Growing up near Mount Horeb, Wisconsin, in the 1930s, my father, Arnold Ebneter, saw at least 10 airplanes flying overhead every day, a coincidence of geography and geology. Flights between Chicago and Minneapolis passed close to the dairy farm where he lived, and the farm contained Donald Rock, a monolith that dominated the countryside and made for an attractive waypoint for pilots in the days before electronic navigation.

Arnold seemed destined to be a pilot from the day he was born. By age six, he and his cousin Carl sported small versions of the leather helmets and goggles that Charles Lindbergh wore during his famous transatlantic crossing in 1927, which occurred exactly nine months prior to Arnold’s birth on February 21, 1928.

Arnold’s first flight occurred at the annual Fall Frolic in Mount Horeb when he was eight. Two barnstormers in biplanes were offering rides for one dollar per person, and, despite the steep price, Arnold’s father wanted a ride, too. The flight was only 15 minutes, but Arnold was thrilled at the sight of the ground receding as they climbed and marveled at the tiny houses from 1,000 feet above the ground. He was hooked for life.

Too young to take lessons, Arnold built model airplanes and devoured aviation magazines and books for the next several years. Building the models and learning what the different parts of an airplane did made him decide that he didn’t want to just be a pilot, he also wanted to design and build airplanes.

When Arnold was 11, his family gave up farming and moved to Portage, which from Arnold’s point of view had a crown jewel: a small airport. It wasn’t much in those days, just a little grass field about half-mile square, with a pilot lounge about the size of a two-car garage. The owners, Chet and Bob Mael, mowed two runways into the grass and bought a handful of small airplanes for flight instruction. By the time he was 14, Arnold spent many Saturdays at the airport, watching pilots take off and land and tagging after Chet as he prepared for a flight or refueled and repaired airplanes. During this time, Arnold added aircraft mechanic to his growing list of ambitions.

After earning $40 waiting tables and busing dishes at a restaurant in the summer of 1943, Arnold finally had enough money to start flight lessons. His first lesson was on September 13, 1943, in a Piper J-3 Cub. After several months of lessons, he was ready to solo on his sixteenth birthday, but he had yet to get his student pilot certificate, which required hitchhiking to Milwaukee due to fuel rationing during the war. Additional delays for weather pushed the date out further, but he finally soloed on April 2, 1944.

Arnold passed his private pilot checkride on July 24, 1946. His original plan had been to eventually become an airline pilot, but the release of thousands of military trained pilots back into the civilian workforce at the end of World War II put that idea on hold. Arnold didn’t mind—he moved onto working on his bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering.

He spent his first year of college at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, but the private school proved too expensive, so he switched to the University of Minnesota. The moved proved pivotal: Not only did he have more time to pursue his commercial pilot, instructor, and airframe mechanic certificates, he met a young freshman, Colleen, who he taught how to fly and later married.

In Minnesota, Arnold also began working on a research project with General Mills’s Aeronautical Research Laboratory. At first, his job involved flying aircraft that chased unmanned balloons carrying sensitive U.S. Navy instruments, but eventually, Arnold began flying the balloons as well. Many of the flights took place at White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico, and during one flight, he flew a balloon overnight for 12 hours from White Sands to near the town of Aspermont, Texas. He was the only person on board, and in the darkness that surrounded him for much of the flight, it was possible to believe that he was the only person left in the world. But after a few hours, he spotted small fires from oil operations and welcomed the connection to the ground. It was a good practice flight for what was to come later.

By now, it was 1952, and with the Korean War raging, Arnold had dropped out of college to work full time for General Mills. He’d obtained several draft deferments for his work with the Navy, but those were about to expire. He didn’t mind serving in the war, but he preferred that it be from a cockpit instead of the ground if possible. Fortunately, the Air Force needed pilots, and he entered the Aviation Cadet Training program at Lackland Air Force Base in late 1952.

On March 15, 1954, Arnold earned his Air Force pilot’s wings as a distinguished graduate from pilot training. After a quick dash north to marry Colleen, he reported to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, for fighter pilot training in the F-86, then the Air Force’s most advanced fighter. From there, he went to Foster Air Force Base near Victoria, Texas, and joined an operational fighter wing. A year later, his wing transitioned to flying the F-100, the Air Force’s first supersonic jet fighter.

Arnold’s wing was involved in demonstrating how to deploy fighter aircraft all over the world on short notice, something that is routine today, but was unheard of in the early 1950s. But before the wing could start to deploy, the pilots first had to learn how to refuel the F-100, which used a “probe-and-drogue” system commonly used later by the Navy. Arnold and the other pilots couldn’t see the probe, which was attached under the right wing of the F-100, leading to many cracked canopies and gouged fuselages before they figured things out.

Once they had mastered the basics of refueling, Arnold and five other pilots in his squadron participated in a simulated attack on the Panama Canal in the fall of 1956. The flight took eight hours and involved two aerial refuelings. By the time he landed, Arnold had been awake for more than 30 hours, and he had never been more exhausted. But like his 12-hour balloon flight, it was good practice for later.

