Forward in Flight - Winter 2021

Volume 19, Issue 4 Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Winter 2021-2022

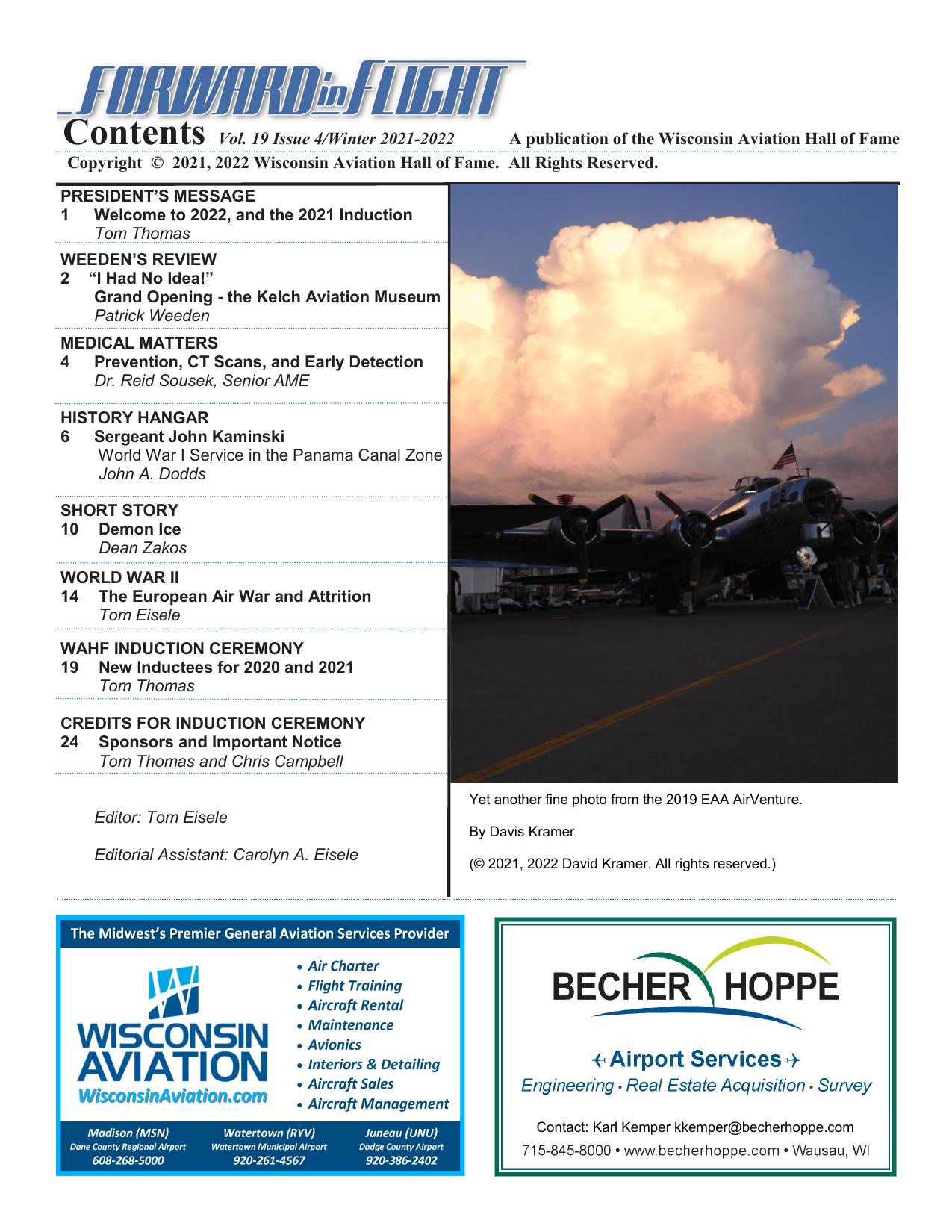

Contents Vol. 19 Issue 4/Winter 2021-2022 A publication of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Copyright © 2021, 2022 Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame. All Rights Reserved. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 1 Welcome to 2022, and the 2021 Induction Tom Thomas WEEDEN’S REVIEW 2 “I Had No Idea!” Grand Opening - the Kelch Aviation Museum Patrick Weeden MEDICAL MATTERS 4 Prevention, CT Scans, and Early Detection Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME HISTORY HANGAR 6 Sergeant John Kaminski World War I Service in the Panama Canal Zone John A. Dodds SHORT STORY 10 Demon Ice Dean Zakos WORLD WAR II 14 The European Air War and Attrition Tom Eisele WAHF INDUCTION CEREMONY 19 New Inductees for 2020 and 2021 Tom Thomas CREDITS FOR INDUCTION CEREMONY 24 Sponsors and Important Notice Tom Thomas and Chris Campbell Yet another fine photo from the 2019 EAA AirVenture. Editor: Tom Eisele Editorial Assistant: Carolyn A. Eisele By Davis Kramer (© 2021, 2022 David Kramer. All rights reserved.) Contact: Karl Kemper kkemper@becherhoppe.com

President’s Message By Tom Thomas Fall has arrived and winter is on the doorstep. October 23rd was a great evening to recognize both the 2020 and 2021 Inductees in EAA’s Eagle Hangar. Losing our 2020 Induction Ceremony to COVID-19, the decision was made to combine the two induction classes this year into one grand and memorable event. Normally, four individuals are inducted annually. Last year, four individuals were selected for induction, and then COVID came along. With the development of vaccines and the availability of shots, we were optimistic this year’s Induction Ceremony could work out. This year we selected three inductees, which were combined with the four 2020 inductees, giving us a total of seven. This year’s planning for the induction of seven welldeserving individuals incorporated a new, more efficient and informative method. The only other year that seven individuals were inducted was in 2000. That year, three of those seven were classified as aviation “pioneers.” Michael Goc, the author of The History of Aviation in Wisconsin, was serving on the WAHF Board at the time. Mike developed the “pioneer” classification to recognize individuals who’d accomplished significant aviation milestones prior to Lindberg crossing the Atlantic in May of 1927. When reviewing the listing of Inductees in our program, you’ll note that 40 “pioneer” inductees were selected between 2000 and 2013. The last of the aviation pioneers selected in 2013 was Governor Walter Kohler of Sheboygan. He was known as “The Flying Governor,” elected in 1928, having landed in 46 counties and logging 7,200 miles all across Wisconsin. This year’s ceremony will go down in history, tying the largest number of seven inductees in 2000. We’ve had higher attendance in past years, but this was only the second time in 34 years that we had seven inductees since the first individuals were inducted in 1986. It is interesting to note that for the first induction ceremony, the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame’s Board selected three inductees: General William (Billy) Mitchell, Paul Poberezny, and Steve Wittman. And now, as 2021 comes to an end, we can look back and assess what’s been accomplished and what’s ahead in 2022 “opportunity wise,” and the challenges they bring with them. Forward in Flight the only magazine dedicated exclusively to Wisconsin aviation history and today’s aviation events. Tom Eisele, editor W8863 U.S. Highway 12 Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-9762 513-484-0394 t.d.eisele@att.net The Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame is a non-profit membership organization with a mission to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, recognize those who made that history, inform others of it, and promote aviation education for future generations. Chris Campbell watching General Oelstrom’s video at 2021 WAHF Induction ceremony. Our Mission is to collect and preserve the history of aviation in Wisconsin, to recognize those who made that history, to inform others of it, and to promote aviation education for future generations. Your WAHF Board does that throughout the year and it all came together in the home of the Experimental Aircraft Association this fall in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Thank all of you who came to the EAA Museum in Oshkosh and participated in the Induction Ceremony in the Eagle Hangar on October 23, 2021! You are all now a part of the History of Aviation in Wisconsin! WAHF Addendum ~ We missed Board Member Jimmy Szajkovics at the ceremony, as he was hospitalized with followup back surgery because he had a “screw loose.” He’s recovering at home now and wanted to let you all know it actually was a back screw that was installed in the initial surgery, not a “screw loose” between his ears. And for many of you, your WAHF membership expires at the end of this year and this issue of FIF being your last issue as well. Please renew your membership, so that we can continue to bring great articles about aviation history in Wisconsin and about those who created it. On the cover: John Schwister, the first Wisconsinite to create and fly a homebuilt airplane (1911). Photo in the public domain

WEEDEN’S REVIEW “I Had No Idea!” Grand Opening at the Kelch Aviation Museum By Patrick Weeden I’ve been working away in isolation and cornfields in Wisconsin on a fool’s errand: A world class museum about something dusty and old, in a town of less than 3,000 people. Why? Because it needed to be done, and this was the place to do it. Brodhead’s mayor once asked me why I thought an aviation museum would succeed at Brodhead Airport; I replied that Brodhead Airport was the only place it could succeed. Alfred and Lois Kelch had been amassWelcome to the main museum hangar, “The Bill and Sue Knight ing a priceless collection of vintage aircraft and assoMemorial Vintage Aviation Hangar.” ciated artifacts since the late 1960s, and had left instructions and funding to create a museum after negatives, publications, and general records. In early 2020, the they died. While their home was Mequon, Wisconsin, Brodhead museum’s main hangar was completed and soon stored the muAirport had become the Kelch family flying base by the 1990s, seum’s own collection plus the WAHF archives. This year, so it seemed a natural place for the museum. After all, it was a however, we were excited to move both these extensive collecrenowned regional gathering place for like-minded collectors tions into the museum’s new climate-controlled archival space, and restorers of antique and vintage aircraft, and had hosted their forever home. several large fly-in events each year. Excited about moving a library? Yes, but more so, the new By 2012, a non-profit educational corporation was created, archive space is part of a spacious and much-anticipated Phase and in 2015, work began in earnest to fulfill Al and Lois’s II museum building, complete with event space, restrooms, and dream. By this time, the Kelch collection was scattered among all the accessible amenities required to open to the public. After multiple hangars and in varying stages of preservation. It was years of fundraising, planning, and hoping, in one rushed month time to bring it all together under one roof and make it accessithe Kelch Aviation Museum went from closed collection to pubble to the public. By 2019, sufficient funds were raised to break lic institution. On July 23rd, 2021 -- and you’d better believe ground on the first phase of construction, completed in February that no one on the museum team had slept since June -- a ribbon 2020. cutting ceremony was held in the blazing morning sunshine, and My charming workplace, the Kelch Aviation Museum, has suddenly we were a Museum with a capital M. housed Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame archives since 2020 If you attended this thrilling event of the century, you no a collection containing all manner of files, photographs and doubt were overwhelmed by the swooning crowds, gasped with excitement listening to an endless array of Important People, and sweat through your T-shirt waiting to get inside the new facilities (if only to try the free ice cream). If you weren’t there, you must have seen the world headlines and live national television coverage, or have otherwise been bombarded with advertising and social media posts of the event… Or not. But I’m here to tell you, the grand opening truly lived up to all the talk about “that new museum at Brodhead Airport.” On the morning of our very first day of public operation, my small staff and I gathered a few minutes before unlocking the doors. It was the first calm moment in several weeks, and suddenly reality hit. One of us (nobody remembers who) exclaimed, “Holy cow, we’re open to the public! What do we do now?!” Before that day, I often joked that we were only a museum because we said we were. We had all of the stuff, all the paperwork, all the ideas - but we didn’t have a MUSEUM, a building, Kelch Aviation Museum board President, Jeff Beyer, addresses a home. Here it was, the moment we’d been working towards the guests at the grand opening ceremony. for over six years: Raising $1.2 million, endless planning, 2 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame

WEEDEN’S REVIEW The staff working “on the floor” have become pretty skilled at learning as much from the visitors as they learn from us. How they found out about the museum, where they came from -- but more than that, we want to know what compelled them to explore our niche little world of antique aviation. We get all sorts of detailed responses. The aviation people had no idea such a rich collection of flyable vintage aircraft existed in Wisconsin. The families had no idea that vintage aviation preservation was even a thing. The kids didn’t know airplanes were this big or beautiful, or that you could build one in your garage. And the staff has started to say, “I had no idea… .” No idea that folks would care. No idea the people we would meet, the careers we would inspire, the Sandra Joranlien and family cut the ribbon at the grand opening of the “Kent Joranlien stories we would hear. No idea we could Memorial Fellowship Hall” at the Kelch Aviation Museum (Friday, July 23, 2021). really be a Museum, capital M. complicated construction, late nights and long days. I turned the Every day presents some unexpected new challenge, and key and swung the door open. Open, to share the joy of aviation lately I wonder if I’m a museum director at all, or if my job has with the public. morphed into some kind of babysitter-wedding-planner-tourAs the hangar doors went up, visitors saw two brand-new guide? But then some old pilot tells a first-solo story, or a kid steel hangars, over 16,000 sq.ft. of floor space, 20 vintage airasks a clever question, and there’s no denying that, gosh darn it, craft (most in flying condition), rare engines, a dozen interactive we’ve done it. The Kelch Aviation Museum is fulfilling its misdisplays, a kid’s area, and acres of signage that told the story sion: Sharing the thrill, the science, the inspiration of aviation’s behind each artifact. People from near and far stepped inside, history. eyes and mouths wide open as they took it all in. All day, all weekend, we heard one phrase over and over: Future displays will include Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame material as well as rotating exhibits featuring our aircraft and “Wow! I had no idea!” artifact collection. Workshops and events are open to the public, while the facilities can be rented for all manner of private Over our three-day grand opening weekend, the museum hosted events. For an especially in-depth and personalized experience, nearly 1,000 visitors from all corners of the country (and several take a tour with one of our staff - Kent has worked on every airother countries to boot). Dozens of people pulled me or my staff plane, Ami will charm your kids, Hannah knows Bernard Pietenaside to say, “I had no idea this was here. I had no idea this pol like family, and Joe will probably find someone you know in collection was so extensive! I had no idea Brodhead had a mucommon. seum! I had no idea.” In the months since that first weekend of excitement, a daily routine has developed during our open hours. Wednesday through Sunday, 10:00 a.m. to Another view of 4:00 p.m., our doors are open and we welcome all the inviting enkinds of visitors. Some have been following our trance to “The Bill progress for years; some heard about the place and Sue Knight Memorial Vintage from a friend or read about it in that morning’s Aviation Hangar” paper. Some live just down the road and some travel hours to get here. On good days there are a hundred visitors and on slower days just a handful. There are aviation nerds (like all of us) and there are families looking for something to do with the Patrick Weeden is the Executive Director of the Kelch Aviation kids. We see a lot of couples on day trips, retirees and veterans, Museum at Brodhead Airport (C37), a Board member of the and history buffs. Some know nothing about aviation, some are Brodhead Pietenpol Assn., and a Board member of WAHF. professional pilots... . But nearly every day, without exception, He is a private pilot and has been involved with vintage aircraft someone walks in, stops, stares, and says breathlessly, “Wow! I operation and restoration since childhood. had no idea.” All photos courtesy of Patrick Weeden 3 Forward in Flight – Winter 2021-2022

