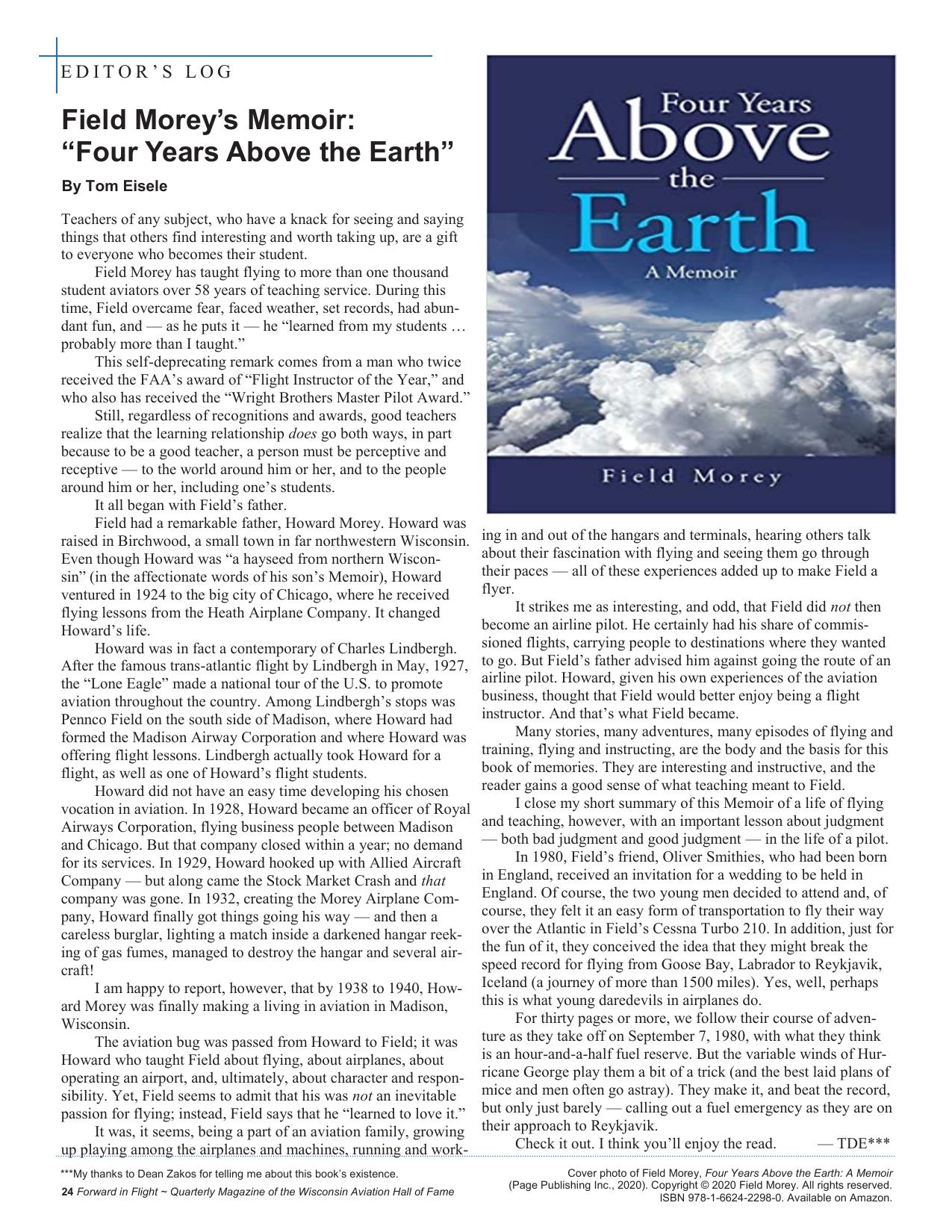

Forward in Flight - Summer 2021

Volume 19, Issue 2 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Summer 2021

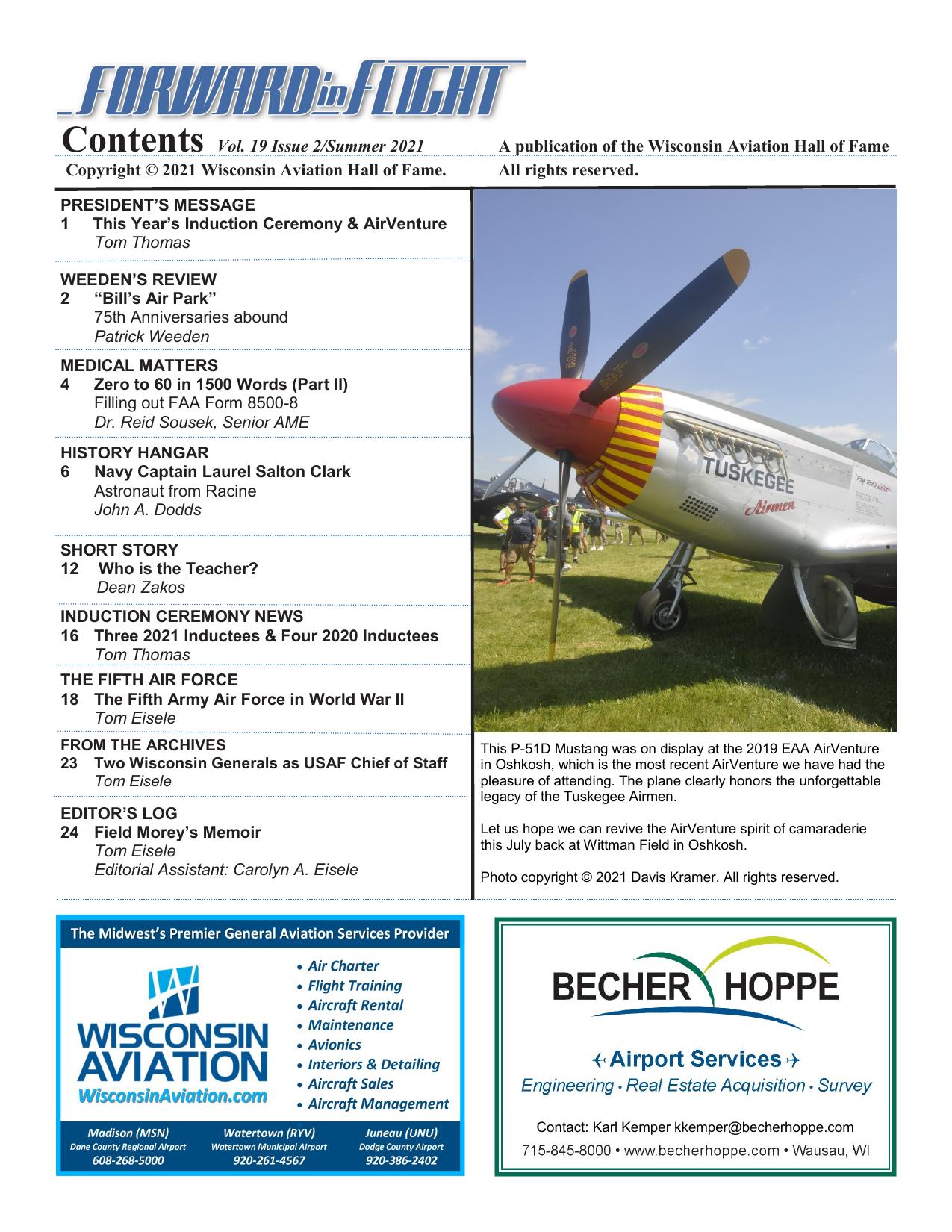

Contents Vol. 19 Issue 2/Summer 2021 Copyright © 2021 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All rights reserved. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 1 This Year’s Induction Ceremony & AirVenture Tom Thomas WEEDEN’S REVIEW 2 “Bill’s Air Park” 75th Anniversaries abound Patrick Weeden MEDICAL MATTERS 4 Zero to 60 in 1500 Words (Part II) Filling out FAA Form 8500-8 Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME HISTORY HANGAR 6 Navy Captain Laurel Salton Clark Astronaut from Racine John A. Dodds SHORT STORY 12 Who is the Teacher? Dean Zakos INDUCTION CEREMONY NEWS 16 Three 2021 Inductees & Four 2020 Inductees Tom Thomas THE FIFTH AIR FORCE 18 The Fifth Army Air Force in World War II Tom Eisele FROM THE ARCHIVES 23 Two Wisconsin Generals as USAF Chief of Staff Tom Eisele EDITOR’S LOG 24 Field Morey’s Memoir Tom Eisele Editorial Assistant: Carolyn A. Eisele This P-51D Mustang was on display at the 2019 EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh, which is the most recent AirVenture we have had the pleasure of attending. The plane clearly honors the unforgettable legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen. Let us hope we can revive the AirVenture spirit of camaraderie this July back at Wittman Field in Oshkosh. Photo copyright © 2021 Davis Kramer. All rights reserved. Contact: Karl Kemper kkemper@becherhoppe.com

President’s Message By Tom Thomas Spring has come to Wisconsin and, with the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, hangar doors are opening. The activity is most welcome. Although wearing masks in some places is still encouraged, moving around and going to the airport are a reality we all can now enjoy. With the development of the vaccines, things are moving in the right direction. Over the years, I have learned that the purpose of long-range planning is to have something to deviate from when we get there. (Airport Master Plans are one of the best ‘bad examples’ of these types of challenges.) In order for plans to be viable, they have to be living documents. That means they need to incorporate flexibility when systems and events occur which require us to adjust. In aviation, more so than the other transportation modes, COVID-19 has given us all that opportunity to adjust our plans. Ultimately, our planning evolves into what we make of it when the time comes. This Summer 2021 issue is special as it includes the new WAHF Inductees for 2021 (and for 2020, because of adjusted plans), and it also covers how EAA’s AirVenture 2021 is shaping up. This year’s Induction Ceremony in October will induct both the 2021 and the 2020 class members (a total of seven people). We would like to thank all of you who have nominated individuals over the years since the first Induction Ceremony in 1986. We have many Wisconsinites who have done much in and with aviation over the years. We have WAHF members all across the state (and many outside Wisconsin) who know who those accomplished people are. Some of our “Wisconsin Aviation Heroes” include flight instructors, airplane mechanics, airline employees, airport managers, flight surgeons, and our Flight -for-Life helicopter crews and military pilots (to name a few). One of your benefits of being a WAHF member is that you can nominate individuals for induction into your Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. If the individual you nominate isn’t selected, the WAHF Board keeps the nomination and includes them in future evaluations. They are living documents in that the nominator can add additional information (including photos) at any time after the nominator has submitted the original document. Photographs are helpful in the process, as they can give additional insight into the message you present. The Forms for Forward in Flight the only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s aviation events. Tom Eisele, editor W8863 U.S. Highway 12 Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-9762 513-484-0394 t.d.eisele@att.net The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. Lodi Airport photo from WI DOT Aeronautics 2000 Airport Photos file. Lodi Airport, where 2021 inductee Dan Knutson soloed on his 16th birthday, and later passed his Private Pilot’s Flight Check. nominating are on our website, which we are in the process of updating. If you have questions about the nomination process, you can contact any WAHF Board member (listed on the back cover of FIF) for help. Along those lines, from time to time, WAHF Board members retire or move out of the state. If you would be interested in serving on the Board, please send us a resume and cover letter. When openings come up, we’ll contact every person who has expressed an interest. With our office headquarters being located at the Brodhead Airport, it will be more convenient for learning about WAHF itself and seeing some of our displays when visiting the Kelch Museum. This issue also gives some details about the coming 2021 AirVenture. We lost last year due to COVID-19, but the development and implementation of vaccines mean that, come July, the gates in Oshkosh will open to EAA members from Wisconsin and around the world. Those from outside the country are likely to have to quarantine; as the time approaches, the specific criteria for participants and visitors will be widely disseminated. (Tom Eisele’s notice on page 22 gives a good outline of what to expect.) The EAA will be taking additional measures to ensure that any pandemic virus risks are minimized for all attending. We in Wisconsin are truly blessed to be able to host the annual AirVenture gatherings at Wittman Field. To everyone interested in aviation, Oshkosh is the place to visit. I hope to see you at AirVenture 2021! Cover: The launch of the ill-fated Columbia Space Shuttle in 2003. John Dodds’ story on Astronaut Laurel Clark begins at page 6. Photo courtesy of NASA.

