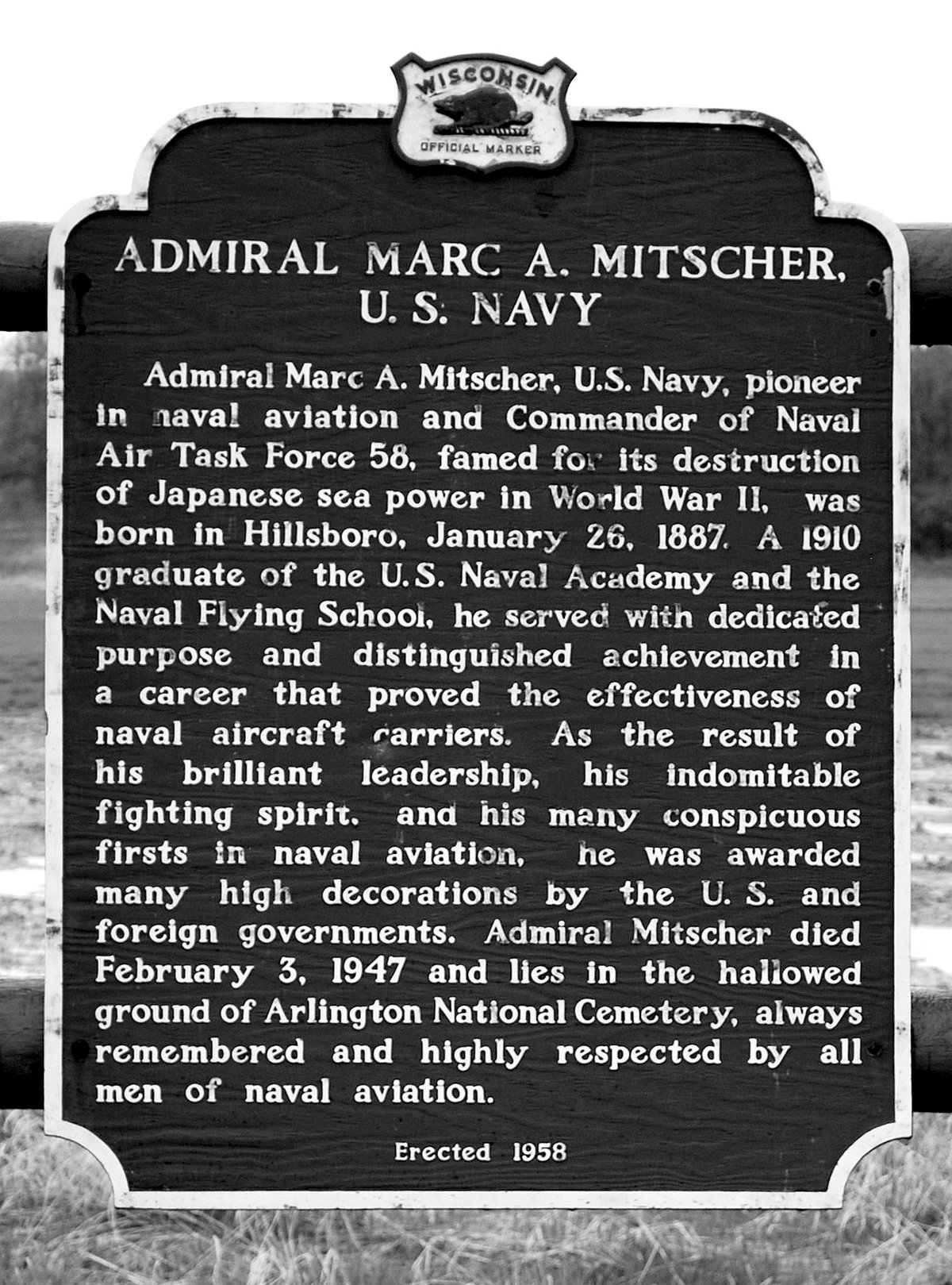

As unlikely as it seems that a young boy from the small Wisconsin community of Hillsboro could become the most important Naval aviator, tactical commander, and architect of the U.S. World War II victory in the Pacific, that was exactly the case with Marc Andrew “Pete” Mitscher.

Marc Mitscher was born on 26 January 1887 in Hillsboro, a small western Wisconsin city in Vernon County that was settled primarily by people of Czech heritage. When he was two years old, his parents Oscar and Myrta left Hillsboro, taking the family to Oklahoma where his father worked as an Indian agent during the western land boom of 1888–89. Records are unclear as to what the family did after that, but by the time young Marc Mitscher was ready to begin school, he was in Washington, D.C. and attended both elementary and secondary schools there before receiving an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA) at Annapolis in 1906.

After graduating USNA in 1910, he served in the surface Navy on several warships including the USS California based out of San Diego during the Mexican Campaign.