MEDICAL MATTERS Prevention, CT Scans, and Early Detection of Lung Cancer “Smoke ‘em if you got ‘em?” No, Not Anymore By Dr. Reid Sousek, Senior AME While my recent articles have mostly been about the medical application, exam, or disease-related certification, this time we will circle back and get in front of a disease. Let’s discuss prevention or early detection. I believe that our approach to medicine in the United States is often upside down. We spend an immense amount of money on end-stage conditions (in the form of medications and treatments once a disease has been diagnosed), rather than spending a little bit of money earlier on prevention or detection. In the individual patient, it is often hard to prove that some disease did not happen specifically because of a preventive intervention. Still, the benefits of early detection may be clearly seen in a comparison of large groups of patients. But, doubleblinded studies with large groups of patients require large amounts of funding, and so they are rare. Unfortunately, the amount of money floating around for preventive studies pales in comparison to what is spent by drug companies on development of new drugs. A quick internet search shows that in 2019 $9.5 billion dollars were spent by the NIH on prevention (https:// report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/). In 2013, that investment was as low as $6.7 billion dollars. Considering the limited funding of research, and the challenge of developing these studies in the field of prevention, it is remarkable that the USPSTF can make evidence-based recommendations. But, they do! Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry spent $83 billion dollars on research and development in 2019 (https:// www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-04/57025-Rx-RnD.pdf). This number has skyrocketed over the years, and is 10 times the amount that was spent in 1980. Clearly, there’s money to be made in pharmaceuticals. About 10 years ago, when I dabbled in some administrative roles in clinic leadership, I was sitting in a meeting with medical group leaders, health insurance plan leaders, and a physician consultant (more of a salesman than a true clinician). The salesman physician was rambling on about some service they could sell us that would provide close monitoring of our most poorly controlled diabetics. This type of monitoring had already been promised as an upcoming feature of the Electronic Medical Record --but it never actually worked. It is not realistic for a physician responsible for a patient panel of 3000 to 4000 individuals to be able to stay on top of this condition without effective tools. So, we had to look towards another program (frankly, the most reliable feature 4 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame of any Electronic Medical Record is turning the clinicians’ attention towards treating the computer rather than the patient). I could tell that one of the other physicians at the meeting was getting more and more exasperated at the over-selling. Finally, he said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. If a bunch of horses are running off a cliff, do we go to the bottom of the cliff and work on the injured horses; or do we go to the top of the cliff and stop the other horses?” The room fell quiet. That comment drilled down to the essence of preventive medicine. By spending a little bit of money now, we hopefully can save a lot later. But, more importantly, we might be able to save people a lot of pain, stress, and suffering. I assume most of us do the recommended pre-flight and routine maintenance on our airplanes, so, why wouldn’t we do the same for our bodies? Better to detect a malignant growth now, than when it has already spread to the lymph nodes. Application in Aviation How would screening and early detection help aviators? Though entire books and journals are dedicated to screening recommendations, here we will focus on one recently updated United States Preventive Screening Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation. The USPSTF is a group of 16 volunteer members with expertise in prevention, evidence-based medicine, and primary care. There are members with backgrounds in Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Obstetrics/Gynecology, and Nursing. After reviewing available evidence, the group makes a recommendation. These recommendations are graded A, B, C, D, or I. An “A” recommendation means this service or intervention should be performed, and there is high certainty that its net benefit is substantial. As the letters progress, the benefit becomes less clear or obvious; and a “D” recommendation means there is no net benefit, or the harms outweigh the benefits. An “I” recommendation means there is insufficient data or conflicting data. One of the recently updated recommendations was released in March when the USPSTF provided updated guidance on lung cancer screening. Yes, the most logical preventive measure here is tobacco avoidance and cessation, and counseling adults on tobacco

MEDICAL MATTERS smoking cessation has an “A” rating. An estimated 90% of lung cancer cases are related to smoking. Smokers have a 20 times higher relative risk of lung cancer than non-smokers. With current screening (or lack thereof), the median age to diagnose lung cancer is 70 years, with a five year survival rate around 20%. As expected, early-stage lung cancer carries a better prognosis and is more likely to respond to treatment. In terms of the scope of the problem, lung cancer is reported to be the 2nd most common cancer in both men and women. According to the American Cancer Society (www.cancer.org/ cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html), over 130,000 people will die from lung cancer, and 235,000 will be diagnosed with lung cancer, in 2021. Another way to see the scope of this disease is to consider that more people will die of lung cancer than colon cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer combined. Fortunately, as rates of smoking decrease (through adoption of the avoidance and cessation measures mentioned above), the rates of lung cancer are also decreasing. The problem is that it’s difficult to get people to believe how important prevention and early detection are, since it takes years to see the fruits of those efforts. Our society, however, wants to see results now. If understanding why prevention and early detection are very good practices, what is the recent recommendation? The USPSTF recommends yearly low dose computed tomography (low dose CT) for adults 50 to 80 years old who have at least a 20-pack-year smoking history and who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. A pack-year is generally defined as 1 pack of cigarettes per day for one year. Similarly, smoking a half-pack of cigarettes per day for 40 years would equate to 20 pack-years. The above recommendation also states that this screening should be stopped once an individual has not smoked for 15 years, or has a condition that would significantly limit life expectancy or ability to tolerate curative therapy. This recommendation is considered “B,” meaning that there is moderate certainty of benefit. It does, however, admit that there may be some potential harms, such as false-positives, that may result in unnecessary invasive testing or anxiety. Low dose CT scans have become a reality. Newer scanners can produce high-resolution images with a significantly lower radiation dose than previous generations of scanners. This scan is performed without contrast and can be performed in a single 25 second scan. The images may produce resolution down to 1 mm. Many may ask, “Why not just start with a chest x-ray?” Research studies as far back as the 1960’s have not shown any mortality benefit with the use of screening chest x-rays alone. However, if a chest x-ray is performed for another reason (such as evaluating pneumonia), then any identified nodules will be worked up further. If a concerning area is identified, the next step of evaluation is aimed at getting enough information to guide diagnostic biopsy, staging, and treatment options. In many cases, a CT scan with intravenous contrast is performed, as this helps more easily to view the mediastinum and also to identify vascular structures. Imaging of the adrenal glands and liver are also occasionally performed. If a lesion is discovered, then depending upon the location, a lesion may be biopsied using bronchoscopy. Or, in other cases, an open surgical procedure or video-assisted thoracic surgery may be performed. During this evaluation and active treatment phase, the pilot being treated would likely be grounded. CFR Part 61.53 states that a medical certificate holder shall not act as pilot in command, or in any other capacity as a required pilot flight crewmember, while that person: 1 - Knows or has reason to know of any medical condition that would make the person unable to meet the requirements for the medical certificate necessary for the pilot operation 2 - Is taking medication or receiving other treatment for a medical condition that results in the person being unable to meet the requirements for the medical certificate necessary for pilot operation. If a pilot has a favorable outcome, with complete resection of a lesion without recurrence (or metastasis), certification may be possible. As usual, the FAA will want to review surgical, oncology, imaging reports and also a current status report from the treating provider. My “family medicine” background may shine through in my strong faith in preventive measures. While discovering lung cancer at any age is scary, knowing about it as early as possible will improve the chances for a cure. And, if a lung cancer is detected, early detection may allow for less aggressive treatments and associated side effects. I hope that in 5 or 10 years, writing an article on smoking and lung cancer would only apply to a tiny subset of people, and not to 41 million American adults (16%) who are smokers in 2021. Counseling and lung cancer detection are just one preventive measure that may limit pain, suffering, and death. Be on the lookout for others. [Dr. Reid Sousek is an FAA-designated Senior Aviation Medical Examiner, who offers Class 1, Class 2, and Class 3 Pilot Medical Exams; and an HIMS AME, for drug/alcohol exams. Dr. Sousek has offices near Oshkosh and Menasha.] 5 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2021-2022