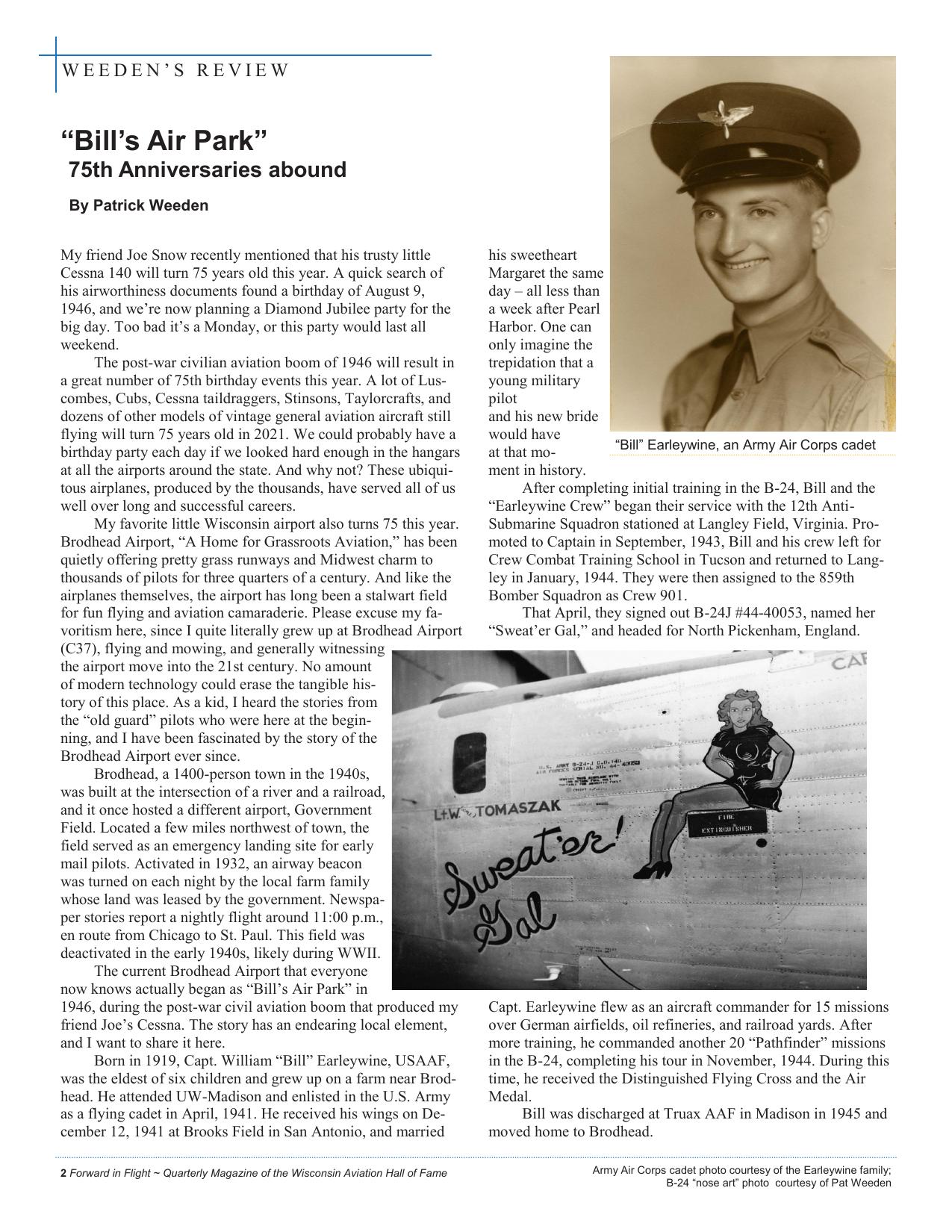

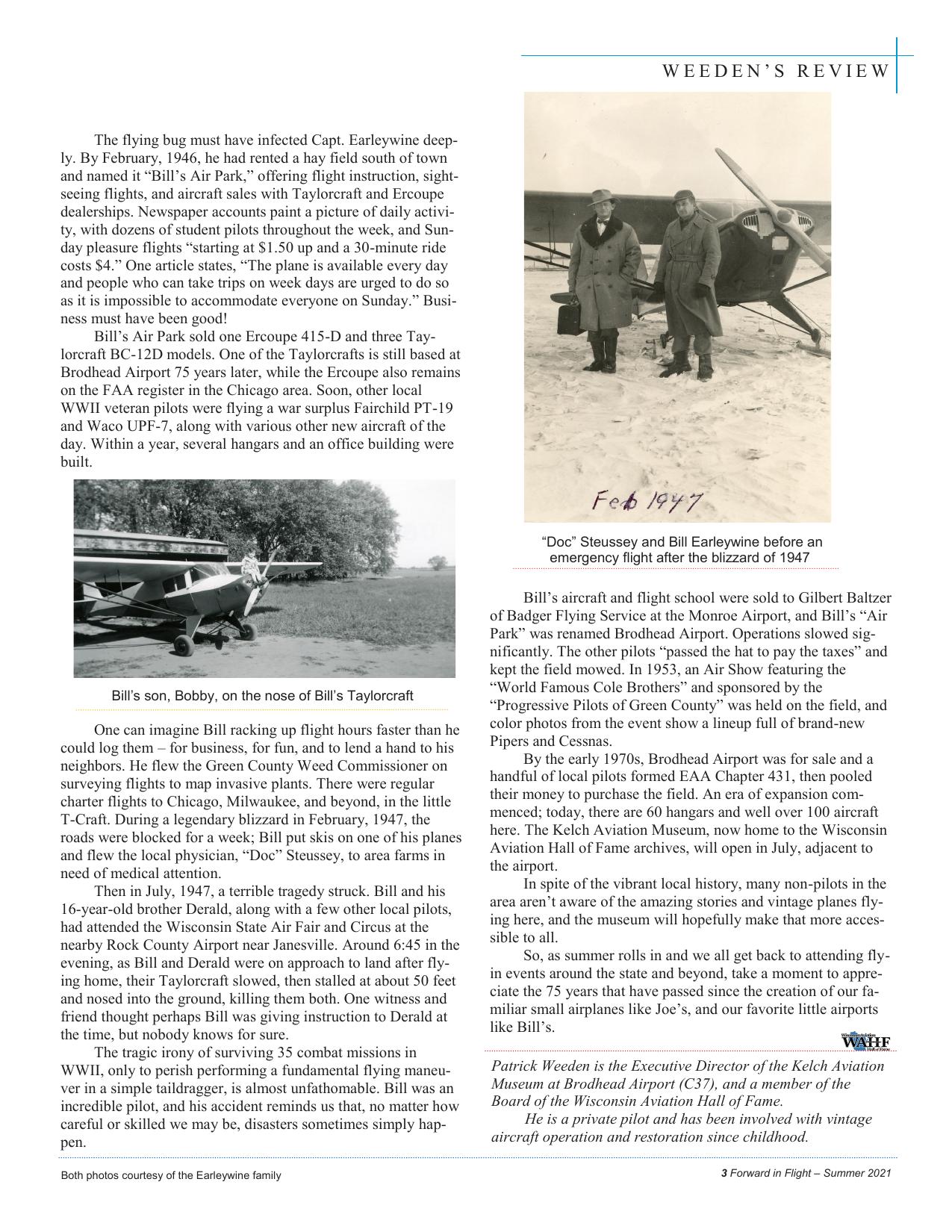

WEEDEN’S REVIEW “Bill’s Air Park” 75th Anniversaries abound By Patrick Weeden My friend Joe Snow recently mentioned that his trusty little Cessna 140 will turn 75 years old this year. A quick search of his airworthiness documents found a birthday of August 9, 1946, and we’re now planning a Diamond Jubilee party for the big day. Too bad it’s a Monday, or this party would last all weekend. The post-war civilian aviation boom of 1946 will result in a great number of 75th birthday events this year. A lot of Luscombes, Cubs, Cessna taildraggers, Stinsons, Taylorcrafts, and dozens of other models of vintage general aviation aircraft still flying will turn 75 years old in 2021. We could probably have a birthday party each day if we looked hard enough in the hangars at all the airports around the state. And why not? These ubiquitous airplanes, produced by the thousands, have served all of us well over long and successful careers. My favorite little Wisconsin airport also turns 75 this year. Brodhead Airport, “A Home for Grassroots Aviation,” has been quietly offering pretty grass runways and Midwest charm to thousands of pilots for three quarters of a century. And like the airplanes themselves, the airport has long been a stalwart field for fun flying and aviation camaraderie. Please excuse my favoritism here, since I quite literally grew up at Brodhead Airport (C37), flying and mowing, and generally witnessing the airport move into the 21st century. No amount of modern technology could erase the tangible history of this place. As a kid, I heard the stories from the “old guard” pilots who were here at the beginning, and I have been fascinated by the story of the Brodhead Airport ever since. Brodhead, a 1400-person town in the 1940s, was built at the intersection of a river and a railroad, and it once hosted a different airport, Government Field. Located a few miles northwest of town, the field served as an emergency landing site for early mail pilots. Activated in 1932, an airway beacon was turned on each night by the local farm family whose land was leased by the government. Newspaper stories report a nightly flight around 11:00 p.m., en route from Chicago to St. Paul. This field was deactivated in the early 1940s, likely during WWII. The current Brodhead Airport that everyone now knows actually began as “Bill’s Air Park” in 1946, during the post-war civil aviation boom that produced my friend Joe’s Cessna. The story has an endearing local element, and I want to share it here. Born in 1919, Capt. William “Bill” Earleywine, USAAF, was the eldest of six children and grew up on a farm near Brodhead. He attended UW-Madison and enlisted in the U.S. Army as a flying cadet in April, 1941. He received his wings on December 12, 1941 at Brooks Field in San Antonio, and married 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame his sweetheart Margaret the same day – all less than a week after Pearl Harbor. One can only imagine the trepidation that a young military pilot and his new bride would have “Bill” Earleywine, an Army Air Corps cadet at that moment in history. After completing initial training in the B-24, Bill and the “Earleywine Crew” began their service with the 12th AntiSubmarine Squadron stationed at Langley Field, Virginia. Promoted to Captain in September, 1943, Bill and his crew left for Crew Combat Training School in Tucson and returned to Langley in January, 1944. They were then assigned to the 859th Bomber Squadron as Crew 901. That April, they signed out B-24J #44-40053, named her “Sweat’er Gal,” and headed for North Pickenham, England. Capt. Earleywine flew as an aircraft commander for 15 missions over German airfields, oil refineries, and railroad yards. After more training, he commanded another 20 “Pathfinder” missions in the B-24, completing his tour in November, 1944. During this time, he received the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. Bill was discharged at Truax AAF in Madison in 1945 and moved home to Brodhead. Army Air Corps cadet photo courtesy of the Earleywine family; B-24 “nose art” photo courtesy of Pat Weeden

WEEDEN’S REVIEW The flying bug must have infected Capt. Earleywine deeply. By February, 1946, he had rented a hay field south of town and named it “Bill’s Air Park,” offering flight instruction, sightseeing flights, and aircraft sales with Taylorcraft and Ercoupe dealerships. Newspaper accounts paint a picture of daily activity, with dozens of student pilots throughout the week, and Sunday pleasure flights “starting at $1.50 up and a 30-minute ride costs $4.” One article states, “The plane is available every day and people who can take trips on week days are urged to do so as it is impossible to accommodate everyone on Sunday.” Business must have been good! Bill’s Air Park sold one Ercoupe 415-D and three Taylorcraft BC-12D models. One of the Taylorcrafts is still based at Brodhead Airport 75 years later, while the Ercoupe also remains on the FAA register in the Chicago area. Soon, other local WWII veteran pilots were flying a war surplus Fairchild PT-19 and Waco UPF-7, along with various other new aircraft of the day. Within a year, several hangars and an office building were built. “Doc” Steussey and Bill Earleywine before an emergency flight after the blizzard of 1947 Bill’s son, Bobby, on the nose of Bill’s Taylorcraft One can imagine Bill racking up flight hours faster than he could log them – for business, for fun, and to lend a hand to his neighbors. He flew the Green County Weed Commissioner on surveying flights to map invasive plants. There were regular charter flights to Chicago, Milwaukee, and beyond, in the little T-Craft. During a legendary blizzard in February, 1947, the roads were blocked for a week; Bill put skis on one of his planes and flew the local physician, “Doc” Steussey, to area farms in need of medical attention. Then in July, 1947, a terrible tragedy struck. Bill and his 16-year-old brother Derald, along with a few other local pilots, had attended the Wisconsin State Air Fair and Circus at the nearby Rock County Airport near Janesville. Around 6:45 in the evening, as Bill and Derald were on approach to land after flying home, their Taylorcraft slowed, then stalled at about 50 feet and nosed into the ground, killing them both. One witness and friend thought perhaps Bill was giving instruction to Derald at the time, but nobody knows for sure. The tragic irony of surviving 35 combat missions in WWII, only to perish performing a fundamental flying maneuver in a simple taildragger, is almost unfathomable. Bill was an incredible pilot, and his accident reminds us that, no matter how careful or skilled we may be, disasters sometimes simply happen. Both photos courtesy of the Earleywine family Bill’s aircraft and flight school were sold to Gilbert Baltzer of Badger Flying Service at the Monroe Airport, and Bill’s “Air Park” was renamed Brodhead Airport. Operations slowed significantly. The other pilots “passed the hat to pay the taxes” and kept the field mowed. In 1953, an Air Show featuring the “World Famous Cole Brothers” and sponsored by the “Progressive Pilots of Green County” was held on the field, and color photos from the event show a lineup full of brand-new Pipers and Cessnas. By the early 1970s, Brodhead Airport was for sale and a handful of local pilots formed EAA Chapter 431, then pooled their money to purchase the field. An era of expansion commenced; today, there are 60 hangars and well over 100 aircraft here. The Kelch Aviation Museum, now home to the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame archives, will open in July, adjacent to the airport. In spite of the vibrant local history, many non-pilots in the area aren’t aware of the amazing stories and vintage planes flying here, and the museum will hopefully make that more accessible to all. So, as summer rolls in and we all get back to attending flyin events around the state and beyond, take a moment to appreciate the 75 years that have passed since the creation of our familiar small airplanes like Joe’s, and our favorite little airports like Bill’s. Patrick Weeden is the Executive Director of the Kelch Aviation Museum at Brodhead Airport (C37), and a member of the Board of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. He is a private pilot and has been involved with vintage aircraft operation and restoration since childhood. 3 Forward in Flight – Summer 2021

MEDICAL MATTERS Zero to 60 in 1500 Words Filling out FAA Form 8500-8 (Part II) Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME In the last article, we covered the components of the FAA Form 8500-8 that are completed by the airman when logging into the MedXpress website. We will continue going through the 60+ items on this FAA form, but this time we will focus on what your AME is entering and evaluating. Once you provide your AME with the confirmation number and the AME enters this into the Aerospace Medical Certification Subsystem, it is “game on.” By this, I mean the exam is started and the AME is required to submit the exam. From the FAA’s side of things, this event will show up as an exam. If the confirmation number is not entered/submitted, an exam has not occurred from the FAA’s point of view. This clarification above is important, as it is the starting point for many FAA disease protocols. One notable area I can’t stress enough is that, with each exam, the FAA is authorized to search the National Driver’s Registry, thus alerting the FAA to any motor vehicle actions, such as DUIs. Even if the ultimate legal outcome of a traffic stop is changed to a lesser charge (or even dismissed), the motor vehicle action is documented and visible to the FAA. Another time it may be important that an exam has occurred, is when another exam is initiated within 90 days. The AME will not be able to issue a certificate if a previous exam was performed within the last 90 days. The intent of this restriction is to prevent an airman from seeing one AME -- and possibly not liking what the AME is evaluating -- and then going to see another AME and possibly withholding information. In my experience, in two cases where the 90 day restriction became an issue for my pilots, there were valid explanations. In one case, an airman was in my clinic part-way through an exam when he got an urgent call to pick his child up at school. He had to leave the clinic with an incomplete exam. Subsequently, we were not able to coordinate schedules within the required 14day time frame for the mandatory exam submission. He did reschedule with me four weeks later, but the AMCS system did not allow me to issue my report. The solution was that we deferred his exam and we contacted the Aeromedical Certification Division (AMCD) with our explanation of the circumstances. Once the specifics were discussed, the AMCD did issue a certificate. The other case where the 90-day restriction for two exams came into play was a high school student who saw me for a 3rd class exam. He was interested in starting his flight training and working towards his private certificate. Two months after the exam, he found out that he was accepted to college for the school’s aviation program. A requirement of this program was 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame having a 1st class medical certification. Therefore, when he was seen for the 1st class examination, the AMCS did not allow issuance (due to the earlier 3rd class exam within 60 days). The student met all criteria for 1st class certification, so the exam was deferred and AMCD notified. AMCD determined that he did meet the criteria and a 1st class certificate was granted and mailed to the airman. While we are discussing these timing issues, we should note: if an online MedXpress application is started but not completed by the airman, it will be automatically deleted by the system in 30 days. It will appear as though no application was started. If the application is completed by the airman, and a confirmation number generated, this confirmation must be used within 60 days, or the application will be deleted. Now, shifting gears to Form 8500-8 itself, let’s consider items # 21 and onward. Question 21 is height and question 22 is weight. Height is recorded in inches and weight in pounds. The AMCS system automatically calculates a BMI (Body Mass Index) but it does not appear to document this anywhere on the final form. There are no specific standards for height and weight. However, the AME guide does state: “Although there are no medical standards for height, exceptionally short individuals may not be able to effectively reach all flight controls and must fly specially modified aircraft. If required, the FAA will place operational limitations on the pilot certificate.” Questions 23 and 24 are about Statements of Demonstrated Ability (SODA). To receive a SODA, the airman must generally undergo a practical test at the Flight Standards District Office. Some possible examples of where a SODA may be granted, would be the following: missing a portion of a limb, color vision deficit, or monovision. A famous historical example of an airman with Monovision who was granted a SODA is Wiley Post. Next, we move to the “hands on” portion of the physical exam. Numbers 25 to 34 cover the head and neck, similar to the exam your family doctor does at a yearly physical. The next few numbers move on to the heart, lung, abdominal exam -- again similar to your family doctor’s exam techniques. Unfortunately, the FAA included # 39 - Anus and # 41 G-U (genitourinary) system on the Form 8500-8. Luckily, though, a close read of # 41 in the AME Guide will find that the “pelvic exam is performed only at the applicant’s option or if indicated by specific history or physical findings.” Similar word-

