appeared, raking the passing bombers with their cannons. From then on in the flight, Les Rentmeester recalls that the fighter opposition was relentless. At some point prior to the bomb run, the low left squadron disintegrated under this unrelenting pressure. Les looked back and simply could not see any low left squadron. Their planes had disappeared, or at least their formation had fallen apart. At this stage, Les’ squadron was in the lead, and he was flying as a wing-man for the squadron leader. As the remaining American bombers turned at the IP into their bomb run, a dozen twin-engine Messerschmitts came straight at Les’ squadron, head-to-head. Les reports that the men flying the German planes must have been experienced pilots, as they throttled back their planes as they started to close. This tactic meant that the German cannons and machine guns had more time to pump out more deadly lead into the American bomber formation. “Suddenly pieces of steel came ripping through the aircraft skin, something slammed me back in my seat, and everything went black.” Slowly, Les regained consciousness and checked his condition. He was not bleeding, he was not even hit with a bullet or a shell. A fragment of his plane’s windscreen had broken apart during the attack, slammed into his head and helmet, and momentarily blinded him (with his helmet askew and covering his eyes). As Les shook himself back into consciousness, he looked around. Fire was pouring out of the squadron leader’s plane, and the stricken B-17 slowly fell back and under the left wing of Les’ B-17. Les then looked around for the deputy lead plane. 17 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2020-2021