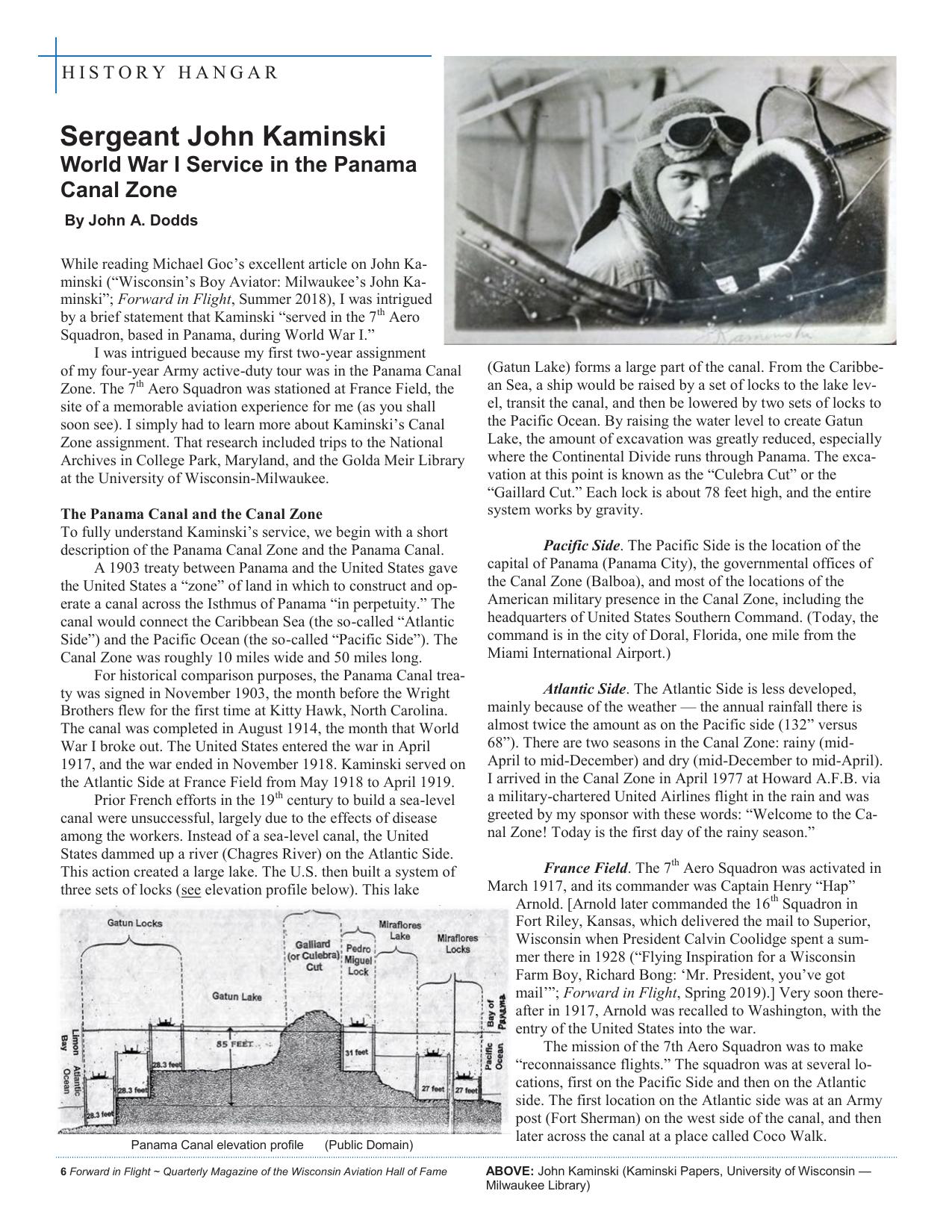

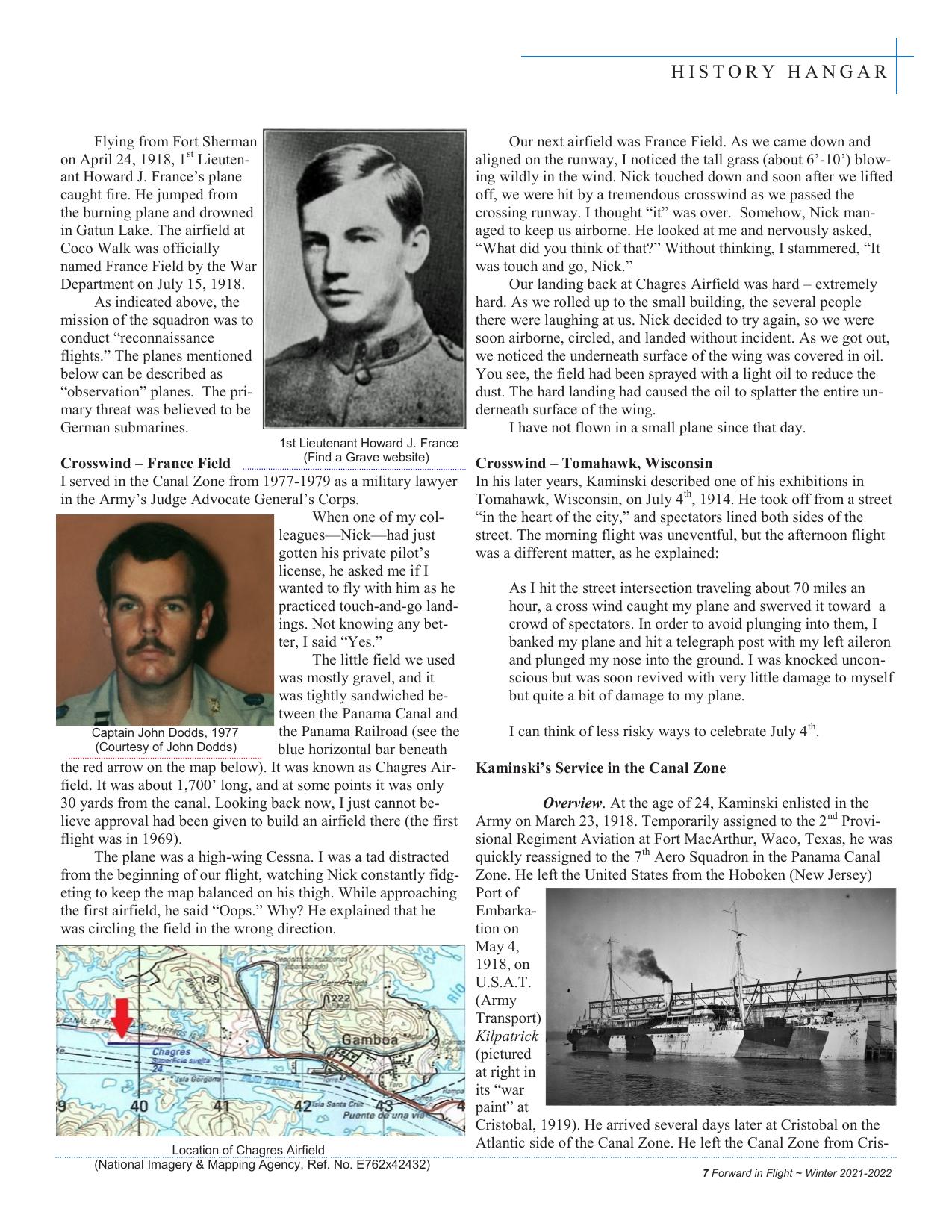

HISTORY HANGAR Sergeant John Kaminski World War I Service in the Panama Canal Zone By John A. Dodds While reading Michael Goc’s excellent article on John Kaminski (“Wisconsin’s Boy Aviator: Milwaukee’s John Kaminski”; Forward in Flight, Summer 2018), I was intrigued by a brief statement that Kaminski “served in the 7th Aero Squadron, based in Panama, during World War I.” I was intrigued because my first two-year assignment of my four-year Army active-duty tour was in the Panama Canal Zone. The 7th Aero Squadron was stationed at France Field, the site of a memorable aviation experience for me (as you shall soon see). I simply had to learn more about Kaminski’s Canal Zone assignment. That research included trips to the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and the Golda Meir Library at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The Panama Canal and the Canal Zone To fully understand Kaminski’s service, we begin with a short description of the Panama Canal Zone and the Panama Canal. A 1903 treaty between Panama and the United States gave the United States a “zone” of land in which to construct and operate a canal across the Isthmus of Panama “in perpetuity.” The canal would connect the Caribbean Sea (the so-called “Atlantic Side”) and the Pacific Ocean (the so-called “Pacific Side”). The Canal Zone was roughly 10 miles wide and 50 miles long. For historical comparison purposes, the Panama Canal treaty was signed in November 1903, the month before the Wright Brothers flew for the first time at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The canal was completed in August 1914, the month that World War I broke out. The United States entered the war in April 1917, and the war ended in November 1918. Kaminski served on the Atlantic Side at France Field from May 1918 to April 1919. Prior French efforts in the 19th century to build a sea-level canal were unsuccessful, largely due to the effects of disease among the workers. Instead of a sea-level canal, the United States dammed up a river (Chagres River) on the Atlantic Side. This action created a large lake. The U.S. then built a system of three sets of locks (see elevation profile below). This lake Panama Canal elevation profile (Public Domain) 6 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame (Gatun Lake) forms a large part of the canal. From the Caribbean Sea, a ship would be raised by a set of locks to the lake level, transit the canal, and then be lowered by two sets of locks to the Pacific Ocean. By raising the water level to create Gatun Lake, the amount of excavation was greatly reduced, especially where the Continental Divide runs through Panama. The excavation at this point is known as the “Culebra Cut” or the “Gaillard Cut.” Each lock is about 78 feet high, and the entire system works by gravity. Pacific Side. The Pacific Side is the location of the capital of Panama (Panama City), the governmental offices of the Canal Zone (Balboa), and most of the locations of the American military presence in the Canal Zone, including the headquarters of United States Southern Command. (Today, the command is in the city of Doral, Florida, one mile from the Miami International Airport.) Atlantic Side. The Atlantic Side is less developed, mainly because of the weather — the annual rainfall there is almost twice the amount as on the Pacific side (132” versus 68”). There are two seasons in the Canal Zone: rainy (midApril to mid-December) and dry (mid-December to mid-April). I arrived in the Canal Zone in April 1977 at Howard A.F.B. via a military-chartered United Airlines flight in the rain and was greeted by my sponsor with these words: “Welcome to the Canal Zone! Today is the first day of the rainy season.” France Field. The 7th Aero Squadron was activated in March 1917, and its commander was Captain Henry “Hap” Arnold. [Arnold later commanded the 16 th Squadron in Fort Riley, Kansas, which delivered the mail to Superior, Wisconsin when President Calvin Coolidge spent a summer there in 1928 (“Flying Inspiration for a Wisconsin Farm Boy, Richard Bong: ‘Mr. President, you’ve got mail’”; Forward in Flight, Spring 2019).] Very soon thereafter in 1917, Arnold was recalled to Washington, with the entry of the United States into the war. The mission of the 7th Aero Squadron was to make “reconnaissance flights.” The squadron was at several locations, first on the Pacific Side and then on the Atlantic side. The first location on the Atlantic side was at an Army post (Fort Sherman) on the west side of the canal, and then later across the canal at a place called Coco Walk. ABOVE: John Kaminski (Kaminski Papers, University of Wisconsin — Milwaukee Library)