In 1915, Mitscher volunteered for service in the aviation branch and went to NAS (Naval Aeronautics Station) Pensacola in Florida where he learned to fly. He graduated on 2 June 1916, earning his “Wings of Gold” and the designation “Naval Aviator No. 33.” His first flying assignments were to armored cruisers (the Navy had no aircraft carriers at the time) where he flew floatplanes from catapults, performing the missions of reconnaissance and spotter for Naval gunfire. Mitscher must have made a favorable impression, because by 1919 he had been assigned to the Aviation Section in the office of the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington, D.C.

Navy Flying Boat Squadron Crosses the Atlantic in 1919

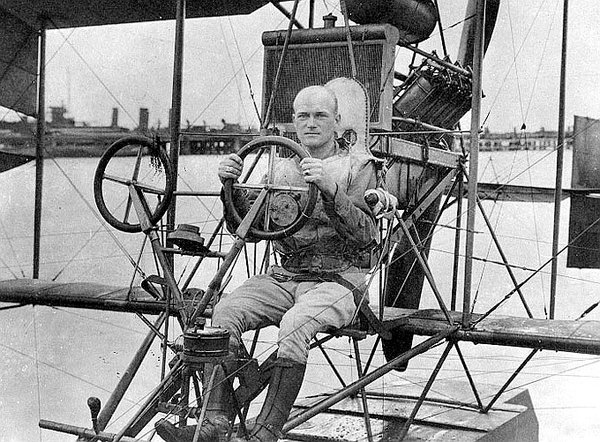

In 1919, as the Navy planned to cross the Atlantic by air, they selected Mitscher as one of the crewmembers, and he became part of a special three-airplane squadron that would attempt the first ever trans-Atlantic crossing in Navy Curtiss (NC) Flying Boats, known as “Nancy Boats.” Each “Nancy” had a crew of three, a wingspan of 126 feet, and was powered by four Liberty V-12 engines.

This was not to be a non-stop crossing, as was Lindbergh’s flight in 1927, but an effort with the full support of the U.S. Navy. Ships were positioned at 50-mile intervals along the course to aid with navigation, to observe and report weather to the flying boats, and to provide refueling. The three Navy flying boats were designated NC-1, NC-2, and NC-3, with Mitscher as the pilot of NC-1.

Flying conditions at the time were such that it took great physical endurance, as well as exceptional skill and perseverance to fly large flying boats at low altitude in rough weather. Heavy fog and rough seas forced down Mitscher’s plane (NC-1) and NC-3 near the Azores at the Atlantic mid-point, while NC-2 was able to continue to Portugal. Although not all three airplanes made it, the U.S. Navy squadron had succeeded in being the first to cross the Atlantic by air.

Although the squadron had completed its mission, Mitscher felt bitterly disappointed his airplane had not completed the entire flight. Nevertheless, the Navy awarded him the Navy Cross for his participation. (The Navy Cross is the Navy’s second highest award; second only to the Medal of Honor. This would be the first of three Navy Crosses Mitscher would receive during his career.) The citation on Mitscher’s Navy Cross read, “For distinguished service in the line of his profession as a member of the crew of the Seaplane NC-1, which made a long overseas flight from Newfoundland to the vicinity of the Azores in May 1919.”

Some have speculated that Mitscher’s disappointment at not making it across the Atlantic only increased the intensity with which he approached the rest of his Navy career, sharpening both his dedication and sense of duty.

Through the 1920s, Mitscher continued as a Naval aviator; flying, developing tactics, and helping draw up the blueprints for what would be the U.S. Navy that fought in World War II. In 1928, Mitscher made the first takeoff and landing on the USS Saratoga (CV-3), the ship that would be regarded as the Navy’s first “fast carrier.”

Mitscher continued to serve in the Navy’s air arm through the 1930s, honing doctrine and tactics, and by 1941 was sent to Norfolk to fit out and commission the USS Hornet (CV-12) and to become its first commanding officer. The Hornet took to sea in October 1941, only weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Mitscher Commands Doolittle Raid

Marc Mitscher’s first brush with glory in World War II came in April 1942 when he was selected to command and carry Jimmy Doolittle’s B-25 bombers within flying range of Tokyo. Although the Doolittle Raid did limited physical damage, the sheer boldness of a Naval task force approaching Tokyo that early in the war and launching a raid on the Japanese homeland was a stunning psychological victory for the U.S. After President Roosevelt hinted that Doolittle’s bombers had come from a secret base in “Shangri-La,” Mitscher’s Hornet became known as “Shangri-La,” and the name became so embedded in Navy mystique that later in the war, the Navy named an Essex-class carrier the USS Shangri-La (CV-38).

Mitscher also commanded the Hornet during the Battle of Midway in June 1942, where the Navy decisively defeated the Japanese fleet, sinking four of their six fleet aircraft carriers. Although the war in the Pacific would continue to be fought bitterly for three more years, the outcome was never in doubt after Midway.

After completing his assignment as commander of Hornet, Mitscher went on to command Patrol Wing Two, and then went to Guadalcanal to command all Navy, Army Air Force, Marine Corps, and New Zealand Air Force aviation assets in that battle. Navy Vice-admiral William “Bull” Halsey sent Mitscher to Guadalcanal because as Halsey put it, “Mitscher is a fighting fool that can handle the tough job.” Mitscher also commanded the operation that shot down Japanese Admiral Yamamoto on 18 April 1943.