MEDICAL MATTERS ing is noted for # 39, Digital Rectal Examination techniques. Of the more than one thousand exams I have done, I have yet to have a pilot opt in for these portions of the exam! With the exception of # 44 - Identifying body marks, scars, or, tattoos, the rest of the exam is pretty straight-forward. Many pilots are not expecting to be asked about scars or tattoos. In general, the documentation of these tattoos is done so as to assist body identification purposes in the event of an accident or fatality. The same applies to scars, although in some cases it will remind an airman of a surgery he forgot to document. Next up on the form are vision and hearing testing. While these are next on the form, in my clinic these are performed first by a nurse or assistant. The hearing guidelines are fairly straight-forward. The airman must be able to hear an average conversational voice at 6 feet. Alternatively, formal audiometric testing may be performed. There needs to be less than a 30 to 40 dB hearing loss, depending on the frequency tested. Vision testing may be one of the more nerve-racking items for many pilots (over fear of not meeting the standards). The standards for distance vision are 20/20 for 1st and 2nd class applicants, while 3rd class applicants need to be 20/40. This may be completed with or without correction. Near vision standards are 20/40 for all classes. For pilots over age 50 and seeking 1st or 2nd class certification, intermediate vision is also tested and must be a minimum 20/40. Near vision is tested at 16 inches from the eye and intermediate vision is 32 inches from the eye. This would be considered a loose equivalent to looking at a chart for near vision and looking at the panel for intermediate vision. “Phoria” testing is a confusing topic to many. A “phoria” refers to difficulty lining the eyes up on a single object. Therefore, a phoria may lead to double vision. Not to be confused with a “Tropia,” which is an eye misalignment that is always present. A phoria is not always present. A phoria may become more prominent when fatigued. Numerous options for testing color vision are allowed by the FAA. It may be as simple as Ishihara color plates or something as fancy as an automated device. However, only certain vision testing devices are authorized for use by the FAA. In my clinics, we use a Titmus Vision Screener. This desktop device allows us to test all vision standards including distance, near, intermediate, color, and phoria testing. In some cases, we will use the Snellen wall chart for distance testing or the Jaeger near vision card. # 55 is blood pressure which should not be over 155 mmHg systolic or 95 mm Hg diastolic. If you do take blood pressure medication, be sure to take it as usual on the day of the exam. I have had a few cases where an airman forgot to take his medication and we were pushing close to the 155/95 limit. Block 60 is where the rubber hits the road for AMEs. This is where we are required to comment on anything positive or requiring explanation from the first 59 items. # 56 is pulse, which is tested in a seated position. # 57 is a urinalysis specifically looking for protein and sugar in the urine. Presence of protein may be an indication of kidney disease and presence of sugar may be due to diabetes. While some pilots are subjected to random drug screens, the urine test for medical certification is just a simple urinalysis. # 58, an EKG, is required for 1st class applicants once at age 35 and then every year at age 40. The EKG is not routinely required for 2nd or 3rd class applicants. Some 2nd and 3rd class pilots may have EKGs required as part of a Special Issuance requirement, but it is not required as part of the standard exam. # 59 is a blank for “Other Tests Given.” Rarely do I document anything in this section, as most comments will go in block 60. Block 60 is where the rubber hits the road for AMEs. This is where we are required to comment on anything positive or requiring clarification from the first 59 items. Here we clarify any PRNC (Previously Reported No Change) documented by the airman. The remaining four items include documenting any disqualifying defects and documenting whether a certificate was issued. With all blanks completed, I click the “Check for Errors” tab and the AMCS system will verify that all blanks are indeed completed. For some numerical values, such as vision, the system will show an error if the value is out of normal limits. If no errors are detected, the exam is submitted electronically to the FAA and your medical certificate can be printed. The original certificate is signed by both the airman and the AME. With the exam submitted and your certificate in hand, you are ready to go fly. The FAA does technically have 60 days to review the exam and request any additional information. Only in severe cases, such as where the AME incorrectly issued a certificate, is the certificate revoked. [Dr. Reid Sousek is an FAA-designated Senior Aviation Medical Examiner, who offers Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 Pilot Medical Exams; and an HIMS AME, for drug/alcohol exams. Dr. Sousek has offices near Oshkosh and Menasha.] 5 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2021

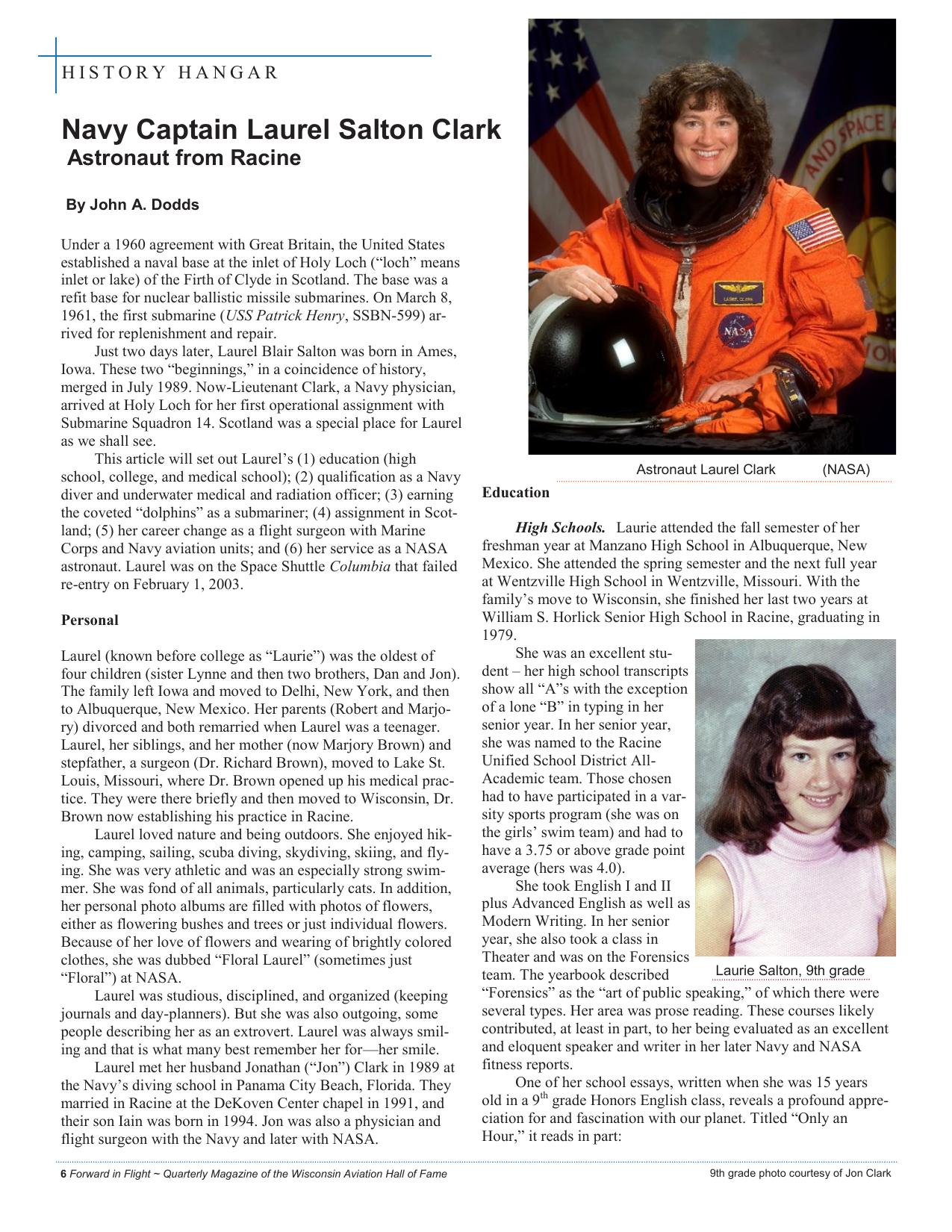

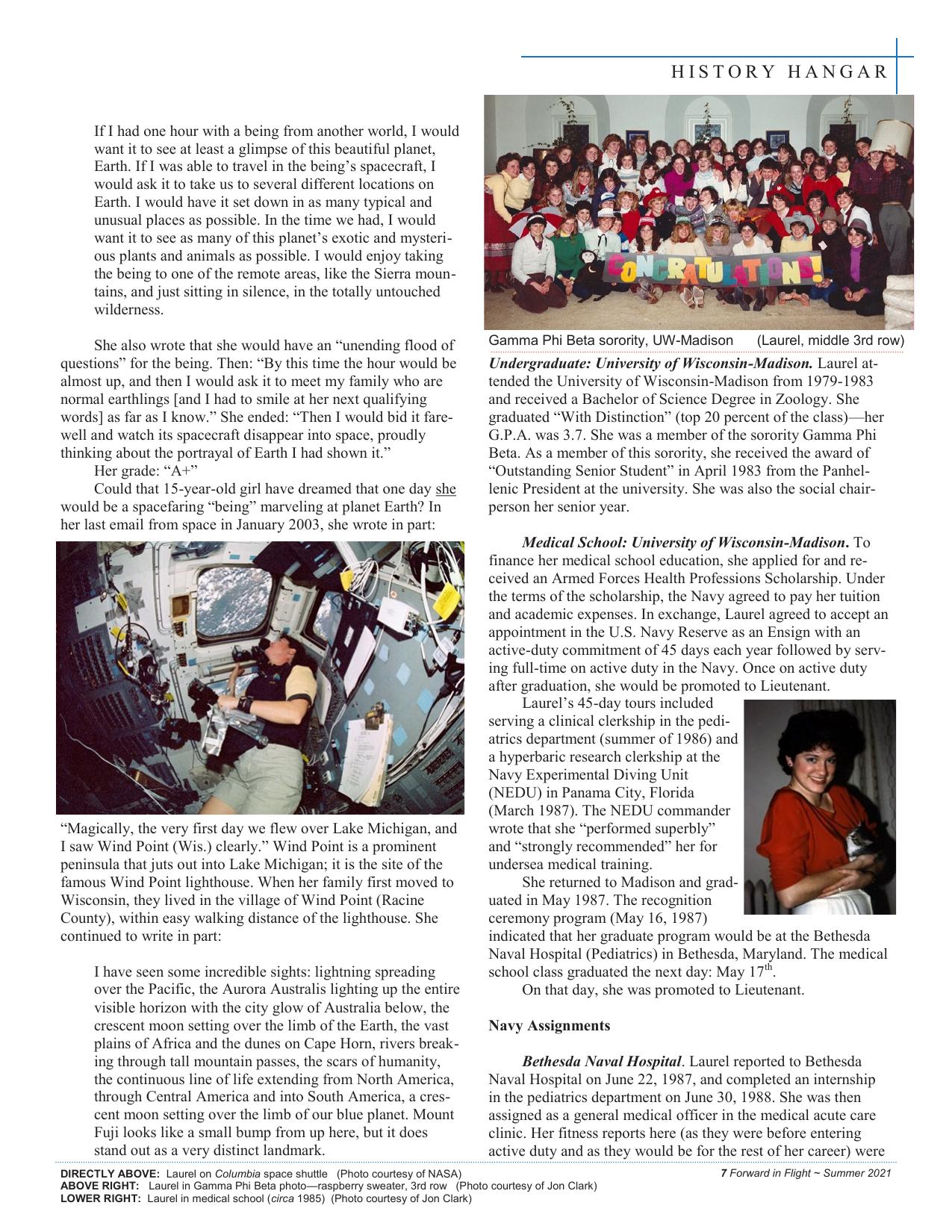

HISTORY HANGAR Navy Captain Laurel Salton Clark Astronaut from Racine By John A. Dodds Under a 1960 agreement with Great Britain, the United States established a naval base at the inlet of Holy Loch (“loch” means inlet or lake) of the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. The base was a refit base for nuclear ballistic missile submarines. On March 8, 1961, the first submarine (USS Patrick Henry, SSBN-599) arrived for replenishment and repair. Just two days later, Laurel Blair Salton was born in Ames, Iowa. These two “beginnings,” in a coincidence of history, merged in July 1989. Now-Lieutenant Clark, a Navy physician, arrived at Holy Loch for her first operational assignment with Submarine Squadron 14. Scotland was a special place for Laurel as we shall see. This article will set out Laurel’s (1) education (high school, college, and medical school); (2) qualification as a Navy diver and underwater medical and radiation officer; (3) earning the coveted “dolphins” as a submariner; (4) assignment in Scotland; (5) her career change as a flight surgeon with Marine Corps and Navy aviation units; and (6) her service as a NASA astronaut. Laurel was on the Space Shuttle Columbia that failed re-entry on February 1, 2003. Personal Laurel (known before college as “Laurie”) was the oldest of four children (sister Lynne and then two brothers, Dan and Jon). The family left Iowa and moved to Delhi, New York, and then to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her parents (Robert and Marjory) divorced and both remarried when Laurel was a teenager. Laurel, her siblings, and her mother (now Marjory Brown) and stepfather, a surgeon (Dr. Richard Brown), moved to Lake St. Louis, Missouri, where Dr. Brown opened up his medical practice. They were there briefly and then moved to Wisconsin, Dr. Brown now establishing his practice in Racine. Laurel loved nature and being outdoors. She enjoyed hiking, camping, sailing, scuba diving, skydiving, skiing, and flying. She was very athletic and was an especially strong swimmer. She was fond of all animals, particularly cats. In addition, her personal photo albums are filled with photos of flowers, either as flowering bushes and trees or just individual flowers. Because of her love of flowers and wearing of brightly colored clothes, she was dubbed “Floral Laurel” (sometimes just “Floral”) at NASA. Laurel was studious, disciplined, and organized (keeping journals and day-planners). But she was also outgoing, some people describing her as an extrovert. Laurel was always smiling and that is what many best remember her for—her smile. Laurel met her husband Jonathan (“Jon”) Clark in 1989 at the Navy’s diving school in Panama City Beach, Florida. They married in Racine at the DeKoven Center chapel in 1991, and their son Iain was born in 1994. Jon was also a physician and flight surgeon with the Navy and later with NASA. 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Astronaut Laurel Clark (NASA) Education High Schools. Laurie attended the fall semester of her freshman year at Manzano High School in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She attended the spring semester and the next full year at Wentzville High School in Wentzville, Missouri. With the family’s move to Wisconsin, she finished her last two years at William S. Horlick Senior High School in Racine, graduating in 1979. She was an excellent student – her high school transcripts show all “A”s with the exception of a lone “B” in typing in her senior year. In her senior year, she was named to the Racine Unified School District AllAcademic team. Those chosen had to have participated in a varsity sports program (she was on the girls’ swim team) and had to have a 3.75 or above grade point average (hers was 4.0). She took English I and II plus Advanced English as well as Modern Writing. In her senior year, she also took a class in Theater and was on the Forensics Laurie Salton, 9th grade team. The yearbook described “Forensics” as the “art of public speaking,” of which there were several types. Her area was prose reading. These courses likely contributed, at least in part, to her being evaluated as an excellent and eloquent speaker and writer in her later Navy and NASA fitness reports. One of her school essays, written when she was 15 years old in a 9th grade Honors English class, reveals a profound appreciation for and fascination with our planet. Titled “Only an Hour,” it reads in part: 9th grade photo courtesy of Jon Clark