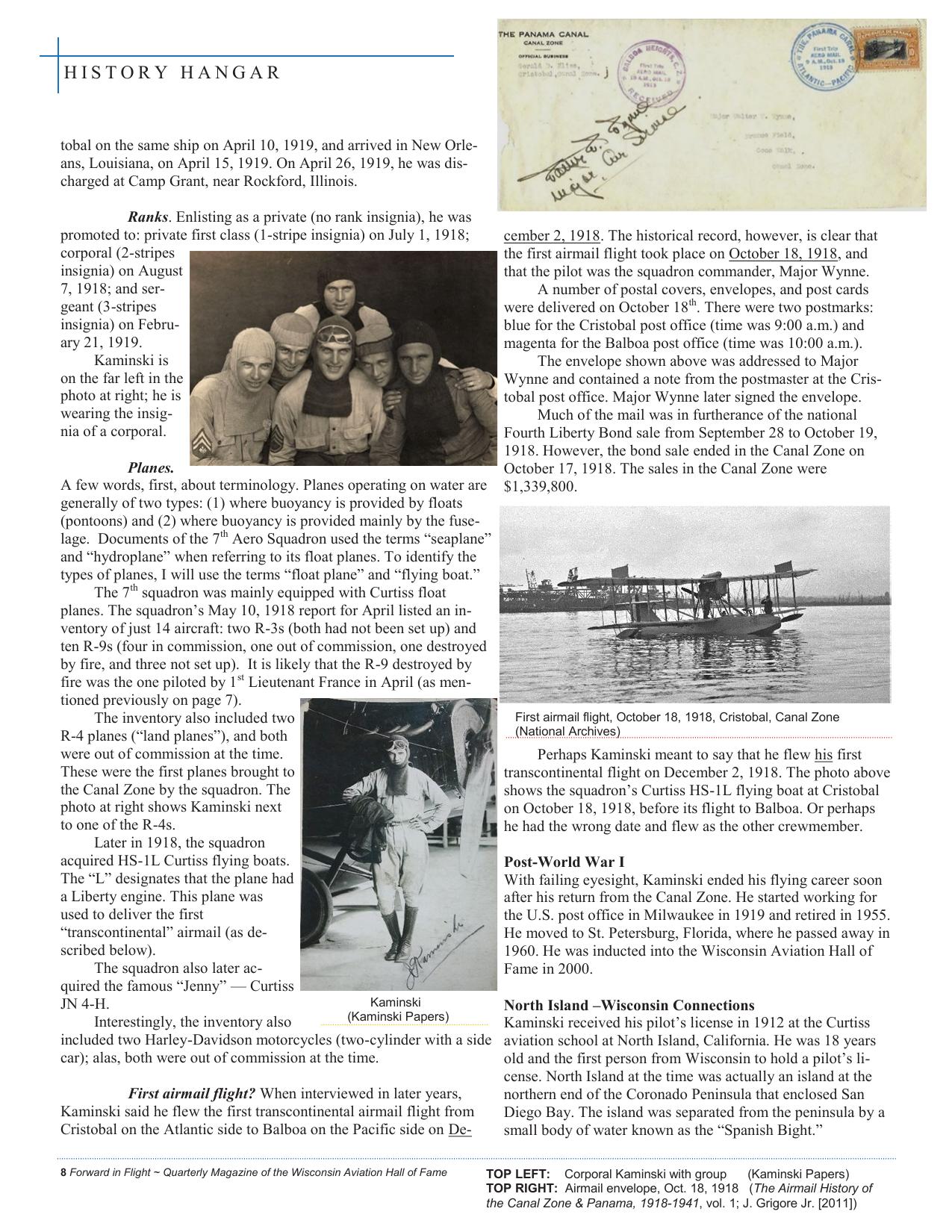

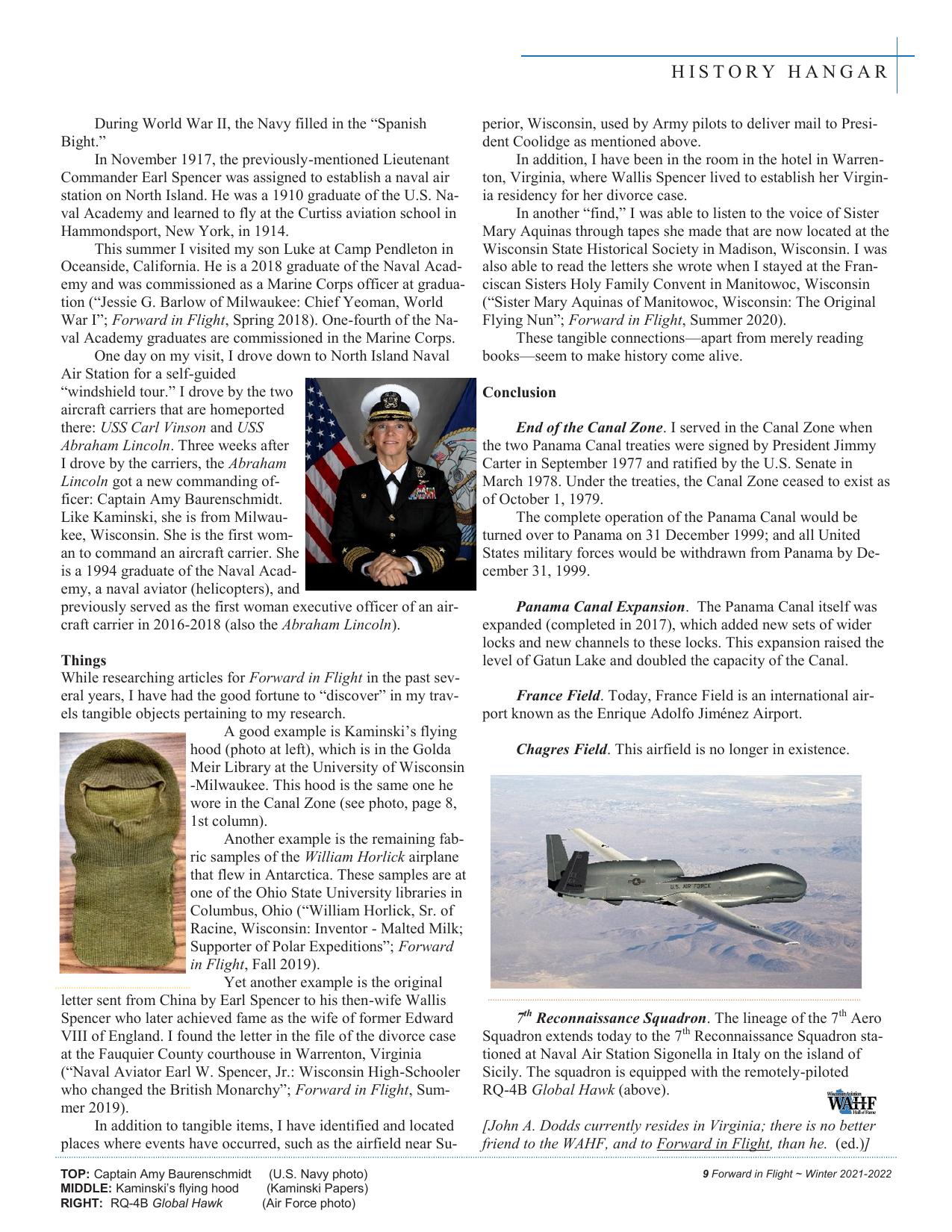

HISTORY HANGAR Flying from Fort Sherman on April 24, 1918, 1st Lieutenant Howard J. France’s plane caught fire. He jumped from the burning plane and drowned in Gatun Lake. The airfield at Coco Walk was officially named France Field by the War Department on July 15, 1918. As indicated above, the mission of the squadron was to conduct “reconnaissance flights.” The planes mentioned below can be described as “observation” planes. The primary threat was believed to be German submarines. Our next airfield was France Field. As we came down and aligned on the runway, I noticed the tall grass (about 6’-10’) blowing wildly in the wind. Nick touched down and soon after we lifted off, we were hit by a tremendous crosswind as we passed the crossing runway. I thought “it” was over. Somehow, Nick managed to keep us airborne. He looked at me and nervously asked, “What did you think of that?” Without thinking, I stammered, “It was touch and go, Nick.” Our landing back at Chagres Airfield was hard – extremely hard. As we rolled up to the small building, the several people there were laughing at us. Nick decided to try again, so we were soon airborne, circled, and landed without incident. As we got out, we noticed the underneath surface of the wing was covered in oil. You see, the field had been sprayed with a light oil to reduce the dust. The hard landing had caused the oil to splatter the entire underneath surface of the wing. I have not flown in a small plane since that day. 1st Lieutenant Howard J. France (Find a Grave website) Crosswind – France Field I served in the Canal Zone from 1977-1979 as a military lawyer in the Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps. When one of my colleagues—Nick—had just gotten his private pilot’s license, he asked me if I wanted to fly with him as he practiced touch-and-go landings. Not knowing any better, I said “Yes.” The little field we used was mostly gravel, and it was tightly sandwiched between the Panama Canal and the Panama Railroad (see the Captain John Dodds, 1977 (Courtesy of John Dodds) blue horizontal bar beneath the red arrow on the map below). It was known as Chagres Airfield. It was about 1,700’ long, and at some points it was only 30 yards from the canal. Looking back now, I just cannot believe approval had been given to build an airfield there (the first flight was in 1969). The plane was a high-wing Cessna. I was a tad distracted from the beginning of our flight, watching Nick constantly fidgeting to keep the map balanced on his thigh. While approaching the first airfield, he said “Oops.” Why? He explained that he was circling the field in the wrong direction. Location of Chagres Airfield (National Imagery & Mapping Agency, Ref. No. E762x42432) Crosswind – Tomahawk, Wisconsin In his later years, Kaminski described one of his exhibitions in Tomahawk, Wisconsin, on July 4th, 1914. He took off from a street “in the heart of the city,” and spectators lined both sides of the street. The morning flight was uneventful, but the afternoon flight was a different matter, as he explained: As I hit the street intersection traveling about 70 miles an hour, a cross wind caught my plane and swerved it toward a crowd of spectators. In order to avoid plunging into them, I banked my plane and hit a telegraph post with my left aileron and plunged my nose into the ground. I was knocked unconscious but was soon revived with very little damage to myself but quite a bit of damage to my plane. I can think of less risky ways to celebrate July 4 th. Kaminski’s Service in the Canal Zone Overview. At the age of 24, Kaminski enlisted in the Army on March 23, 1918. Temporarily assigned to the 2 nd Provisional Regiment Aviation at Fort MacArthur, Waco, Texas, he was quickly reassigned to the 7th Aero Squadron in the Panama Canal Zone. He left the United States from the Hoboken (New Jersey) Port of Embarkation on May 4, 1918, on U.S.A.T. (Army Transport) Kilpatrick (pictured at right in its “war paint” at Cristobal, 1919). He arrived several days later at Cristobal on the Atlantic side of the Canal Zone. He left the Canal Zone from Cris7 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2021-2022

HISTORY HANGAR tobal on the same ship on April 10, 1919, and arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana, on April 15, 1919. On April 26, 1919, he was discharged at Camp Grant, near Rockford, Illinois. Ranks. Enlisting as a private (no rank insignia), he was promoted to: private first class (1-stripe insignia) on July 1, 1918; corporal (2-stripes insignia) on August 7, 1918; and sergeant (3-stripes insignia) on February 21, 1919. Kaminski is on the far left in the photo at right; he is wearing the insignia of a corporal. Planes. A few words, first, about terminology. Planes operating on water are generally of two types: (1) where buoyancy is provided by floats (pontoons) and (2) where buoyancy is provided mainly by the fuselage. Documents of the 7th Aero Squadron used the terms “seaplane” and “hydroplane” when referring to its float planes. To identify the types of planes, I will use the terms “float plane” and “flying boat.” The 7th squadron was mainly equipped with Curtiss float planes. The squadron’s May 10, 1918 report for April listed an inventory of just 14 aircraft: two R-3s (both had not been set up) and ten R-9s (four in commission, one out of commission, one destroyed by fire, and three not set up). It is likely that the R-9 destroyed by fire was the one piloted by 1st Lieutenant France in April (as mentioned previously on page 7). The inventory also included two R-4 planes (“land planes”), and both were out of commission at the time. These were the first planes brought to the Canal Zone by the squadron. The photo at right shows Kaminski next to one of the R-4s. Later in 1918, the squadron acquired HS-1L Curtiss flying boats. The “L” designates that the plane had a Liberty engine. This plane was used to deliver the first “transcontinental” airmail (as described below). The squadron also later acquired the famous “Jenny” — Curtiss Kaminski JN 4-H. (Kaminski Papers) Interestingly, the inventory also included two Harley-Davidson motorcycles (two-cylinder with a side car); alas, both were out of commission at the time. First airmail flight? When interviewed in later years, Kaminski said he flew the first transcontinental airmail flight from Cristobal on the Atlantic side to Balboa on the Pacific side on De8 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame cember 2, 1918. The historical record, however, is clear that the first airmail flight took place on October 18, 1918, and that the pilot was the squadron commander, Major Wynne. A number of postal covers, envelopes, and post cards were delivered on October 18th. There were two postmarks: blue for the Cristobal post office (time was 9:00 a.m.) and magenta for the Balboa post office (time was 10:00 a.m.). The envelope shown above was addressed to Major Wynne and contained a note from the postmaster at the Cristobal post office. Major Wynne later signed the envelope. Much of the mail was in furtherance of the national Fourth Liberty Bond sale from September 28 to October 19, 1918. However, the bond sale ended in the Canal Zone on October 17, 1918. The sales in the Canal Zone were $1,339,800. First airmail flight, October 18, 1918, Cristobal, Canal Zone (National Archives) Perhaps Kaminski meant to say that he flew his first transcontinental flight on December 2, 1918. The photo above shows the squadron’s Curtiss HS-1L flying boat at Cristobal on October 18, 1918, before its flight to Balboa. Or perhaps he had the wrong date and flew as the other crewmember. Post-World War I With failing eyesight, Kaminski ended his flying career soon after his return from the Canal Zone. He started working for the U.S. post office in Milwaukee in 1919 and retired in 1955. He moved to St. Petersburg, Florida, where he passed away in 1960. He was inducted into the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame in 2000. North Island –Wisconsin Connections Kaminski received his pilot’s license in 1912 at the Curtiss aviation school at North Island, California. He was 18 years old and the first person from Wisconsin to hold a pilot’s license. North Island at the time was actually an island at the northern end of the Coronado Peninsula that enclosed San Diego Bay. The island was separated from the peninsula by a small body of water known as the “Spanish Bight.” TOP LEFT: Corporal Kaminski with group (Kaminski Papers) TOP RIGHT: Airmail envelope, Oct. 18, 1918 (The Airmail History of the Canal Zone & Panama, 1918-1941, vol. 1; J. Grigore Jr. [2011])

HISTORY HANGAR During World War II, the Navy filled in the “Spanish Bight.” In November 1917, the previously-mentioned Lieutenant Commander Earl Spencer was assigned to establish a naval air station on North Island. He was a 1910 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and learned to fly at the Curtiss aviation school in Hammondsport, New York, in 1914. This summer I visited my son Luke at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California. He is a 2018 graduate of the Naval Academy and was commissioned as a Marine Corps officer at graduation (“Jessie G. Barlow of Milwaukee: Chief Yeoman, World War I”; Forward in Flight, Spring 2018). One-fourth of the Naval Academy graduates are commissioned in the Marine Corps. One day on my visit, I drove down to North Island Naval Air Station for a self-guided “windshield tour.” I drove by the two aircraft carriers that are homeported there: USS Carl Vinson and USS Abraham Lincoln. Three weeks after I drove by the carriers, the Abraham Lincoln got a new commanding officer: Captain Amy Baurenschmidt. Like Kaminski, she is from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. She is the first woman to command an aircraft carrier. She is a 1994 graduate of the Naval Academy, a naval aviator (helicopters), and previously served as the first woman executive officer of an aircraft carrier in 2016-2018 (also the Abraham Lincoln). Things While researching articles for Forward in Flight in the past several years, I have had the good fortune to “discover” in my travels tangible objects pertaining to my research. A good example is Kaminski’s flying hood (photo at left), which is in the Golda Meir Library at the University of Wisconsin -Milwaukee. This hood is the same one he wore in the Canal Zone (see photo, page 8, 1st column). Another example is the remaining fabric samples of the William Horlick airplane that flew in Antarctica. These samples are at one of the Ohio State University libraries in Columbus, Ohio (“William Horlick, Sr. of Racine, Wisconsin: Inventor - Malted Milk; Supporter of Polar Expeditions”; Forward in Flight, Fall 2019). Yet another example is the original letter sent from China by Earl Spencer to his then-wife Wallis Spencer who later achieved fame as the wife of former Edward VIII of England. I found the letter in the file of the divorce case at the Fauquier County courthouse in Warrenton, Virginia (“Naval Aviator Earl W. Spencer, Jr.: Wisconsin High-Schooler who changed the British Monarchy”; Forward in Flight, Summer 2019). In addition to tangible items, I have identified and located places where events have occurred, such as the airfield near SuTOP: Captain Amy Baurenschmidt (U.S. Navy photo) MIDDLE: Kaminski’s flying hood (Kaminski Papers) RIGHT: RQ-4B Global Hawk (Air Force photo) perior, Wisconsin, used by Army pilots to deliver mail to President Coolidge as mentioned above. In addition, I have been in the room in the hotel in Warrenton, Virginia, where Wallis Spencer lived to establish her Virginia residency for her divorce case. In another “find,” I was able to listen to the voice of Sister Mary Aquinas through tapes she made that are now located at the Wisconsin State Historical Society in Madison, Wisconsin. I was also able to read the letters she wrote when I stayed at the Franciscan Sisters Holy Family Convent in Manitowoc, Wisconsin (“Sister Mary Aquinas of Manitowoc, Wisconsin: The Original Flying Nun”; Forward in Flight, Summer 2020). These tangible connections—apart from merely reading books—seem to make history come alive. Conclusion End of the Canal Zone. I served in the Canal Zone when the two Panama Canal treaties were signed by President Jimmy Carter in September 1977 and ratified by the U.S. Senate in March 1978. Under the treaties, the Canal Zone ceased to exist as of October 1, 1979. The complete operation of the Panama Canal would be turned over to Panama on 31 December 1999; and all United States military forces would be withdrawn from Panama by December 31, 1999. Panama Canal Expansion. The Panama Canal itself was expanded (completed in 2017), which added new sets of wider locks and new channels to these locks. This expansion raised the level of Gatun Lake and doubled the capacity of the Canal. France Field. Today, France Field is an international airport known as the Enrique Adolfo Jiménez Airport. Chagres Field. This airfield is no longer in existence. 7th Reconnaissance Squadron. The lineage of the 7th Aero Squadron extends today to the 7th Reconnaissance Squadron stationed at Naval Air Station Sigonella in Italy on the island of Sicily. The squadron is equipped with the remotely-piloted RQ-4B Global Hawk (above). [John A. Dodds currently resides in Virginia; there is no better friend to the WAHF, and to Forward in Flight, than he. (ed.)] 9 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2021-2022