After a few years of flying the F-100, Arnold entered an Air Force program that sent him to Texas A&M to complete his aeronautical engineering degree. As he considered a topic for his senior project, he stumbled over a short article about Juhani Heinonen, a Finnish pilot and engineer who in 1957 had set a world distance record for the C-1a class—an airplane using a combustion engine (as opposed to a rocket) and weighing no more than 500 kilograms. Heinonen had designed and built the record-setting airplane himself. The record of 1,767 miles seemed pretty pedestrian, and his faculty advisor agreed that Arnold could try to design an airplane that would beat that distance.

Arnold predicted his design would more than double the current record, and his paper that described the airplane’s major characteristics, such as wing layout, landing gear, and engine, won a student paper first place award from the organization that later became the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

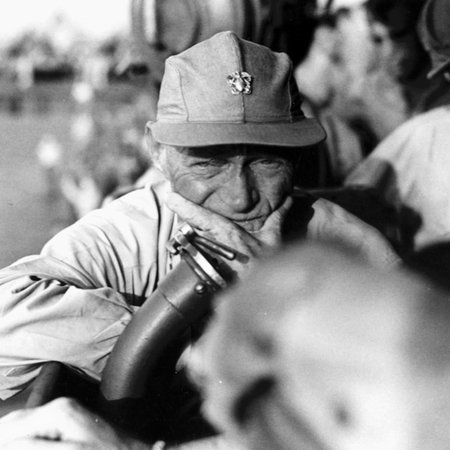

The first-place prize included $300 that Arnold planned to use to start building his record-setting airplane right away. But Arnold had plenty of distractions. The first was his growing family, with four daughters by 1962, which required the purchase of a Beechcraft Bonanza to replace the family’s Cessna 170. The second was his busy career as an F-100 pilot at England Air Force Base, Louisiana, where he again deployed all over the world, including Turkey and Vietnam. Then, after attending the Air Force Institute of Technology in Ohio for his master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, he requalified in the F-100 and deployed to Tuy Hoa, South Vietnam, in early 1968, where he flew 224 combat missions. After Vietnam, Arnold was stationed at Eglin Air Force Base in the Florida Panhandle.

While in Florida, Arnold fiddled with his record setter’s design and acquired some parts to use for the airplane. In 1973, he had his final assignment as an ROTC instructor at Parks College in Cahokia, Illinois, where he finally completed the powerplant portion of his mechanic’s certificate.

In 1974, Arnold retired from the Air Force and moved to Seattle to work for Boeing as a safety expert. But Seattle held new distractions to building his record-setter, which he began calling the E-1. Arnold began flying part-time as chief instructor pilot at a local airport, Harvey Airfield, and later became an FAA designated pilot examiner. During the 1980s, he restored a J-3 Cub for Colleen and transported fish in Alaska. During the 1990s, he flew a thunderstorm research aircraft in New Mexico.

Finally, in the mid-1990s, Arnold retired from Boeing to focus on completing the E-1. In 1999, with the E-1 about half finished, Colleen died unexpectedly. After recovering from that setback, Arnold began working on the E-1 in earnest, and in July 2005, the E-1 finally made its first flight. He then spent four years making refinements to increase the E-1’s speed.

By then, the record set in 1957 had been extended twice. In 1975, Edgar Lesher, a professor at the University of Michigan, used a pusher aircraft of his own design to extend the record to 1,835 miles. In 1984, Gary Hertzler, an engineer with Allied Signal (now Honeywell), used another pusher, a VariEze, to further extend the record to 2,214 miles.

The E-1 was ready in 2009, but the weather didn’t cooperate. A year later, everything came together.

On July 25, 2010, at 2:15 p.m., Arnold took off from Paine Field in Everett, Washington, carrying only essentials—59 gallons of fuel, two energy bars, and a quart of water. Since thunderstorms in the Midwest usually die down at night, he chose an afternoon takeoff so he could cross the Midwest overnight and then land the next morning in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

During his climb to 9,500 feet to cross the Cascade Mountains, his fuel flow meter and total fuel gauge failed. For the next 18 hours, he would have to guess how much fuel he had used by multiplying estimated burn rate and airborne time.

As he crossed the Cascades, the radio in his cramped cockpit seemed to have failed as well, but he finally contacted an air traffic controller in Eastern Washington. In Montana, a line of thunderstorms at a safe distance provided a spectacular light show as the sun set behind him. As the night wore on, a full moon rose, and the radio fell silent.

Passing through North Dakota, a headwind slowed Arnold’s progress and wasted precious fuel. Near Columbus, Ohio, not long after sunrise, the E-1’s engine burned the last remnants of fuel in the wings. The only fuel was now in the nine-gallon fuselage tank, but Arnold calculated he needed more than that to break the record.

He chose not to surrender. With clearer weather forecast ahead, he climbed up to 7,500 feet and found a tailwind that carried him the rest of the way to Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he landed after covering 2,328 miles in 18 hours and 15 minutes.

In addition to breaking the record, Arnold’s feat was chosen by the National Aeronautic Association as one of the “Ten Most Notable Aviation Records of 2010,” and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale bestowed the 2011 Louis Blériot medal on him, which may be given annually to pilots of the highest distance, speed, and altitude records in aircraft weighing less than 1,000 kilograms. In 2013, Arnold was inducted into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. The E-1 is now on display at the EAA Museum. Arnold retired from flying in 2019 and continues to reside in the Seattle area.