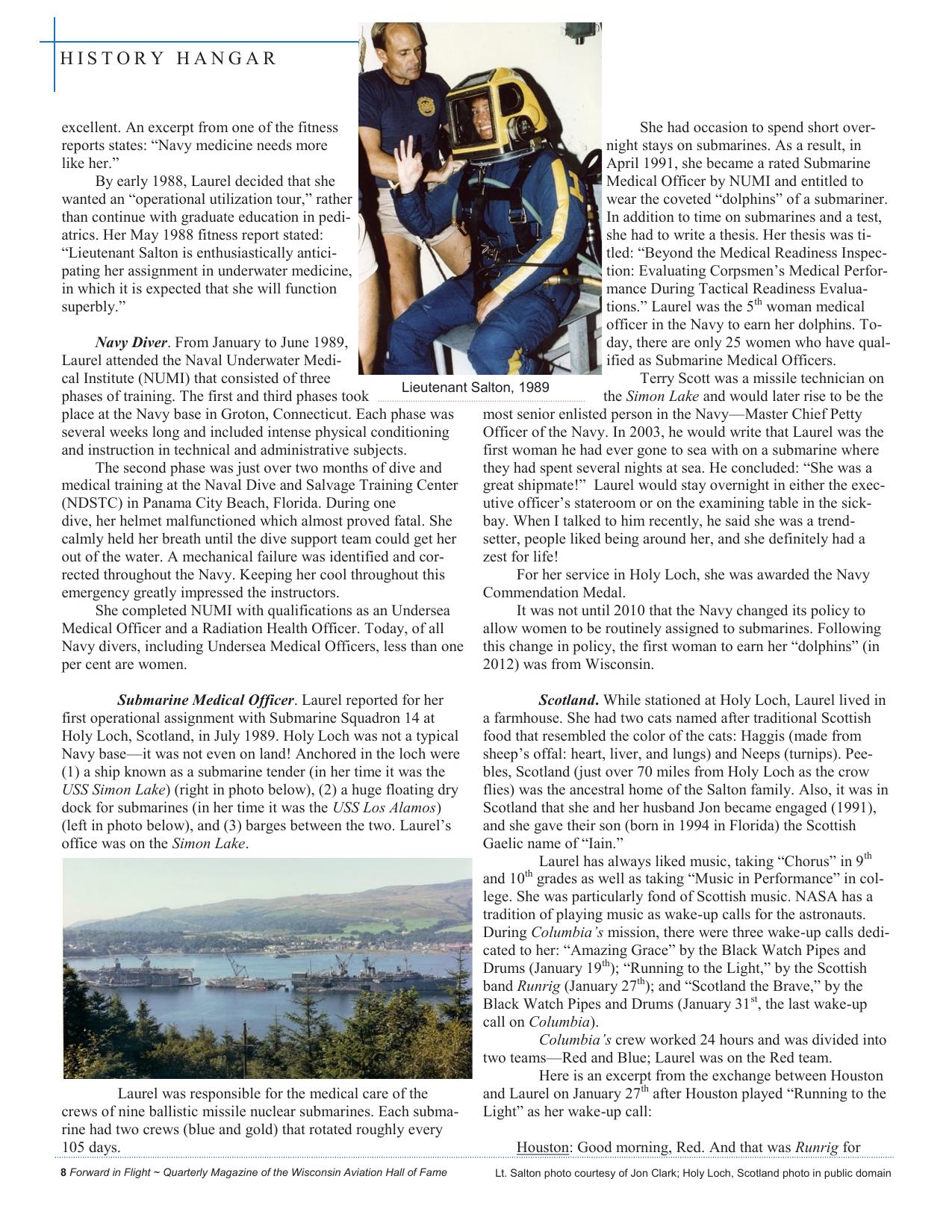

HISTORY HANGAR If I had one hour with a being from another world, I would want it to see at least a glimpse of this beautiful planet, Earth. If I was able to travel in the being’s spacecraft, I would ask it to take us to several different locations on Earth. I would have it set down in as many typical and unusual places as possible. In the time we had, I would want it to see as many of this planet’s exotic and mysterious plants and animals as possible. I would enjoy taking the being to one of the remote areas, like the Sierra mountains, and just sitting in silence, in the totally untouched wilderness. She also wrote that she would have an “unending flood of questions” for the being. Then: “By this time the hour would be almost up, and then I would ask it to meet my family who are normal earthlings [and I had to smile at her next qualifying words] as far as I know.” She ended: “Then I would bid it farewell and watch its spacecraft disappear into space, proudly thinking about the portrayal of Earth I had shown it.” Her grade: “A+” Could that 15-year-old girl have dreamed that one day she would be a spacefaring “being” marveling at planet Earth? In her last email from space in January 2003, she wrote in part: “Magically, the very first day we flew over Lake Michigan, and I saw Wind Point (Wis.) clearly.” Wind Point is a prominent peninsula that juts out into Lake Michigan; it is the site of the famous Wind Point lighthouse. When her family first moved to Wisconsin, they lived in the village of Wind Point (Racine County), within easy walking distance of the lighthouse. She continued to write in part: I have seen some incredible sights: lightning spreading over the Pacific, the Aurora Australis lighting up the entire visible horizon with the city glow of Australia below, the crescent moon setting over the limb of the Earth, the vast plains of Africa and the dunes on Cape Horn, rivers breaking through tall mountain passes, the scars of humanity, the continuous line of life extending from North America, through Central America and into South America, a crescent moon setting over the limb of our blue planet. Mount Fuji looks like a small bump from up here, but it does stand out as a very distinct landmark. Gamma Phi Beta sorority, UW-Madison (Laurel, middle 3rd row) Undergraduate: University of Wisconsin-Madison. Laurel attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison from 1979-1983 and received a Bachelor of Science Degree in Zoology. She graduated “With Distinction” (top 20 percent of the class)—her G.P.A. was 3.7. She was a member of the sorority Gamma Phi Beta. As a member of this sorority, she received the award of “Outstanding Senior Student” in April 1983 from the Panhellenic President at the university. She was also the social chairperson her senior year. Medical School: University of Wisconsin-Madison. To finance her medical school education, she applied for and received an Armed Forces Health Professions Scholarship. Under the terms of the scholarship, the Navy agreed to pay her tuition and academic expenses. In exchange, Laurel agreed to accept an appointment in the U.S. Navy Reserve as an Ensign with an active-duty commitment of 45 days each year followed by serving full-time on active duty in the Navy. Once on active duty after graduation, she would be promoted to Lieutenant. Laurel’s 45-day tours included serving a clinical clerkship in the pediatrics department (summer of 1986) and a hyperbaric research clerkship at the Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) in Panama City, Florida (March 1987). The NEDU commander wrote that she “performed superbly” and “strongly recommended” her for undersea medical training. She returned to Madison and graduated in May 1987. The recognition ceremony program (May 16, 1987) indicated that her graduate program would be at the Bethesda Naval Hospital (Pediatrics) in Bethesda, Maryland. The medical school class graduated the next day: May 17th. On that day, she was promoted to Lieutenant. Navy Assignments Bethesda Naval Hospital. Laurel reported to Bethesda Naval Hospital on June 22, 1987, and completed an internship in the pediatrics department on June 30, 1988. She was then assigned as a general medical officer in the medical acute care clinic. Her fitness reports here (as they were before entering active duty and as they would be for the rest of her career) were DIRECTLY ABOVE: Laurel on Columbia space shuttle (Photo courtesy of NASA) ABOVE RIGHT: Laurel in Gamma Phi Beta photo—raspberry sweater, 3rd row (Photo courtesy of Jon Clark) LOWER RIGHT: Laurel in medical school (circa 1985) (Photo courtesy of Jon Clark) 7 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2021

HISTORY HANGAR excellent. An excerpt from one of the fitness reports states: “Navy medicine needs more like her.” By early 1988, Laurel decided that she wanted an “operational utilization tour,” rather than continue with graduate education in pediatrics. Her May 1988 fitness report stated: “Lieutenant Salton is enthusiastically anticipating her assignment in underwater medicine, in which it is expected that she will function superbly.” She had occasion to spend short overnight stays on submarines. As a result, in April 1991, she became a rated Submarine Medical Officer by NUMI and entitled to wear the coveted “dolphins” of a submariner. In addition to time on submarines and a test, she had to write a thesis. Her thesis was titled: “Beyond the Medical Readiness Inspection: Evaluating Corpsmen’s Medical Performance During Tactical Readiness Evaluations.” Laurel was the 5th woman medical officer in the Navy to earn her dolphins. ToNavy Diver. From January to June 1989, day, there are only 25 women who have qualLaurel attended the Naval Underwater Mediified as Submarine Medical Officers. cal Institute (NUMI) that consisted of three Terry Scott was a missile technician on Lieutenant Salton, 1989 phases of training. The first and third phases took the Simon Lake and would later rise to be the place at the Navy base in Groton, Connecticut. Each phase was most senior enlisted person in the Navy—Master Chief Petty several weeks long and included intense physical conditioning Officer of the Navy. In 2003, he would write that Laurel was the and instruction in technical and administrative subjects. first woman he had ever gone to sea with on a submarine where The second phase was just over two months of dive and they had spent several nights at sea. He concluded: “She was a medical training at the Naval Dive and Salvage Training Center great shipmate!” Laurel would stay overnight in either the exec(NDSTC) in Panama City Beach, Florida. During one utive officer’s stateroom or on the examining table in the sickdive, her helmet malfunctioned which almost proved fatal. She bay. When I talked to him recently, he said she was a trendcalmly held her breath until the dive support team could get her setter, people liked being around her, and she definitely had a out of the water. A mechanical failure was identified and corzest for life! rected throughout the Navy. Keeping her cool throughout this For her service in Holy Loch, she was awarded the Navy emergency greatly impressed the instructors. Commendation Medal. She completed NUMI with qualifications as an Undersea It was not until 2010 that the Navy changed its policy to Medical Officer and a Radiation Health Officer. Today, of all allow women to be routinely assigned to submarines. Following Navy divers, including Undersea Medical Officers, less than one this change in policy, the first woman to earn her “dolphins” (in per cent are women. 2012) was from Wisconsin. Submarine Medical Officer. Laurel reported for her first operational assignment with Submarine Squadron 14 at Holy Loch, Scotland, in July 1989. Holy Loch was not a typical Navy base—it was not even on land! Anchored in the loch were (1) a ship known as a submarine tender (in her time it was the USS Simon Lake) (right in photo below), (2) a huge floating dry dock for submarines (in her time it was the USS Los Alamos) (left in photo below), and (3) barges between the two. Laurel’s office was on the Simon Lake. Laurel was responsible for the medical care of the crews of nine ballistic missile nuclear submarines. Each submarine had two crews (blue and gold) that rotated roughly every 105 days. 8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Scotland. While stationed at Holy Loch, Laurel lived in a farmhouse. She had two cats named after traditional Scottish food that resembled the color of the cats: Haggis (made from sheep’s offal: heart, liver, and lungs) and Neeps (turnips). Peebles, Scotland (just over 70 miles from Holy Loch as the crow flies) was the ancestral home of the Salton family. Also, it was in Scotland that she and her husband Jon became engaged (1991), and she gave their son (born in 1994 in Florida) the Scottish Gaelic name of “Iain.” Laurel has always liked music, taking “Chorus” in 9th th and 10 grades as well as taking “Music in Performance” in college. She was particularly fond of Scottish music. NASA has a tradition of playing music as wake-up calls for the astronauts. During Columbia’s mission, there were three wake-up calls dedicated to her: “Amazing Grace” by the Black Watch Pipes and Drums (January 19th); “Running to the Light,” by the Scottish band Runrig (January 27th); and “Scotland the Brave,” by the Black Watch Pipes and Drums (January 31st, the last wake-up call on Columbia). Columbia’s crew worked 24 hours and was divided into two teams—Red and Blue; Laurel was on the Red team. Here is an excerpt from the exchange between Houston and Laurel on January 27th after Houston played “Running to the Light” as her wake-up call: Houston: Good morning, Red. And that was Runrig for Lt. Salton photo courtesy of Jon Clark; Holy Loch, Scotland photo in public domain

HISTORY HANGAR Upon her return from this deployment, Laurel became the flight surgeon for the higher-level command at Yuma: Marine Aircraft Group 13. During her time in Yuma, she had a considerable amount of flying time in a T-38 Talon jet. She also soloed in a helicopter but did not get a license. Upon leaving Yuma in June 1994, she was again awarded the Navy Commendation Medal. Her second operational assignment as a flight surgeon was at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. Pensacola provides training for Navy and Marine flight officers. Laurel was a flight surgeon for Training Wing (VT) 86. For her tour of duty there, July 1994 to July 1996, she was awarded the Navy Commendation Medal for the third time. National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA) Jon, Iain, Laurel (NASA) Laurel and “Running to the Light.” Good morning. Laurel: Good morning, Houston. Runrig is one of my favorite bands from Scotland, which is where my husband and I got engaged. It’s where my family is from. Sending out love to my husband who’s been a great dad and to my son Iain. Can’t wait to see you guys in a few days. Flight Surgeon. While her squadron commander was supportive of women medical personnel on submarines, that sentiment was not shared by higher levels in the Navy’s submarine force. With diminished prospects for future submarine service, Laurel, ever resilient, decided to become a flight surgeon. From June 1991 to February 1992, she attended the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute (NAMI) in Pensacola, Florida. At the completion of this training, she became a qualified flight surgeon. She reported to her first operational assignment in March 1992 to a Marine attack squadron (VMA- 211) at the Marine Corps air base in Yuma, Arizona. The squadron’s planes were the AV-8B Harrier II Night Attack, a vertical take-off and landing jet. While there, she was promoted to Lieutenant Commander and received an appointment in the Regular Navy. She went on a 6-month deployment (May-November 1993) with the squadron to Iwakuni Marine Corps Air Station in Japan. The air station is located a little over an hour’s drive south of Hiroshima on the main Japanese island of Honshu. Since the jet is a single-seat jet; Laurel flew on a refueling tanker, the KC-10 Extender. Laurel took the stunning photo (below) of the Harrier jets over Wake Island. VMA-211 over Wake Island. Photo by Laurel Clark (Photo courtesy of Jon Clark) In a two-step, highly competitive process (pre-screening by the Navy and selection by NASA), Laurel became a NASA astronaut candidate in May 1996. Astronaut classes are given names; her class was the “Sardines” because of its size (her class of 44 was the largest). After completing the Astronaut Candidate Training Program on April 14, 1998, she officially became an astronaut and “eligible for assignment on human space flight.” She worked in the Astronaut Office Payloads and Habitability Branch. In addition, she became a fully qualified crew member of the T-38 Talon jet aircraft and was promoted to Astronaut Laurel Clark (NASA) Commander. Space Transportation System (STS). The STS consists of three main components: (1) the main external fuel tank (orange in color) that provides the fuel (liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen) for the orbiter’s three main engines; (2) the orbiter, which is the white airplane-like vehicle that houses the crew, is attached to the main external fuel tank; and (3) two white solid rocket boosters (SRBs) that are also attached to the main external fuel tank. The term “Space Shuttle” is popularly used to refer to just the orbiter. There were 135 numbered STS missions. The mission numbers did not always coincide with the sequence of launch because some missions were delayed. For example, the designation for Laurel’s mission was STS-107, although it actually was the 113th STS mission. Columbia was the first orbiter and was launched on April 12, 1981. STS-107 was its 28th mission. 9 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2021