SHORT STORY Demon Ice For Stephen, who loves to fly By Dean Zakos I always wanted to fly. I liked the satisfaction of rising up and meeting challenges. I thrived on being presented with, or happily sought out, opportunities to test myself. I wanted to see how I performed – in school, in sports, or against other men in airplanes or helicopters. Did I measure up? I usually satisfied myself that I did. Well, I am being challenged tonight. I am flying alone in a Beechcraft B80 Queen Air. The airplane, a twin-engine corporate and light transport aircraft, is owned by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, my employer. It requires only a single pilot and can be configured for carrying up to eleven passengers or cargo. Max speed is 208 kts and normal cruise is about 180 - 190 kts. Max payload is 3,000 lbs. and GTOW is a little over 8,000 lbs. The B80 is powered by two Lycoming IGSO-540-A1D piston engines rated at 380 hp each. The wingspan is fifty feet, three inches and its length is thirty-five feet, six inches. I found it to have good flight characteristics and a pleasure to fly. In 1972, Lockheed was bidding on the US Army’s Cobra helicopter follow-on program with the AH-56A Cheyenne Advanced Attack compound helicopter. The Cheyenne had a fourblade main rotor, a four-blade tail rotor, an aft mounted threeblade pusher propeller, and low mounted aerodynamic wings, with hard points for launching anti-tank missiles and rockets. Powered by a single 4,275 shp GE-T64-716 turbo shaft engine, it flew at over 200 knots in some operational tests. Designed with a two-seat tandem cockpit, a gunner sat in the forward seat, which rotated 100 degrees to either side of centerline. This flexibility enabled the gunner to locate a target and remain lockedon to it regardless of the pilot’s flight maneuvers. The pilot occupied an elevated rear seat that offered excellent visibility to the front and sides. The prototype helicopter handled well and was fun to fly. Lockheed’s program was operating from a test area called the Castle Dome Development site at the Army’s huge Yuma Proving Grounds in Arizona. We had a good facility about 40 miles west of Yuma, with a single, non-lighted runway. A number of Lockheed employees decided to move temporarily to Yuma for the duration of the program. Others stayed in motels in Yuma during the week, opting to be shuttled from Burbank on Monday mornings and back to Burbank on Friday afternoons. These charter flights operated out of Laguna Army Airfield (KLGF), not far from Castle Dome. My wife and I decided to keep our family in the Los Angeles area, and so I became one of the weekly commuters. 10 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Because of my status as a test pilot on the project, I was offered an occasional respite from being a passenger on the weekly commuter flights. Lockheed had its own “personal transport” available for the project, the Beechcraft I am flying. Often, to maintain schedules, ferry personnel, or quickly confirm test results, I was asked, as needed, to fly parts, passengers, or test data to and from Yuma. I would usually depart Laguna on short notice and fly direct to Van Nuys (KVNY), which was located close to Lockheed’s facility. Earlier today, I was asked to make a “data run,” transporting test data containing many lines of specialized code. A Lockheed tech employee would meet me at the Van Nuys airport and then drive the data to Lockheed’s offices where people and computers “crunched the numbers” and interpreted the raw data. Reports generated from the data would then be loaded back on the Queen Air for the return flight to Yuma at the end of the same day and be available for review the next morning when the morning crew in Yuma came in for work. As I rotated the Queen Air and started my climb out of Yuma this morning, I took a moment to admire the painted colors of the desert slipping by below me. The vast ranges of sand and sagebrush, with layered purple mesas rising in the distance were stark, but beautiful. The Queen Air entered the overcast at just about 1,000 feet above the ground. The balance of the trip from Yuma to Van Nuys was solid IFR, with no precipitation, but with some snow showers possible in later forecasts for the return flight. Upon landing in Van Nuys, I was informed the data would take several hours longer than the normal three hour turnaround time to process, so the results would not be available for me to © Dean Zakos 2021. All rights reserved

SHORT STORY transport back to Yuma until that evening. I was actually pleased with the news, and I quickly grabbed a company car and headed home to spend a little time with my wife and three girls. After dinner that night, with goodnight hugs and kisses all around, I headed back to the airport, as I was advised the data had been processed and the stacks of completed reports were being loaded onto the plane. That scenario was pretty much how most data runs went. The return flight to Yuma ordinarily averaged about an hour and a half. This night, in early December 1972, was going to prove to be different. Winter weather conditions were moving into the area along my planned route. Snow was no longer forecast for my return to Yuma, but lower freezing levels and turbulence were. The Queen Air was equipped for winter operations, with wing de-icing boots, fuselage-mounted lights to confirm wing ice status, heated windshield de-ice, and prop de-ice. My IFR flight plan, with a 2100 (local) departure, was to climb to and maintain 6,000, Van Nuys direct Ontario. Then, direct Julian, direct Coyote Wells, Victor 137 to El Centro, then direct Yuma/Laguna. Flying the leg to Ontario, I encountered no significant weather, but there was some occasional moderate turbulence. I turned all de-ice equipment and pitot heat on as soon as I was in the clouds, except prop de-ice. On the leg to Julian, I experienced more turbulence and windshield ice was starting to form in corners and on protruding surfaces. I called LA Center and reported the ice, requesting another route. Center suggested a turn to 325 degrees, back toward Ontario, adding that two airliners had just departed Ontario and were not picking up ice. I made the turn and remained at 6,000 feet. I was not concerned – yet. My thoughts momentarily traveled back to earlier days and how I found myself sitting in the left seat of the Queen Air. Knowing of my interest in aviation as a boy, my father arranged for my first airplane ride. He had a friend who was the Chief Pilot for a large manufacturing company. The company owned a de Havilland DH.104 Dove, a twinengine, polished aluminum beauty, which was used to transport businessmen and customers. From that flight, I knew I wanted a career in aviation. I attended the University of Wisconsin and graduated in 1956. I met my wife there. While in the business school, I was also in an ROTC program. Upon graduation, I joined the Navy (a childhood dream of mine). At All images courtesy of Dean Zakos Pensacola, I was introduced to military flying, first in a Beech T-34 Mentor, then a North American T-28C Trojan. After winning my gold wings, I was assigned to a squadron flying Douglas A-4 Skyhawk attack jets. I flew two tours in Skyhawks from carrier decks (the USS Ranger CVA-61 and the USS Enterprise CVA-65) off the coast of North Vietnam until, on one mission, in a rapid descent while suffering with a head cold, one of my eardrums burst. I could no longer fly jets, so I asked for helicopters. I piloted a Sikorsky SH3A/D Sea King on an additional deployment in Vietnam. After my active duty service, I applied to the airlines and to some defense contractors. United Airlines and Lockheed offered me jobs. Both letters arrived in my mailbox the same day. My background was more a natural fit with Lockheed, as I was a “rotor head,” had acquired experience in the Navy as a “systems guy,” and had earned an MBA degree during one of my rotations to shore duty. I did encounter some ice in jets in the Navy, but we often flew so high and fast that ice was never really an issue. At 6,000 feet in the Queen Air, doing about 180 knots, picking up ice was a very real possibility. Ice continued to accrete on 11 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2021-2022

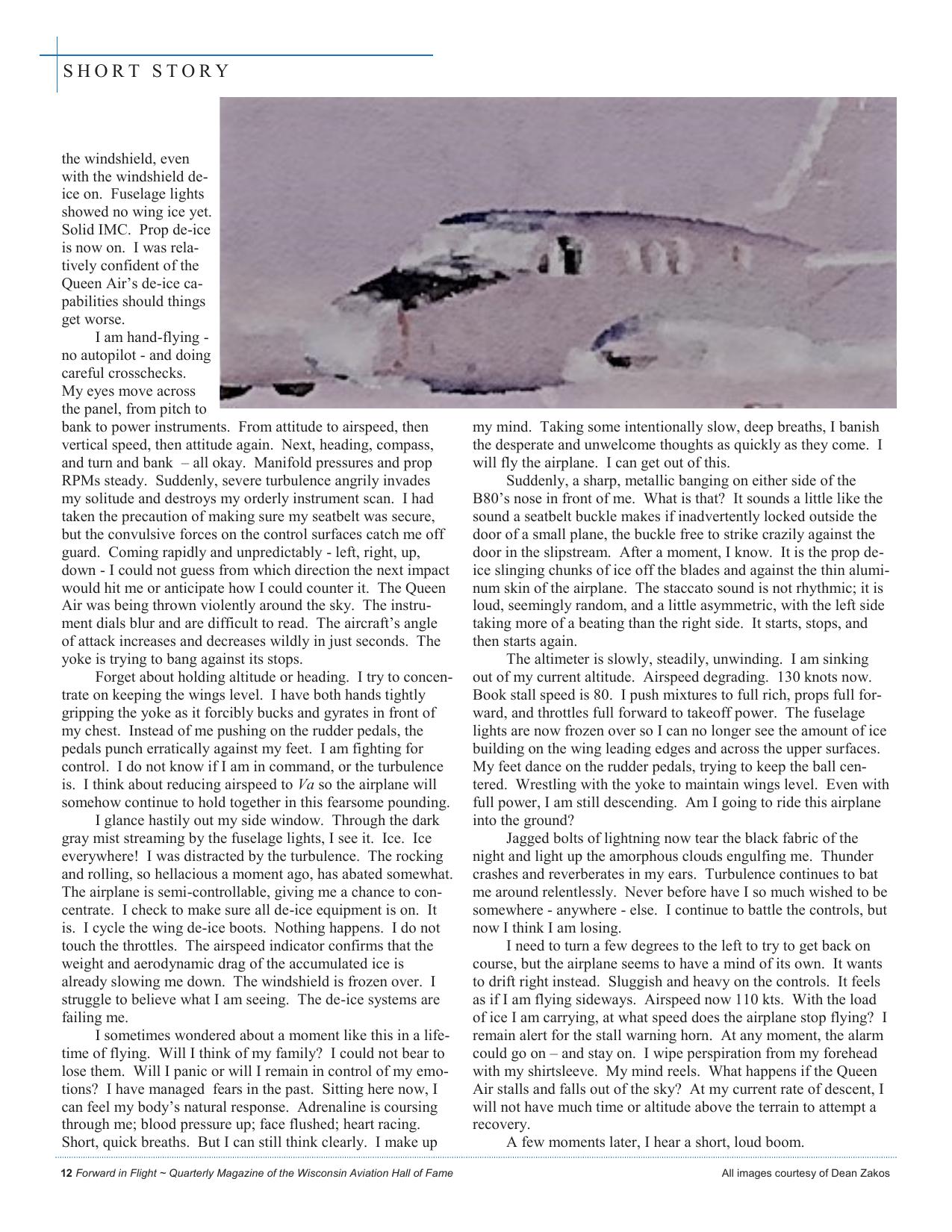

SHORT STORY the windshield, even with the windshield deice on. Fuselage lights showed no wing ice yet. Solid IMC. Prop de-ice is now on. I was relatively confident of the Queen Air’s de-ice capabilities should things get worse. I am hand-flying no autopilot - and doing careful crosschecks. My eyes move across the panel, from pitch to bank to power instruments. From attitude to airspeed, then vertical speed, then attitude again. Next, heading, compass, and turn and bank – all okay. Manifold pressures and prop RPMs steady. Suddenly, severe turbulence angrily invades my solitude and destroys my orderly instrument scan. I had taken the precaution of making sure my seatbelt was secure, but the convulsive forces on the control surfaces catch me off guard. Coming rapidly and unpredictably - left, right, up, down - I could not guess from which direction the next impact would hit me or anticipate how I could counter it. The Queen Air was being thrown violently around the sky. The instrument dials blur and are difficult to read. The aircraft’s angle of attack increases and decreases wildly in just seconds. The yoke is trying to bang against its stops. Forget about holding altitude or heading. I try to concentrate on keeping the wings level. I have both hands tightly gripping the yoke as it forcibly bucks and gyrates in front of my chest. Instead of me pushing on the rudder pedals, the pedals punch erratically against my feet. I am fighting for control. I do not know if I am in command, or the turbulence is. I think about reducing airspeed to Va so the airplane will somehow continue to hold together in this fearsome pounding. I glance hastily out my side window. Through the dark gray mist streaming by the fuselage lights, I see it. Ice. Ice everywhere! I was distracted by the turbulence. The rocking and rolling, so hellacious a moment ago, has abated somewhat. The airplane is semi-controllable, giving me a chance to concentrate. I check to make sure all de-ice equipment is on. It is. I cycle the wing de-ice boots. Nothing happens. I do not touch the throttles. The airspeed indicator confirms that the weight and aerodynamic drag of the accumulated ice is already slowing me down. The windshield is frozen over. I struggle to believe what I am seeing. The de-ice systems are failing me. I sometimes wondered about a moment like this in a lifetime of flying. Will I think of my family? I could not bear to lose them. Will I panic or will I remain in control of my emotions? I have managed fears in the past. Sitting here now, I can feel my body’s natural response. Adrenaline is coursing through me; blood pressure up; face flushed; heart racing. Short, quick breaths. But I can still think clearly. I make up my mind. Taking some intentionally slow, deep breaths, I banish the desperate and unwelcome thoughts as quickly as they come. I will fly the airplane. I can get out of this. Suddenly, a sharp, metallic banging on either side of the B80’s nose in front of me. What is that? It sounds a little like the sound a seatbelt buckle makes if inadvertently locked outside the door of a small plane, the buckle free to strike crazily against the door in the slipstream. After a moment, I know. It is the prop deice slinging chunks of ice off the blades and against the thin aluminum skin of the airplane. The staccato sound is not rhythmic; it is loud, seemingly random, and a little asymmetric, with the left side taking more of a beating than the right side. It starts, stops, and then starts again. The altimeter is slowly, steadily, unwinding. I am sinking out of my current altitude. Airspeed degrading. 130 knots now. Book stall speed is 80. I push mixtures to full rich, props full forward, and throttles full forward to takeoff power. The fuselage lights are now frozen over so I can no longer see the amount of ice building on the wing leading edges and across the upper surfaces. My feet dance on the rudder pedals, trying to keep the ball centered. Wrestling with the yoke to maintain wings level. Even with full power, I am still descending. Am I going to ride this airplane into the ground? Jagged bolts of lightning now tear the black fabric of the night and light up the amorphous clouds engulfing me. Thunder crashes and reverberates in my ears. Turbulence continues to bat me around relentlessly. Never before have I so much wished to be somewhere - anywhere - else. I continue to battle the controls, but now I think I am losing. I need to turn a few degrees to the left to try to get back on course, but the airplane seems to have a mind of its own. It wants to drift right instead. Sluggish and heavy on the controls. It feels as if I am flying sideways. Airspeed now 110 kts. With the load of ice I am carrying, at what speed does the airplane stop flying? I remain alert for the stall warning horn. At any moment, the alarm could go on – and stay on. I wipe perspiration from my forehead with my shirtsleeve. My mind reels. What happens if the Queen Air stalls and falls out of the sky? At my current rate of descent, I will not have much time or altitude above the terrain to attempt a recovery. A few moments later, I hear a short, loud boom. 12 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame All images courtesy of Dean Zakos