The “Fast Carrier” Task Force

By 1944, Marc Mitscher was a Rear Admiral (two stars) and commanded what was to become Task Force 58, the Navy’s fast carrier strike force that brought the Japanese Navy to its knees. Early in WWII, Navy carriers had typically operated independently, or on special missions such as carrying the Doolittle Raid to within range of Tokyo. Mitscher had long been a strong advocate of concentrating the Navy’s carrier force into a powerful striking weapon, and after he took command of TF 58, the words “Mitscher” and “fast carrier task force” became synonymous.

Under Mitscher, TF 58 fought and won the Battles of the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf, the Battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and took the naval battle directly to the Japanese homeland and Tokyo.

Turn On Your Lights

Perhaps the most celebrated event of Mitscher’s career took place during the Battle of the Philippine Sea (also known as “The Marianas Turkey Shoot”). Mitscher made the daring decision to order all the carriers in his task force to turn on their lights to recover an alpha strike of more than 200 airplanes that had taken off in pursuit of the Japanese carrier force just before sunset. After sinking the carrier Hiyo, the returning airplanes could not have safely landed had the carriers not turned on their lights, a decision Mitscher made even though the action perilously exposed his carriers to attack by Japanese submarines.

Mitscher was beloved by the sailors and aviators who served under him largely because of decisions such as ordering those carriers to turn on their lights. He could have easily followed doctrine and gone “by the book,” maintaining blackout conditions while sacrificing the airborne aircraft and their pilots, but instead, recovering his pilots took priority.

Survives Kamikaze Attack

In May 1945, Admiral Mitscher used the USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) as his flagship while he commanded TF 58 during the Battle of Okinawa. On 11 May, two Japanese Kamikaze aircraft hit the Bunker Hill causing severe damage, killing more than 400 aviators and sailors. The second Kamikaze aircraft hit the flight deck just short of the Bunker Hill’s tower from where Mitscher commanded TF 58, destroying Mitscher’s sea cabin along with all his personal papers and clothing.

Damage to the Bunker Hill was so severe the ship was forced to retire from the battle, and Mitscher had to transfer command of TF 58 to USS Enterprise (CV-6), the most decorated flattop of WWII.

One incident from Mitscher’s time on board the Bunker Hill is both amusing and revealing. Late one night a signalman entered Mitscher’s sea cabin to report bogies had penetrated TF 58’s radar screen. The signalman later told his shipmates of his surprise that the tough-as-nails admiral was wearing what seemed to be a long-sleeved, sissified nightshirt much like a woman’s nightgown. When a few nights later, the same signalman again entered Mitscher’s sea cabin to deliver a critical message, he found Mitscher changing clothes. The signalman was shocked to discover that tattoos almost completely covered Mitscher’s body. Mitscher apparently wore the long nightshirt so no one would know.

As World War II progressed to its culmination in 1945, Mitscher’s fast carriers took the fight to the very shores of Japan, and by June 1945, bombers from Mitscher’s carriers were hitting strategic targets all across Japan, including Tokyo. It is notable that the first U.S. strike against Tokyo in 1942 had been launched from USS Hornet, the ship Mitscher commanded, and when carrier-launched aircraft once more returned to bomb Tokyo in 1945, they were again under Mitscher’s command.

Wisconsin Fathers of Airpower

Admiral Marc A. Mitscher spent his entire Naval career in aviation, and much of the Naval Air doctrine used in World War II was a direct result of his innovation, foresight, and experimentation. He was truly the architect of naval airpower in World War II, and it is worth noting that both General Billy Mitchell, the architect of Air Force airpower, and Admiral Marc Mitscher, the architect of Naval airpower, were born in Wisconsin.

In 1946, President Truman offered Admiral Marc Mitscher the position of Chief of Naval Operations, but Mitscher turned it down to instead become Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Fleet because of his desire to be at sea with sailors and aviators instead of contending with the political battles of Washington, D.C.

Marc Mitscher died of a heart attack in 1947 while commanding the Atlantic Fleet. During his funeral the famed World War II destroyer commander Admiral Arleigh “31 knot” Burke gave Mitscher perhaps his greatest tribute during the eulogy: “He spoke in a low voice and used few words. Yet, so great was his concern for his people—for their training and welfare in peacetime and their rescue in combat—that he was able to obtain their final ounce of effort and loyalty, without which he could not have become the preeminent carrier force commander in the world. A bulldog of a fighter, a strategist blessed with an uncanny ability to foresee his enemy’s next move, and a lifelong searcher after truth and trout streams, he was above all else—perhaps above all other—a Naval Aviator.”

The International Aerospace Hall of Fame invested Marc Mitscher as a member in 1989, and the National Aviation Hall of Fame at Dayton, Ohio, has also enshrined him. The U.S. Navy has named an Arleigh Burke-class Aegis destroyer in his honor, the USS Mitscher (DDG-57).