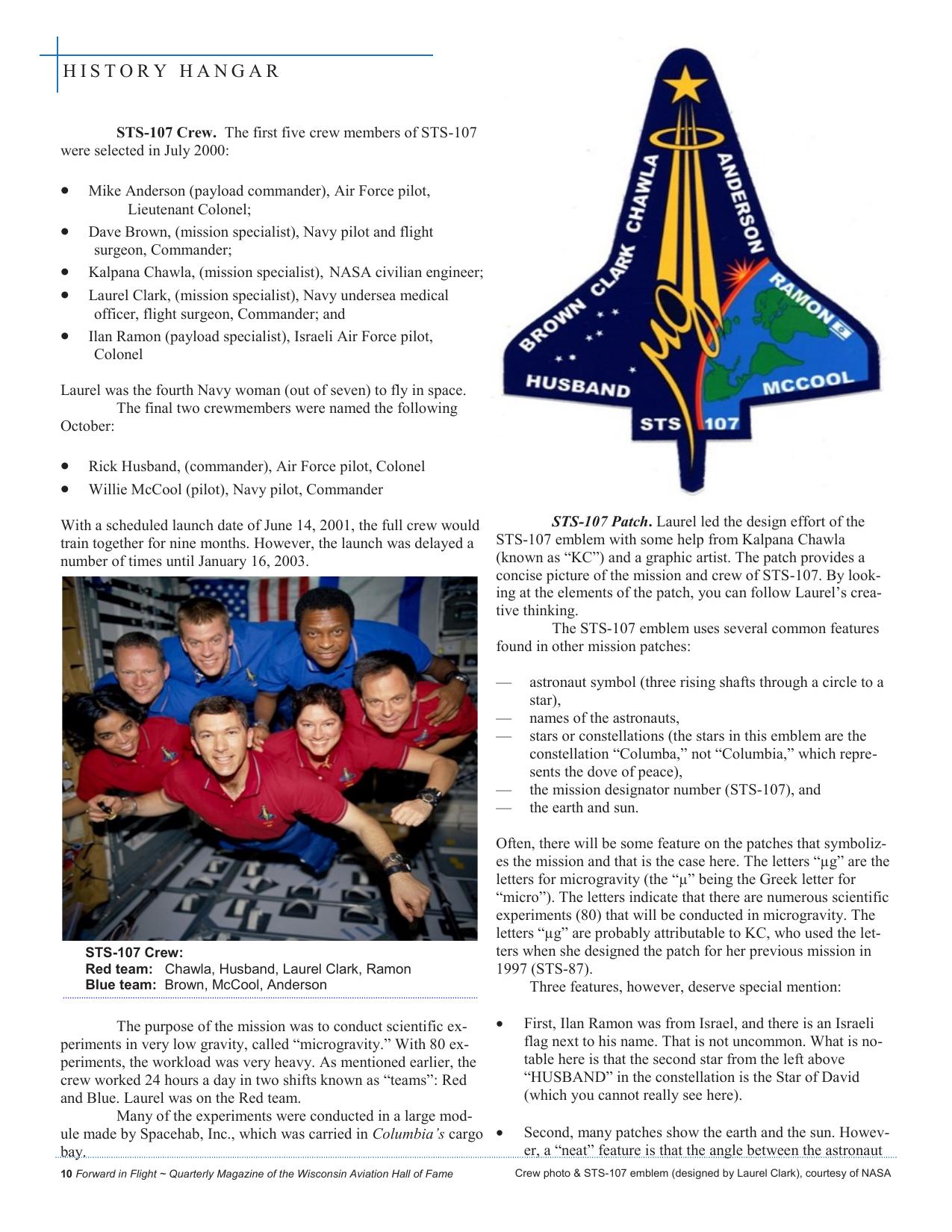

HISTORY HANGAR STS-107 Crew. The first five crew members of STS-107 were selected in July 2000: • • • • • Mike Anderson (payload commander), Air Force pilot, Lieutenant Colonel; Dave Brown, (mission specialist), Navy pilot and flight surgeon, Commander; Kalpana Chawla, (mission specialist), NASA civilian engineer; Laurel Clark, (mission specialist), Navy undersea medical officer, flight surgeon, Commander; and Ilan Ramon (payload specialist), Israeli Air Force pilot, Colonel Laurel was the fourth Navy woman (out of seven) to fly in space. The final two crewmembers were named the following October: • • Rick Husband, (commander), Air Force pilot, Colonel Willie McCool (pilot), Navy pilot, Commander With a scheduled launch date of June 14, 2001, the full crew would train together for nine months. However, the launch was delayed a number of times until January 16, 2003. STS-107 Patch. Laurel led the design effort of the STS-107 emblem with some help from Kalpana Chawla (known as “KC”) and a graphic artist. The patch provides a concise picture of the mission and crew of STS-107. By looking at the elements of the patch, you can follow Laurel’s creative thinking. The STS-107 emblem uses several common features found in other mission patches: — — — — — STS-107 Crew: Red team: Chawla, Husband, Laurel Clark, Ramon Blue team: Brown, McCool, Anderson Often, there will be some feature on the patches that symbolizes the mission and that is the case here. The letters “µg” are the letters for microgravity (the “µ” being the Greek letter for “micro”). The letters indicate that there are numerous scientific experiments (80) that will be conducted in microgravity. The letters “µg” are probably attributable to KC, who used the letters when she designed the patch for her previous mission in 1997 (STS-87). Three features, however, deserve special mention: • The purpose of the mission was to conduct scientific experiments in very low gravity, called “microgravity.” With 80 experiments, the workload was very heavy. As mentioned earlier, the crew worked 24 hours a day in two shifts known as “teams”: Red and Blue. Laurel was on the Red team. Many of the experiments were conducted in a large module made by Spacehab, Inc., which was carried in Columbia’s cargo • bay. 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame astronaut symbol (three rising shafts through a circle to a star), names of the astronauts, stars or constellations (the stars in this emblem are the constellation “Columba,” not “Columbia,” which represents the dove of peace), the mission designator number (STS-107), and the earth and sun. First, Ilan Ramon was from Israel, and there is an Israeli flag next to his name. That is not uncommon. What is notable here is that the second star from the left above “HUSBAND” in the constellation is the Star of David (which you cannot really see here). Second, many patches show the earth and the sun. However, a “neat” feature is that the angle between the astronaut Crew photo & STS-107 emblem (designed by Laurel Clark), courtesy of NASA

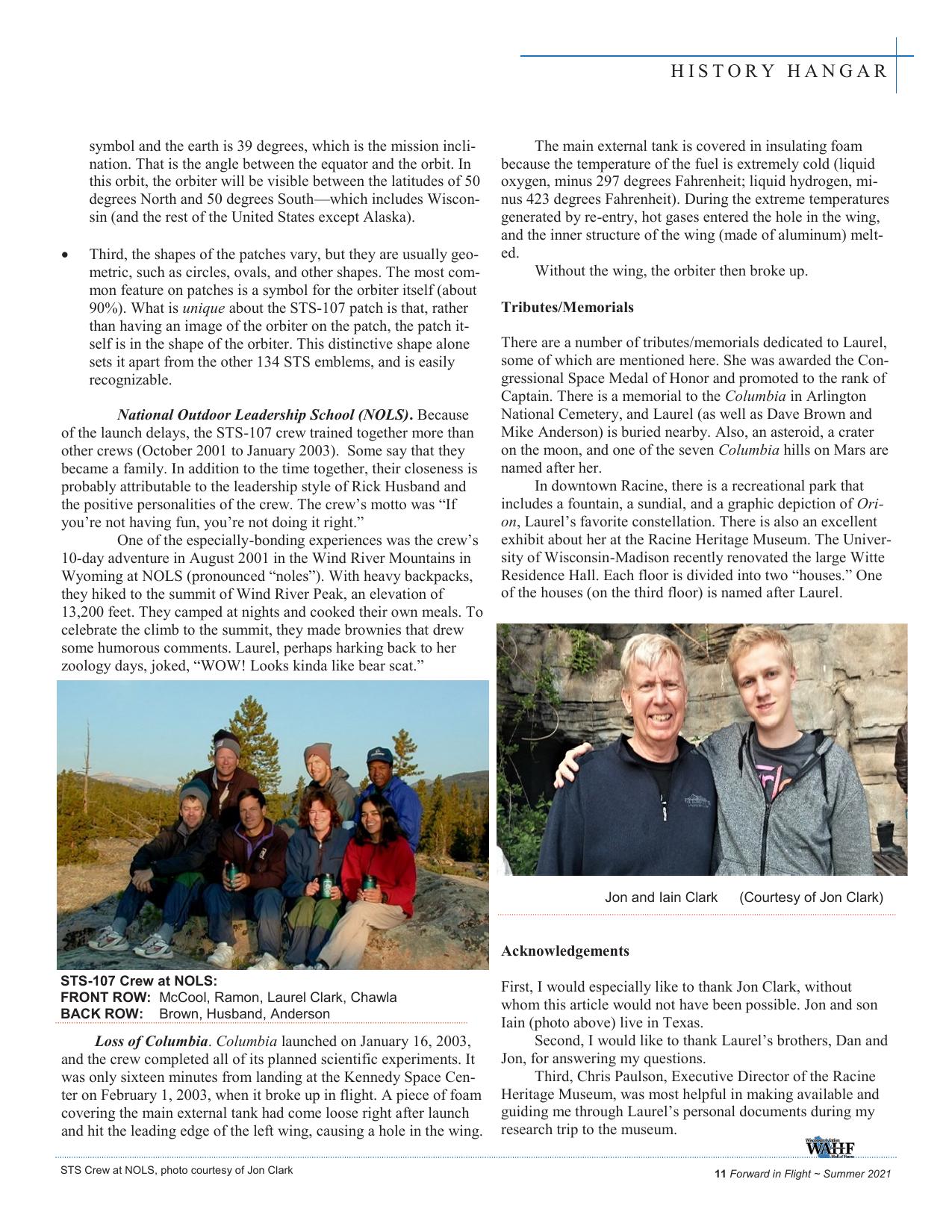

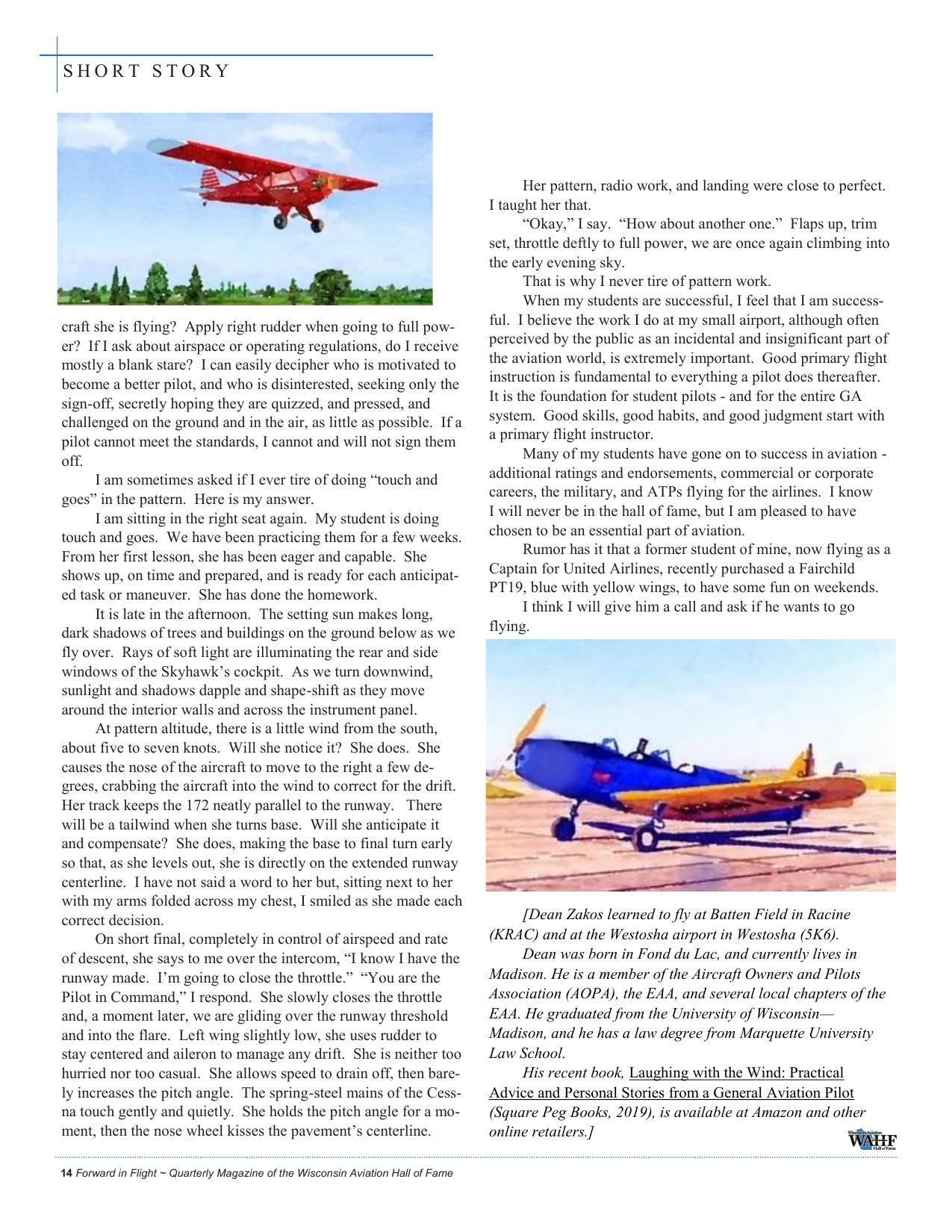

HISTORY HANGAR symbol and the earth is 39 degrees, which is the mission inclination. That is the angle between the equator and the orbit. In this orbit, the orbiter will be visible between the latitudes of 50 degrees North and 50 degrees South—which includes Wisconsin (and the rest of the United States except Alaska). • Third, the shapes of the patches vary, but they are usually geometric, such as circles, ovals, and other shapes. The most common feature on patches is a symbol for the orbiter itself (about 90%). What is unique about the STS-107 patch is that, rather than having an image of the orbiter on the patch, the patch itself is in the shape of the orbiter. This distinctive shape alone sets it apart from the other 134 STS emblems, and is easily recognizable. National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS). Because of the launch delays, the STS-107 crew trained together more than other crews (October 2001 to January 2003). Some say that they became a family. In addition to the time together, their closeness is probably attributable to the leadership style of Rick Husband and the positive personalities of the crew. The crew’s motto was “If you’re not having fun, you’re not doing it right.” One of the especially-bonding experiences was the crew’s 10-day adventure in August 2001 in the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming at NOLS (pronounced “noles”). With heavy backpacks, they hiked to the summit of Wind River Peak, an elevation of 13,200 feet. They camped at nights and cooked their own meals. To celebrate the climb to the summit, they made brownies that drew some humorous comments. Laurel, perhaps harking back to her zoology days, joked, “WOW! Looks kinda like bear scat.” The main external tank is covered in insulating foam because the temperature of the fuel is extremely cold (liquid oxygen, minus 297 degrees Fahrenheit; liquid hydrogen, minus 423 degrees Fahrenheit). During the extreme temperatures generated by re-entry, hot gases entered the hole in the wing, and the inner structure of the wing (made of aluminum) melted. Without the wing, the orbiter then broke up. Tributes/Memorials There are a number of tributes/memorials dedicated to Laurel, some of which are mentioned here. She was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor and promoted to the rank of Captain. There is a memorial to the Columbia in Arlington National Cemetery, and Laurel (as well as Dave Brown and Mike Anderson) is buried nearby. Also, an asteroid, a crater on the moon, and one of the seven Columbia hills on Mars are named after her. In downtown Racine, there is a recreational park that includes a fountain, a sundial, and a graphic depiction of Orion, Laurel’s favorite constellation. There is also an excellent exhibit about her at the Racine Heritage Museum. The University of Wisconsin-Madison recently renovated the large Witte Residence Hall. Each floor is divided into two “houses.” One of the houses (on the third floor) is named after Laurel. Jon and Iain Clark (Courtesy of Jon Clark) Acknowledgements STS-107 Crew at NOLS: FRONT ROW: McCool, Ramon, Laurel Clark, Chawla BACK ROW: Brown, Husband, Anderson Loss of Columbia. Columbia launched on January 16, 2003, and the crew completed all of its planned scientific experiments. It was only sixteen minutes from landing at the Kennedy Space Center on February 1, 2003, when it broke up in flight. A piece of foam covering the main external tank had come loose right after launch and hit the leading edge of the left wing, causing a hole in the wing. STS Crew at NOLS, photo courtesy of Jon Clark First, I would especially like to thank Jon Clark, without whom this article would not have been possible. Jon and son Iain (photo above) live in Texas. Second, I would like to thank Laurel’s brothers, Dan and Jon, for answering my questions. Third, Chris Paulson, Executive Director of the Racine Heritage Museum, was most helpful in making available and guiding me through Laurel’s personal documents during my research trip to the museum. 11 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2021