SHORT STORY The aircraft is shaking noticeably. I think, “This is it!” Almost fearing to look, I turn my head to the side windows. The ice, inches thick in places, is slipping off the wings and engine nacelles in large sheets and in little pieces, disappearing into the black void behind me. Chunks of windshield ice are melting away. Then, it is almost all gone. Having descended below the overcast, the air is now clear and smooth. Airspeed and rate of climb increasing. The altimeter reads less than 3,000 feet. I am in control of the airplane again. The lights of the city of Banning are visible to my left, Palm Springs to my right. I have not called a Mayday because I was too busy dealing with the emergency. I radio LA Center and, in as calm and as steady a voice as I can manage, I cancel my IFR flight plan and provide a PIREP on my just concluded ride in the turbulence and ice. I advise them my intention is now to proceed VFR direct Laguna. Visibility under the overcast is excellent. I can see the Salton Sea, with hundreds of lights from residential neighborhoods, observable in the distance. In a few more minutes, El Centro and Yuma appear over the nose of the B80. I make straight in for Runway 06, and land at KLGF. Seeing the runway lights on short final growing larger in the windshield in front of me is a welcome sight. Earlier, during the worst of it, I was not certain I would ever land this airplane under control again. Boxes of processed data reports, securely tied down in the cabin behind me, are turned over to a waiting Lockheed employee. The employee makes no comment to me, although I must look ashen from my bout with the elements. The Queen Air, glistening in the hangar’s light and still dripping in places from the melted ice, is put away for the night, but not before I perform a walkaround. I notice a significant number of small, irregular-shaped dents on the left side of the fuselage, just about in line with the arc of the prop blades. Physical confirmation of my ordeal. I will tell them about the damage in the morning. Now more relaxed, but physically spent, blood pressure and heart rate close to normal again, I am introspective on my drive to the motel. Two big questions: “Why did the de-ice equipment on the Queen Air, about as sophisticated and effec- tive as any available, not perform better on this stormy night?” and “Why did I survive to tell the story?” In response to the former question, I think the technical answer is that the ice I encountered simply overwhelmed the de-ice systems. The rate of accumulation of ice exceeded the ability to shed it. As to the latter question, I cannot provide an answer. I have thought about it often. I wish I knew. Given the known ice certification of the Queen Air and the forecast information I reviewed at the time of my departure from Van Nuys, the intended flight presented a reasonable and manageable level of risk. What I could not know was, on this gloomy and random night, a demon lurked in the clouds. A cold, merciless demon, whose unwelcome embrace has wrecked airplanes and claimed the lives of countless pilots and passengers in the past, and who will do so again in the future. Tonight, the demon stalked me. I enjoyed a wonderful Christmas with my family in 1972. I had much to be thankful for. In the end, the Cheyenne Attack helicopter was not chosen for further development and production. The Army opted instead for the Hughes AH-64 Apache Attack helicopter. I still believe the Cheyenne performed as well or better, and was as capable, as the Apache. But, after all, I am a Lockheed guy. * * * * * [Dean Zakos learned to fly at Batten Field in Racine (KRAC) and at the Westosha airport in Westosha (5K6). Dean was born in Fond du Lac, and currently lives in Madison. He is a member of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), the EAA, and several local chapters of the EAA. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin—Madison, and he has a law degree from Marquette University Law School. His recent book, Laughing with the Wind: Practical Advice and Personal Stories from a General Aviation Pilot (Square Peg Books, 2019), is available at Amazon and at Barnes & Noble.] 13 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2021-2022

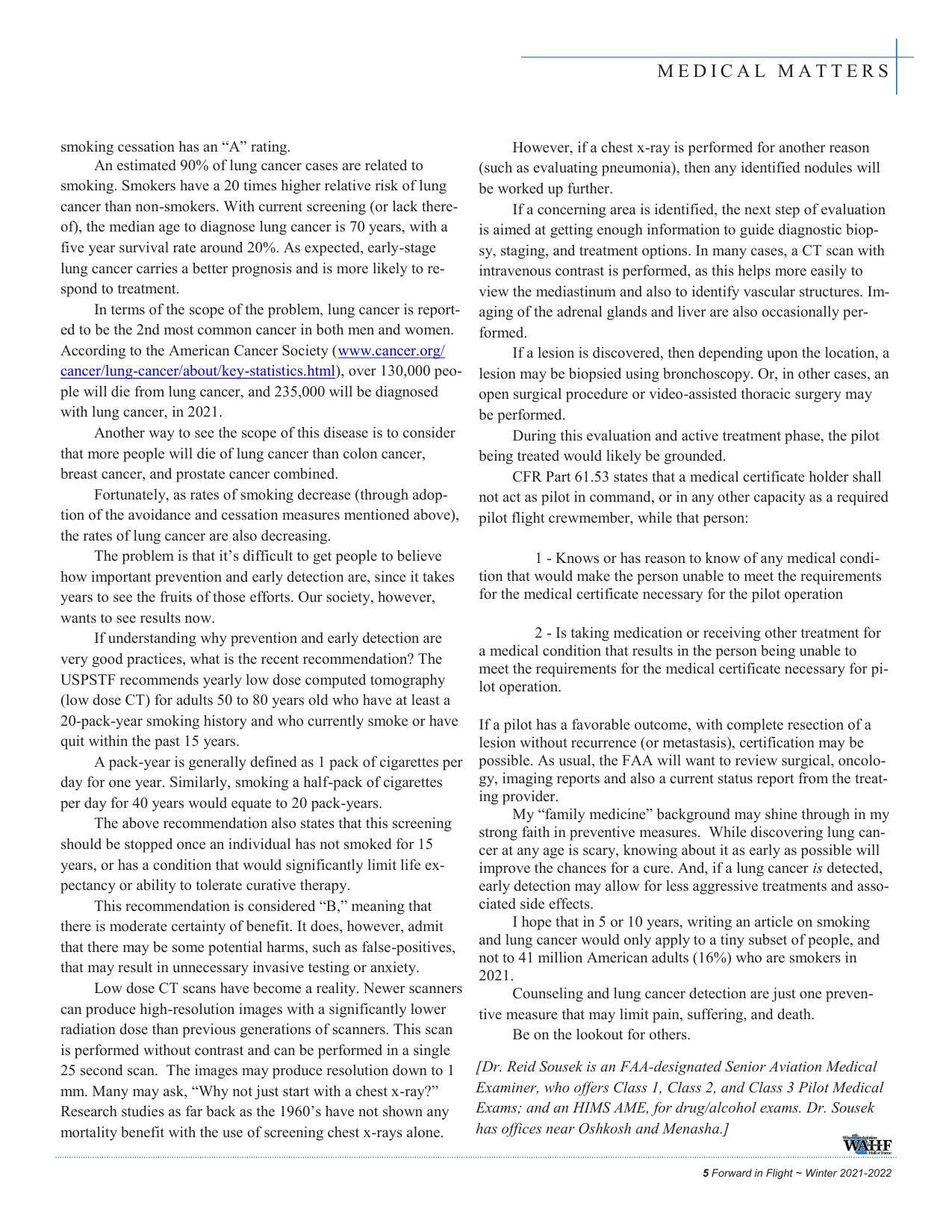

WORLD WAR II The European Air War and Attrition The Mighty Eighth Air Force (1942—1945) By Tom Eisele In World War II, the U.S. Army Air Force, initially in the form of the 8th Air Force, defeated the German Luftwaffe. How did the men of the Mighty 8th (as, eventually, assisted by the Ninth Air Force in England, and the 12th and 15th Air Forces in Italy) effect the destruction of the Luftwaffe? And what aircraft proved to be indispensable? Various “knock-out” punches were tried: the two Schweinfurt raids, for example, in August and then again in October of 1943, aimed against ball-bearing plants; and the Ploesti raid on August 01, 1943. These attempts were failures; in fact, they almost knocked-out the 8th Air Force, rather than the Nazis. No, victory was achieved not through a surprise attack (Pearl Harbor-style), nor an American Blitzkrieg. Instead, it took persistence and patience, commitment and costly battles, again and again, in the crowded skies above western and central Europe. It was not through any one battle, or even one campaign, that the 8th Air Force managed to prevail. Rather, it took a concerted effort through many battles and several campaigns – eventually numbering over 940 separate missions – before the air war was won. The European air war became a war of attrition. It was a matter of wearing the enemy down, doing more damage to them than they did to us, over months and months of desperate struggles. The effort to win took enormous amounts of resources and logistics, and will-power, as well as taking an enormous toll on our men and their machines. Beginnings: The air war in Europe, once the Americans entered the scene in late 1942 and into early 1943, did not start out as a war of attrition. Some in the U.S. Army Air Force believed that long-range precision bombing of the European continent could be successfully accomplished by heavily-gunned four-engine bombers flying in tight formations on their own. “[General Ira] Eaker had always believed in the self-defending capability of the large daylight bomber formation. … The Eighth Fighter Command under Brig. General Frank Hunter shared Eaker’s view that unescorted bomber operations were possible.” [Richard Overy, The Bombing War, p. 359.] The B-24s and B-17s were far better and stronger bombing -platforms than any aircraft the German Luftwaffe had designed or created during its Blitzkrieg rampage through Europe. (LEFT: German HE111 Heinkel twin-engine bombers, as used in the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain; and found inadequate for the bombing campaigns.) 14 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame Still, it turned out that American long-range bombers could not win the war on their own. As noted above, the disastrous twin bombing raids against the ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt – the first raid on August 17, 1943, the second raid on October 14, 1943 – proved decisively that long-range bombers on their own, without heavy and sustained fighter escort, would be decimated by the defending German fighters and flak gunners. The former mission in August was Mission 84 to the cities of Regensburg and Schweinfurt; it cost 60 heavy bombers lost, and a further 75-90 bombers damaged, out of a total of 376 heavy bombers. The latter mission in October, Mission 115, was aptly named “Black Thursday”; it cost the AAF another 60 bombers lost outright. An additional 17 bombers were so badly damaged that they had to be scrapped, and another 121 bombers were damaged but repairable. These casualties in October, 1943, were from a total force of 291 B-17s. (An additional 60 B-24s from the 2nd Air Division aborted due to weather conditions in October, or else were diverted during the mission.) Loss rates hovering between 15-25% of the attacking air forces on individual missions proved prohibitive. Accordingly, long-range bombing missions penetrating deep inside Germany were suspended for the next four to five months. The sad conclusion was that “the Eighth Air Force had for the time being lost air superiority over Germany.” [Cate & Craven, The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. 2, pp. 704-05.] How might the 8th Air Force regain it? They needed more well-trained men, and better aircraft. Recalibrations: Mulling over these hard-earned lessons, the American long-range bombing strategy changed from dramatic raids aimed at achieving a decisive victory in a short period of time, to a more methodical and deliberate attempt to achieve sustained wastage in the German air force and in the German industries supporting the Luftwaffe. Professor Richard Overy summarizes the change in American bombing strategy as follows: In the end the defeat of the German Air Force was an American achievement. [Commanding General] Spaatz divided the campaign into three elements: Operation Argument to undermine the German aircraft production; Photo of a flight of B-24s taking heavy flak during the European air war. (Photo in the public domain.)

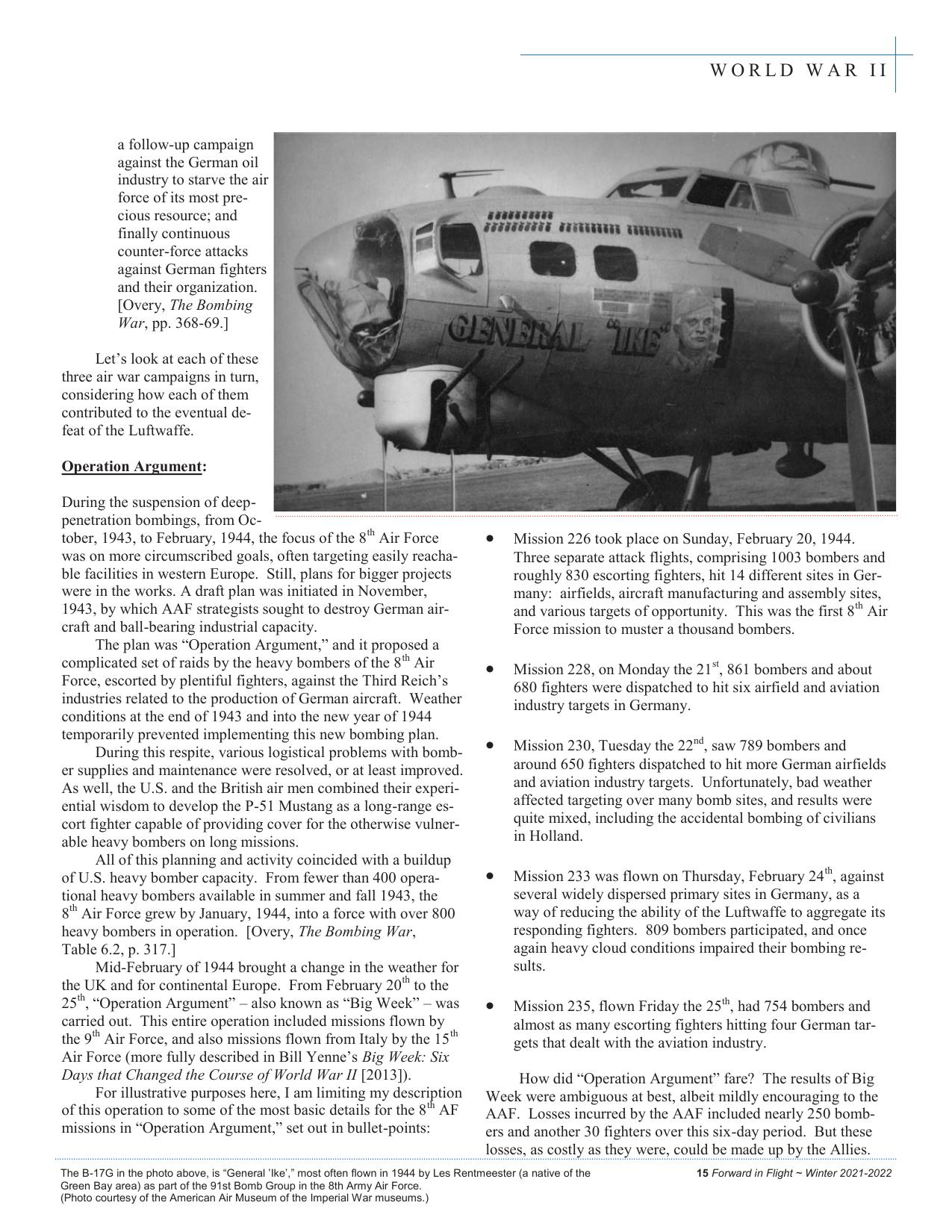

WORLD WAR II a follow-up campaign against the German oil industry to starve the air force of its most precious resource; and finally continuous counter-force attacks against German fighters and their organization. [Overy, The Bombing War, pp. 368-69.] Let’s look at each of these three air war campaigns in turn, considering how each of them contributed to the eventual defeat of the Luftwaffe. Operation Argument: During the suspension of deeppenetration bombings, from October, 1943, to February, 1944, the focus of the 8th Air Force was on more circumscribed goals, often targeting easily reachable facilities in western Europe. Still, plans for bigger projects were in the works. A draft plan was initiated in November, 1943, by which AAF strategists sought to destroy German aircraft and ball-bearing industrial capacity. The plan was “Operation Argument,” and it proposed a complicated set of raids by the heavy bombers of the 8 th Air Force, escorted by plentiful fighters, against the Third Reich’s industries related to the production of German aircraft. Weather conditions at the end of 1943 and into the new year of 1944 temporarily prevented implementing this new bombing plan. During this respite, various logistical problems with bomber supplies and maintenance were resolved, or at least improved. As well, the U.S. and the British air men combined their experiential wisdom to develop the P-51 Mustang as a long-range escort fighter capable of providing cover for the otherwise vulnerable heavy bombers on long missions. All of this planning and activity coincided with a buildup of U.S. heavy bomber capacity. From fewer than 400 operational heavy bombers available in summer and fall 1943, the 8th Air Force grew by January, 1944, into a force with over 800 heavy bombers in operation. [Overy, The Bombing War, Table 6.2, p. 317.] Mid-February of 1944 brought a change in the weather for the UK and for continental Europe. From February 20th to the 25th, “Operation Argument” – also known as “Big Week” – was carried out. This entire operation included missions flown by the 9th Air Force, and also missions flown from Italy by the 15 th Air Force (more fully described in Bill Yenne’s Big Week: Six Days that Changed the Course of World War II [2013]). For illustrative purposes here, I am limiting my description of this operation to some of the most basic details for the 8 th AF missions in “Operation Argument,” set out in bullet-points: • Mission 226 took place on Sunday, February 20, 1944. Three separate attack flights, comprising 1003 bombers and roughly 830 escorting fighters, hit 14 different sites in Germany: airfields, aircraft manufacturing and assembly sites, and various targets of opportunity. This was the first 8 th Air Force mission to muster a thousand bombers. • Mission 228, on Monday the 21st, 861 bombers and about 680 fighters were dispatched to hit six airfield and aviation industry targets in Germany. • Mission 230, Tuesday the 22nd, saw 789 bombers and around 650 fighters dispatched to hit more German airfields and aviation industry targets. Unfortunately, bad weather affected targeting over many bomb sites, and results were quite mixed, including the accidental bombing of civilians in Holland. • Mission 233 was flown on Thursday, February 24 th, against several widely dispersed primary sites in Germany, as a way of reducing the ability of the Luftwaffe to aggregate its responding fighters. 809 bombers participated, and once again heavy cloud conditions impaired their bombing results. • Mission 235, flown Friday the 25th, had 754 bombers and almost as many escorting fighters hitting four German targets that dealt with the aviation industry. How did “Operation Argument” fare? The results of Big Week were ambiguous at best, albeit mildly encouraging to the AAF. Losses incurred by the AAF included nearly 250 bombers and another 30 fighters over this six-day period. But these losses, as costly as they were, could be made up by the Allies. The B-17G in the photo above, is “General ’Ike’,” most often flown in 1944 by Les Rentmeester (a native of the Green Bay area) as part of the 91st Bomb Group in the 8th Army Air Force. (Photo courtesy of the American Air Museum of the Imperial War museums.) 15 Forward in Flight ~ Winter 2021-2022