SHORT STORY Who is the Teacher? For Pete, who loves to fly By Dean Zakos “When one teaches, two learn.” – Robert Heinlein I am sitting, perhaps a little too casually, in the right seat of a Cessna 172 Skyhawk. In the left seat is a young man about to attempt a power-on stall. We are in the practice area, with the airport we departed from on the distant horizon. After two ninety-degree clearing turns, we remain at 2,000 feet above ground level, with just a few scattered clouds above us on a beautiful, late spring day. I have talked through the procedure numerous times and have demonstrated the maneuver for him just a moment ago. Now, it is his turn. He reduces the throttle to 1500 RPM. Holding altitude, the airspeed needle approaches 70 knots. I ask him to go to full power, remind him to use some right rudder to maintain heading, and pitch the nose up. The stall warning horn comes on. We see only clouds and sky above the instrument panel. “Keep pulling back,” I advise. There is a buffet, then the stall breaks and the nose slices down through the horizon. The left wing dips. Suddenly, it drops out of sight and we wing over into a spin. I did not catch it in time. Loose objects float through the air. The earth, a patchwork of fields, small ponds, and country roads, now fills the windshield – and it is rotating. Did he apply right aileron hoping to pick up the left wing? Did he inadvertently put pressure on left rudder? Using my eyes, I was following through with him on the controls. What did I miss? No time to think about that now. “My airplane,” I say calmly. “Your airplane,” he blurts out excitedly as he relinquishes the controls. Quickly pulling the power to idle, I return the ailerons to neutral, touch the right rudder pedal to counteract the direction of the spin, and then push forward on the yoke. Once flying speed is regained, I begin to raise the nose of the Skyhawk back to level flight and advance the throttle. We did about a spin and a half before recovering. This does not happen often to me but, over the years, it has happened once or twice before. “Let’s try that stall and recovery again,” I say reassuringly to my student. I am a certified flight instructor. I am not “building time.” I am not planning on an eventual airline career. I simply want to teach people to fly. I have always wanted to do that. I gladly would do it full time if I could, but I need a job that pays (with benefits) to make life financially stable for me. So, during the week I am gainfully employed elsewhere, but that vocation allows me to sit in an airplane and instruct on weekends and some evenings. You can guess which job I enjoy more. I have been told it shows. I have shared with a few close friends that when I started out instructing many years ago, I should have paid my first five students instead of them paying me. I learned that much – and I am still learning with every flight. 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame I was interested in flight almost from the beginning of my life, starting with small gliders made out of styrofoam or balsa wood purchased for me by my grandfather at the local Ben Franklin store. When I was eight years old, I had a paper route that allowed me to make a little money. Naturally, when I saved up enough, I brought home from the hobby shop a linecontrolled, gas powered Fairchild PT19 model with a blue fuselage and yellow wings. Over long summer days, I spun myself dizzy as the small, low-wing aircraft, colorful and noisy against the clear sky, made tethered circles around me in a vacant field. I always imagined that it was me inside the cockpit at the controls of that PT19. Someday, I thought. As a sophomore in college, a complete stranger in one of my classes approached me and asked if I would like to go flying. That was my first flight in a small plane. The college offered a flight training program, and I signed up as soon as I could. In fact, I signed up for every aviation class offered. I trained in a Piper Warrior. Received my PPL in 1980. In 1982, I ran into a health issue and could not renew my Third Class medical certificate. I bought a kit and built a Rotec Rally 2B+ ultralight, happily operating my “flying lawn chair” to satisfy my aviation fix. In 1990, I obtained my glider rating, flying a Blanik L13. I also added a commercial glider certificate in a Blanik L23. Gliders provided the bridge I needed to continue to fly until my medical could get sorted out. In 1997, I was able to obtain a Third Class Special Issuance medical. The grounding of all VFR aircraft after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack in New York gave me the incentive to train for my instrument rating. That was in 2002. Two years later, I received my commercial ticket, and two years after that, my instructor certificate. I think, in many ways, I have managed to have it all. My day job affords me a living, and my instructing job not only makes flying financially possible, but it puts a little money in my pocket. I am living the dream whenever I am flying. Back on the ramp, I talk with my student about the tasks just completed and the series of stalls and recoveries we worked on. We debrief the just-concluded flight, particularly the stall/ spin (he did mistakenly jab the left rudder at the stall break), the aerodynamics of the stall becoming a spin, and ways the student can improve performance for the next lesson. The student asks good questions and, despite the unplanned excitement, is engaged and looking forward to going up again. Flight instructors, over time, should become skilled at reading people, particularly their own students. Not everyone learns in the same way. In addition to understanding the FAA regulations, and having the necessary flying skills, a high emotional IQ is a definite plus when teaching someone to fly. What Copyright © 2021 Dean Zakos. All rights reserved.

SHORT STORY is the personality of my student? How will the student best learn the concepts I must ensure they understand? What motivates him or her? What concerns does he or she have? What do I need to do to see that success is achieved? I suppose it is similar to being a coach of an athletic team. I have to be perceptive enough to know when someone is on their game or when they are not at their best. I need to give encouragement when deserved and constructive criticism when warranted. I have taught many students from different walks of life. Although no two students are alike, I can venture to make some generalizations. Engineers easily “get” the aerodynamics of flight, but sometimes drive me crazy because they are so precise. Where a short answer suffices with most students, engineers want all the details. Dentists are also detail-oriented, as are lawyers. Doctors and CEOs have been some of my worst students. Not all. It is a mixed bag. There are those who have college or professional degrees or have attained status in the business world and, sometimes, they want to tell me how to fly. A few want only to meet minimum standards, and quickly, so they can add the private pilot license to their impressive list of accomplishments. Young people, especially teenagers, can be the easiest to teach. Whether someone is a plumber or a PhD, if they bring passion and commitment, I can teach them to fly. Aggressiveness and overconfidence are simple to spot in a student and, often, are correctable. It can be much more difficult for an instructor to recognize fear. A student may be adept, for a while at least, at hiding his or her fear. It can masquerade as a reluctance, or a deferral, or conceal itself behind a false projection of bravado. Often it only makes itself known in the moment -- as I step out of the airplane after informing the student he or she is ready to do some take-offs and landings without me sitting at their side; or when performing a stall, when the nose drops, and the student, instead of reacting, curls up into a fetal position in the left seat; or when a student freezes in the landing flare, unresponsive and staring out into space, as we are rapidly losing airspeed and eating up runway eight feet in the air. I have lost some good pilot friends to accidents over the years. If you fly, you probably have lost some friends too. The statistics, trending over time, show that general aviation pilots are as safe or safer now than they have ever been. However, there will always be risk in flight. It can never be completely eliminated. It can be mitigated but, if a pilot makes a serious mistake, the result can be unforgiving and tragic. I tell my students exactly that. Risk will not deter me from fulfilling my dream and doing what I love. I do not pretend to understand life’s mysteries or the cruel reality of random chance. I can only control what I can control. I must put my faith and trust in my own knowledge, my flying skills and experience, and the airplane I fly, come what may. I think the first few lessons are the most critical for my students. Understanding and learning maneuvers – climbs, turns, straight and level, and descents – set them up with the fundamentals they need for everything that comes after. I prefer to teach in a tailwheel aircraft or a high-wing aircraft, as it makes it easier for the student to see things like adverse yaw in an uncoordinated turn. Do not get me wrong, I like flying lowwing aircraft. But give me a Piper J-3 Cub or an Aeronca Chief, or a Cessna 152 or 172, for primary instruction. It is the middle of a Saturday for me, a day that started with my first lesson at 8:00 am and continuing with the current lesson, having commenced at 10:00 am, just concluding now. I am going to grab a bite to eat, and then prepare for the next appointment in the book at 2:30 pm. My wife, who is understanding and supportive of what I do, will meet me at the FBO with a brown bag lunch she prepared. Later in the day, I am scheduled for a Flight Review with a pilot in his beautifully restored Cub flying off a nearby grass strip. If you instruct, you know. There is ample downtime in many flight instructors’ schedules. Equipment failures, 100 hour inspections, weather, scheduling conflicts, and no shows are, if not a constant, at least a normal part of teaching student pilots in the general aviation world. I enjoy endorsing my students’ logbooks for their checkrides. My pleasure comes from my confidence in, and expectation that, my students will do well. I let them know that the DPE is not going to be looking for ways to fail them, but for ways to pass them. A DPE should, within the limits of the Airman Certification Standards, want the student to succeed. I certainly do. When one of my students passes the checkride, I want to be able to say to myself, and to know in my heart, that I did all I possibly could to provide that new pilot with everything he or she needs to fly safely and competently. I am asked to do quite a few Flight Reviews. Tricycle gear, tail-draggers, complex, low-wing, high-wing, experimentals, antiques, classics – I have experience in all of them. Generally, I can tell by the time we start rolling down the runway if a pilot is proficient and he or she will meet the standards. Does he use checklists? Does she understand the systems in the air13 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2021

SHORT STORY craft she is flying? Apply right rudder when going to full power? If I ask about airspace or operating regulations, do I receive mostly a blank stare? I can easily decipher who is motivated to become a better pilot, and who is disinterested, seeking only the sign-off, secretly hoping they are quizzed, and pressed, and challenged on the ground and in the air, as little as possible. If a pilot cannot meet the standards, I cannot and will not sign them off. I am sometimes asked if I ever tire of doing “touch and goes” in the pattern. Here is my answer. I am sitting in the right seat again. My student is doing touch and goes. We have been practicing them for a few weeks. From her first lesson, she has been eager and capable. She shows up, on time and prepared, and is ready for each anticipated task or maneuver. She has done the homework. It is late in the afternoon. The setting sun makes long, dark shadows of trees and buildings on the ground below as we fly over. Rays of soft light are illuminating the rear and side windows of the Skyhawk’s cockpit. As we turn downwind, sunlight and shadows dapple and shape-shift as they move around the interior walls and across the instrument panel. At pattern altitude, there is a little wind from the south, about five to seven knots. Will she notice it? She does. She causes the nose of the aircraft to move to the right a few degrees, crabbing the aircraft into the wind to correct for the drift. Her track keeps the 172 neatly parallel to the runway. There will be a tailwind when she turns base. Will she anticipate it and compensate? She does, making the base to final turn early so that, as she levels out, she is directly on the extended runway centerline. I have not said a word to her but, sitting next to her with my arms folded across my chest, I smiled as she made each correct decision. On short final, completely in control of airspeed and rate of descent, she says to me over the intercom, “I know I have the runway made. I’m going to close the throttle.” “You are the Pilot in Command,” I respond. She slowly closes the throttle and, a moment later, we are gliding over the runway threshold and into the flare. Left wing slightly low, she uses rudder to stay centered and aileron to manage any drift. She is neither too hurried nor too casual. She allows speed to drain off, then barely increases the pitch angle. The spring-steel mains of the Cessna touch gently and quietly. She holds the pitch angle for a moment, then the nose wheel kisses the pavement’s centerline. 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Her pattern, radio work, and landing were close to perfect. I taught her that. “Okay,” I say. “How about another one.” Flaps up, trim set, throttle deftly to full power, we are once again climbing into the early evening sky. That is why I never tire of pattern work. When my students are successful, I feel that I am successful. I believe the work I do at my small airport, although often perceived by the public as an incidental and insignificant part of the aviation world, is extremely important. Good primary flight instruction is fundamental to everything a pilot does thereafter. It is the foundation for student pilots - and for the entire GA system. Good skills, good habits, and good judgment start with a primary flight instructor. Many of my students have gone on to success in aviation additional ratings and endorsements, commercial or corporate careers, the military, and ATPs flying for the airlines. I know I will never be in the hall of fame, but I am pleased to have chosen to be an essential part of aviation. Rumor has it that a former student of mine, now flying as a Captain for United Airlines, recently purchased a Fairchild PT19, blue with yellow wings, to have some fun on weekends. I think I will give him a call and ask if he wants to go flying. [Dean Zakos learned to fly at Batten Field in Racine (KRAC) and at the Westosha airport in Westosha (5K6). Dean was born in Fond du Lac, and currently lives in Madison. He is a member of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), the EAA, and several local chapters of the EAA. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin— Madison, and he has a law degree from Marquette University Law School. His recent book, Laughing with the Wind: Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot (Square Peg Books, 2019), is available at Amazon and other online retailers.]