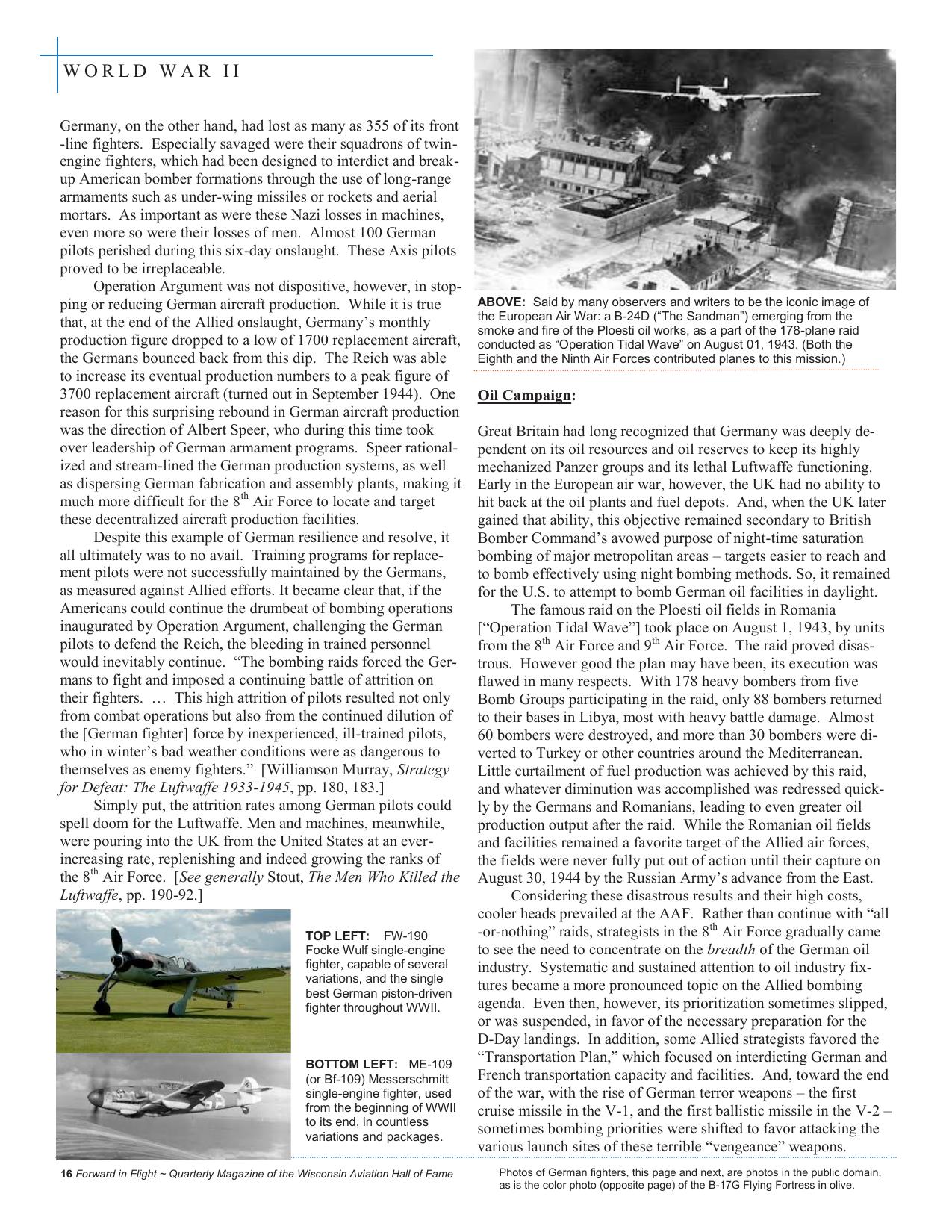

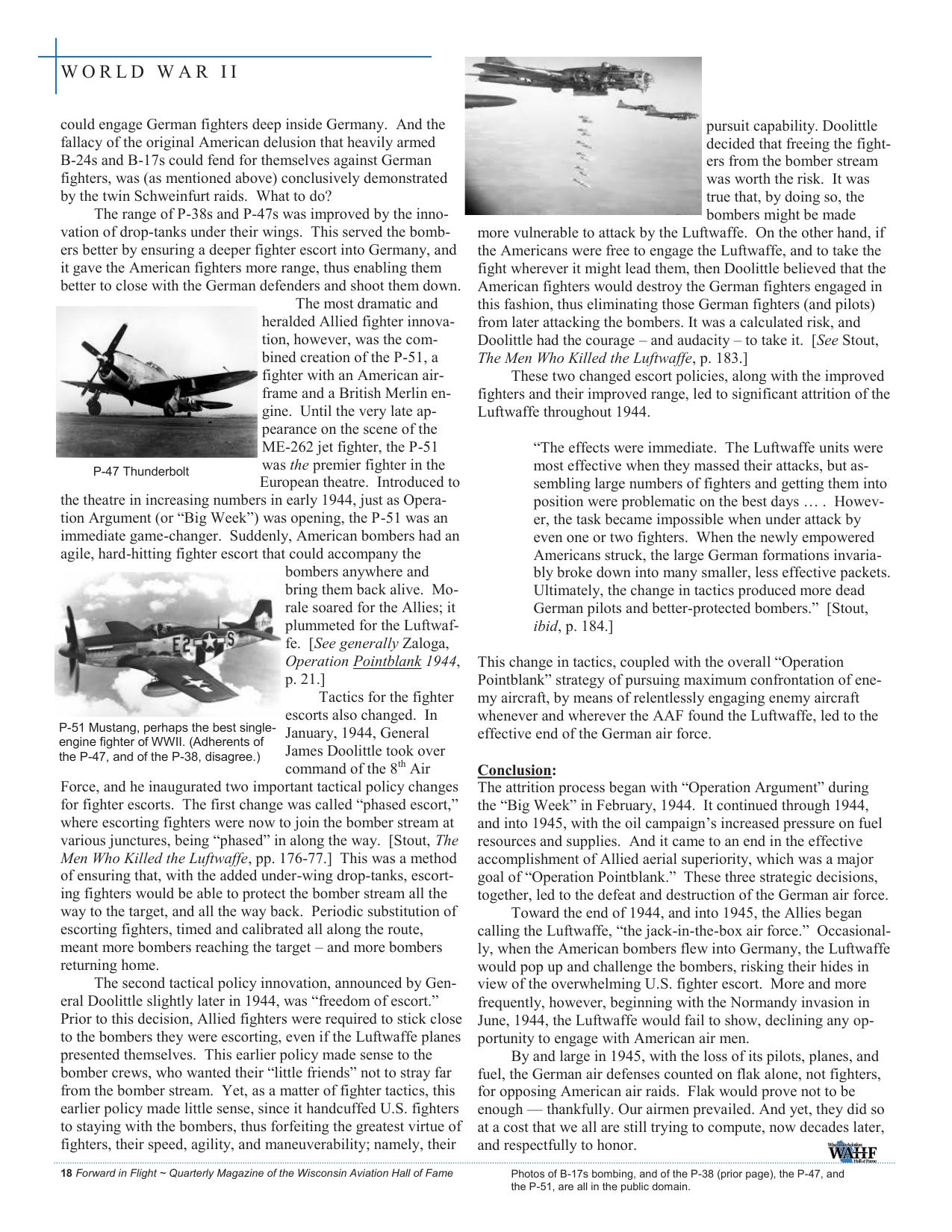

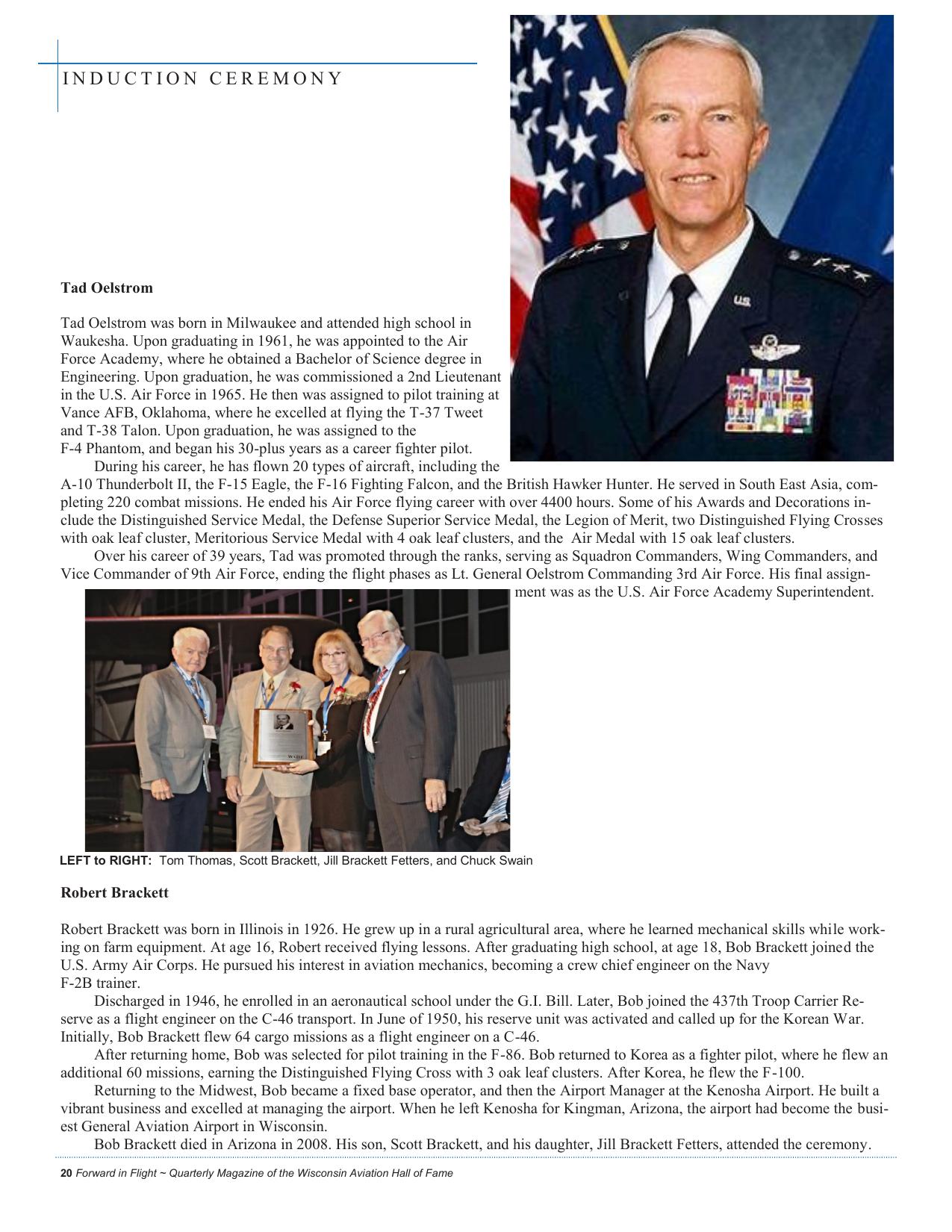

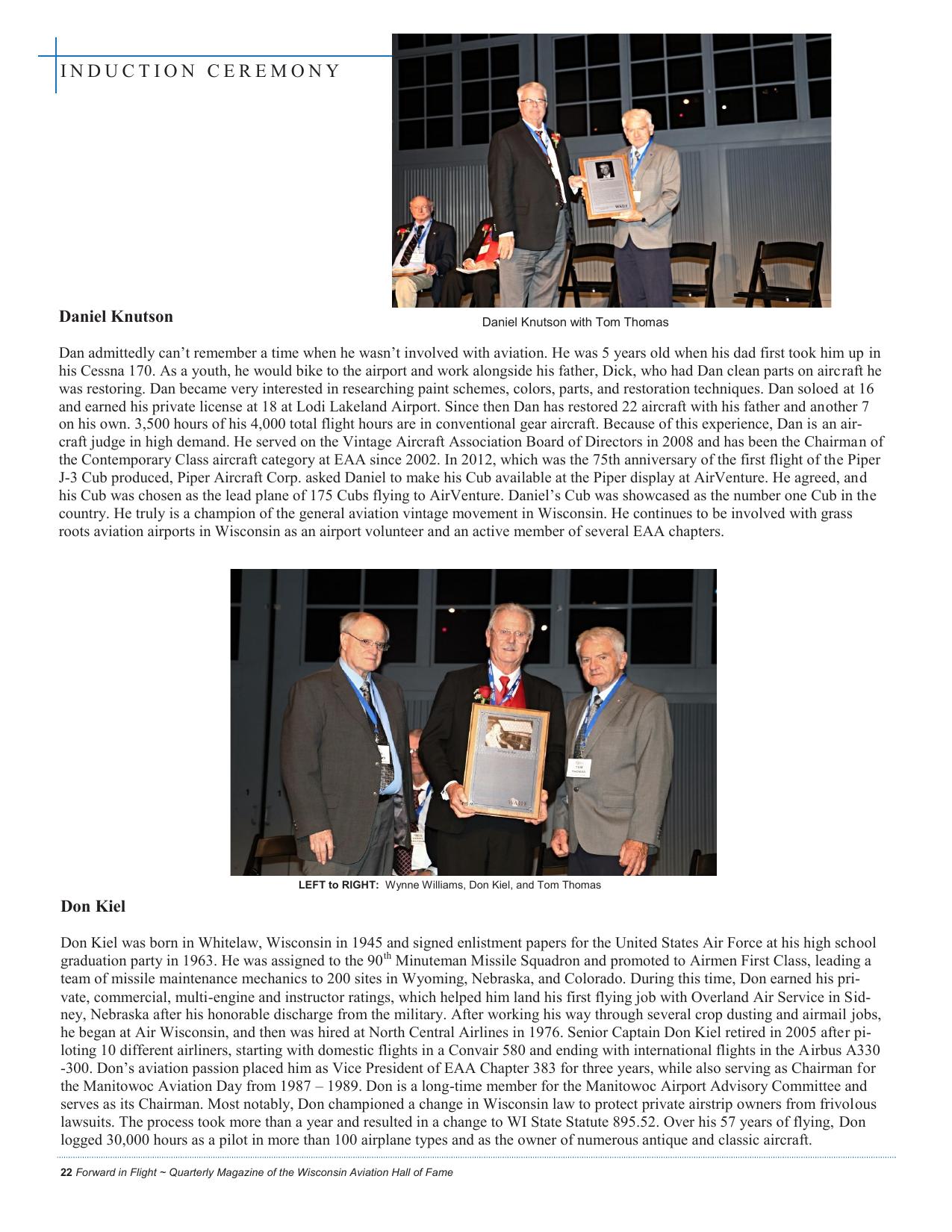

WORLD WAR II Germany, on the other hand, had lost as many as 355 of its front -line fighters. Especially savaged were their squadrons of twinengine fighters, which had been designed to interdict and breakup American bomber formations through the use of long-range armaments such as under-wing missiles or rockets and aerial mortars. As important as were these Nazi losses in machines, even more so were their losses of men. Almost 100 German pilots perished during this six-day onslaught. These Axis pilots proved to be irreplaceable. Operation Argument was not dispositive, however, in stopping or reducing German aircraft production. While it is true that, at the end of the Allied onslaught, Germany’s monthly production figure dropped to a low of 1700 replacement aircraft, the Germans bounced back from this dip. The Reich was able to increase its eventual production numbers to a peak figure of 3700 replacement aircraft (turned out in September 1944). One reason for this surprising rebound in German aircraft production was the direction of Albert Speer, who during this time took over leadership of German armament programs. Speer rationalized and stream-lined the German production systems, as well as dispersing German fabrication and assembly plants, making it much more difficult for the 8th Air Force to locate and target these decentralized aircraft production facilities. Despite this example of German resilience and resolve, it all ultimately was to no avail. Training programs for replacement pilots were not successfully maintained by the Germans, as measured against Allied efforts. It became clear that, if the Americans could continue the drumbeat of bombing operations inaugurated by Operation Argument, challenging the German pilots to defend the Reich, the bleeding in trained personnel would inevitably continue. “The bombing raids forced the Germans to fight and imposed a continuing battle of attrition on their fighters. … This high attrition of pilots resulted not only from combat operations but also from the continued dilution of the [German fighter] force by inexperienced, ill-trained pilots, who in winter’s bad weather conditions were as dangerous to themselves as enemy fighters.” [Williamson Murray, Strategy for Defeat: The Luftwaffe 1933-1945, pp. 180, 183.] Simply put, the attrition rates among German pilots could spell doom for the Luftwaffe. Men and machines, meanwhile, were pouring into the UK from the United States at an everincreasing rate, replenishing and indeed growing the ranks of the 8th Air Force. [See generally Stout, The Men Who Killed the Luftwaffe, pp. 190-92.] TOP LEFT: FW-190 Focke Wulf single-engine fighter, capable of several variations, and the single best German piston-driven fighter throughout WWII. BOTTOM LEFT: ME-109 (or Bf-109) Messerschmitt single-engine fighter, used from the beginning of WWII to its end, in countless variations and packages. 16 Forward in Flight ~ Quarterly Magazine of the Wisconsin Aviation Hall of Fame ABOVE: Said by many observers and writers to be the iconic image of the European Air War: a B-24D (“The Sandman”) emerging from the smoke and fire of the Ploesti oil works, as a part of the 178-plane raid conducted as “Operation Tidal Wave” on August 01, 1943. (Both the Eighth and the Ninth Air Forces contributed planes to this mission.) Oil Campaign: Great Britain had long recognized that Germany was deeply dependent on its oil resources and oil reserves to keep its highly mechanized Panzer groups and its lethal Luftwaffe functioning. Early in the European air war, however, the UK had no ability to hit back at the oil plants and fuel depots. And, when the UK later gained that ability, this objective remained secondary to British Bomber Command’s avowed purpose of night-time saturation bombing of major metropolitan areas – targets easier to reach and to bomb effectively using night bombing methods. So, it remained for the U.S. to attempt to bomb German oil facilities in daylight. The famous raid on the Ploesti oil fields in Romania [“Operation Tidal Wave”] took place on August 1, 1943, by units from the 8th Air Force and 9th Air Force. The raid proved disastrous. However good the plan may have been, its execution was flawed in many respects. With 178 heavy bombers from five Bomb Groups participating in the raid, only 88 bombers returned to their bases in Libya, most with heavy battle damage. Almost 60 bombers were destroyed, and more than 30 bombers were diverted to Turkey or other countries around the Mediterranean. Little curtailment of fuel production was achieved by this raid, and whatever diminution was accomplished was redressed quickly by the Germans and Romanians, leading to even greater oil production output after the raid. While the Romanian oil fields and facilities remained a favorite target of the Allied air forces, the fields were never fully put out of action until their capture on August 30, 1944 by the Russian Army’s advance from the East. Considering these disastrous results and their high costs, cooler heads prevailed at the AAF. Rather than continue with “all -or-nothing” raids, strategists in the 8th Air Force gradually came to see the need to concentrate on the breadth of the German oil industry. Systematic and sustained attention to oil industry fixtures became a more pronounced topic on the Allied bombing agenda. Even then, however, its prioritization sometimes slipped, or was suspended, in favor of the necessary preparation for the D-Day landings. In addition, some Allied strategists favored the “Transportation Plan,” which focused on interdicting German and French transportation capacity and facilities. And, toward the end of the war, with the rise of German terror weapons – the first cruise missile in the V-1, and the first ballistic missile in the V-2 – sometimes bombing priorities were shifted to favor attacking the various launch sites of these terrible “vengeance” weapons. Photos of German fighters, this page and next, are photos in the public domain, as is the color photo (opposite page) of the B-17G Flying Fortress in olive.