2020 & 2021 WAHF INDUCTEES Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony For the 2020 and 2021 Classes of Inductees 2020: Robert Brackett, John Moody, Tad Oelstrom, and Sherwood Williams 2021: William Blank, Don Kiel, and Daniel Knutson By Tom Thomas The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame, Inc. (WAHF) is the result of an idea by Carl Guell. While employed by the Wisconsin Aeronautics Commission (now the Department of Transportation, Bureau of Aeronautics), Guell began collecting the state's aviation history. Encouraged by the wealth of information that he discovered through interviews and research, Guell incorporated the WAHF in 1985. The organization inducted its first class of three Wisconsin aviation notables less than a year later. Since then, 145 individuals have been honored for their tremendous contribution to Wisconsin aviation history. Last year, WAHF announced that four more individual aviators would be inducted into WAHF: Robert Brackett, John Moody, Tad Oelstrom, and Sherwood Williams. The Induction ceremony was scheduled to take place in October, 2020. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, however, WAHF had to cancel that Induction Ceremony. This year, then, a joint Induction Ceremony will be held for the 2021 Class of inductees and for the 2020 Class as well. President Tom Thomas, on behalf of the WAHF Board of Directors, is proud to announce the following individuals as this year’s class of inductees: William Blank, Don Kiel, and Daniel Knutson. Please join us in celebrating the 2020 and 2021 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame inductees during our 35th induction event on Saturday, October 23, 2021, in the Experimental Aircraft Association Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The evening begins with a social hour at 5:00 PM, dinner at 6:00 PM, with our ceremony to follow. Additional information on the ceremony, membership, and past inductees can be found at www.wisconsinaviationhalloffame.org. Join today and help us to preserve our state’s aviation history and to honor those who are creating it! To learn more information on the four Inductees for 2020, please refer to the Summer 2020 issue (pages 16-17). Robert Brackett Brackett photo courtesy of S. Brackett; Moody photo courtesy of EAA (T. Bogenhagen) John Moody 15 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2021

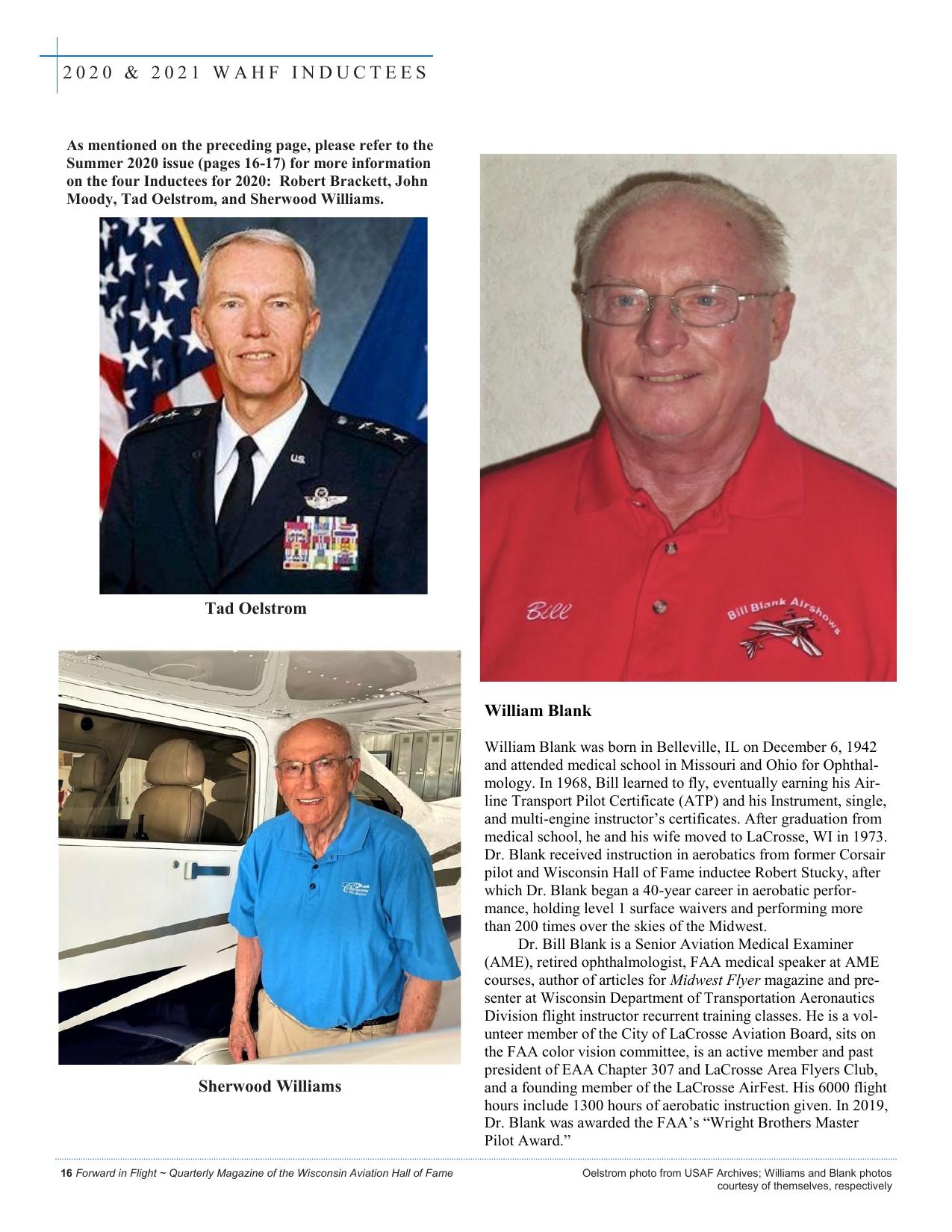

2020 & 2021 WAHF INDUCTEES As mentioned on the preceding page, please refer to the Summer 2020 issue (pages 16-17) for more information on the four Inductees for 2020: Robert Brackett, John Moody, Tad Oelstrom, and Sherwood Williams. Tad Oelstrom William Blank Sherwood Williams 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame William Blank was born in Belleville, IL on December 6, 1942 and attended medical school in Missouri and Ohio for Ophthalmology. In 1968, Bill learned to fly, eventually earning his Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP) and his Instrument, single, and multi-engine instructor’s certificates. After graduation from medical school, he and his wife moved to LaCrosse, WI in 1973. Dr. Blank received instruction in aerobatics from former Corsair pilot and Wisconsin Hall of Fame inductee Robert Stucky, after which Dr. Blank began a 40-year career in aerobatic performance, holding level 1 surface waivers and performing more than 200 times over the skies of the Midwest. Dr. Bill Blank is a Senior Aviation Medical Examiner (AME), retired ophthalmologist, FAA medical speaker at AME courses, author of articles for Midwest Flyer magazine and presenter at Wisconsin Department of Transportation Aeronautics Division flight instructor recurrent training classes. He is a volunteer member of the City of LaCrosse Aviation Board, sits on the FAA color vision committee, is an active member and past president of EAA Chapter 307 and LaCrosse Area Flyers Club, and a founding member of the LaCrosse AirFest. His 6000 flight hours include 1300 hours of aerobatic instruction given. In 2019, Dr. Blank was awarded the FAA’s “Wright Brothers Master Pilot Award.” Oelstrom photo from USAF Archives; Williams and Blank photos courtesy of themselves, respectively

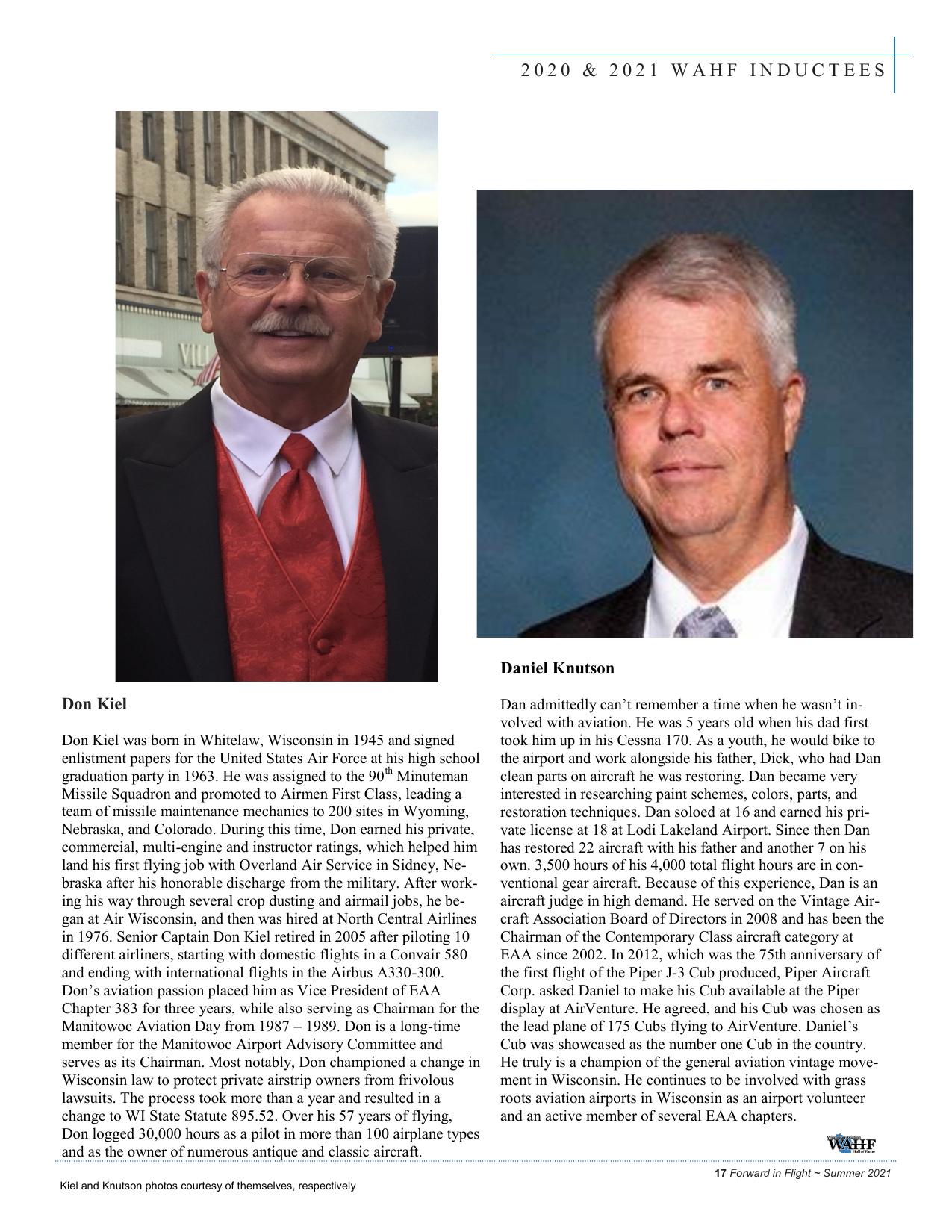

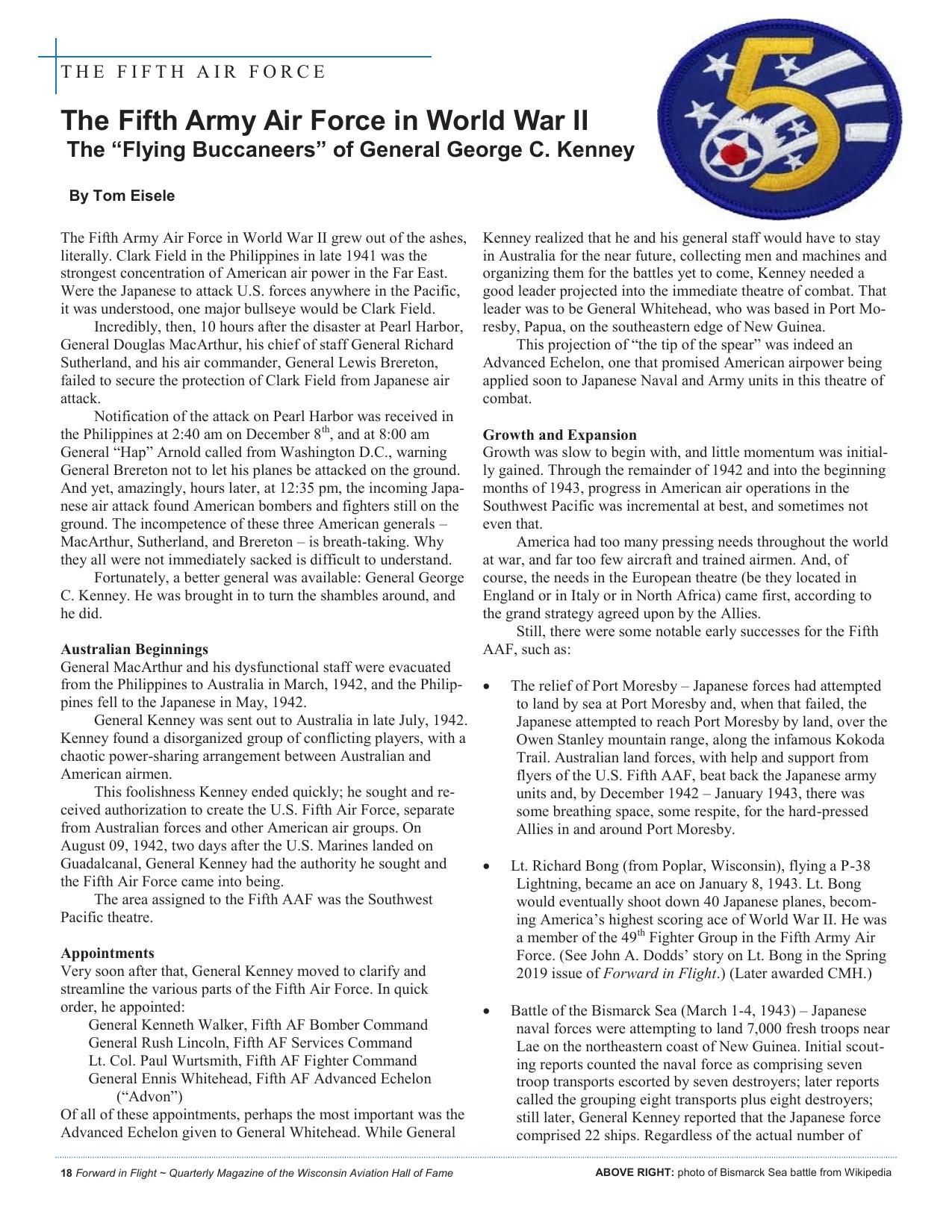

2020 & 2021 WAHF INDUCTEES Daniel Knutson Don Kiel Don Kiel was born in Whitelaw, Wisconsin in 1945 and signed enlistment papers for the United States Air Force at his high school graduation party in 1963. He was assigned to the 90 th Minuteman Missile Squadron and promoted to Airmen First Class, leading a team of missile maintenance mechanics to 200 sites in Wyoming, Nebraska, and Colorado. During this time, Don earned his private, commercial, multi-engine and instructor ratings, which helped him land his first flying job with Overland Air Service in Sidney, Nebraska after his honorable discharge from the military. After working his way through several crop dusting and airmail jobs, he began at Air Wisconsin, and then was hired at North Central Airlines in 1976. Senior Captain Don Kiel retired in 2005 after piloting 10 different airliners, starting with domestic flights in a Convair 580 and ending with international flights in the Airbus A330-300. Don’s aviation passion placed him as Vice President of EAA Chapter 383 for three years, while also serving as Chairman for the Manitowoc Aviation Day from 1987 – 1989. Don is a long-time member for the Manitowoc Airport Advisory Committee and serves as its Chairman. Most notably, Don championed a change in Wisconsin law to protect private airstrip owners from frivolous lawsuits. The process took more than a year and resulted in a change to WI State Statute 895.52. Over his 57 years of flying, Don logged 30,000 hours as a pilot in more than 100 airplane types and as the owner of numerous antique and classic aircraft. Dan admittedly can’t remember a time when he wasn’t involved with aviation. He was 5 years old when his dad first took him up in his Cessna 170. As a youth, he would bike to the airport and work alongside his father, Dick, who had Dan clean parts on aircraft he was restoring. Dan became very interested in researching paint schemes, colors, parts, and restoration techniques. Dan soloed at 16 and earned his private license at 18 at Lodi Lakeland Airport. Since then Dan has restored 22 aircraft with his father and another 7 on his own. 3,500 hours of his 4,000 total flight hours are in conventional gear aircraft. Because of this experience, Dan is an aircraft judge in high demand. He served on the Vintage Aircraft Association Board of Directors in 2008 and has been the Chairman of the Contemporary Class aircraft category at EAA since 2002. In 2012, which was the 75th anniversary of the first flight of the Piper J-3 Cub produced, Piper Aircraft Corp. asked Daniel to make his Cub available at the Piper display at AirVenture. He agreed, and his Cub was chosen as the lead plane of 175 Cubs flying to AirVenture. Daniel’s Cub was showcased as the number one Cub in the country. He truly is a champion of the general aviation vintage movement in Wisconsin. He continues to be involved with grass roots aviation airports in Wisconsin as an airport volunteer and an active member of several EAA chapters. 17 Forward in Flight ~ Summer 2021 Kiel and Knutson photos courtesy of themselves, respectively

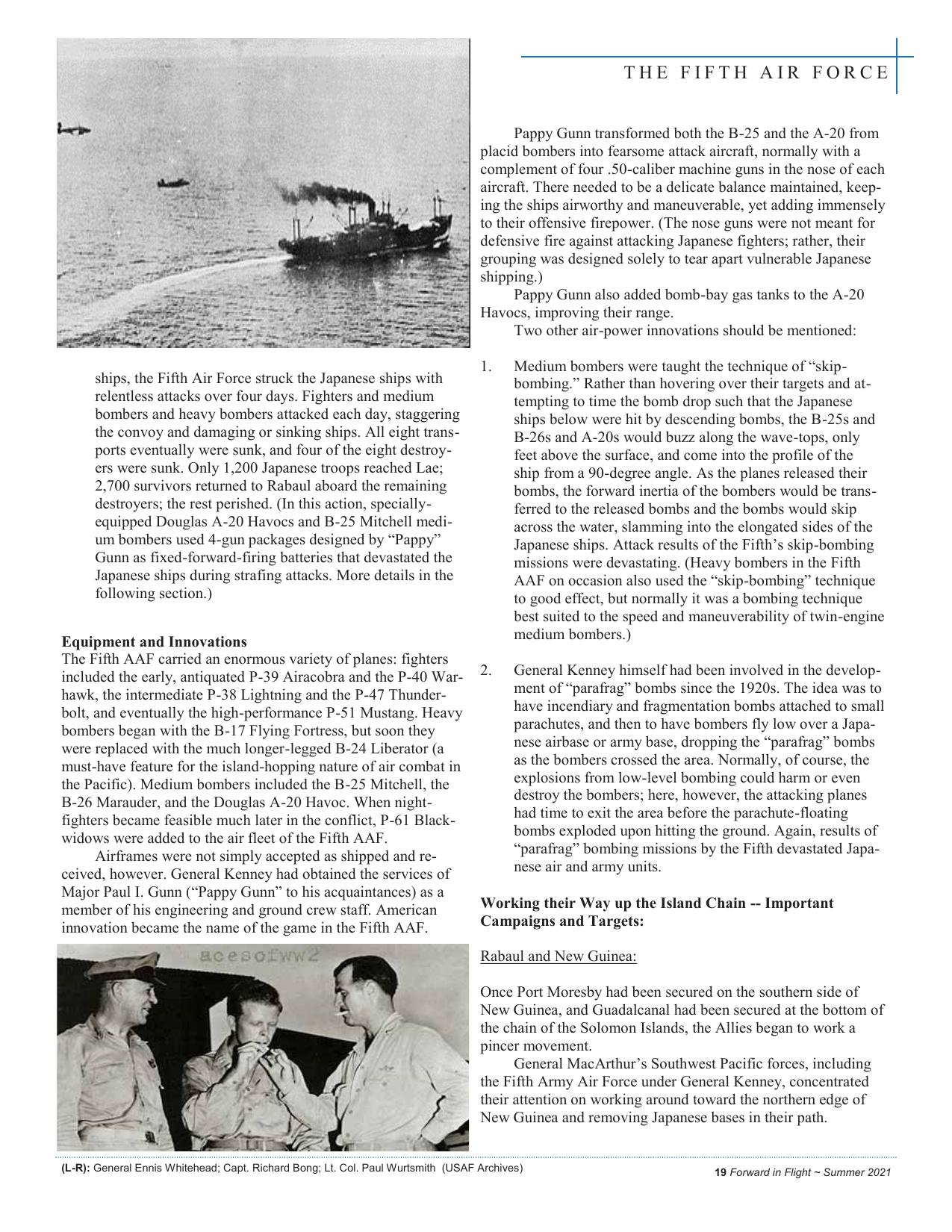

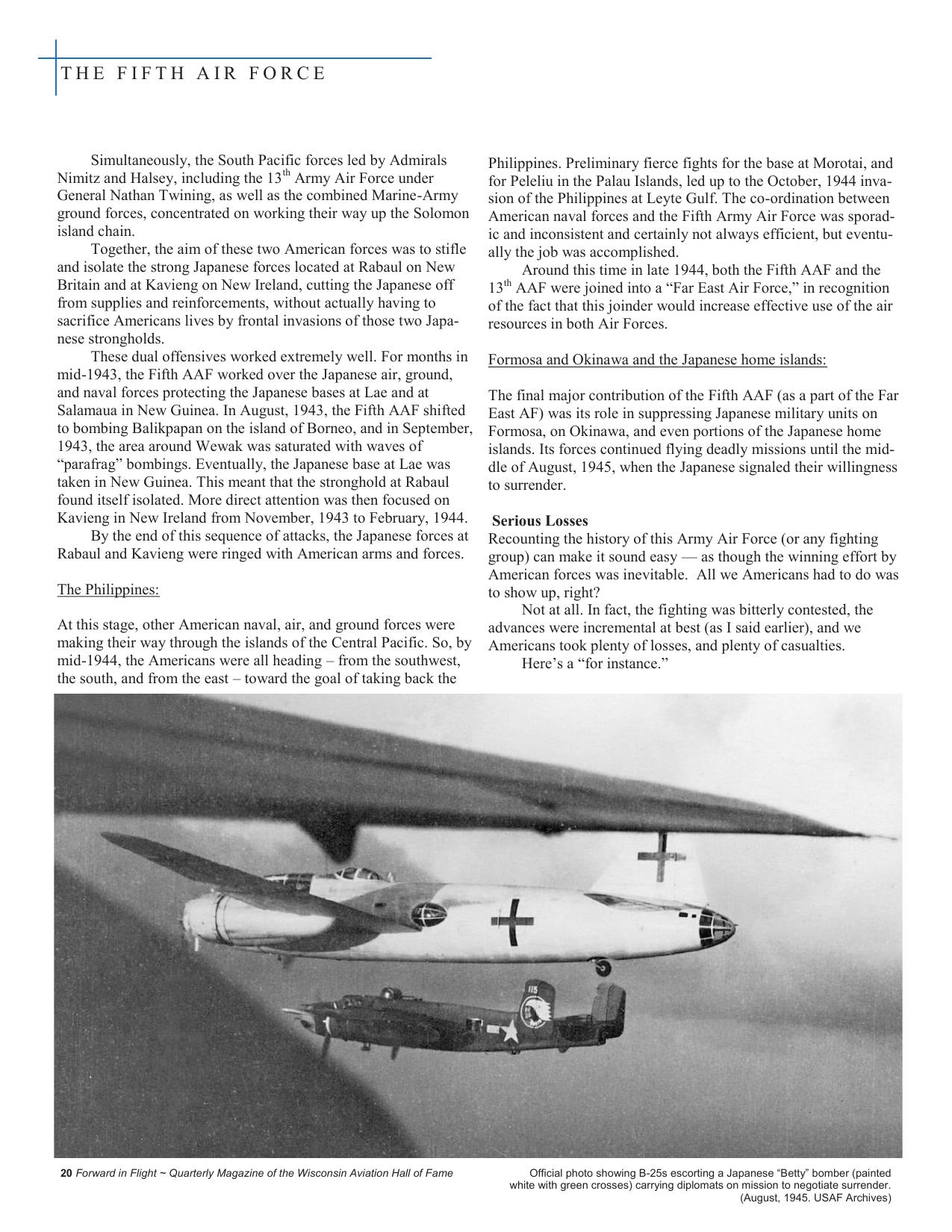

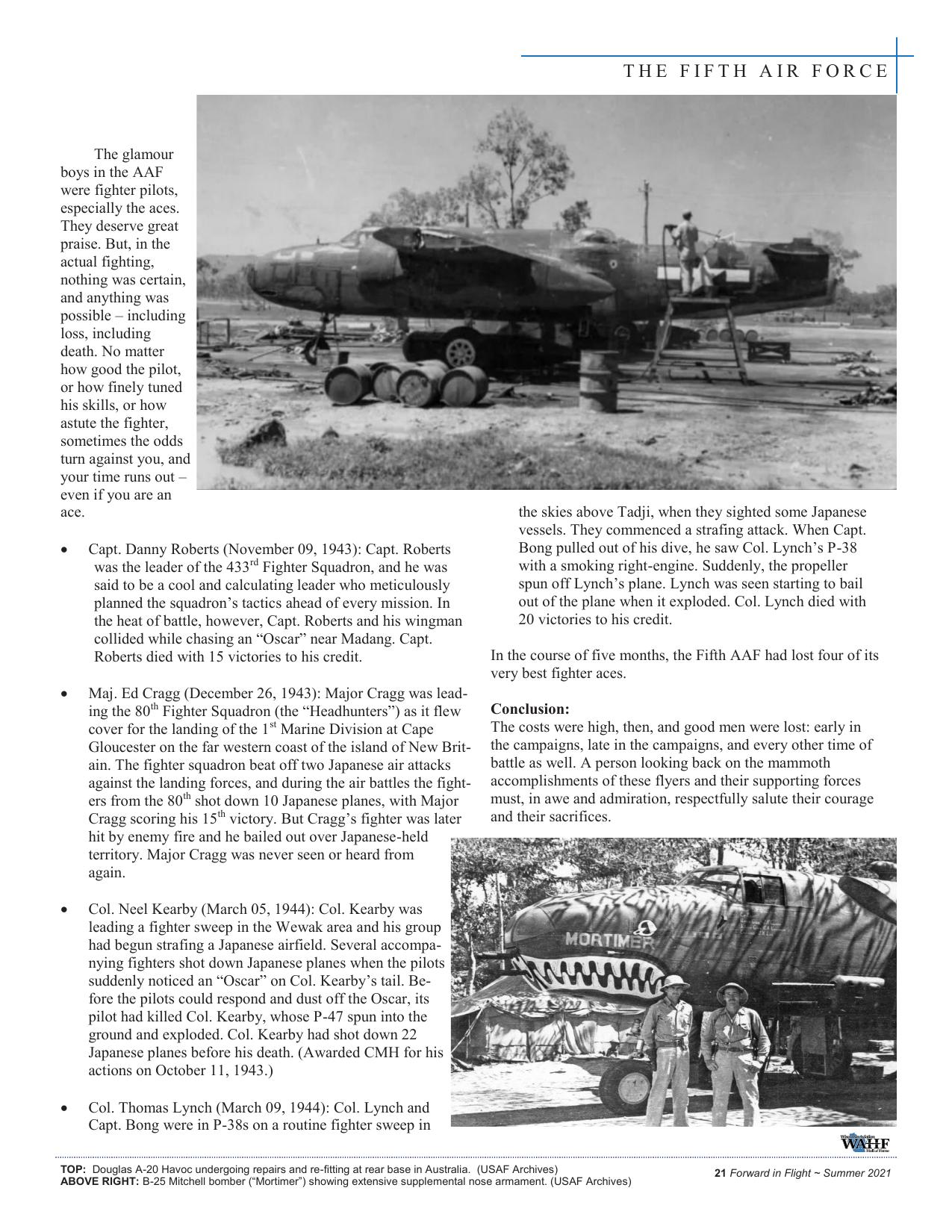

THE FIFTH AIR FORCE The Fifth Army Air Force in World War II The “Flying Buccaneers” of General George C. Kenney By Tom Eisele The Fifth Army Air Force in World War II grew out of the ashes, literally. Clark Field in the Philippines in late 1941 was the strongest concentration of American air power in the Far East. Were the Japanese to attack U.S. forces anywhere in the Pacific, it was understood, one major bullseye would be Clark Field. Incredibly, then, 10 hours after the disaster at Pearl Harbor, General Douglas MacArthur, his chief of staff General Richard Sutherland, and his air commander, General Lewis Brereton, failed to secure the protection of Clark Field from Japanese air attack. Notification of the attack on Pearl Harbor was received in the Philippines at 2:40 am on December 8 th, and at 8:00 am General “Hap” Arnold called from Washington D.C., warning General Brereton not to let his planes be attacked on the ground. And yet, amazingly, hours later, at 12:35 pm, the incoming Japanese air attack found American bombers and fighters still on the ground. The incompetence of these three American generals – MacArthur, Sutherland, and Brereton – is breath-taking. Why they all were not immediately sacked is difficult to understand. Fortunately, a better general was available: General George C. Kenney. He was brought in to turn the shambles around, and he did. Kenney realized that he and his general staff would have to stay in Australia for the near future, collecting men and machines and organizing them for the battles yet to come, Kenney needed a good leader projected into the immediate theatre of combat. That leader was to be General Whitehead, who was based in Port Moresby, Papua, on the southeastern edge of New Guinea. This projection of “the tip of the spear” was indeed an Advanced Echelon, one that promised American airpower being applied soon to Japanese Naval and Army units in this theatre of combat. Growth and Expansion Growth was slow to begin with, and little momentum was initially gained. Through the remainder of 1942 and into the beginning months of 1943, progress in American air operations in the Southwest Pacific was incremental at best, and sometimes not even that. America had too many pressing needs throughout the world at war, and far too few aircraft and trained airmen. And, of course, the needs in the European theatre (be they located in England or in Italy or in North Africa) came first, according to the grand strategy agreed upon by the Allies. Still, there were some notable early successes for the Fifth AAF, such as: Australian Beginnings General MacArthur and his dysfunctional staff were evacuated from the Philippines to Australia in March, 1942, and the Philip- • pines fell to the Japanese in May, 1942. General Kenney was sent out to Australia in late July, 1942. Kenney found a disorganized group of conflicting players, with a chaotic power-sharing arrangement between Australian and American airmen. This foolishness Kenney ended quickly; he sought and received authorization to create the U.S. Fifth Air Force, separate from Australian forces and other American air groups. On August 09, 1942, two days after the U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal, General Kenney had the authority he sought and • the Fifth Air Force came into being. The area assigned to the Fifth AAF was the Southwest Pacific theatre. Appointments Very soon after that, General Kenney moved to clarify and streamline the various parts of the Fifth Air Force. In quick order, he appointed: General Kenneth Walker, Fifth AF Bomber Command General Rush Lincoln, Fifth AF Services Command Lt. Col. Paul Wurtsmith, Fifth AF Fighter Command General Ennis Whitehead, Fifth AF Advanced Echelon (“Advon”) Of all of these appointments, perhaps the most important was the Advanced Echelon given to General Whitehead. While General 18 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame • The relief of Port Moresby – Japanese forces had attempted to land by sea at Port Moresby and, when that failed, the Japanese attempted to reach Port Moresby by land, over the Owen Stanley mountain range, along the infamous Kokoda Trail. Australian land forces, with help and support from flyers of the U.S. Fifth AAF, beat back the Japanese army units and, by December 1942 – January 1943, there was some breathing space, some respite, for the hard-pressed Allies in and around Port Moresby. Lt. Richard Bong (from Poplar, Wisconsin), flying a P-38 Lightning, became an ace on January 8, 1943. Lt. Bong would eventually shoot down 40 Japanese planes, becoming America’s highest scoring ace of World War II. He was a member of the 49th Fighter Group in the Fifth Army Air Force. (See John A. Dodds’ story on Lt. Bong in the Spring 2019 issue of Forward in Flight.) (Later awarded CMH.) Battle of the Bismarck Sea (March 1-4, 1943) – Japanese naval forces were attempting to land 7,000 fresh troops near Lae on the northeastern coast of New Guinea. Initial scouting reports counted the naval force as comprising seven troop transports escorted by seven destroyers; later reports called the grouping eight transports plus eight destroyers; still later, General Kenney reported that the Japanese force comprised 22 ships. Regardless of the actual number of ABOVE RIGHT: photo of Bismarck Sea battle from Wikipedia